Tosi’s Novel “Our Own Kind” Continues With “The Prophet Of Spring Street”

By Umberto Tosi

By Umberto Tosi

(Copyright © 2014 by Umberto Tosi, all rights reserved.)

—————

Umberto Tosi‘s latest novel is Ophelia Rising, a literary historical novel about Shakespeare’s fair maiden before and after Hamlet.

7. THE PROPHET OF SPRING STREET

Here he comes, the prophet of doom. His bombast echoes off the bland glass and concrete of civic center. Shambling forward, hollering Gospel, as he hears it in his head, he parts lunch-hour pedestrians like the Red Sea. Every damn day. His booming could crack tree trunks:

“HELL! You’re all gonna go to H-E-L-L-! Hell! Hell! You’re goin’ to H-E-L-L-!”

Over and over, louder and louder until he arrives like a bad squall, spiral-eyed, tall and gaunt, with long blondish hair and beard bristling. He always wears a plus-size, cream brassiere like a helmet, D-cups akimbo like Viking horns, with the straps dangling, as he strides forward as if into a stiff wind, to the syncopated cadence of his remorseless chant:

“Ha-hell, ha-hell. You’re all goin’ to ha-hell, damn-a-nation and-a h-hell. You’re all-a-gonna-go-ta h-e-l-l-l-l!”

He’s a standing joke at the first-floor magazine office, where they can hear him bunkered from his midday, holy barrage inside the massive gray walls the old Times building. On this particular day, however, the hellfire rant stops suddenly. Down on the first floor, Benny sees Preacher Man’s face flush to the pane nearest his and Makeda’s desks. Preacher Man cups his hands against the glass and peers at them with Apocalypse eyes. His face floats disembodied against the dark glass like Jesus on the Shroud of Turin. His lips move soundlessly.

Makeda drops a No. 2 pencil on her proofs. “Jesus … It’s him!”

Ben laughs. Thinks she’s joking. “Could be. He returns.”

She stands, glares at the man, grabs her purse and strides from the office.

“Where you going?” Ben follows down the hall into the gray-green Vermont marble foyer in time to glimpse her exiting the massive brass doors to the street. “What the hell?” He catches up to her on Spring Street, about a block south of the Times. Preacher Man is well up ahead, ranting hellfire again.

“Hey, Makeda. What’s happening?”

She keeps walking. Preacher man rounds a corner up ahead. He’s nowhere to be seen when they reach the intersection.

“Sonuvabitch must have hopped a bus.”

“I don’t think one runs on this street. He’ll be back. What do you want with him anyway?”

“Need to talk to that motherfucker.”

“Shouldn’t be too hard to find. Beat cops probably know where he goes. I heard he hangs at this cult church sometimes – Orchard, I think.”

Makeda keeps walking, eyes ahead.

Ben steps lively to keep up. “Hey. Want to get lunch?”

She slows. “Later, Ben.”

“Well. Okay. Guess I’ll get back.”

She keeps walking.

“Unless you need me. I’ll go by the sandwich stand. Want me to pick up one for you?”

“No. Thanks, Ben. I’m cool. I want to walk a little.”

“Okay. See ya, then.”

She doesn’t return to the office until late afternoon. It’s unusually quiet. Ben stands at his desk, phone in hand, pale. He puts down the receiver and looks at her, his eyes vacant.

She interrupts him when he starts to say something. “I know, Ben.”

“You heard?”

“I was in a store. It was on the TV.”

“Sniper. Fuck! Those fucking bastards.”

“Gonna be hell now. Preacher Man was right. We’re all gonna to go to hell, all right.”

“I think we ought to go, make sure the kids are okay.”

“Nothing we can do here until tomorrow. Everybody’s on the daily is working on this. By tomorrow we’ll be redoing the weekend editions too.

Public tragedy. Again. Biggest story since JFK in Dallas, and all Ben can do is get home at watch it on TV like anybody else at this moment, far from what he had assumed would be life on a big paper. I’m a paper journalist all right, ass in swivel chair, not out there checking sources, getting the inside stuff, banging out the big story on deadline, dwelling in a Walter Burns, black-and-white Hollywood fantasy.

Ben drives Makeda to his place, like on most other weekdays, where she would pick up Keesha and take her own car home.

Ben drives Makeda to his place, like on most other weekdays, where she would pick up Keesha and take her own car home.

Moving slowly in traffic, they heard details on the car radio. “It is confirmed now. Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr., pronounced dead at Mercy Hospital in Memphis, the time 7:05 pm central, from a single shot to the head. His killer or killers still at large according to a Memphis police spokesman…”

Ben grips the steering wheel. “Fuck, fuck, fuck!” Ben flicks on the air conditioning. They’re stuck in the usual, Hollywood Freeway commuter jam. People are honking. He feels the heat and anger rising. He wonders how many people in the cars around them have guns.

“Are you surprised? Why would you be surprised?” Makeda bums a cigarette from him and punches the dashboard lighter. He’s never seen her smoke.

“It was bound to happen. And the icing was when he went from civil rights to economic justice, Vietnam and peace, it figures they were going to put an end to him.”

“Yeah. How are the going to keep their war going without the brothers?”

“Bottom line. He was threatening profits now.”

“And God forbid, fat old white men who start wars might have to send their own sons to ‘Nam.”

“You realize we’re finishing each others’ sentences, Makeda?”

She had to laugh, at least for a moment. “Shit, Ben. Don’t know if I’m ready for that.”

They fall silent, listening to the reports. Riots have already erupted in major cities. So much left unsaid.

When Makeda and Ben arrive, Linda and Nicole sit on the floor with Keesha drawing on a big strip of off-white butcher paper using colored pencils and crayons. They wave hello. Zoya makes a smile with her wide-spaced, knowing Russian eyes, red with grief, not just onions. Her deep-fried pirozkis waft heavenly comfort as they have through other tragedies for centuries.

When Makeda and Ben arrive, Linda and Nicole sit on the floor with Keesha drawing on a big strip of off-white butcher paper using colored pencils and crayons. They wave hello. Zoya makes a smile with her wide-spaced, knowing Russian eyes, red with grief, not just onions. Her deep-fried pirozkis waft heavenly comfort as they have through other tragedies for centuries.

Zoya is the refugee Russian woman Benny hired to take care of the kids and keep house through the Jewish community center. A few months ago this expanded to include babysitting Keesha.

Little Nicole loves Zoya. Nicole loves everyone. Linda showed her preadolescent disdain at first, giving way to grudging warmth. Zoya had been a teacher in Minsk.

“Look, Daddy.” Linda points to Cyrillic letters she’s crayoned in nut brown on the butcher paper, Я люблю шоколад. “It means ‘I love chocolate.’ Very subversive.”

The TV is off. Ben turns it back on, sound low, just to check the news about King. It’s not good. The kids complain about no cartoons, but without energy. They go back to drawing, then they a play a bit of hide and seek.

Keesha runs to Makeda. “Can we sleep over, mommy, please?”

Ben interjects softly. “Maybe it’s a good idea. All hell is breaking loose out there. You and Keesha take my bedroom. I can sleep on the couch.”

Makeda looks at Keesha. “We’ll be all right.”

Linda and Nicole join in. All three run around the adults, Linda smirks at making the adults uncomfortable. “Sleep over, sleep over!”

“Shh. Be quiet kids.” Ben glances at Zoya then back to Makeda. “Let’s have the food Zoya was nice enough to fix, and check the news.”

“There ees plenty for efferyvone,” Zoya gives Makeda a motherly look and steps into the kitchenette as if to demonstrate.

“You stay too, Zoya please, and I can drop you home afterward.” Zoya’s small apartment is just down at the base of the canyon road in Hollywood. On most evenings, Makeda would have dropped her off on her way home with Keesha, another half-hour away, near La Brea and Crenshaw.

Makeda picks up Keesha and bounces her gently on one arm. “I’m not very hungry, but lets eat, and I’ll think about it.”

Keesha shouts. “I want pancakes for breakfast!”

Linda smirks again. “With whipped cream and strawberries.”

The comforts of domestic routine keep horror at bay for the moment. Ben drops off Zoya after dinner, then cleans up while Makeda gets the kids to bed and reads them a story in the girls’ bedroom. Keesha and Nicole nod off together in one of the twin beds. Makeda tiptoes out and has the TV on low when Ben returns. “Looks bad.”

Ben eyes the flashing news feeds. He sits cross-legged on the floor against the couch on the opposite end from her. “The fire this time…”

Makeda pats the couch pillow. “I need to be held right now, Benny.” He gets up and slides next to her, a friendly arm around her shoulders.

A somber David Brinkley chronicles “burning and rioting in cities across the country.”

8. YOUR OWN KIND

When Ben was in grade school, his parents would take him on a sleeper train cross country for summer reunions with family in New York and Boston. He would run back and forth through the passenger cars with other kids all the way from the baggage car to the observations car at the back of the train. These were the long, twenty-plus-car trains of the 1940s, when rail travel was primary.

He remembers seeing lots of black people riding in some of the coach cars, but none in first class compartment cars where they rode. He asked his mother about that. “Oh, they like to be with their own kind,” she had responded, all smiles.

“What about the porters?”

“They like being porters.”

Seemed to make sense. Porters were always cheerful. He didn’t ask about the conductors, who were white and always grumpy. Adults had their strange ways, and questions never brought answer that made much sense – like his father’s theory of why Joe Lewis and Sugar Ray Robinson beat all comers in the ring.

“Black men have thicker foreheads, just enough so they can take a punch better than whites.”

“Does that crowd their brains, dad?”

“Not at all, Benny, it’s just better armor.”

He grew up amid urban whites – Jews, Italians, Irish, Polish. They all had a little bit of color that Benny could have used, but he didn’t think of it that way. He was simply himself at home. His parents never mentioned his paleness, and he didn’t remember the many diagnostic visits to clinics when he was very young.

All the fuss at school came as a surprise, Nothing happened in kindergarten. Not until second or third grade did the taunts start. His parent moved a lot, and he always arrived as the new kid anyway – fair game.

He shed beliefs and assumptions like a molting lizard as he grew up, major and minor ones – that masturbation would send him to hell as well as grow hair on his palm, for example – beliefs tried, attitudes morphing as he read books – and newspaper stories, and their headlines that fascinated him, then TV news, pictures in Life Magazine. He learned very little through life experience until college and the circles through which he traveled now.

His most piquant discovery of late: Those most excluded had most to say. Hell could forge art, comedy, literature. What doesn’t kill us makes us funnier. At the same time, being an American in spite of himself, he believed in the pursuit of happiness by the shortest route possible, setting no store in suffering.

Such speculation conferred no special skills on him, and caused inconvenient abandonment of cheap biases and heuristics – as much as this is possible for any human being. He didn’t think much on the notion of “sticking to your own kind,” that people kept mouthing, except to wonder: Just who the hell are “my kind,” white-mushroom people, ghosts, freaks, all of the above?

He heard his aunt Lala, on his father’s side, say to a friend over the phone that “the Jews all stick together.” Did that mean his mama’s own kind would be the Steins of Brookline, Massachusetts? Why did she let them name him Beniamino, after Gigli, with whom his nonna, Renata, had sung back in Italy, Benito Mussolini’s favorite tenor, a fact seemingly forgotten among Italians that Benny knew growing up. No wonder his parents didn’t stay together. Moving to Hollywood, spared his father the embarrassment of a Jewish – and, worse yet, a chalky albino son.

It is kiss-tomary to cuss the bride. Benny’s mother made him a list of famous albinos in history from eleventh-century King Edward the Confessor on. Bores, all failing to inspire Benny, except for William Archibald Spooner, dotty, nineteenth century Oxford dean of peculiar speech habits. Like Benny, Dr. Spooner didn’t suffer usual ocular disorders badly enough to hold him back from academic achievement. Constantly, Ben’s mother admonished him never to feel sorry for himself – to thank God for being able to read, though with thick glasses and otherwise see just well enough – with glasses – to get his driver’s license as a teen.

Mama emphasized the Spooner scholarship and didn’t mention the crossed wires that won the dotty dean a place in the language. Perhaps, thought Ben, the professor was not speech-impaired at all, but flipped syllables to keep his mocking classroom buggers alert so they wouldn’t “taste the whole worm.”

Adults tried not to be annoyed by Benny’s habitual spoonerisms. I like butter on my cop porn. That put him with a speech therapist for a while. Miss Marney, a buxomly delicious, laughing, brown lady, just out of college herself, in rainbow beads and bracelets, leaning forward as she coached him.

Benny keeps a picture of dean Spooner, or seen dooner, wrinkled, torn from his high school library encyclopedia in his wallet next to his first news clipping. In black and white it’s hard to tell Spooner was albino and not just a chalky, balding professor in a dark Edwardian suit.

Around the time he discovered Spooner, Benny started his hobby of categorizing the skin tones and complexions of people, trying to catch them in his coloring books by blending crayons, later paint sets, and making up his own races – chestnuts, butters, nougats – that was Benny – cocoas, maples, Hershey’s, almonds, peanuts, peaches, cherries… Most were mixes, hybrids, alloys, he mused, like bronze. Mutts. Someone on a radio groused about “mongrelization of the races,” but already he had read mutts were stronger and plants healthier and blue bloods got hemophilia.

What about that, Aunt Lala? “

“Mixed marriages never work. It’s the children who suffer, like those war babies. Nobody accepts them.”

He couldn’t fathom the concept. “What about mama and papa? They don’t match. Mama has red hair and she’s a Jew, like me.”

“You’re Italian too.”

“I’m platinum.”

His aunt gave him a disapproving look. “The things you kids make up, honestly.”

None of this made sense to young Benny. As a child, he attributed traits, vulnerabilities and powers to each shade of named. Peanut-Butter people could fly, for example, but rarely did so because they tended to be acrophobic. Chick Pea people could read minds, but couldn’t remember names. The extremely rare Porcelains – to which he belonged, possessed the super-power of invisibility, not by being transparent, but of causing people to ignore or look away from them.

As a dramatically monochromatic being, he belonged at the far end of the human spectrum. People called themselves white, weren’t all that white, no more than American Indians were red, or African-Americans were black. He liked people’s colors, and some he found more sexy than others. He liked curvy women, and favored bronze hues, and not by accident did he find Makeda attractive despite his efforts to stay cool.

Growing up, Benny, oddly, felt the most self-conscious among his own kind. When he was ten, his mother — always forward looking — took Benny to a support group meeting for children with albinism and their parents. He didn’t like the other albino kids, not because their skin was as white as his, but because he found most of them dopey and ignorant – the kind who only looked a comic book pictures and never read the bubbles and captions, the kind who spit and punched, and who liked Roy Rogers better than Buck Rogers or Flash Gordon, and didn’t know that the theme from the Lone Ranger was from Rossini’s William Tell Overture.

Reading compulsively, outside school, he shunned the textbooks of the times that left out so much, and implied that slaves didn’t have it so bad in the antebellum South, and scripted Reconstruction pretty much in the same terms as D. W. Griffith’s racist epic Birth of a Nation.

The sixties came too late for him. The counterculture’s superficial celebrations of weirdness failed to impress, as did mainly the ambiguous, over-maleness-in-black-turtleneck Beat Generation.

He didn’t care to be hip, but the politics, that was different. He hated the mindlessness of the arms race and the Vietnam war. In 1967, he found himself marching in a demonstration – mainly following a radical, free-love girlfriend-of-the moment – against U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Suddenly, he was in a crush with thousands of protesters marching on Wilshire Boulevard. It was the week after mounted LAPD had gassed and clubbed demonstrators against a LBJ in front of the Century Plaza Hotel, where the president had been attending a conference.

Benny, usually reserved, felt a catch in this throat at the sight. Ordinary-looking people of all ages moved, shoulder-to-shoulder, spread from curb-to-curb, flowing all the way down the wide Miracle Mile. Like many of those present at such an event for the first time, he discovered that there were many other kindred spirits out in the world who felt as he did, no longer lone dissenters. These, he felt, where truly “his own kind,” at least for those fleeting moments.

“What do we want?”

“Peace!”

“When do we want it?”

“Now!”

Mounted police rode along the curbs in riot gear, and Ben could see tac-squad snipers watching from the roofs and windows of the high rise buildings.

“Peace now!”Or as Benny shouted it, “niece pow, niece pow!”

The demonstration got little news coverage. Nobody important from the paper made him out in the crowd, breaking the fourth wall of feigned news reporters objectivity. Only his usual cohorts of little consequence marched with him – underdogs all, as he regarded himself, and took pains to cultivate.

9. LA PALETA DE EZEKIEL

Benny riffles papers on his desk aimlessly. Can’t concentrate. He wanders upstairs to the third-floor composing room occupying the long low structure over the presses between the Times and Mirror buildings. Ostensibly he has gone up to check proofs.

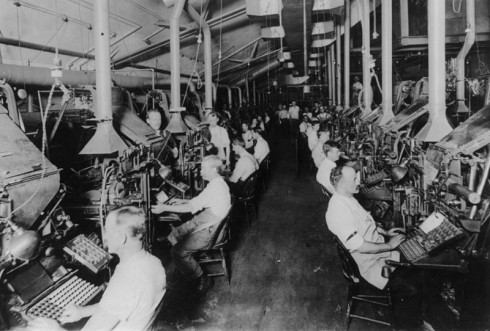

He can feel the rumbling of the presses faintly as he crosses the floor, threading rows of Linotype machines that loom like allosaurus skeletons, manned by pale, wizened operators in green eye shades. He moves on through the Mirror Building ad and circulation offices and takes another elevators down, stepping out onto the street discreetly from its side doors.

From there it’s up to Broadway where he blends into the crowds of shoppers coming in and out of stores, a mix of white collar workers starting to get out of the offices and Latinos from nearby neighborhood. Right away he feels better.

From there it’s up to Broadway where he blends into the crowds of shoppers coming in and out of stores, a mix of white collar workers starting to get out of the offices and Latinos from nearby neighborhood. Right away he feels better.

A few blocks down Broadway, Benny slips into the cavernous Grand Central Market where he can lose himself in what feels like a perpetual fiesta. He takes in the colors, music, chatter, the smells of iced fish, eyes staring up at him as he passes, delicious smells of chorizos, carnitas, softness of flowers, brilliance of local and exotic fruits, moist fresh-cut seasonal greens, the panderias with hot doughy cinnamon buns, best of all, crowds of shoppers, brown-skinned, with Toltec eyes, speaking familiarly Mexican-accented Spanish, not much English here, mostly by choice. Peppers, mangoes, pineapples, bananas – spirited vendors outdoing each other calling out bargain offers and inducements.

Everywhere, images of La Virgin de Guadalupe, arms wide with open her green robes and baby Jesus peeking out from her skirts, offering her goddess blessings from the white glass of seven-day candles. Earnest, dark eyes, broad-beamed women with shopping bags, pull pranksterish kids through the narrow aisles. Benny feels afloat in Spanish – no Muzak, no sterile freezer cases, no wobbly shopping carts, no anonymous checkout stands with bored suburban moms who can’t wait to get back in their station wagons.

The Grand Central reminds Benny of when he was very young and his mother still was happy and took him along for Saturday shopping in Boston’s North End, along with her sister and Benny’s cousin Paula. Benny takes and breath and stops for his usual iced tamarind drink at a stand deep enough inside the Grand Central to leave the rest of the world behind.

He takes this kind of break often, buying ingredients to cook at home for his kids when they are with him, and even just for himself. This time, however, something different happens. He nearly collides with Preacher man, brassiere cap at all, spying into a glass case of Mexican dulcets.

Benny had not seen him since the afternoon when Makeda chased him. Benny sidles over. Preacher smells faintly floral, not rancid, as Benny would have expected. Preacher Man straightens and blinks.

Benny had not seen him since the afternoon when Makeda chased him. Benny sidles over. Preacher smells faintly floral, not rancid, as Benny would have expected. Preacher Man straightens and blinks.

“ Hi. I’m Benny. I work for the paper. You know, the Times. I think you’ve seen me over by the building on Spring Street.”

Preacher stands tall, widens his eyes and raised one hand, pointing heavenward like Charlton Heston playing Moses. “End times!”

“No, L.A. Times.”

“Thou are the White Angel of End Times come to sound thy horn!”

“No. I’m an albino, actually.

“All be known of God’s word, sinners, going to hell!” Preacher man’s voice rises above the din of he market. A few people stare, but most just keep moving past them.

“Just a man with no pigment.” Even this nut has to type-cast me. Why does every albino has to either be an angel, or some comic-book nemesis?

Benny waves his press card, feeling foolish. “Makeda, my friend, the woman who works with me, wanted to talk to you. Maybe you saw her come out of the building the other day.”

“I know who you are…. Do you?” Preacher man then turns to the woman behind the freezer case and points at a pale green, lime-coconut paleta. The counter woman’s wide-spaced, dark chocolate eyes regard us with the discreet watchfulness of a psych ward attendant.

Preacher Man hands her a crumpled five-dollar bill. She takes it on tip-toes and hands off the paleta.

“You are not going to hell,” he tells her. His voice softens to normal now. “On the other hand, he IS! He will go straight into lakes of fire” Preacher waves the paleta at Benny and points downward with his other hand. The woman makes a sign of the cross, puts the fiver in a cigar box and starts counting out change.

“Keep the change.” Preacher waves the Latino Popsicle at her. Either Preacher Man doesn’t know how to count, or he’s a big tipper, surprising Benny.

“Thank you, senor Ezeequle.” The woman hints a smile at Preacher that Benny takes as flirtatious. It dawns on Benny that Preacher Man possibly has an actual name – Ezekiel — and a life beyond that of being a downtown annoyance.

Ezekiel? That seems apt. Benny extends a hand. “Hello, Zeke. Nice to meet you.”

Preacher man sticks the paleta in his mouth and pumps Benny’s hand vigorously. “Repent, ghostly sinner!”

“Okay. I repent.”

“Come to Jesus.”

“May I get a paleta first?”

Zeke the Preacher signals to the woman. “Sonia, por favor, una paleta por este pobre pecadore.”

“I was only kidding, but okay, coconut, please.” Benny pulls out a dollar, but Sonia waves it away and hands him the iced pop of his choice. She flashes another coy smile at Zeke.

“Thanks, Zeke.” Benny takes the paleta. “Can I talk to you somewhere privately for a minute?”

Preacher heads up the aisle and Benny follows. They exit the Grand Central on the Hill Street side. Down the block, Zeke steps into an alley, and stops next to some trash barrels. Benny follows, keeping his distance, just in case. “Okay. This is good.”

“Your icy is going to melt.” Suddenly, Preacher man seems to solicitous and normal, but Benny remains guarded, knowing manic-depression all too well.

Benny peels off the cellophane and goes for his paleta. “So much better than popsicles1 I can really taste the coconut.”

“Coconut!” Preacher Man goes ballistic again, shouting. “The Avenging Angel will appear, breathing fire in the grove of coconuts to announce Armageddon. You’re all going to ha-ha-hell!” Off the deep end again, he bellows this over and over down the alley.

Jesus. Here we go again. Benny waits until Preacher’s ranting subsides.

“Look, Zeke, or whatever your name is; all I want to know is where my friend Makeda can reach you. Do you have a phone or address I can give her? I don’t know what she wants to talk with you about. None of my business.”

“Coconuts will fall. Coconut Grover. Jesus says kill Kennedy. Going to hell. Those in the orchard will be saved.”

“Kill Kennedy?”

“Coconut Grover says we must smite the sinner. And the temple will be destroyed, the nations will be consumed in fire. ”

“What the fuck?” Benny starts to back out of the alley.

“We got the fire already. I’ll just be going now.”

Zeke pulls something small, black and metallic from under is camo jacket. “Holy or holies! Praise the Lord!” Zeke looks heavenward into the smog waving the object.

Fuck, he’s got a gun!

Benny backs slowly out of the alley. “Okay. I hear you. Praise the Lord” … and let me out of here.

Out of nowhere, a car pulls into the alley. It brushes close by Benny and stops in front of Preacher Zeke – a black Lincoln sedan. Someone opens a back door. A deep male voice calls Zeke, who gets into the sedan, the door closes and it rolls away.

Benny writes the license of the car on the palm of his hand, not knowing what he’ll do with it or why.

####

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.