Death in the Desert

Lionel Rolfe

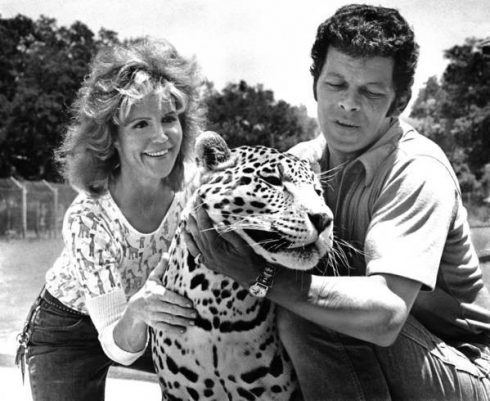

[This piece is from Lionel’s Fat Man on the Left: Four Decades in the Underground (1998). Most of it concerns the shooting death of famous wild animal trainer Ted Derby in Sand Canyon, near Tehachapi on April 14, 1976. Lionel with his then-wife Nigey Lennon covered this story for the Los Angeles Times. Lionel had met Ted Derby and his wife Pat Derby, also a well-known wild animal trainer, when Lionel was working as a reporter for the Newhall Signal, in 1968. In addition to this essay he wrote a long piece about a visit to Pat Derby and her partner Ed Stewart in 2010 at their home in San Andreas, California. The pair had founded the Performing Animal Welfare Society, which operates three sanctuaries for abandoned or abused animals, including elephants, lions, and tigers. Pat died in 2013.]

* * *

When my dog Rosie died, she died an enigma. She was a loyal protector. She saved my wife’s life early one morning when her old car broke down on a darkened side street, and an angry-looking drunk waving a large crescent wrench approached her, muttering angrily. But he stopped when he saw Rosie. Rosie, who was normally a very gentle dog, rose up on her hind legs and growled and carried on so much that the man dropped his wrench and ran. Rosie was a formidable-looking dog, with shepherd, collie and coyote in her. On another occasion, when a large, menacing man drinking from a jug of wine began threatening Nigey and me on a walk up past the Griffith Park Observatory, Rosie saved both of our lives. Again, the man took one look at Rosie and backed off. Rosie had a lot more of the wild beast in her than a domesticated dog normally had. Her genes included not just those bred from wolves centuries before, but those of an active and perhaps dominant coyote.

Rosie had attached herself to us 11 years before in Griffith Park. She was then a pitiful-looking pup, born of a union between a coyote and a domesticated dog, having a tough time surviving in the “wilds” of Griffith Park, which is one of the world’s greatest urban wildernesses.

The familiar, loyal side of Rosie was always very much at home in my bedroom, where she lay at the foot of the bed if she wasn’t allowed in the bed. I had tried to train her not to bother the birds, but it was Nick the African Grey who gave her the best lesson in leaving the avians alone. Nick, also known as the Professor, ran up to Rosie’s tail, angrily and threateningly repeated “Bye bye,” and then gave her a bite on the tail that Rosie never forgot. After that Rosie was pretty scared of these strange feathery creatures that talked like people.

Nick’s dominance over Rosie after that was all psychological bluff and bluster, for Rosie would have been quite capable of devouring Nick in a second had she known her own strength.

As the loyal dog in my Inner Sanctum, Rosie was a domesticated creature. But watching her run the coyote trails in Griffith Park, that was the wild side of her.

Rosie always struck me as being somewhat like Buck in Jack London’s Call of the Wild—a creature only somewhat happy with domestication.

The mix of wild beasts and terrified humans throws a lot of light on the subject of racism.

Racism is just a variation on the vestigial fear some people carry in them for wild animals—for other species. Racism is the same thing except it is directed not by one species against another but against others within the same species—other homo sapiens.

Some similar kind of primeval thing was operating more than two decades ago when Nigey and I were stuck in a Mojave Desert canyon, the earth alive with hallucinogenic patterns of stormy, threatening clouds barely passing by the tops of the foothills enclosing us. First it began raining; then it hailed; and finally as we reached the house we were going to, it had begun snowing.

As we walked into the house, Pat Derby raised her tear-streaked face from her arms and stared dully outside. Then she burst into a wail, a woman suffering the grief of death.

“You don’t know,” she said. “You don’t know how it is. He wrestled all his life with wild animals and he dies at the hands of a man with a gun.”

She was wailing because a human beast had killed her ex-husband, Ted Derby the lion trainer. The people inside that house were Homo sapiens on a mission to save wild animals from the human beast. And nearby Tehachapi was the home to these murderous Homo sapiens.

Derby was a lion in human clothing. He wasn’t a hunter like a lion is, and he wasn’t a murderer like some human beasts. The Derbys understood something about that strange tribalism that brings out the savage in human beasts when confronted with wild animals, however.

The Derbys had divorced but they continued together in their cause, saving wild animals from man’s brutality. When they finally split from a marriage full of sturm and drang over the animals they lived with, they split up their animals Pat Derby remained at their compound in Buellton, over on the coast up north of Santa Barbara, managing pretty well. Ted stumbled until he was invited to move to Sand Canyon on the outskirts of Tehachapi.

Pat Derby’s tears and wails were not just for Ted, but for his collection of wild beasts, including such “stars” as the famous cougars on the Lincoln-Mercury car commercials, and television’s then even more famous “Clarence the Cross-Eyed Lion.” His “trained animals” were much in demand for films and television. But it was always a struggle feeding all the beasts who lived with him, and fending off neighbors who wanted him and his animals out.

People may love seeing wild animals as symbols on television, but confronted with them as neighbors, they became atavistic, and in the case of Ted Derby, so atavistic one of them ended up killing him.

Although Derby was killed by one man, the killer was one among many in the neighborhood who wanted to kill Derby. They knew Derby wasn’t one of them. He was more at home with the wild beasts than with the “civilized” Homo sapiens.

f

There are many Sand Canyons in the Mojave. When a man in the Sand Canyon near Tehachapi offered Derby use of his land back of the Monolith cement works, Derby felt he had no choice but to take it. Would he have thought he had a choice if he had known he would be shot to death by Jack Coyne, a nearby Sand Canyon rancher and member of the board of the Tehachapi Unified School District?

I came on the scene four days after the shooting, called there by people concerned about both the safety of the animals and humans connected with them. I had an assignment from the Los Angeles Times to write about what was happening. The Derby compound in Sand Canyon was crowded with the “family” of Derby supporters. Joe Agapay, Ted Derby’s lawyer and friend, had taken charge. Derby’s son, Teddy, then 14, was there with his mother Pat, Derby’s first wife. Agapay was telling the group the news—that Kern County District Attorney Al Leddy was not going to file charges against Jack Coyne, that he saw no way to dispute Coyne’s claim he had shot in self-defense. Pat Derby could not accept this; she knew Ted. He would never have fired first.

Pat Derby was organizing efforts to take care of the Sand Canyon animals. She heard the lawyer’s report, but could not accept the DA’s decision. “I hate all these people,” she blurted out. “My God, you can’t just kill a man and get away with it. These people were so hateful against the animals, yet they allowed someone to kill a man and walk off scot free.”

Shirley Keith, Derby’s devoted secretary, posed a question: “If the man is out, what are we going to do for protection—how about the girls? They were the only eyewitnesses.” Keith was speaking of Shelley Seaman and Julie Rust, the 19-year-old girls who lived at the compound and were apprentices in animal handling.

“The sheriff won’t give us any protection if the district attorney can find no reason to press charges,” Agapay told her.

Pat Derby looked up. “Where is Coyne?”

“No, no, Pat,” Agapay replied. “California law provides for this. When local officials won’t prosecute, the state’s attorney general can step in. You let me worry about that. You have enough here with the animals.”

Joe Agapay was awaiting word from California Attorney General Evelle J. Younger on his plea for intervention in the Derby case, and he was buoyed in his hopes when the Kern County coroner’s jury held an inquest and unanimously decided Derby had died “at the hands of another by other than accident.” The jury specifically declined to exercise either of its other options—judgments of justifiable homicide or self-defense. Coyne refused to testify at the inquest. But Sandra and Ray Triscari, to whose house Coyne drove right after the shooting, testified. So did Julie Rust and Shelley Seaman and sheriff’s deputies Jim Higgins and Ed Bolt, both of whom had been called to Derby’s place the night of the shooting.

Leddy said he was still studying the inquest transcript, trying to decide whether the jury’s decision and the sheriff’s investigation would cause him to change his opinion not to prosecute Coyne. He kept saying that he hoped to make that decision soon.

Agapay’s letter to Attorney General Younger had put it succinctly. “If it were self-defense, what was Coyne doing on Derby’s property at 12:30 a.m. with a .38-caliber revolver?” Agapay’s letter also demanded that a paraffin test or a nuclear fission test be conducted to determine if Derby had even fired a gun that night. Neither Julie Rust, who witnessed the shooting, nor Shelly Seaman nor Nancy Vigrin, Derby’s fiancee, both of whom say they heard the argument from inside the house, believed Derby fired a shot. Vigrin, who found Derby’s .22-caliber pistol under his body, thought she saw it fall from beneath the bathrobe he was wearing. The last time she saw him through the back window of the bedroom, she said, he had a flashlight in his right hand and a cigarette in his left hand.

Then Younger said that he would leave the matter in the hands of Kern County authorities entirely. Meaning it was all up to Leddy to do nothing, if he so chose.

Ted and Pat Derby met in a San Francisco nightclub in the mid-’60s. She had a revue act; he sang and played drums in a dance band. He was 6 foot 3 and improbably handsome. They were soon married. What drew them together was their love of animals. A farm boy from upstate New York, Derby had been a movie stuntman and had trained dogs and horses for films. But his best break came when he paid $1 for a lion cub that grew up to be “Clarence The Cross-Eyed Lion” in the long-running television series Daktari. Derby taught his wife everything she knew about animal handling, although her fondness for animals dated from her childhood in her native England.

Early in their marriage they quit music and went to work for movie animal trainer Ralph Helfer on the edge of the Mojave Desert. Then they purchased their own place in nearby Placerita Canyon in Newhall. But neighbors’ protests drove them out. These protests—stemming both from fear of the animals and irritation at the noise they made—led the county to rescind permission for them to live there with their animals, and forced the Derbys to move to Buellton, about 150 miles north of Los Angeles.

As time went by, the Derby place became more and more of an animal orphanage, a court of last resort for wild animals who otherwise would have been put to sleep. Most of the animals had tragic histories. Sold as “exotics,” many of the bears, lions, wolves, jaguars, lions, Bengal tigers and falcons had been pitifully mistreated. At one point, the Derbys had about 200 of these animals They tried to support the orphan animals with the “working animals,” the trained ones. But even though the Derbys made good money from the movie industry, the food bill was always more than they made and the wolves at the door were of the human kind—creditors.

The Derbys did not use bullwhips and guns to train their animals. Instead they were practitioners of “affection training,” and as a result Derby’s animals were different. Derby loved to walk into the audience and let people touch and even kiss the animals. Rhoda, the timber wolf, was a favorite with the children. The night before Ted Derby died, he and Pat and Rhoda and her other friends teamed up for a show at the Glendale YWCA; more than 100 children had squealed in delight as they touched and petted the “wild beasts.”

Derby also found favor with many filmmakers because his animals were real actors. His nickname was “one-shot Derby”—the footage rarely had to be reshot. On the other hand, he would not permit any use of the animals that he thought cruel. Among his credits was an animal television special with singer John Denver; he also worked numerous times with Bill Burrud, producer of many television shows on wildlife.

Derby took 30 or so animals to the new place at Sand Canyon after the divorce. A landowner had promised him financial backing for a million-dollar animal compound there, where Derby could run an animal training school open to the public.

But the last year of Derby’s life proved to be his most troubled. His animals required 400 pounds of meat each week and his debts were piling up; he was bankrupt. His promised financial backing fell through and he didn’t have the money to move his animals elsewhere. Meanwhile, the Derby compound in Sand Canyon had become the center of a battle between the canyon’s two big landowners. One gave him a $1 a month lease but part of the leased property was owned by another man not sympathetic to Derby’s cause. What Derby didn’t know was that the fellow who had rented him the land at such a bargain rate was using him to intimidate the adjoining land owner with whom he was warring. The man Derby had signed the lease with was a tough old Kern County landowner with plenty of clout at the county seat in Bakersfield and the capital in Sacramento. The other was a Mafioso type who was later done in by a car bomb in Las Vegas. Derby was caught in the middle of an old-fashioned feud.

And the feud was really only a cover for something far more sinister. Sand Canyon was a claustrophobic canyon, ringed by low-lying barren desert hills that nevertheless gave the feeling of rising high into the sky around the Derby compound. Some of his neighbors may have been involved in a flourishing cocaine trade that used a nearby airstrip for the white stuff coming in from Peru. I learned a lot of the details from a treasury agent who was close to the Derby party of animal lovers.

Other players in the event were some of Derby’s scattered neighbors, who owned compact ranching operations, given over in part to the raising of Arabian racing horses. They began worrying about Derby’s wild animals eating their equines, and what empathy they had had for Derby when he moved into Sand Canyon quickly diminished as news of his financial predicament got around. As they had in Placerita Canyon, residents of the area complained of the 4 a.m. cacophony created by his 30 beasts.

One of those most incensed was Sandra Triscari, who lived less than 500 feet from the compound. She says that she and her friend Jack Coyne, who lived four miles down Sand Canyon, as well as others in the canyon, also suspected Ted Derby of rustling cattle to feed his animals. Rustling cattle was enough reason to kill a man in these parts.

It was to her house that Jack Coyne came at 12:30 a.m. one April evening to say that he had just shot Derby in self-defense. Pat Derby had returned to Buellton after the Glendale show, but on learning that Derby had been shot, immediately made the long trip back to the hospital in Bakersfield.

Derby died about 4:30 a.m. She did not get there in time to say good-bye.

Ironically, the animals were not at the Sand Canyon compound when Derby was shot and killed. The Tehachapi Justice Court, at the urging of Derby’s neighbors, had ordered the animals removed. Derby had earlier been granted some continuances of that order, but ultimately he had to comply with the orders to avoid going to jail. He sold the animals to Robert Schultz, a film industry entrepreneur and a Derby admirer. The transaction was for $1. For the last few days before Derby’s murder, Schultz sheltered the animals in a barn on his secluded ranch just north of Tehachapi, aware that he, like Derby, was in violation of Kern County zoning laws. The animals were to be moved to two permanent sites—the East Bay Zoological Society’s zoo in Oakland’s Knowland Park and some Indian-owned land near Lone Pine. The Indians reportedly were ready to welcome Derby’s animals because they had heard of his gentle ways. Now that Derby was dead, however, neither plan was feasible.

The Knowland Park setup would have been the fulfillment of a lifelong dream for Derby. He wanted a place where people could learn to handle wild animals and he had hoped that filmmakers would come there to learn so that they could produce movies about animals that were more realistic and, more important, not cruel to the animals.

The Sand Canyon compound, situated at the corner of Sand Canyon and Bonanza drives, was a ramshackle place; its 40-year-old structure was the oldest in the usually dry, rocky canyon. Coyne lived four miles down the canyon, near the Monolith off ramp of the major highway linking Mojave and Tehachapi. At the bottom of the canyon, where Coyne lived, there was plenty of wide open space for the 16 head of cattle he kept. But up at the Derby compound, the canyon walls were close together and he and his immediate neighbors were physically closer to one another.

Beyond the Derby compound, on Bonanza, Derby’s closest neighbors, the Findleys, were very opposed to his animals. About 600 feet up Bonanza was the home of Sandra and Ray Triscari. Directly across the road from Derby’s place was Crimson Farms, an Arabian horse breeding operation owned by Tom and Chris Scott. Many of the canyon people were popular musicians who had done well for themselves. One Christmas, for example, Beetle George Harrison had spent three days and nights in the canyon with the Scotts.

The only real canyon original was Coyne, who had worked at the nearby Monolith Cement plant and quarry for 40 years as its chief electrician. It had been 15 years since he had retired, although he still worked on some of its installations.

Later in the day Nigey and I had left the compound and gone into Tehachapi to check the place out. On the lonely road back to the compound, a big cement truck came right up on us and honked and tried to run us off the road. I didn’t get a look at the driver, but later I wondered if it had been Coyne himself who had seen our car among the mourners gathered at the compound.

It was entirely appropriate that something sinister would be connected with that cement plant even today. I don’t know if a cement plant right in the middle of the desert is in itself sinister, but the place had been born in sinister manipulation that would have made it a perfect set for a scene out of the movie “Chinatown.” It had been created at the turn of the century by some of the key figures of the Los Angeles Aqueduct project—General Harrrison Gray Otis, publisher of the Los Angeles Times and William Mulholland.

Monolith was built to sell the concrete with which the aqueduct was built 70 years ago. The cement was of inferior quality, but that didn’t become apparent until many years later. I did a little calculating—this guy Coyne had been working around the cement quarry for a long time. He knew what bodies—literally—were buried where, no doubt. But he hadn’t been around long enough to have been part of the original corruption in which the plant was born. And it did not escape my notice how ironic it was I felt some protection writing about this as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times.

Upon our return to the canyon (we outran the cement truck) we talked with Chris Scott, a tall, English-born former Playboy Bunny who made no attempt to hide her distaste for Derby. “He looked haunted,” she said, “like a hunted man. I felt sorry for him, but I just wanted him to go, to be out of here. He was too polite at those zoning board hearings; he was always so polite and humble he made me feel uneasy. He was a tall, handsome man, so he shouldn’t have been that way. Something was wrong.”

Chris thought of the Derby house as spooky and troubled. Once she had tried to find out if there had ever been a murder there. She said that she was hoping to go in with the Findleys to buy the place and tear down the house and build corrals. She bitterly resented the presence of Derby’s wild animals because she believed they presented a clear threat to her horses. She felt it was hypocritical of others in the neighborhood to take their children to see the animals, then publicly protest Derby’s presence. Chris said that Derby did not take enough safety precautions, that she was constantly afraid one of the animals would get loose and kill her valuable horses.

The night of the shooting she had gone to bed early, so had heard nothing. But she did dream that her car was having a flat tire and suggests this may have been a subconscious registering of the sounds of the shots below.

Sandy Triscari, the unofficial mayor of the Sand Canyon community, had a seemingly charitable view of Ted Derby. “He was very personable, a real gentleman,” she said. “I had originally talked the neighbors out of protesting his plans for a million-dollar animal compound. But when he lost his backing and was broke, and kept getting continuance after continuance to keep from moving out of the house, people came to me and said, `Gee, Sandy, you told us not to protest and look what’s happened now.”‘

Triscari emphasized in her interview with me that she and her neighbors were not animal haters. Indeed, one of the things that got everyone up in arms against Derby, she said, was the time he killed some horses to feed his animals. He had bought them from a veterinarian who was going to put them to sleep. “He came and apologized, but that wasn’t enough,” she said. “My children love horses, and it was a terrible experience. We heard him shoot and heard them dying. I told him I couldn’t accept his apologies.”

Triscari said that while Chris Scott was concerned for her horses, she herself was concerned for the canyon’s children, including her own daughter. The school bus picked up the children in front of the Derby compound each morning, and Coyne had protested at a school board meeting that the situation was potentially dangerous. But Coyne’s real personal concern, said Triscari, was cattle rustling. “Jack lost lots of cattle to rustlers,” she said.

By almost everyone’s account, Coyne’s obsession was rustling and he frequently patrolled the canyon area and drove out those he did not feel belonged there. One rancher, Bud Hansen, who owned several hundred range cattle in the area, complained that about three years earlier Coyne had pulled a rifle on him over a dispute about the ownership of certain cattle. “Later,” said Hansen, “Coyne took shots at me and a guest who was visiting from the East.”

By the time Hansen complained to the sheriff’s deputies, Coyne had already called them with his side. He said he had just been shooting at coyotes. The deputies told Hansen there wasn’t much they could do.

“My visitor packed up and went home. The frontier was too much for him,” Hansen said.

Others told of Coyne bragging how he had caught a couple of rustlers and skinned them alive. Triscari insisted that Coyne was “a real nice guy” but most folks thought he was a mean character, quite capable of doing the things he bragged of.

She showed me a packet of photographs of the neighbors, including Coyne. There were pictures, too, of Beetle George Harrison.

Coyne went into seclusion after the shooting, refusing to make statements to anyone. The sheriff’s investigators had to rely on Ray and Sandra Triscari for Coyne’s version of the shooting. Coyne’s phone was disconnected and Sandra Triscari was unable to convince him to talk to me.

Coyne was first held by sheriff’s investigators on suspicion of murder, but after three days in jail was released by Leddy. Leddy said sheriffs deputies originally told him Julie Rust, who witnessed the shooting, did not see enough to make a good witness. “So really, there were two witnesses, and one is dead. The other said it was self-defense. What do you expect me to do?” Leddy said.

Derby was standing at the edge of his property and Coyne was in his pickup truck on the county road when the shooting occurred, according to sheriffs investigators. They said the men could have been anywhere between eight inches to five feet apart. Shootings are not uncommon in Kern County. In 1975 there had been 53 such murders, and most, said Leddy, were the results of domestic quarrels. He added, “Most end up going to trial.”

Coyne and Derby met twice that fatal night. Soon after the Derby party returned from the Glendale YWCA show, Coyne showed up with sheriff’s deputies Ed Bolt and Mike Whitten. Triscari says she thought she heard “mooing” from the back of the Derby house and called Coyne, thinking it might have been some of his cattle. She says she saw Derby and the girls carrying something into the house in a tarp and thought it might have been a dead cow. But, as it turned out, the “mooing” apparently was only the sounds of the animals still in their cages on Derby’s truck.

It was about 10:30 p.m. Derby invited the deputies to look around his property. But he ordered Coyne off the place, saying in front of a sheriff’s deputy, “You’ve caused me enough trouble.” Julie Rust, who was with Derby, said Coyne was flashing his flashlight into the cages and upsetting the animals. Derby warned Coyne to stay off his property, elsewise he would have to use his gun. The deputies convinced Coyne to leave.

After completing their search, the deputies went to talk with Coyne at the Triscari house. Triscari said they stayed about a half hour and that Coyne then stayed on until past midnight. She recalled telling Coyne as he was leaving, “Be careful going by Derby’s. He’ll be hot—you know, the sheriff’s deputies finding those wild animals on the property means he’ll go to jail for sure. Be careful, Jack.”

“Don’t worry,” Coyne replied. “Derby won’t try anything.” A short while later he was back.

“You’d better call the sheriff,” Triscari said he told her. “I just shot Derby in self-defense.” Triscari said she thought at first he was joking.

Coyne, she said, told her that Derby had come running out of his house and had bounded toward him, waving a flashlight. She said Coyne called out, “I’m Jack Coyne. What do you want?” Coyne told her Derby was shouting a string of profanities and Coyne suddenly realized Derby was holding a gun. According to Triscari, Coyne told her (although he refused to discuss details of the shooting either with sheriff’s deputies or through his lawyer) that he had his .38-caliber pistol to his right on the seat of his white Chevy pickup. When he saw Derby had a gun, Coyne told Triscari an unlikely scenario in which he aimed at Derby’s chest, hoping just to stop him, not to kill him and, on the second shot, aimed for Derby’s face. (The coroner said either shot would have been fatal.) Coyne insisted Derby fired first.

People in the Derby compound told a different version of what happened the morning of April 12, 1976. Around 12:30 a.m. Julie Rust, plagued by bad dreams about dead birds being chopped up and a terrible choking feeling, said she woke up and went to the kitchen for a drink of water. She had been sleeping on the floor in a sleeping bag next to the living room couch on which Shelly Seaman slept. She wanted to sleep nearby because she was scared.

Rust was a shy girl who had been kidnapped as a child. The experience left her wary of people and rather withdrawn, but she was very attached to Derby and the animals, and she was becoming more outgoing. From the kitchen window, she said she saw what she assumed was Coyne’s truck. It was old and white like his truck, she said, although she couldn’t recognize makes of cars. The truck was going very slowly, with its lights off, on the south side of the building, she said.

Rust ran into Derby’s room. She and Vigrin watched Derby searching out back, but then Vigrin, thinking everything was all right, closed the shade. Rust left the bedroom, went out back to meet Derby, and walked down the driveway where she had seen the truck gliding by only a little earlier. “Was it Coyne?” she asked Derby, holding onto the sleeve of his robe.

She said he replied, “It must have been. Maybe he was going up to the Triscari residence because he left something behind.”

Then—according to the testimony of all three women in the house that night—Coyne’s horn honked. They said that Coyne was calling Derby out. Derby ordered Rust to turn on the porch light and get back inside the house. She begged him not to go to Coyne, but when she saw he was going to, she ran back and took a rifle from the gun rack inside the house. Coyne was still in the truck when she got back to the door and she said all she heard was “a smack,” as if Coyne had hit Ted with his fist. Ted jolted and slumped to the ground.

Rust said she told deputies originally she heard only one shot—now, on reflection, maybe two. Derby’s closest neighbors, the Findleys, told deputies they heard three.

Rust said Coyne looked down at Derby from the truck and then at her. “I was still holding the rifle. He just stared at me and then drove away slowly.”

For a while, Janice Seaman, Shelley’s mother, and Shirley Keith were left to care for the animals at Schultz’s Tehachapi ranch. Pat Derby had said she could take some of the animals, but not the bigger ones. She had to return to her place in Buellton because she had her own animals to take care of.

Shelly Seaman was an especially enthusiastic apprentice. I first met her mother Janice through Laura Huxley, widow of the great writer Aldous Huxley. Janice had done volunteer work at the Los Angeles Zoo as a youngster, but watching Derby work with animals was even more exciting. “You’d ask him why the animals did this or that, and he’d say it was because the lion thought you were going to do such and such. He knew what the animals were thinking, and once you sat down and thought about it, you realized he was right.”

I thought of a brief conversation I had had with Cleveland Amory, the writer who headed up the National Fund for Animals and wrote wonderfully funny novels, when I first got to the compound. Amory had called the Derby compound as soon as he heard the news of the shooting. He told me that “when children watched Derby and his animals, they were watching the communication between Ted and animals as much as either the animals or Ted alone. This very ability,” Amory added, “engendered hostility in prejudiced people.”

To Derby’s coterie of animal lovers, Tehachapi was mean country. One of the popular tales around the compound was a conversation overheard between a chef and a waitress in a coffee shop. “Yeah, honey,” the chef said, “we used to shoot niggers and coyotes, but you know, we’re damn near out of coyotes now.”

The three said Derby would not have shot first if he shot at all, and if he had he would not have missed. “He was an excellent shot,” said Vigrin. Also, as the three women tried to comfort Derby while he waited the 45 minutes before the ambulance from Bakersfield and sheriff’s deputies came, he kept repeating, over and over again, as if in astonishment, “He shot me. He shot me.” Shelley Seaman remembered that “not one goddamn person came to investigate or help” during the time he lay there. Sgt. Burt Pumphrey of the sheriff’s homicide detail didn’t find this so surprising, “not out there in the middle of the night.”

Added Pumphrey, who headed up the investigation, “The physical evidence cannot tell you who shot first, and you have to give the defendant the benefit of the doubt. I think the DA is right—he couldn’t have gotten a conviction on the evidence we have.”

Pumphrey added he didn’t order a paraffin or a nuclear fission test because neither test would be conclusive. He was convinced that Derby did fire, though, because his gun chamber had two expended bullets, and there was a bullet dent on the rim of Coyne’s truck door. But no .22-caliber bullets were found on the scene.

Leddy said he had never even heard of Derby until the shooting, despite the fact his deputy in Tehachapi, Gino Spidoni, was prosecuting Derby over the animals

Janice Seaman made sure the animals were kept alive while looking for a home for them. She felt each animal was a very unusual example of its species. She felt there was a lot these animals could teach our species.

As we near the end of the century, the animals who were at the center of the Derby affair are all dead. It’s been enough years that most died of natural causes. Seaman and her colleagues spent their personal fortunes and time to save the animals and keep them together. After being moved from one compound to another, the ones that hadn’t been dispersed for one reason or another finally ended up in the Wildlife Way Station which is now in Little Tujunga Canyon in the Angeles National Forest. The station has been run for more than a quarter of a century as a rescue and refuge for wild and exotic animals. It is a non-profit organization supported by grants, members and tours.

Seaman said that she knows the battle continued in Tehachapi. Some allies of Coyne died mysteriously in a cafe shoot-out—some have suggested that among the animal lovers were some hombres every bit as mean and tough as Coyne and his kind.

She is hazy about the details of all this, admitting she doesn’t want to know any of the details of what happened. She just has private suspicions.

Pat Derby went on with the battle for wild animals—her latest efforts in the ’90s reportedly having to do with protecting elephants in a Northern California town.

My story never made the Times. I wrote it up, and my editor Beverly Beyette and I spent hours going over every word making sure it could all stand up in court if necessary. At first reading the legal department at the paper agreed it was air tight. The story was scheduled to run in the Times and Ted Gunderson, the paper’s top photographer then, went out and took some hauntingly beautiful photographs to accompany it. I went away on a trip to San Francisco. On the day the story was due out, I picked up a copy of the paper but the story wasn’t there.

I put in a long distance call to Beyette. She told me at the last minute the legal department had killed it—not because there were new real doubts but because Evelle Younger, who was by then the state’s attorney general and had a reputation as being entirely beholden to the newspaper, had prevailed upon his many contacts in the legal department not to run it.

She indicated he was protecting people in Kern County who did not want any bad publicity.

The federal agent who had been my source on the story was not surprised that Younger had prevailed on the paper not to run it. He said that Kern County was run like a feudal barony, at the behest of a few of its biggest landowners.

Beyette sounded quite dejected when she told me the story had been killed. Not much later quit her post as editor of the “View” section, although she did go on to write for the paper.

I was scared. Suddenly I felt abandoned. As a writer for the Times, I had felt some protection. But I knew Coyne was a killer, and it wasn’t until a few months later when he died that I felt relief.

The story ultimately appeared in print, and there never were any legal repercussions because it was indeed an airtight story. The story ran with Gunderson’s photos in the old Los Angeles Free Press, which was then edited by Michael Parrish. Parrish went on to work at the Times—first as the editor of the Los Angeles Times magazine and then as a writer in the financial section.

For a while I understand that Truman Capote was interested in the yarn as a result of my story. But Capote died before anything came out of his interest.

Rosie also has died. In her last days we would take her to Griffith Park and one time we watched her bound up the side of a mountain after a full-blooded coyote, perhaps someone she had grown up with there. She ran almost as fast as the coyote but not quite fast enough. For a moment we feared she was going to disappear forever as she bounded over the mountain top after that coyote. But she finally did return, and by the time we got home a violent rain was lashing the windows of our home and Rosie was all settled in at the bottom of our bed.

I remember looking at Rosie, and then at Nick the African Grey. We have a curious relationship with our animals who are not quite wild and not quite domesticated. It’s not the same relationship we have with “pets.” They are not quite pets, but if we take them from the wild, they “need” us.

We need them as well.

Here is Lionel’s essay on the death of Pat Derby in 2013.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.