Unlocking The Secrets Of That Incredible Flameneco Music

Conde, rehearsing with mezzo Soprano Kindra Scharich

By LIONEL ROLFE

When I was not yet quite a teenager, I spent a few years studying the classical guitar under Dorothy De Goede. She was a strikingly beautiful woman who had been a student of Andre Segovia. I was, of course, in love with her even though I was barely a decade old. I then wanted to study flamenco, so my parents sent me to Carlos Montoya. I loved flamenco but Montoya’s best and most patient coaxing did not teach me how to unfurl my right hand with that particular flamenco sweep. I should have had some genetic disposition. My dad was half German-Jewish and the other half Portuguese-Jewish. His mother grew up speaking Ladino in Seattle. The few remaining Ladino speakers lived in Seattle at that time–La dino is a combination of Hebrew and Spanish.

Yiddish is Hebrew and German. Appropriately my father, a scholarly judge by profession, loved the classical guitar, an instrument whose popularity really began with Segovia. The guitar, like a piano, can be a whole orchestra. My father also loved lutes, and we regularly went to the lute club. My dad loved to play the guitar in his heavily wooded paneled study where he also smoked his fine cigars. Maybe that was the Iberian in him, and I got a bit of it too, by osmosis if not genetics. In retirement, my dad spent a lot of time in Spain and Portugal, acquiring more guitars.

SISTER AND BROTHER CROON

My dad had been gone for several years when I was contacted by Doranne Croon Cedillo, and she told me her brother Drew Croon had written a “Gypsy Mass” before he died in 2007–he was born in 1951. She was mounting two performances–one in San Francisco and another in Beverly Hills. I was instantly intrigued. Cedilla said that rarely had anyone written a piece of serious classical music based on flamenco. I knew that the great Spanish composers–Rodrigo and de Falla, among many others, borrowed a lot of flamenco melodies and rhythms, but used them only as embellishments. Would I like to write about it? Of course I would.  Flamenco’s roots are mysterious–they comes from the Andalusian region of Spain, and were created when the area was part of the crumbling empire of the Moors–an Arab and African people–who ran the south of Spain. The Romani tribes were from India, and had lived as slaves in the Persian empire. Who knows how the two people interacted, but in one way it is known–they call it flamenco. Prominent among the non-Christian outcasts were the Jews.

Flamenco’s roots are mysterious–they comes from the Andalusian region of Spain, and were created when the area was part of the crumbling empire of the Moors–an Arab and African people–who ran the south of Spain. The Romani tribes were from India, and had lived as slaves in the Persian empire. Who knows how the two people interacted, but in one way it is known–they call it flamenco. Prominent among the non-Christian outcasts were the Jews.

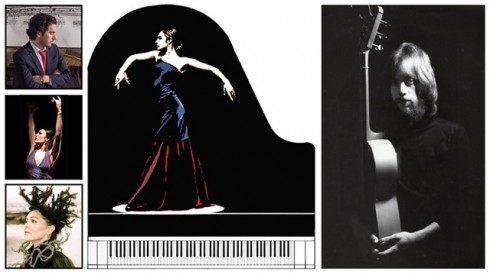

At the heart of the ensemble Doranne assembled was Alex Conde, the classically trained pianist from Spain. His father, Alejandro Conde, played Flamenco guitar and sang and in the last decade Alex has spent in the United Staes, he has found his passion returning in the form of Flamenco. He has found a good Flamenco base in Baghdad by the Bay. And, he says with a laugh, the climate suits him better than was the case in Boston. He says you have to understand that the Spanish monarchs and Catholic clergy were incredibly harsh on the people of Andalusia.

“The music is all about the bad things that happened to them,” he says. Particularly despised were the Romani and Jews and the black Moors who were often Muslim. Alex notes that the great irony is that many of the Romani today are members of evangelical Catholic cults, and rarely play their wonderful music in public. They “believe in God and pray all the time.” He said they are closely knit, and patriarchal. There are many rules for women. The men tend to have the last word. They are very conservative.” But the music isn’t “conservative.”

Quite the contrary, which is what gives it an enduring appeal. Flamenco is defiantly improvisational; like many great musical traditions such as blues it is music that comes out of suffering and survival, love and death. Conde does not apologize for playing Drew Croon’s Gypsy Mass, even if flamenco purists would object. Just, in fact, as they reject the very notion of a flamenco mass that uses a piano instead of a guitar. But he likes Drew’s music for the way it mixes the sacred and the profane, which he thinks is particularly attractive and beautiful. Conde is fairly much traditional Spanish by background. His father is from Valencia on the Mediterranean coast, which has Moorish roots, and his mother is from La Mancha–he notes with a smile La Mancha is the same place where Cervantes came from.

He grants that it is at least an irony that the words of this “serious” piece of flamenco composition are in Latin–but the music is authentically Flamenco–both in terms of melody and rhythm. Yes, the texts are sung in Latin and are very traditionally Catholic, and the result “is a beautiful mix in my opinion.” Conde was trained as a classical pianist, but when he came to the United States to pursue his classical studies, he began to miss flamenco tremendously. Perhaps it was a form of homesickness, he confesses. He’s aware that there is no central flamenco hierarchy. But many believe you can’t play flamenco unless you’re Gypsy, he says. Some would consider a Latin Mass “a kind of traitorous thing.”

Others will be angry because he’s playing on a piano instead of a guitar. Yet the essential purpose of the modern guitar was to be kind of a replacement for the piano. In any event, Doranne was lucky to have found Conde. He was a good match for Croon. Croon was not Spanish. Doranne says their parents were mainly Swedish and Irish. Croon’s grandfather came from Sweden and Croon is a Swedish soldier’s name and his mother was a McCabe from Ireland. “I’m not sure how my brother came to love Flamenco guitar so much. It was a natural progression. Maybe it was a natural progression for him. When he was 18 he gave up electric guitar to play classical and was drawn to Spanish classical particularly. He was fascinated by and appreciated greatly the Spanish, French and Italian cultures in Europe, the cultures and languages of Latin derivation.

He grew up in the Atwater section of Los Angeles before moving to France. Even then he sought out a Flamenco guitar. He ate, drank and breathed flamenco guitar studies eight to ten hours of practice a day–at the same time he was teaching all finger-picking styles at Charles Music in Glendale. When he turned 21, his teacher told him he had nothing more to teach him. Then he started traveling to Spain where he studied with flamenco masters there. When he lived in France, he rode his bicycle from France throughout Spain many summers, spending more time there when he could.” For herself, Doranne Cedillo makes it clear she loves his music, and wants the world to hear it. Thus I attended the premiere of “Misa Gitana Andaluza — A Gypsy Mass” from which scores of people had to be turned away at the Poppy Art House in San Francisco’s Mission District on March 22.

Kindra Scharich

There in this wonderfully San Francisco-decorated store, once we were seated, my eyes were instantly riveted on Kindra Scharich, the moment the opera singer opened her mouth. Her voice was so full and complex and warm. I can’t quite describe why, but the voice seemed roomy and resonant as if I were sitting there with a great view of the all the sounds of the universe–in which all the cacophony had been banished. She had an angelic face, dark enough that it easily could have been Spanish, but later she explained to me that she’s not. She’s German, in fact German with a lot of Jewish in her.

Later when we talked about that, I observed that her “German” family might have come from the Spanish Expulsion of 1492. She said her background included being from a German Village in Russia. Her father who was a chemist, and not particularly religious when he came to Midlands, Michigan, to work for Dow Chemical after the war. She also has Scottish blood by way of her mother. I wondered if her voice would be so beautiful if her face wasn’t so beautiful. It was kind of an idle thought, perhaps without much real point–yet her unique voice and beauty were plain for everyone to see. Kindra says that she’s not quite sure how she was chosen to join the ensemble–Doranne first contacted her, possibly at Conde’s strong suggestion. She knew Conde and Fanny Ara, the dancer, had worked together. She knew of Ara, but had not worked with her.

Now that she is, she says it’s “like playing chamber music,” and for most musicians that’s a very good thing. Chamber music generally provides the most satisfaction to the musicians involved. The intimate synergy gets the musicians closer to the source of the music. “One of the things that was really challenging is that we didn’t know Drew. We couldn’t be sure of Drew’s absolute intentions.” So Doranne allowed the musicians to be flexible and fluid enough to recreate those intentions in their own way. Kindra says that she understands when a person is in charge of bringing a loved one’s music to life, one has to do so carefully. And she adds, “At so many points it would have been nice to have Drew there.”

She suspects that she was chosen in part because “it’s notated and they needed someone who was classically trained.” And she’s classically trained. She also understands that he was melding many things, all a reflection of Croon himself who obviously wanted to create a Latin mass with Flamenco music. She explains that the words of the masses “are meaningful to her” even if they don’t express her personal belief. As she sees her role, it’s not to express one’s personal beliefs, but to take on the attributes of a particular expression.” Kindra says that Croon did an incredible job of “matching the world of the dance to the spirit of the texts.” If he had a particularly energetic text, he chose a very energetic dance. If the text was more reflective, he chose a more subdued dance. “Flamenco comes in many different styles–from vibrant to slow and ponderous to reverential,” she says–and Drew put them together well.

Fanny Ara

Next I talked with Fanny Ara, the Flamenco dancer who with her castanets was certainly the visual show stopper. Here you have the pianist and singer mostly following a score, whereas the dancer’s every move is not notated. For her, Ara told me, dancing is not an intellectual exercise–it’s about what she’s feeling. It’s the feelings she wants to communicate. That’s why she didn’t want to rehearse a lot–she wanted to keep that improvisational door fresh and open. Ara is Basque, but from France, not Spain. She admitted to even feeling more French than Basque. Like Conde, she studied piano, ballet and modern dance, but kept returning to Flamenco. She went to Spain to study Flamenco. To Ara, flamenco is heavy, about earth emotions, a heavy art form whereas Croon’s work is “airy, like you’re flying.” And, she said, that’s where the magic comes from. “I took the liberty to put more Flamenco into it,” she says. She said she asked to take some liberties, and was given that permission. She said she and Conde made the changes she had written. They then rehearsed them to see how it worked out. She says with satisfaction it worked well. I think my dad would have thought so too. * Lionel Rolfe is the author of a number of books, most of which are available on Amazon’s Kindle. Many are also available in paperback.

And here from YouTube is

Drew Croon’s Misa Gitana Andaluza – A Flamenco Mass

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.