The Secret Behind L.A.’s Literature

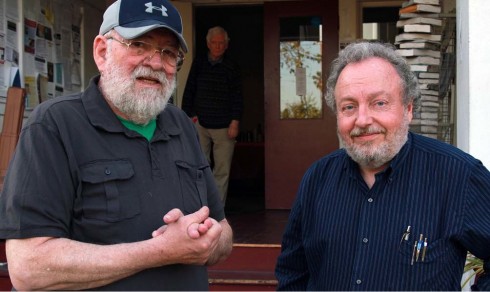

Lionel Rolfe (left) with Gerry Nicosia, author of “Memory Babe,” the major biography of Jack Kerouac and the beats. The photo was taken at Beyond Baroque in Venice.

By LIONEL ROLFE

It all began in the coffeehouses a couple of centuries or more ago in London where such institutions as media and insurance took on their modern forms, for better or for worse.

The coffeehouses had names like The Fifth Estate and Lloyd’s of London. They all shared something in common. They imbibed a highly seditious drink, a coffee brew from Turkey called Kaufy. Most folks regarded the potent new drink the same way police viewed pot in the coffeehouses of Los Angeles and San Francisco in the ’50s and ’60s.

After the Gold Rush, Bohemia and coffeehouses developed in San Francisco with such characters as Herman Melville and Mark Twain. The bohemian was the foundation of good writing in California, first in San Francisco and then in Los Angeles.

Mark Twain comes to Southern California through the Newhall pass. It was in this area gold was first discovered in 1842 in nearby Placerita Canyon, not 1848 near Sutter’s Mills in Sacramento, the usual first dating of the Gold Rush. Twain probably visited Southern California while exploring the original gold fields in the 1860s. In 1884, Charles Lummis published Tramp Across the Continent, describing his trip to Los Angeles. Lummis became a seminal figure in the development of Los Angeles bohemia. He was the first city editor of the Los Angeles Times, the first librarian, and as publisher of the The Land Of Sunshine which became Outwest in 1901, eventually became Jack London’s first publisher. 1901 was also the year John C. Van Dyke published his masterpiece about Southern California, The Desert, a brilliant description of the Mojave’s many different colors and attributes.

Bohemianism moved to Carmel after the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, and it was from Carmel the great bohemian migration to Los Angeles began. A good example of this is Ina Coolbrith, the Oakland librarian who served as Jack London’s mentor. She became involved in a romantic three-way with Mark Twain and Brete Harte. She grew up in Los Angeles when it was still a pueblo, then moved north. In the late 1920s, she came back to the city of the angels to visit Charles Lummis at his El Alisal all stone castle in the Arroyo, shortly before both died. Others involved in 1906 in Carmel and then Los Angeles included Theodore Dreiser, Sinclair Lewis, Upton Sinclair and Mary Austin.

At the center of this group was California poet laureate George Sterling, who had lived at the Bohemian Club on the Russian River north of San Francisco. Sterling, the state’s poet laureate, was friends of all the bohemians, and he visited his friend Finn Frolich in Los Angeles in the 20s. Frolich built a sculptor studio there and dedicated it to his old friend Jack London. London had written about Frolich as a character in his book Martin Eden, published in 1906. It is no accident that the insides of London House, which still stands in an alley near the Paramount Studios on Melrose Avenue, looked like a ship, with its winding narrow stairs. There’s a bust of London on the house’s bow–Frolich did the same bust at Oakland Square and London’s Valley of the Moon.

We don’t think of Dreiser as a California writer, but he was here for quite a spell. He was so close to Sterling he took his beautiful wife to the Bohemian club on the Russian River and allowed Sterling to entertain and woo her by swimming naked in the river. He moved to L.A. in 1919. He had written Sister Carrie in 1900. In 1920, he began An American Tragedy in L.A. Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle in 1906, spent time in Carmel but then moved to Southern California in 1916 and spent most of the rest of his life here. His novel Oil published in 1927, is his great Los Angeles book. Recently it was made into a movie called “And There Will Be Blood.”

In the ’20s, Bohemia settled into the hills of Echo Park. A lot of what developed was in the circle of Jake Zeitlin, a bookseller. Aimee Semple McPherson was a famous evangelist and show woman, but she would sneak up into the hills behind her Angeles Temple and engage in bohemian orgies with Jake’s friends, who included photographer Edward Weston, Carl Sandberg and many others. So did Carey McWilliams whose classic Southern California: Island on the Land wasn’t published until 1946. He was the long time editor of The Nation, one of the country’s oldest magazines, friend of Jake’s, and his book was a classic of Literary L.A.

A ’20s renaissance developed around Jake and his bookstore next to the downtown library and in his Echo Park digs. Later after the war Anais Nin, and presumably Henry Miller, and a little later still, Charles Bukowski, hung around in the very same hills of Echo Park. Weston’s first show was in Jake’s bookstore in 1928. At the bottom of the Depression, Steinbeck was in Eagle Rock, getting his start as a writer, not too many miles away.

The end of the ’30s, 1939 to be precise, was a year in which everything changed. It was the height of the Southern Pacific’s great “Daylight” train, painted in orange and black, pulled by a fiery dragon monster of a machine, a great steam locomotive, which steamed into Union Station every day.

In literature, 1939 was a great year for the Los Angeles basin. There was a strange and volatile mix of bohemianism and the apocalyptical brewing. This was the year Aldous Huxley published After Many A Summer Dies the Swan, Thomas Mann was laboring away on Doctor Faustus while living in the Palisades. Malcolm Lowry began seriously writing Under the Volcano which was about the Day of the Dead in 1939 in Los Angeles. It wasn’t published until 1947. He writes about a Cabalistic descent into the maelstrom that was World War II. Day of the Locust was written in 1935 on a hot summer day filled with fire, the Depression, and assorted gloom and doom, leading the way from the essential hopefulness of bohemia, despite all their hedonism and what not. The book paved the way for Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 in the ’50s. 1939 also saw Grapes of Wrath, Day of the Locust and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep.

The Garden of Allah in Hollywood, at Crescent Heights and Sunset, was going strong, but despite the presence of names like Hemingway and so on, it was Dorothy Parker who drank and partied and parried the best there. Henry Miller capped it all off by checking into a Hollywood fleabag in 1941 and writing The Air Conditioned Nightmare published in 1945, which became holy writ around the coffeehouses of the ’60s in Venice, Hollywood and Echo Park, at the beginning of the counter culture. Also, Arna Bontempts wrote about Watts In Anyplace But Here in 1945. The Loved One by Evelyn Waugh came out in 1948.

The Beat scene of the late ’40s and ’50s in San Francisco was kept alive by poets and writers in Venice. Kerouac wrote an incredible several pages about passing through Los Angeles in Lonesome Traveler in the early 50s, and by the end of the ’50s, The Dharma Bums. Jack Hirshman, the incredible poet of the ’60s in Baghdad by the Bay, was teaching overflow classes on James Joyce at UCLA. He was very much a fixture in Literary L.A. Stu Perkoff was L.A.’s Ginsberg, John Harris our Ferlinghetti, and Lawrence Lipton published The Holy Barbarian in 1959, all about the Venice beat scene.

According to Lipton, the counter culture was born because of him.

Lipton became a columnist in Art Kunkin’s Los Angeles Free Press, from which flowed the counter culture of the ’60s. In 1965 Tom Wolfe wrote The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby about Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, who left the San Francisco in a surreal 1965 scene at the Longshoreman’s Hall. The story was told by Tom Wolfe but it all came from Norman Hartweg, a very early pioneer of the underground press movement in Los Angeles in the early 60s. Out of the Los Angeles Free Press came Charles Bukowski, whose columns were first published in 1969 in Notes Of A Dirty Old Man. Post Office came next, in 1971. Then there was Aldous Huxley who published his notorious Doors of Perceptionn in 1954, which paved the way for Timothy Leary and others of the drug part of the counter culture. Ape & Essence had come earlier, in 1947, creating one of the most unsettling portraits of Los Angeles ever written. In the early ’70s a Chicano writer emerged–Oscar Zeta Acosta, who published The Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo in 1972 before disappearing into Mexico like B. Traven. He was featured as “The Samoan” in Hunter Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Most of the literature of Los Angeles came out of the bohemian and apocalyptical tradition. There were anomalies, of course. Robinson Jeffers, one of Occidental College’s two most famous graduates (Barack Obama being the other) grew up in Los Angeles before moving to Carmel and writing such great poems as “Ron Stallion,” “Tamar,” “Give Your Heart to the Hawks,” “Thurso’s Landing” and “Cawdor” in the 30s. You might say Jeffers was neither bohemian or apocalyptical, although he hung around with many bohemians. His writing could possibly be labeled classical.

Still, in the early 60s, the Sierra Club and Ballantine books teamed up to produced Not Man Apart, a line from one of Jefferson’s poems, with photographs by Edward Weston–that said a lot about the age and time. Perhaps all said and done, his was and might remain the final word. A classical approach.

Lionel is the author of the classic “Literary L.A.,” available on Amazon’s Kindle Store, and a movie “Literary L.A.” is due for release in 2014.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.