Thinking about Oz

Leslie Evans

Oz Reimagined: New Tales from the Emerald City and Beyond. Edited by John Joseph Adams & Douglas Cohen. Las Vegas, NV: 47North, 2013. 365 pp.

The Living House of Oz. Edward Einhorn. Illustrated by Eric Shanower. San Diego: Hungry Tiger Press, 2005. 238 pp.

The land of Oz is a beloved American legend. It is known to most people from the 1939 musical film starring Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, and Jack Haley, still revived regularly on television and available on DVD. The film captured the look of the place much as it had been envisaged by its creator, L. Frank Baum, back in 1899: a vividly colored fairyland filled with odd but simple people and many magical creatures, from witches to live trees, winged monkeys, and Oz’s famous automatons, the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. These images are engrained on the American psyche.

Still, the film misrepresented Oz as its history unfolded in Baum’s thirteen later Oz books. One oddity was the decision to cast the Munchkins as dwarfs (today: little people). It works well in the film, but as the tales go on into many volumes there is no way to have the people of one of Oz’s composite four countries – Munchkins in the east, Winkies in the west, Gillikins in the north, and Quadlings in the south – be far smaller than the others. Actually in The Wizard of Oz Baum describes them:

“They were not as big as the grown folk she had always been used to, but neither were they very small. In fact, they seemed about as tall as Dorothy, who was a well-grown child for her age.” In the later books Munchkins are no smaller than anyone else, and the American habit of referring to cute little children as “Munchkins” would make no sense in Oz.

The greatest false note was the decision by MGM executives, fearful that such a flamboyant fantasy would corrupt the minds of American children, to make the whole thing a dream. That, and its concomitant and ever repeated message, There’s no place like home. Kansas couldn’t possibly compete with Oz and anyone who knows what happened to Dorothy afterward knows that she soon left Kansas far behind and Oz has been her home ever since.

Baum styled himself the Royal Historian of Oz. His records show that the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, left to rule Oz after Dorothy and the Wizard departed for America, were overthrown by an army of women led by General Jinjur. She in turn was permanently replaced by Ozma, a descendant of Lurline, the fairy queen from the Forest of Burzee, who had first enchanted Oz so that its people never grew old and imbued it with its magic.

The Wizard, in one of his less savory deeds before the days of Dorothy, had kidnapped the baby Ozma. To prevent her ascending the throne he gave her to the Gillikin witch Mombi. Mombi transformed Ozma into a boy named Tip. Tip’s adventures are recorded in the second Oz book, The Marvelous Land of Oz, which ended with the, for that time, daring transgender transformation in which Glinda turns Tip into Ozma, a young girl. Ozma has ruled Oz ever since, and appears in all of the succeeding books.

Dorothy returned to Oz four times. She is blown off a ship in a storm, falls into an underground kingdom during an earthquake in California, walks there on a magic road, and finally, is brought there by Ozma to live permanently, along with her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em. Dorothy is made a princess of Oz and never returns to Kansas.

The great attraction of Oz is that it is an American fairy tale. It’s a you-can-get-there-from-here place. Its heroes and heroines are mostly American children, not the princes, princesses, or wood cutters of traditional European fairy stories. There is not only Dorothy Gale but Betsy Bobbin, Trot Griffiths, Button Bright, Peter Brown from Philadelphia, and William “Speedy” Harmstead from Long Island, New York. A few adults make it as well: Dorothy’s Uncle Henry and Aunt Em, the Shaggy Man, Captain Bill Wheedles, and of course, the great original, Oscar Diggs, better known as the Wizard.

The other unavoidable conflict between the film and the histories was the necessity to make Dorothy’s film companions men in costumes. They did it marvelously well. Ray Bolger’s Scarecrow was inimitable, and Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion was a classic act. But in Oz the lion was a real lion, the Tin Man, depicted thousands of times over forty years in John R. Neil’s illustrations, was really made of tin, with arms and legs that were thin jointed rods with no place in them to conceal a meat arm or leg. And the Scarecrow was filled with nothing but straw, his mouth only painted on. I suppose his voice materializes like the sound from a television speaker which only gives the illusion it is coming from the person pictured on the screen.

Oz is now more than a hundred years old. L. Frank Baum had written fourteen volumes before his death in 1918. After that his publisher, Reilly and Lee (they were Reilly and Britton during Baum’s lifetime but changed their name in 1918), engaged Philadelphia children’s author Ruth Plumly Thompson, who penned nineteen more, taking the series up to 1939. Then, like Sherlock Holmes, any number of authors have tried their hand at adding to the oeuvre, from artist John R. Neil, who had illustrated all but The Wizard of Oz, who added three undistinguished titles, to Jack Snow, who wrote two more in the late forties, all under the Reilly and Lee imprimatur, to many others in later years from other publishers.

I remember my father reading The Wizard of Oz, Ozma of Oz, and The Road to Oz to me and my sister when I was eight or nine. I looked over his shoulder and absorbed images that have remained with me for a lifetime: The mechanical giant with a hammer who guards the mountain cave in Ev that leads to the vast underground kingdom of the Nomes. The silhouette of the Shaggy Man after the king of Dunkiton had given him a donkey’s head, brooding in a wilderness by moonlight. The lost boy Button Bright in his sailor’s suit sitting idly and unconcerned by the side of the road, digging in the dirt with a stick. Johnny Dooit’s sand boat that will take Dorothy and the Shaggy Man across the Deadly Desert to Oz.

I started collecting Oz books when I was about twelve and by my mid-teens had the whole thirty-three. I gave the set to my first wife’s younger sister when I moved from San Francisco to New York in 1967. After I returned to Los Angeles in 1982 I collected them all again.

So today we have Oz Reimagined. Editors John Joseph Adams and Douglas Cohen have collected fifteen stories by sixteen widely published authors of fantasy, science fiction, and in some cases, other children’s books. The mission seems to have been to offer an adult and mostly dystopian take on the fairyland.

Gregory Maguire, author of Wicked, provides a Foreword. And though his own Oz books emphasized the negative, he seems, of all the contributors, to best understand what Oz is about. He describes himself “as a man nearing sixty who recognized in Oz, more than half a century ago, a picture of home.” I have thought of it that way for even longer. Every Oz story contains an adventure. They are filled with bizarre and often hostile creatures. Eight of the thirty-three Baum and Thompson books involve attempts to conquer Oz. But at the core there is Ozma’s court. We know that in the end Ozma, with aid from Glinda, the good witch of the South, and the Wizard, who now knows a good bit of magic, will prevail. The stories epitomize what Jan Struther in her poem Sleeveless Errand called “The savour of the strange, The solace of the known.”

Maquire puts his finger on how this juxtaposition is achieved, by a radical disconnect between a large part of the population and even their nearest neighbors. The peaceful portions and the malevolent little enclaves are mostly separated by a remarkable lack of interest in exploration:

“I found the insularity and even parochialism of Oz’s separate populations puzzling and, maybe, worrying. Racist even, though I hadn’t a word for it yet. Troublingly myopic, exceptionalist. Certainly lacking in intellectual curiosity. When Dorothy first arrived in the land of Munchkins, the kindly Munchkin farmers told her what they’d been told about the EmeraldCity and about the Wizard. But none of them had had the gumption of Dorothy to pick themselves up and go see for themselves. No firsthand experience. Few of them could predict what kind of population lived over the horizon. None of them cared.”

This is true not only of the large subdivisions with their predominant color schemes – blue for Munchkinland, yellow for the Winkies, purple for the Gillikins, and red for the Quadlings – but for the endless subcountries with their own kings and courts, and downward from there to city-states, towns, and finally communities of just a few individuals living in clearings in the forest. The larger subdivisions are populated by humans: Oogaboo in the far northwest, whose queen, Ann Soforth once raised an army to try to conquer Oz, Mudge at the diagonally opposite corner; “kingdoms” named Pokes, Patch, Corabia. Then there are the endless magical enclaves: China Country where all the inhabitants are made of porcelain; elsewhere we encounter communities of living books, living torpedoes, mist maidens, people whose feet are fastened to the ground while their furniture runs around as needed.

There are little towns and kingdoms under the ground, on high mountains, and even invisible in the air overhead. Most seem oblivious to the larger Oz, and either hostile to people who wander into their territory or intent on converting them to their own peculiar way of life by transforming them in some usually unpleasant way.

In The Lost Princess of Oz (1917) Dorothy, the Wizard, and several others find their way to the city-state of Thi, a small town surrounded by a thicket of thistles, inhabited by Alice-in-Wonderland type creatures with heart-shaped bodies and triangular heads. On telling their leader, the High Coco-Lorum, that Thi is part of Oz, this person replies:

“It may be, for we do not study geography and have never inquired whether we live in the Land of Oz or not. And any Ruler who rules us from a distance, and unknown to us, is welcome to the job.”

These small kingdoms and enclaves usually appear in only a single book and are never heard of again. In some cases, such as Oogaboo or Rash, they are central to the plot of a particular book. Most of the others are just impediments along the way, such as Chimneyville in Jack Pumpkinhead of Oz or the Hoppers and Horners in The Patchwork Girl of Oz. I have come to think of most of these ephemeral places that don’t figure in the central story as filler.

In Oz Reimagined only a few of the authors show any awareness of the Oz of the written canon. Nine of the fifteen stories get no further than having a Dorothy, a Wizard, a Scarecrow, a Tin Man, and a Lion. They could have been written after watching the movie. There is some justification for this because of the far wider distribution of the film than the books, but it is also like commissioning a book of new tales about King Arthur in which most only take us as far as the youth removing the sword from the stone and leave out Camelot, Lancelot, Guinevere, and Sir Galahad. And far too many stories have winged monkeys, characters that after the first book are extremely rare in an Oz story.

First, the retellings of the original story:

Rae Carson and C.C. Finlay in “The Great Zeppelin Heist” offer a pre-Dorothy tale in which the newly arrived Wizard proposes marriage to the Wicked Witch of the West, but is tricked out of his engagement gift.

In “Dead Blue” David Farland imagines Dorothy as a technomage, the Tin Man as a cyborg, his flesh parts replaced with microcomputer-controlled bionics, the Wizard a harmless conman who ended in Oz when his star ship slipped through an unexpected wormhole. Dorothy and her companions are on the way back from killing the Wicked Witch of the West and intend to depose the imposter Wizard.

The darkest story in the set is Robin Wasserman’s “One Flew Over the Rainbow,” where Dorothy, “Crow,” “Tin-Girl,” and “Roar” are all patients in a mental institution.. Crow got her name because of a massive tattoo of a flock of crows running up her back to her neck. The narrator, Tin-Girl, so named because she cuts herself and is covered with hard scars, tells us that Crow’s brains don’t work right while she, Tin-Girl, has no heart. Get it? Roar is a big thuggish fellow. Tin-Girl trades painful sex to “the Wizard” in exchange for drugs, and a chance to escape. The man who prescribes their daily tranquilizers is Doctor Glind. Dorothy has hair dyed electric blue and paints her nails black. There is nothing Ozish about this one. It could be called Ozploitation.

Ken Liu appropriates the names of the first-book characters for “The Veiled Shanghai,” a science fiction story set during the May Fourth Movement, the anti-imperialist protests in 1919 over the ceding of Chinese territory to Japan in the Treaty of Versailles. This also has nothing to do with Oz. It is given a fantasy gloss by adding an other-dimensional second Shanghai. There is an Uncle Heng and Aunt En and a Dorothy Gee who uses her English name because it is more chic. She lives on Kansu Road, which gives her the opportunity to intone “I’m certainly not on Kansu Road anymore” when she shifts to the other dimensional Shanghai. In the second Shanghai she follows a trail of yellow bricks mixed into the cobblestone streets to find the Emerald House of the Great Oz. She picks up the obligatory companions, a scrawny English boy nicknamed Scarecrow, a robot lumberjack called Tin Man, and a big opium addict called Lion. The Great Oz turns out to be Sun Yat-sen and the Wicked Warlord who Dorothy vanquishes is the real warlord Yuan Shih-kai.

Kat Howard’s “A Tornado of Dorothies” runs the film back to the beginning again, with the events of The Wizard of Oz as an endless Groundhog’s Day loop in which new Dorothies enter by falling on the Wicked Witch of the East, progress through the story, then become ghosts to be succeeded by the next “Dorothy.” The most successful Dorothies move on to become other characters, a Glinda, for instance.

Jane Yolen in “Blown Away” has Dorothy carried off in her house by the tornado, but returning years later, grown up and having been a high wire walker in a circus and never gone to Oz at all.

Orson Scott Card sets his “Off to See the Emperor” in Aberdeen, North Dakota, while Baum and his family lived there before he wrote The Wizard of Oz. He has Baum’s son Frank Joslyn Baum go on an other-dimensional adventure where he seeks the Emperor of the Air, making Baum’s later wizard story a much altered version of his son’s wanderings.

Even the stories that get past 1899 and the first encounter with the Wizard are often dispiriting. Dan Baily in “City So Bright” follows a Munchkin building polisher whose dangerous work high on scaffolding far above the ground is made still worse as his workmates are murdered by the government for even mildly criticizing the Wizard. In Jeffrey Ford’s “A Meeting in Oz” Dorothy has grown up back in Kansas and become a murderer. Returning to Oz she tries to assassinate the Wizard but he has her killed instead.

These tales are well written by respected authors, but they have little to do with Oz, even an adult Oz where the perils of sex, old age, death, and betrayal would reasonably find their place. The best of the lot are “Emeralds to Emeralds, Dust to Dust” by Seanan McGuire, “Lost Girls of Oz” by Theodora Goss, “The Boy Detective of Oz: An Otherland Story” by Tad Williams, and, the most authentically Ozish in the collection, Jonathan Maberry’s “The Cobbler of Oz.”

Seanan McGuire imagines that the steady stream of outsiders who have found their way to the fairy country has expanded into a flood. The natives become bitterly resentful of the “crossovers,” who end in massive slums, wracked by crime and drug addiction. Even Dorothy has to be expelled from the palace, as popular resentment is too great for Ozma to retain a foreigner in her inner circle. In this fraught situation Ozma asks Dorothy to solve the murder of a Munchkin in the center of the crossover slum. As tantalizing asides, Dorothy’s roommate is Jack Pumpkinhead, who has had a falling out with Ozma, and she herself is gay and having an affair with Polychrome, the Rainbow’s daughter.

Theodora Goss take an opposite tack on crossovers. Rather than trying to keep them out and stigmatizing the ones who arrive, Ozma is deliberately transporting sexually abused girls to Oz. Outraged at their treatment in America, she is building a massive army of rescued girls to conquer the United States and place it under a more civilized ruler. The girls are supplemented by Wogglebug hatcheries producing thousands more of the country’s leading intellectual, the giant insect H. M. (Highly Magnified) Wogglebug, T. E. There are Tik-Tok factories turning out legions of the wind-up mechanical men, and Jack Pumpkinheads are being made by the thousands, their wooden bodies being vivified by Dr. Pipt’s Powder of Life, now being produced in huge vats in the Gillikin country. Lots of Oz characters make cameos in this story, from Jellia Jamb to Ojo. And the Shaggy Man proves to be no mean fighter with an assault rifle in an encounter with a detachment of hostile nomes.

Tad Williams’ story, as promised, is an Otherland tale. Otherland, which I highly recommend, is a four-volume science fiction saga published between 1996 and 2001. The premise is that a group of fabulously wealthy billionaires undertake a secret project to build a series of persistent-world virtual reality simulations with the aim of uploading their consciousness into them to achieve a form of immortality. In his Boy Detective ramble the action takes place within the Kansas portion of a once bilateral Oz simulation. Code corruption has shut down the Oz part, but in this Kansas the Tin Woodman runs a factory while the Cowardly Lion is the leader in the nearby forest. Omby Amby, the Soldier with the Green Whiskers, who here instead of comprising the entirety of the Royal Army of Oz, is known as the Policeman with the Green Whiskers, is found dead, beheaded. The Wizard appears as Senator Wizard of Kansas. The Glass Cat is up to her usual mischief, while the eponymous Boy Detective is a system troubleshooter named Orlando Gardiner. In the real world he is a dead teenager. Here in the Otherland simulations he lives on as an immortal technician, the only character aware that the simulation is not real. This all works rather nicely even if it isn’t Oz and isn’t “real.”

And finally we come to “The Cobbler of Oz.” This is the closest to a traditional Oz episode. A young winged monkey whose wings are deformed and too tiny to fly visits the cobbler’s shop seeking a pair of walking shoes. He tells her about an ancient pair of magical walking shoes with which a long-gone princess was able to cross the whole country in a few steps. In fact, he produces from a cupboard the very shoes, now badly worn and missing many of the silver dragon scales that gave it its power. He offers to loan them to the little monkey if she will cross the Deadly Desert and try to get replacement scales from the original dragon. Only at the end do we come to understand that these are the silver slippers that will later play a part in Dorothy’s first Oz adventure.

In summing up, I would think that the century that stands between L. Frank Baum’s fairyland and the hopeless and oppressive Oz imagined by these authors must say something about what has happened to America. Oz had its share of witches – old Mombi long outlived her sisters in the Munchkin and Winkie lands. Ruggedo, the one-time king of the Nomes, was behind four of the eight attempts to conquer Oz. (Baum spelled it Nome, while Ruth Plumly Thompson reverted to the more standard Gnome.) There were the Kalidahs and the giant spider of the original book, and many more dangerous and evil-intentioned creatures who came later. Yet these people, entities, and beasts were all defeated, neutralized, or left alone in their own small corners. Oz is a sunny land with a contented people, happy with their fairy ruler and perfectly satisfied to live under an unelected monarchy.

Ruth Plumly Thompson published the last of her Reilly and Lee Oz books in 1939, the year that Hitler and Stalin invaded Poland, touching off World War II. After years of bloody fighting the Nazi menace was defeated, followed by an unexpectedly short-lived period of American peace, prosperity, and international influence. With the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the Sixties radicalization, the rise of the Radical Right, and finally the onset of many measures of U.S. decline from the 1990s it has become more difficult to imagine that the future will be, as our Victorian ancestors believed, a steadily improving triumph of progress, improving standards of living, and a reign of reason and justice. It is easier to imagine Dorothy as a lunatic, a demented killer, a mere name to be pasted onto a long-ago struggle against warlordism in China, or a Wizard or an Ozma running an oppressive bureaucratic state complete with secret police and dehumanizing slums.

* * *

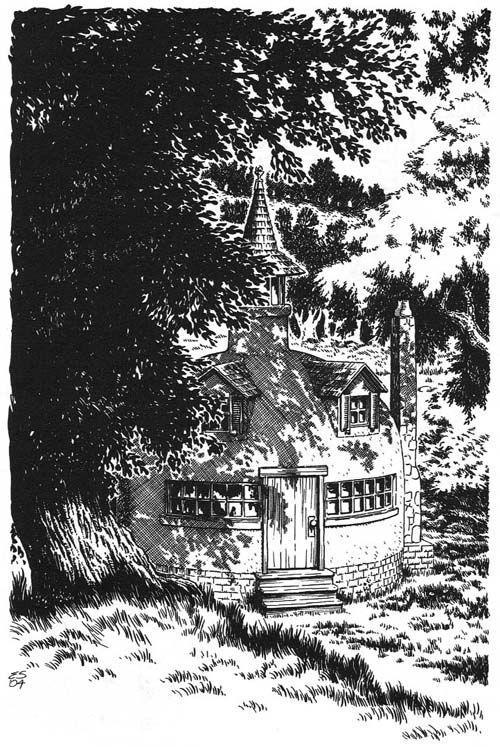

Edward Einhorn is a New York little theater director and novelist. This is his second Oz book. The first, Paradox in Oz (2000), was a time travel puzzle story that only partially captured the spirit of the place and got a bit too complex. In that book he introduced his parrot-ox (pun) Tempus, a creature with the body of an ox but the head and wings of a parrot who can fly backward and forward through time and materialize multiple versions of himself from different time streams. Tempus returns for a small fly-on in The Living House of Oz. This time around Einhorn shows a surer touch and can reasonably be added to the canon. At first I shied away from the live house concept. Center stage is one of those Oz houses originally drawn by John R. Neil: a dome with a wide row of windows on the ground floor that look like teeth, two large upstairs windows that look like eyes, and tall chimneys on each side pointed like arms at the sky.

What Neil added in his own The Wonder City of Oz (1940) was to bring his houses to life. They talked, and many of the household objects inside were alive as well, creating a cacophony that was unbearably frenetic. Einhorn has adopted this premise, but tamed it and given it a better grounding. There is only one living house, and yes, everything inside is alive and chatters away, from a mobile hat rack who styles himself the Earl of Haberdashery to every pot, chair, and doorknob. But there is a reason. The human inhabitants are thirteen-year-old Buddy and his mother Mordra. She, it seems, is a dead ringer for the long-deceased Wicked Witch of the West. And she is also a powerful sorceress. The pair are in flight from an other-dimensional Oz ruled by a Wizard every bit as dictatorial as the worst imaginings of Oz Reimagined. Happily this is an offstage land.

Mordra and Buddy are being sought by the Phanfasms. These were evil shape changers first encountered in L. Frank Baum’s The Emerald City of Oz, one of the several peoples enlisted by Ruggedo the Nome King in one of his many attempts to become the ruler of Oz. The Living House has a pair of big wooden legs, so when Mordra fears she has drawn too much attention to herself she has the house stand up and walk away to a more secure location, usually setting down in some forest clearing. This is an engaging concept.

While the house is camped in the little kingdom of Tonsoria (naturally, a place absorbed with hair styling, wigs, and full of comb and scissors trees) Buddy is kidnapped. In trying to rescue him, Mordra’s sorcery is discovered by Glinda and she is arrested for illegally practicing magic. There are various adventures that get Buddy to the Emerald City to rescue his mother from Ozma and Glinda, Tempus the parrot-ox gives a helping hand, there is a really unexpected surprise, then the Phanfasms appear and, as an old fellow I used to know would say, it’s Katy bar the door.

There is at least to some degree a welcome adult sensibility about the Living House. Mordra suffers from her ugliness and is not made pretty at the end. She is unwilling to give up her magic, which protects her child, no matter what the law says. Ozma and Glinda try to resolve the problem and do not become monsters in doing so.

Oz books have always been visual as well as textual. Baum, happily for us, got rid of W. W. Denslow, who illustrated The Wizard of Oz. Denslow limned the first patterns for the Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow, but his Dorothy was chubby and far too young, while his other characters were overly rotund and a bit goofy. John R. Neil took over with The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904). Neil’s first Oz book owed much to Denslow but by his second entry, Ozma of Oz, in 1907, his own style had solidified. Dorothy became a slim, blond, stylishly dressed young girl. The Tin Woodman and the Scarecrow became slimmer and more sober. When Ozma joined the cast at the end of The Marvelous Land of Oz she had red hair and looked like a ten-year-old. By Ozma of Oz she has black hair, looks to be in her late teens, and wears a more form fitting dress. She is always seen thereafter with one large red flower covering each of her ears.

Under Reilly and Britton and Reilly and Lee the Oz books contained full color paintings, usually twelve, by Neil. These were canceled to save on printing costs after Thompson’s 1935 The Wishing Horse of Oz. Thompson’s last four books had only black and white drawings. Except for some facsimile editions by the International Wizard of Oz Club and Books of Wonder, all the editions after 1935 omitted the color plates.

Neil did his most elaborate paintings for the sixth book, The Emerald City of Oz (1910), in the belief that this was to be the very last of the series. But when Baum found that his other books didn’t sell as well and that thousands of children were writing to him demanding new stories about Oz he resumed the series with The Patchwork Girl of Oz in 1913.

Neil slacked off a bit a few years into Ruth Plumly Thompson’s reign as Royal Historian. At an Oz conference this year one speaker claimed that Neil would dash off all the illustrations for the annual Oz book in a single day.

No matter, his work became so identified with the look of Oz and its inhabitants that post-Thompson writers have often failed to find traction in large part because their illustrators were too inauthentic. On this score Einhorn has been fortunate in teaming with Eric Shanower. A talented artist, Shanower is the author as well as illustrator of his own series of Oz graphic novels such as The Salt Sorcerer of Oz and The Forgotten Forest of Oz. For The Living House, apart from the full color dust jacket, he offers a generous number of fine pen and ink drawings.

His work is more meticulous and detailed than Neil’s. His frontispiece for The Living House shows it at rest in a leafy glen, adding greatly to the story’s credibility. And in his several crowd scenes, all of the traditional Oz characters, both by Baum and Thompson, are readily recognizable, from the Woozy to Tik-Tok, Kabumpo the Elegant Elephant, and Sir Hokus of Pokes. Shanower is not slavishly copying Neil, but stays close to Neil’s patterns as the canonical originals.

The character of Oz shifted somewhat when Ruth Plumly Thompson replaced its creator, with The Royal Book of Oz. Baum’s folksy dialog disappeared, and Dorothy no longer said “I s’pose” and “it’s terr’ble.” Gone also were the quaint philosophical discussions and debates between the magical creatures over the relative advantages of their particular construction and the limitations of “meat people.” Thompson wrote more traditional fairy tales, used even more puns than Baum, and favored her own characters, such as Peter from Philadelphia and Jinnicky, the Red Jinn, whose body was a large jar in which he lived like a turtle in its shell. Though her tales were smooth and had a good bit of Oz feeling, some of the mystery had departed with Baum’s old fashioned prose and odd discussions, usually carried on during the night, when the magic creatures sat up talking, as they had no need for sleep. For those of us who wanted to see Oz continue we accepted Thompson, with just a few silent reservations. Some people speak of a canon of forty books, including John R. Neil, Jack Snow, and the now mostly forgotten Rachel R. Cosgrove and the Eloise Jarvis McGraw and Lauren Lynn McGraw writing duo. Beyond a certain point the image of Oz shimmers and becomes opaque, no longer authentic.

In the end, Oz can take only so much adultifying. Whatever evils or dangers are found or added, it must still be home and a refuge for those of us who must live our regular lives in one or another version of Kansas.