THE MYSTIFYING NINE LIVES OF WRITER JERZY KOSINSKI

By Bob Vickrey

A restless publishing conference crowd appeared slightly impatient as it awaited the arrival of acclaimed novelist Jerzy Kosinski for his scheduled luncheon speech at the Copley Plaza Hotel in Boston. Kosinski was running noticeably late for an appearance that would officially launch his forthcoming book later that year.

When he finally arrived at the semi-annual Houghton Mifflin sales conference, he emerged visibly shaken, and was steadied by a company publicist. As he wiped his forehead with a handkerchief, he described an incident that had just happened on the sidewalk outside the hotel entrance. Kosinski said a plate glass window which was being installed in a nearby office tower had fallen and barely missed hitting him as it shattered on the concrete sidewalk directly in his path to the hotel.

When he composed himself and began his prepared remarks, he told the story of another potentially fatal event which happened to him in 1969. He was on the way to Los Angeles from Paris to visit his friend and fellow Polish countryman Roman Polanski, but during his New York stop-over, he discovered his baggage had been lost in route. The overnight delay in New York ultimately prevented Kosinski from accompanying Polanski to actress Sharon Tate’s house the night she was murdered by the Charles Manson followers.

Those two incidents each represented a microcosm of Kosinski’s tumultuous life in a nutshell. The turmoil began early in Poland as a childhood survivor of the Holocaust and his ongoing dance with fate continued until his untimely death in 1991.

His career was marked by controversy even as he gained international fame as a writer. His 1965 novel “The Painted Bird” was the fictional account of a young boy who wanders as a refugee across Eastern Europe during World War II and survives the cruelty and torture of those who offer him sanctuary.

The book was banned in Poland because it was regarded as being anti-Polish by the then-Communist party. It initially received a warm welcome by most critics in the American press, including excellent reviews in The New York Times Book Review and Harper’s Magazine. However, his critics would later accuse him of waffling about whether his story was an autobiographical account, or one of true fiction. He never publicly claimed the book was based on his childhood experiences, but he did little to disavow the story either—even with his editor at Houghton Mifflin. There were several assertions of plagiarism made against him. In 1982, the Village Voice claimed that “The Painted Bird” had been ghost-written by assistant editors. Kosinski countered each allegation with articles written in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times.

He won a National Book Award in 1968 for “Steps,” a collection of interconnected stories, and followed up with his novel “Being There” in 1971, which was later turned into an award-winning movie starring Peter Sellers.

Despite all the allegations against him, Kosinski became a popular figure in this country with his numerous appearances on the Tonight Show and the Dick Cavett show. Johnny Carson occasionally introduced him by acknowledging that Kosinski was quirky and unpredictable and was one of his favorite guests on the show. Once when Carson called the author’s stories “bizarre,” Kosinski quickly countered by saying, “I write about everyday life, Johnny.”

Kosinski even tried his hand in the film business when he co-wrote the screenplay for “Being There.” He had several acting roles, but his most memorable was his role as a Bolshevik revolutionary in Warren Beatty’s film “Reds” in 1981. Time and Newsweek magazine gave him good reviews in his role as American activist John Reed’s Soviet nemesis.

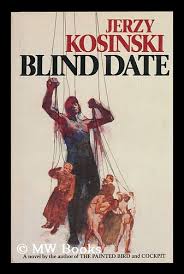

Meanwhile, after Kosinski’s stirring conference speech concluded in Boston, the company’s marketing team finalized plans for the promotional tour for his new book “Blind Date,” which would be published later that same year. Houston was one of the stops chosen for the tour, which meant I would be afforded the opportunity of accompanying him during his media and bookstore appearances there. I was the Texas sales representative for the company at the time, and escorting visiting authors about town was considered one of the true perks of my job.

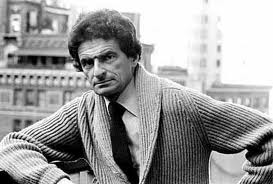

When I picked up Kosinski at the airport later that fall, I was immediately taken aback by his dramatic facial features and his intense demeanor. His dark, deep-set eyes lent a mysterious quality to his face, and his thin prominent nose added even more intrigue to the image of the man who had lived such a dramatic and seemingly tormented life.

We barely had enough time to load his baggage into my car and exit the airport before he asked if I knew of any local polo fields in the area. He had developed a great love for the game as a player and fan of the sport. Sure enough, the following day we attended a local match played in a scenic wooded area of Houston where I detected the first signs of relaxation and tranquility in him. He seemed to have found the only peaceful spot that offered a respite from his often chaotic public life. He eventually wrote the novel “Passion Play” using a polo backdrop to his story.

I had set up several bookstore appearances in the area, but there was one in particular in which I was confident he would find a smart and appreciative audience. The owner of Brazos Bookstore in the West University area was a big fan of Kosinski’s works, so I planned a dinner with Karl and his staff members after the event concluded.

As the author and I approached the store that evening and began searching for a parking spot, he glanced at his watch and asked why we were arriving precisely on time. (I naively thought this was a good thing.) He requested that we take our time and tour the area for a while longer to allow a larger crowd to assemble in hopes of building the anticipation for his arrival. We entered the front door more than twenty minutes late, and the guests who packed the store stood in unison cheering Kosinski. The man obviously knew about making dramatic entrances, which made me recall his delayed Copley Plaza Hotel arrival in Boston. (That evening’s bookstore ploy suddenly made me question the authenticity of the shattered plate-glass window story.)

At dinner that evening, I knew the bookstore staff members had come armed with a plethora of questions for the celebrated writer, but Kosinski began telling stories the minute we arrived at the restaurant and continued virtually uninterrupted for almost three hours as we sat spellbound.

I awoke the following morning to find a message from Karl thanking me profusely for setting up the dinner and calling it one of the most memorable evenings of his life.

I made no lasting connection with Kosinski during our time spent together in Houston that year. Nevertheless, I shared Karl’s enthusiasm about the mysterious and enigmatic writer who simply loved an eager and attentive audience that would listen to his stories.

Jerzy Kosinski committed suicide in May of 1991 after suffering from multiple illnesses, including heart problems, as well as severe physical and mental exhaustion. His good friend Zbigniew Brzezinski was convinced the ongoing swirling controversy about his work contributed to his death.

He invited controversy throughout his public life and seemed to often thrive on it, but perhaps Brzezinski was right; it ultimately may have taken its toll on him. All I know is that Kosinski was the most fascinating personality I have ever known, and whether his stories were true or not, remains an unimportant sidelight to me. He was simply the greatest storyteller I have ever met.

Bob Vickrey’s columns appear in several Southwestern newspapers including the Houston Chronicle and the Ft. Worth Star-Telegram. He is a member of the Board of Contributors for the Waco Tribune-Herald. He lives in Pacific Palisades, California.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.