VLADIMIR RODZIANKO: I Meet The Ghost Of The Real Rasputin

I first met Vladimir Rodzianko nearly 40 years ago. He lived in a house in Chiswick outside of London, where his father also lived, one of the most famous of Russian Orthodox priests. Father and son had the same name.

The elder Rodzianko had been born Vladimir Rodzianko in the Ukraine in 1915 and he had an amazing study where he did his work, so beloved by many in the Orthodox community. It was a small cubbyhole under the stairs and it was filled from floor to ceiling with icons. Rodzianko, who later went to San Francisco where he became His Grace the Right Reverend Bishop Basil Rodzianko in the Orthodox Church in America, at that time was the most prominent Russian Orthodox leader in England. This was in part because he broadcast religious commentary to his home country during the Cold War on the BBC, and it was probably no coincidence that the junior Vladimir became the Russian voice of the BBC in addition to being a composer of some notoriety.

Poor Vladimir was saddled with me by my mother, the pianist Yaltah Menuhin, who felt that because she had performed his avant garde aleotoric music, had the right to ask him to give me a place to live while I worked on a biography of my family.

My mom was not a fan of most avant garde music, regarding it as pretentious and puerile. She spoke with mild disdain about Rodzianko’s far-out music, which consisted of musical motifs drawn on mobiles which turned in the wind generated through the open windows at the top of the studio. She then was supposed to improvise on each theme, which she did.

Rodzianko the younger felt obligated to my mom because she had played well, and no doubt this feeling of gratitude included not just the quality of her work but the fact that a Menuhin had performed his music.

For her part, my mom found Rodzianko amusing, and described him as writing quite pleasant and competent ballet music at the Royal Ballet School where he was employed. This, of course, was a mild put down, but still affectionate.

I got best of the deal. The house in Chiswick was beautiful and comfortable and Vladimir was great company.

At that point, I was writing about how my grandfather’s father had been killed in Russia in 1905 by a priest holding aloft a cross leading a murderous crowd looking for someone to kill because he had committed the heinous crime of being a Jew. Being able to write in the elder Rodzianko’s study enabled me to create the scene with far more vividness than i would have otherwise.

It was amazing being able to write about that terrible moment in my grandfather’s life surrounded by the study’s crosses and icons in whose name my great grandfather had died.

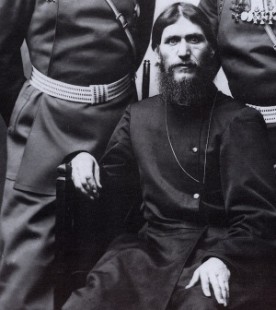

I arrived on the doorsteps in Chiswick baggage in hand and was greeted at the door by Rodzianko the junior who was a tall dark man with a big black beard worthy of Rasputin–whom he definitely looked like. And the looks were not untruthful—he was a kind of Rasputin in more ways than just looks.

Rodzianko was proud of his background. His grandfather was Mikhail Rodzianko, the last President of the Duma just before the Bolsheviks took over. Rodzianko was of a landowning family, a major ally of the Czars, which had put him on Lenin’s hit list.

Even though his family was an enemy of the Bolsheviks, he was treated with a begrudging respect because of the importance of the family’s role in Soviet revolutionary history.

Rodzianko laughed as he told me about his visit to the Soviet Union when he was still the voice that Russians heard over the BBC during the Cold War years. The intrigue was very real. He had had an affair with a beautiful Russian woman. Now he was meeting her for dinner at the hotel he was staying in and some of her “friends” were invited, who were her compatriots in the KGB.

In essence they were blackmailing him, trying to get him to come over to their side. They showed him pictures of his dalliance.

They gave him a certain due because of the exaltedness of his background, but they genuinely wanted him in their employee.

He laughed at them, said Vladimir.

Go ahead, he said. He didn’t care if they told the world. And that was the end of the would-be blackmail.

During the time I lived at Chiswick, Vladimir was constantly getting phone calls. All the papers wanted to interview him after the critics from the biggest London newspapers had given him rave reviews for the music he had written for the Robert Cohan choreographed “Mass,” which was sung by the dancers themselves with multitudinous moans and screams. The work was described as “a general requiem for the victims of man.”

Even Clive Barnes in the New York Times came to write about the “Mass” in London.

“The experiment is that of combining singing (or at least vocal expression) with dancing. During a seven month period, Mr. Cohan worked with the composer Vladimir Rodzianko. The idea was to have the dancers themselves sing a very complicated score while, at the same time, dancing … The technique is complex, with the dancers shouting, sighing, shrieking and singing, while still going through dance movements that really seem to sum up this aural-visual monument to pain and its concomitant compassion. Mr. Cohan’s movements are simple – a walk, a fall, a twist of pain, a gesture to a relentless Heaven. Yet the cumulative effect–and all praise here also to Mr. Rodzianko–is immeasurably moving. It is a theater piece with all the mystery of acknowledged, but only faintly comprehended, passion.”

Rodzianko pontificated on the metaphysics behind the music he had written for the moans and screams of the “Mass” on the front pages of a number of papers and at one point, some of Rodzianko’s overheated commentary got him mentioned in “Pseuds Corner,” a column in the “Private Eye” which made fun of intellectual pretentiousness. He was crushed, for he knew they had caught him dead to rights.

He was smart enough not to believe everything he said. He had told me in all seriousness about how the moans and groans had been inspired by the vision of extermination camp prisoners shouting out their last laments.

And with a straight face, he tried to convince me of another of his triumphs.

Some times very stunning women would show up at his house for “lessons.” Vladimir was teaching them a rather peculiar singing technique. Simply put, he put one hand on the vagina of the woman and the other at the top of her head and then told her to scream as hard as she could.

In those days we were both young men and he and I shared a certain larceny about women. We were both still vigorous and easily got our romantic entanglements too complex to easily handle.

I asked him for help with one such problem. When I left Los Angeles to spend a year in London writing my book, I had been involved with Nigey Lennon, a young woman who was involved with Frank Zappa both musically and otherwise. But I left her behind—I think in part because she didn’t want to go.

In London I met a woman named Vanessa—a Welsh actress who studied at the Central School of Speech and Drama.

But then Nigey said she wanted to come over, she missed me and I missed her. She was due to arrive in a couple of days.

I explained the situation to Vladimir. I liked Vanessa but if I had to make a choice, I’d most definitely go for Nigey.

“Could I bring her over and you take her off my hands?” I asked.

He agreed. And he did. We all got drunk and he made love to her right in front of me, on a couch just a few steps from his father’s study.

Sad to tell, when Nigey arrived a couple of days later, he also wanted to have sex with her. She was insulted, took an instant dislike to Vladimir, and insisted we move out. So we went from living in Rodzianko’s beautiful Chiswick home to an abandoned and impoverished apartment in Notting Hill Gate that my publisher found for me.

I didn’t want him to have her, but I also didn’t want to move. It had been a lot of fun living at Vladimir’s, and I had done some of my best writing ever there.

The other thing about this great Rasputin-like character, he had a certain sadness about him.

For 17 months or so, he had been world famous. The Soviet Union’s most famous ballerina, Natalia Makarova, defected from the Kirov Ballet while in London. At first the newspaper headlines had her defecting because of Rodzianko. Later she said no, she defected because she wanted to perform newer and more contemporary works than she was allowed to do in the Soviet Union. Her arrival in the West was not entirely auspicious. She lost the chance to perform before Queen Elizabeth when she tore a muscle in her thigh.

She also left behind a mother, a stepfather, two husbands as well as devoted colleagues to come live with Rodzianko, who had helped her defect. She was in his arms for nearly two years before she broke off her engagement with Rodzianko, who had become her manager and closest confidant as well as lover.

She began missing her family and friends in the Soviet Union.

She went to Paris to once again partner with Rudolf Nureyev in Swan Lake. They had danced together for many years at the Kirov in Leningrad until he had defected to the west a decade or so before she did.

But the two great Russian dancers had a falling out.

“I don’t want to talk about it…I had an unfortunate experience with him,” she said.

Then she married a multimillionaire husband and moved to San Francisco, leaving behind a broken hearted Vladimir.

I never was too clear from Vladimir’s many and graphic memories of his time with Makarova of the exact gossip of who was doing what to whom. But Rodzianko talked with a certain enthusiasm about Nureyev’s famed collection of cock rings and his myriad of sexual peccadilloes. the rumors of which were mostly true, Rodzianko assured me.

The last time I saw Rodzianko he was still lamenting the loss of the great love of his life. I never regained contact with him, and I’ve noticed that he seems to have disappeared into the woof and warp of London cultural history. He no longer is the toast of the town, or living amidst the headlines.

Still, to me, he will always remain the real Rasputin.