The Memorable Life of Edith Nesbit

A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit, 1858-1924 by Julia Briggs (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1987).

By Leslie Evans

Preeminent Edwardian children’s author, prolific novelist and poet, co-founder of the Fabian socialists, friend of George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Annie Besant, Lord Dunsany, and Noel Coward, Edith Nesbit was to the world at large a figure of conventional if progressive sensibilities. In the relative privacy of her home she was the Bohemian duchess, chain-smoking mother to five children, two of them secretly by her ever-philandering husband’s live-in mistress, searcher for occult mysteries, lover of George Bernard Shaw – and afterward of an ever-younger string of adoring young men. A mesmerizing contrast of apparent acquiescence in the rigid conventionalities of late Victorian and Edwardian England, and quiet moral revolt against them.

I first encountered E. Nesbit, as she signed herself, when I was about twelve. I had been reprimanded by an officious librarian at the old Felipe De Neve branch library in Lafayette Park for trying to take out an adult book and was restricted to the children’s section. I had worked my way through the Grimm Brothers, Hans Christian Anderson’s often creepy tales, and Andrew Lang’s Blue, Yellow, Green, Orange, and etc. Fairy Books. I much preferred the more contemporary, you-can-get-there-from-here, ones: the Doctor Doolittle series; Freddy the talking pig from Bean Farm in upstate New York; and the Oz books, which the library refused to carry and I had to buy one at a time from a used bookstore on Seventh Street across Alvarado from MacArthur Park.

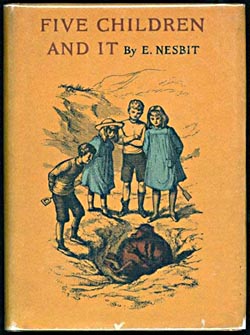

And then there were the two odd books by E. Nesbit, Five Children and It (1902) and The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904). In the first, the five brothers and sisters, in the illustrations the boys in knee britches and the girls in loose old-fashioned dresses, move from London to the countryside in Kent. Exploring a gravel pit they unearth the It, a Psammead, an ugly sand fairy, with a small round furry body and eyes on stalks like a snail, so it can hide in the sand and poke its periscope eyes up for a look. The children call it Sammyadd and find it can grant one wish every day, though the wishes expire each nightfall. The story was quaint, the children speaking in the kind of formal way that one would suppose well brought up Edwardian children would do. And unlike most of the you-can-get-there-from-here books, like Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, or the Oz books, the children don’t get to fly off to the magic country for long stays. Instead they are never far from their controlling parents for more than a few hours, forever having to hide what they are up to and living always under the adults’ thumbs.

And then there were the two odd books by E. Nesbit, Five Children and It (1902) and The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904). In the first, the five brothers and sisters, in the illustrations the boys in knee britches and the girls in loose old-fashioned dresses, move from London to the countryside in Kent. Exploring a gravel pit they unearth the It, a Psammead, an ugly sand fairy, with a small round furry body and eyes on stalks like a snail, so it can hide in the sand and poke its periscope eyes up for a look. The children call it Sammyadd and find it can grant one wish every day, though the wishes expire each nightfall. The story was quaint, the children speaking in the kind of formal way that one would suppose well brought up Edwardian children would do. And unlike most of the you-can-get-there-from-here books, like Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, or the Oz books, the children don’t get to fly off to the magic country for long stays. Instead they are never far from their controlling parents for more than a few hours, forever having to hide what they are up to and living always under the adults’ thumbs.

None of their wishes turn out very well. Riches prove to be a heap of gold coins that adults refuse to cash when presented at stores by children. Becoming beautiful only means being turned away at their home’s door when they are not recognized. Yet this is not quite the old sausage-on-the-nose three wishes that go bad, where the last wish must be used to undo the second one. In that classic fable the fault lies with the stupidity of the wishers. In E. Nesbit the children are smart enough; they are just not free enough.

In The Phoenix and the Carpet a used rug bought for the children’s nursery turns out to have a large egg wrapped within it. This hatches into an ancient phoenix, a narcissistic and imperious creature. The carpet itself is magic and takes the children on many brief adventures: to a remote island, to India, to Persia where they bring back 199 Persian cats, to France, where they give a treasure to a poor family. The phoenix demands to be taken to a temple in its honor, which it is certain from self-importance must exist. The children in a hilarious scene take the bird to the Phoenix Fire Insurance Company with results you may imagine.

Throughout the children are realistic. They quarrel among themselves, perceive the world as real children would. Their homes are middle class, but in straightened circumstances. I found something memorable about the intrusion of magic into this otherwise staid and old-fashioned England.

This was the sum of my encounter with E. Nesbit for the next fifty years. Then in the early naughts I “read” four more of her books: The Enchanted Castle, The Magic City, The Magic World short story collection, and one of Nesbit’s adult works, Man and Maid. I say “read” as much of E. Nesbit’s work has been digitized and is available for free from the Project Gutenberg text archive and other such sources. I had my computer read these to an MP3 file and listened to them on my iPod. You are probably imagining Robbie the Robot, but in fact computerized voices have improved considerably in the last twenty years. Here is a sample from The Enchanted Castle. The boy Gerald is frightened when the stone dinosaurs in the castle garden come to life. This image is from an experience in Edith Nesbit’s own childhood when she was taken to the Crystal Palace exhibit in London and crept inside the hollow innards of one of the stone dinosaurs in the courtyard.

Becoming curious I next came on a 1965 piece on Nesbit by Gore Vidal. Unstinting in his praise, he declared her, next to Lewis Carroll, “the best of the English fabulists who wrote about children (neither wrote for children).” He comments, following a then-recent critical work on her writing by Noel Streatfeild, that “E. Nesbit did not particularly like children, which may explain why the ones that she created in her books are so entirely human. They are intelligent, vain, aggressive, humorous, witty, cruel, compassionate…in fact, they are like adults, except for one difference.” The difference is that they are utterly powerless and controlled by their adult relatives.

Unhappily she was and is little read in the United States. Vidal attributes that to a tradition of narrow utilitarianism of American literary tastes in children’s books then prevailing, which kept even the Oz books out of most public libraries for more than half a century. The vogue for realistic, “practical” literature was still riding high when Vidal penned his essay. By the time the tide shifted and the era of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and lesser series such as Philip Pulman’s His Dark Materials and Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising came on the scene, too many years had slipped by for E. Nesbit’s work to benefit.

There have been two full-length biographies, E. Nesbit by Doris Langley Moore (1933), and Julia Briggs’ excellent and more extensive A Woman of Passion: The Life of E. Nesbit, 1858-1924. Langley Moore presented Nesbit as the long-suffering victim of her womanizing husband, Hubert Bland. Briggs, writing fifty years later, tells us that Edith got her own back, taking lovers as she pleased despite the hostile conventions of Victorian, Edwardian, and Georgian England.

Edith was born in South London on August 15, 1858. Her parents, Sarah and John Collis Nesbit, ran a small agricultural college on the property. She was the youngest of the couple’s four children, two brothers and a sister, as well as an older half-sister from Sarah’s first marriage. Her father died when she was four. In 1866 her older sister, Mary, was diagnosed with consumption and her mother entered on a lengthy period of abrupt relocations to try to save the child’s life. Edith was often packed off to boarding schools or to stay with distant relatives. In September 1867 the family moved to France to escape England’s damp climate. They stayed at spas in the Pyrenees, returned to England, moved to Dinan in French Brittany, sent Edith and her brothers to schools in Germany, and finally returned to London, where Mary died in November 1871 at the age of nineteen. Mrs. Nesbit then moved the family to the village of Halstead in her home county of Kent. This lasted until 1875, when whatever money they were living on ran out and they moved back to London in very reduced circumstances.

Hubert Bland Prevaricates

The story gets more interesting when, in 1877, at nineteen, Edith meets Hubert Bland, a twenty-two-year-old bank clerk. They were engaged the following year. Bland passed himself off as related to landed gentry, but Briggs describes him as “pure Cockney.” He lived with his widowed mother on the outskirts of Blackheath. Bland was already a political radical, having a nodding acquaintance with Eleanor Marx, Karl Marx’s daughter, and Henry Hyndman, head of the Social Democratic Federation. He was also a cocksman of a high order. In later life Bland claimed to have first been engaged to be married at the age of twelve. At the least, at the time he became engaged to Edith Nesbit he had just gotten his mother’s paid companion, Maggie Doran, pregnant. She bore him a son.

Edith’s poems seem to indicate that she had sex with Bland in the summer of 1879. He was still postponing the promised marriage. In the meantime, Bland kept his engagement to Edith a secret both from his mother and from Maggie Doran. Edith nevertheless moved out of her mother’s home and took rooms under the name Mrs. Bland. As for Hubert, he was spending four nights a week with Edith and the other three at his mother’s, where he could be with Maggie, neither woman knowing about the other. Hubert continued the arrangement with Maggie long after Edith found out about it, at his mother’s home until she died, in 1893, and for five years more elsewhere.

Edith, living alone and without aid from Hubert, struggled to make a living, selling her poetry to small magazines. Bland finally married her, seven months pregnant with their first child, Paul, in April 1880. Hubert did not move in with her but continued to live primarily with his mother.

Bland started a brush-making business, which quickly failed. Edith added short stories and home-made greeting cards to her output. Their second child, Iris, was born in December 1881. Around that time Edith finally found out about Maggie Doran and her child by Hubert, and Hubert told his mother about his marriage to Edith and of their two children. Hubert began to collaborate with Edith on her short stories.

The Fabian Society

Fabian socialism, named from the Fabian Society, became in Britain in later years the epitome of democratic, gradualist social reform, instrumental in winning the minimum wage and universal health care. The Fabian Society was founded on January 4, 1884, with a membership of fourteen. Hubert Bland chaired the founding meeting. He, along with Frank Podmore and Frederick Keddell, were chosen as the group’s executive committee, with Bland as treasurer. Hubert held both posts until 1911. Podmore proposed the name, for the Roman general Fabius Maximus, nicknamed Cunctator, the delayer, for his strategy of avoiding head-on battles with the Carthaginian invader Hannibal, and by extension the strategy for bringing socialism to Britain in incremental stages. The Fabians played an important part in founding the Labour Party in 1900 and remain influential in the party. A number of Labour prime ministers have been members.

Edith was elected to the Fabian Pamphlets Committee, and soon she and Hubert were the co-editors of the society’s journal, To-Day. The young George Bernard Shaw joined in September 1884. Other prominent early members included Edward Pease, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst, H. G. Wells, Oliver Lodge, and the prolific Sydney and Beatrice Webb.

Edith had a third child, in January 1885. She named him Fabian.

Years later, in 1908, the Fabian Society published a book of Edith’s socialist verse under the title Ballads and Lyrics of Socialism. Part of a poem titled “London’s Voices” captures her feelings on the injustice and inequality of her society:

’Here, in the city, Gold has trampled Good.

Come thou, do battle till this strife shall cease!’

I left the mill, the meadows and the trees,

And came to do the little best I could

For these, God’s poor; and, oh, my God, I would

I had a thousand lives to give for these!

What can one hand do ’gainst a world of wrong?

Yet, when the voice said, ‘Come!’ how could I stay?

The foe is mighty, and the battle long

(And love is sweet, and there are flowers in May),

And Good seems weak, and Gold is very strong;

But, while these fight, I dare not turn away.

George Bernard Shaw, a bit more self-distancing, in an address to the Society in 1892 spoke of its state in 1885:

“[W]e denounced the capitalists as thieves . . . and, among ourselves, talked revolution, anarchism . . . and all the rest of it, on the tacit assumption that the object of our campaign, with its watchwords, ‘Educate, Agitate, Organize,’ was to bring about a tremendous smash-up of existing society, to be succeeded by complete Socialism. And this meant that we had no true practical understanding either of existing society or Socialism.” (The Fabian Society: Its Early History, by G. Bernard Shaw, London: The Fabian Society, 1892)

By 1886 the group had grown to sixty-seven members.

Shaw and Edith

Though they had attended the same socialist meetings since early in 1884, George Bernard Shaw and Edith first seriously noticed each other at a gathering at the home of Karl Marx’s daughter Eleanor in March 1885. Edith, in a letter to her friend Ada Breakell that summer described Shaw as “one of the most fascinating men I ever met.”

Biographer Julia Briggs, who has dug through their diaries, letters, and manuscripts, writes that they had a passionate love affair between June and September 1886. Shaw turned thirty that summer, Edith twenty-eight. They went on long walks in the country, attended concerts and museum exhibits, he took her frequently back to his rooms — Shaw, like Bland a few years earlier, still lived with his mother.

Their affair was a major life event for Edith. But while it is very likely, it is not certain that it was physically consummated. This stemmed from Shaw’s ambivalence about sex. Briggs comments that “At this stage of his life, Shaw was constantly playing with the idea of marriage, and proposing to any young women whom he felt confident would refuse him, while fleeing headlong from those who showed any interest in the idea.”

Further, Shaw believed it was undignified for a man to pursue a woman, although he frequently did so. In later years he was anxious to portray the affair as largely Edith’s obsession with him. Their many secret trysts, from his diary plainly at his initiative and expense, belie this.

Briggs writes:

“Edith had fallen in love for the second time in her life with a philanderer as compulsive, in his own curious way, as Bland, even though his anxieties and inhibitions made him sexually undemanding. The experience was to be a searing one.”

And:

“Edith’s passion for Shaw was intense. At one time she proposed leaving Hubert in order to run away with him, as he privately boasted to Doris Langley Moore.” This exchange took place in 1931 when Moore interviewed Shaw for her biography of Edith.

It would seem that the affair in 1886 was not a fully conventional one. There was something in the acerbic future playwright that was more than shy about sex. When he did finally marry, to Charlotte Payne-Townsend, in 1898, their forty-five-year marriage was never consummated, ostensibly out of her refusal to have children. A 1996 book, Bernard Shaw: The Ascent of the Superman by Sally Peters, proposes that Shaw was a repressed homosexual.

Socialism and the Paranormal

The Blands, Edith more than Hubert, were interested in psychic phenomena and the esoteric as well as in socialism. This may seem incongruous in light of post-Lenin Marxism’s narrow philosophic materialism and rejection of the occult as rank superstition. In late nineteenth century England, however, while there were some hard materialists, socialism and psychic phenomena were two mutually intertwined threads of the avant garde rejection of conventional politics and conventional religion.

Briggs is not much interested in this second thread and she refers to it only in passing. In mentioning Edith and Hubert’s activities in 1885 other than the Fabian she notes their attendance at the Browning and Shelley Societies, but also “societies for psychic research.” Briggs quotes a March 1884 letter from Edith to Ada Breakell listing several books she is reading. These include, Edith writes, “an intensely interesting book which Harry [her brother, married to Ada Breakell] would like called Esoteric Buddhism by Sinnett.”

A. P. Sinnett was a recently converted disciple of the Russian mystic Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the founder of the occult Theosophical Society. Sinnett’s book had little to do with any recognized school of Buddhism but was devoted to Blavatsky’s schema of world evolution from the mythical continents of Lemuria and Atlantis, and the teachings of her claimed Mahatmas or Ascended Masters of Tibet, essentially all-wise spirit guides who live on the Astral Plane and from there influence the course of human history. Sinnett was the recipient of a series of alleged letters from the Mahatmas, the question of their authenticity raising a heated controversy even in circles sympathetic to the idea of spirit communication.

These could have been casual interests on Edith’s part, but Alex Owen, in The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern, reports that Edith Bland was also an initiate of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the preeminent occult organization of its day, and one requiring a demanding admission process. The Golden Dawn was famous for teaching the practice of magic. Its best-known members were the famed Irish poet William Butler Yeats, Irish socialist actress Florence Farr, Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne, and the infamous “black magician” Aleister Crowley.

Alex Owen offers an explanation of the affinity between political radicalism and the occult. The late nineteenth century was an age in which the rapid changes caused by industrialization and urbanism, the expansion and secularization of education, led to widespread questioning of the whole gamut of traditional values. Socialism was the defense of the oppressed poor against the indifference or worse of the dominant Conservative and Liberal parties. Spiritualist mediums, and the more academic and credentialed Society for Psychical Research, proposed and carried out empirical research into the claims of traditional scriptural religion that there was some kind of afterlife. Both currents were looked on in their day as the epitome of modernism.

Further, both the socialist organizations and the occult ones welcomed women into positions of leadership which were essentially closed to them in Victorian and Edwardian England. A good example was Anna Bonus Kingsford (1846-1888), only the second English woman to get a medical degree, a militant animal rights advocate and anti-vivisectionist who managed to get through medical school while refusing to dissect a living animal. She was both a prominent women’s rights campaigner and at the same time rose to head Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society, where she claimed to get insights in trance states from nonmaterial beings.

Still more famous was Annie Besant (1847-1933), an early leader of the Fabian Society, a close friend of Edith Nesbit, and eventually also president of the Theosophical Society. Besant lost custody of her children in a famous court case because of her advocacy of birth control. In her socialist period she was a principal speaker at the November 13, 1887, rally in Trafalgar Square attacked by troops and remembered as Bloody Sunday. She was a leader of the London matchgirls strike of 1888. The girls worked a fourteen-hour day for pitiful wages. The phosphorus used in making matches was also used in rat poison and caused extensive liver and kidney damage. George Bernard Shaw and Hubert Bland raised money for the match strikers, which they distributed at the factory gates as strike pay.

During the 1880s Besant spent much time with Edith Bland and even took the two older children, Paul and Iris, home with her when Edith came down with the measles. Besant also, incidentally, fell in love with George Bernard Shaw. She proposed that he come live with her, but he refused.

She was won over to Theosophy in 1890, moved to India, where she claimed to have become a clairvoyant, and rose to head the organization which by then was international in scope. Her new associates were now people like Colonel Henry Steel Olcott and Charles Leadbeater, names to conjure with in the occult fraternity. Olcott had earned his military title in the American Civil War and had served on the official investigating commission into the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Nor was this mixing of socialist politics with the occult just a female proclivity. Two of the central founders of the Fabian Society were Edward Pease and Frank Podmore (1856-1910). Podmore’s home was also for years the Fabian office. In his The History of the Fabian Society Pease describes how he and Podmore got the idea for the group:

“In the autumn of 1883 Thomas Davidson paid a short visit to London and held several little meetings of young people . . . I attended the last of these meetings held in a bare room somewhere in Chelsea, on the invitation of Frank Podmore, whose acquaintance I had made a short time previously. We had become friends through a common interest first in Spiritualism and subsequently in Psychical Research, and it was whilst vainly watching for a ghost in a haunted house at Notting Hill – the house was unoccupied: we had obtained the key from the agent, left the door unlatched, and returned late at night in the foolish hope that we might perceive something abnormal – that he first discussed with me the teachings of Henry George in ‘Progress and Poverty,’ and we found a common interest in social as well as psychical progress.”

Frank Podmore is remembered as much for his books on psychic phenomena as for his role among the Fabian socialists. These include Phantasms of the Living (1886, coauthored by Frederick Myers and Edmund Gurney); Studies in Psychical Research (1897); Modern Spiritualism (1902); and The Newer Spiritualism (1910).

Oliver Lodge, mainly known as a physicist, was a long-time Fabian, author of two Fabian tracts and co-author of a third with Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw, and Sidney Ball. At the same time he conducted studies of telepathy in the 1880s and served as president of the Society for Psychical Research from 1901 to 1903.

Little Orphan Alice’s Come to Our House

Edith made friends readily and always had an admiring circle of both men and women. Among her women friends the closest included Ada Breakell, who married Edith’s brother Harry and moved with him to Australia, and Alice Hoatson. Edith first met Alice in January 1882 when Alice was working as reader for Sylvia’s Home Journal and Edith visited their offices to try to submit a short story. Alice was six months younger, from Yorkshire. They were temperamentally opposites, Edith outgoing, strong-willed, prone to emotional extremes, overflowing with literary and other projects; Alice quiet, submissive, efficient, and home centered.

Alice was ineluctably drawn into the Blands’ lives. She became Edith’s most frequent companion. In 1884 she joined the Fabian Society where she became the organization’s assistant secretary. Edith even urged Alice to distract Hubert’s attention from his latest lover. Alice, who the Blands nicknamed the Mouse – they called each other Cat, which tells much – succeeded too well. The cat caught the mouse and she was soon pregnant with Hubert’s child. Edith had for several years urged Alice to come and live with them. She finally did so in late 1886, where she discreetely gave birth to Rosamund that November.

Victoria was still on the English throne. Had their domestic situation become public it could have destroyed the Blands still very marginal literary careers, on which their precarious livelihoods depended. Edith and Alice agreed that Edith would claim to be the mother. They maintained this fiction throughout their lives, repeating the ruse thirteen years later when Alice bore Hubert a second child.

Of course their close friends knew of the subterfuge. And there was always Maggie Duran, the mother of Hubert’s other out-of-wedlock child. Even she joined the Fabian Society, in 1890, where that secret slipped out as well.

George Bernard Shaw’s biographer described Hubert, as Shaw viewed him, as “a Tory Democrat from Blackheath, who sported fashionable clothes, wore a monocle, and maintained simultaneously three wives, all of whom bore him children. Two of the wives lived in the same house. The legitimate one was E. Nesbit.” (cited by Briggs, p. 108)

The disparaging “Tory Democrat” reflected much that was conservative in Hubert Bland’s outlook despite his socialist politics. Most notably he was firmly opposed to women’s suffrage. He is said to have exclaimed, “Votes for women? Votes for children! Votes for dogs!” Edith under pressure from Hubert also opposed women’s suffrage, arguing rather tendentiously that it would set back the movement for socialism by flooding elections with votes by Conservative women.

Julia Briggs describes the Bland menage of those years:

“Alice was socially unassertive, which allowed Edith to shine unchallenged; she was also capable and dependable, quite content to play ‘the humble satellite to a comet’, as she herself put it. She relieved Edith of organizing or undertaking the dull routine household tasks, and dealt more effectively and consistently with the servants, her steady temperament acting as a foil to Edith’s volatile nature.”

Literature and Lovers

Edith Nesbit would be past forty before she wrote the children’s classics on which her reputation rests, as well as many adult novels and short story collections. In the penurious eighties she survived by hand painting and writing poems on greeting cards, and publishing an occasional poem or short story in various magazines and newspapers. Briggs writes: “She would allow the butcher’s and baker’s bills to mount up to huge sums, and would then write some verses or stories to pay them off. She liked this functional way of thinking about her work so that each piece of writing was destined to pay off some particular household bill.”

Hubert never made much of a living. For a few years he had a job with the Hydraulic Power Company, and when he lost that, turned to journalism. He and Edith in the early years collaborated using the pen name Fabian Bland, under which they published a novel, The Prophet’s Mantle, in 1885.

In her own name Edith concentrated on poetry, which she always believed was her true gift. She published three slim volumes of her poems in 1885. Then, in 1886, Longmans published her Lays and Legends. It had been recommended by their reader, prominent author Andrew Lang, who coincidentally is also best remembered for his children’s books, of traditional fairy stories. The poems were praised by the widely popular poet Algernon Swinburne as well as by adventure novelist H. Rider Haggard. Oscar Wilde sent her an encouraging letter.

As she neared thirty Edith also began to take lovers, generally younger men from her circle of admirers among the Fabians. The first was Noel Griffith, studying to be an accountant, twenty-three to her twenty-nine.

In the early nineties she began a long affair with Richard le Gallienne (1866-1947), a slim, elegant, and prolific poet, possibly best remembered for his novel Quest of the Golden Girl. George Bernard Shaw wrote an extremely hostile review of le Gallienne’s English Poems (1892), probably because many of them were thinly disguised love poems to Edith Bland. At one point Edith wanted to run away with le Gallienne but was persuaded against it by Alice Hoatson. The affair continued after le Gallienne married Mildred Lee in 1891, and was the source of much guilt when Mildred died young in 1894. In 1903 le Gallienne moved to the United States. There his esthete taste and archly traditional romanticism found little resonance and he never achieved the popularity he had in fin de siecle England. Still, I have long enjoyed le Gallienne’s October Vagabonds, a luminous account of his attempt, accompanied by a French artist, to walk four hundred and thirty miles from upstate New York to Manhattan.

Maturity and Success

As she aged, Edith drew around her an ever younger group of admiring young men. One of these, Oswald Barron (1868-1939) became her lover and her muse. A Fabian, a columnist for the London Evening News under the pen name the Londoner, Barron was more than anything else a scholar of medieval heraldry and noble genealogies. They wrote poems and short stories together, Barron proving to be an endless font of plot ideas. More than that, he imbued Edith with a sense of the importance of history and of the recollections of childhood. This transformed her writing and in the process won her a mass audience for the first time.

Her breakthrough book was The Story of the Treasure Seekers (1899), the first of a series of semi-comic novels about the Bastable children. Their names were taken from her coterie of young Fabian men, the hero being Oswald Bastable after Barron, though the children’s personalities were modeled on Edith’s brothers and sister. It was an immediate best seller. The self-important Oswald recounts in somewhat inflated style how he and his five brothers and sisters try many different ways to find some treasure after their mother has died and their father has been slipping into penury. There were two sequels, The Wouldbegoods in 1901, her most successful book, and The New Treasure Seekers in 1904. All remain in print a century later, the first of the Bastable books having been three times made into a television series and once into a TV movie.

Hubert’s fortunes also improved. He was now doing book reviews for the Daily Chronicle and a popular column for the Manchester Sunday Chronicle that at its height claimed a million readers. The Blands had lived in numerous houses during their marriage. Now finally prosperous, they rented Well Hall in Eltham, on the border between Kent and London. This was a decayed eighteenth century mansion of thirty rooms. It stood on the grounds of a still earlier house built by Sir Thomas More, Henry VIII’s martyred chancellor, for his daughter. She was said to have brought his severed head there for burial after the king had him executed for opposing Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn. The deep moat that had surrounded the original house was still intact in the back grounds when the Blands lived there. Edith did much of her writing in a rowboat on the water.

The old mansion was as dilapidated as the place Tom Hanks buys in the film The Money Pit. The main staircase suddenly collapsed, the gutters failed and the ground floor was flooded. Edith claimed the house was haunted by a ghost that played the piano when no one was in the room, and stood behind her when she was writing, quietly sighing. She began to gain weight, and chain smoked her hand-rolled cigarettes. The household was gregarious and saw many guests, parties, and lectures. Edith was especially fond of parlor games, skits, charades, and musical evenings.

Her initial literary successes were all in naturalistic settings, the fantasy works would come later. In both, however, she refuses to idealize her child characters or their powers. Her biographer writes:

“Over and over again Edith presents her child protagonists in unmanageable confrontation with irate adults whom they are quite unable to cope with. She is realistically aware of the child’s lack of any real power other than the power of imagination . . . . It is her refusal to idealize either the child’s actual – as opposed to imaginative – power, or the nature of the world that children inhabit that constitutes E. Nesbit’s great strength and perhaps her most important contribution to children’s fiction.”

Edith had three living children – Paul, Iris, and Fabian – but afterward she gave birth twice to babies that were still-born. She took these very hard, the blows magnified as Alice Hoatson gave birth in close proximity each time to a healthy child of Hubert’s. The first dead baby was in April 1886 followed by the birth of Alice’s Rosamund in November, when Alice joined the Bland household. This sequence was repeated in 1899, shortly after the move to Well Hall, when Edith bore a second dead child, and Alice gave birth to John Oliver Wentworth Bland. Edith, as she had done with Rosamund, adopted John and presented him to the world as hers while Alice continued to play the role of the spinster Auntie.

The following year Edith’s youngest, Fabian, died, at fifteen, from a botched anesthesia during a routine operation conducted at Well Hall to remove his adenoids. No one had thought to tell him not to eat the night before the surgery and he asphyxiated in his vomit while no one was watching him. The family was devastated.

Edith’s turn to fantasy and magic was linked to the appearance of The Strand magazine in January 1891. Best known as the place where Sherlock Holmes pursued his trade, The Strand built a stable of well-known authors, besides Conan Doyle including Rudyard Kipling, H. G. Wells, E. W. Hornung (Doyle’s brother-in-law, who wrote the Raffles the Gentleman Burglar series), and Max Beerbohm. The magazine strongly preferred fantasy. Edith published her first fantasy book, Five Children and It, serially in The Strand in 1901. The two sequels in the Psammead series, The Phoenix and the Carpet and The Story of the Amulet followed in 1904 and 1906, then her two related time travel books, The House of Arden and Harding’s Luck in 1908 and 1909. All the rest of her fantasy and magic books, such as The Enchanted Castle, The Magic City, and finally Wet Magic, about children who find a mermaid, also appeared first in The Strand. While the children in the Bastable books were modeled on her siblings, the fantasy book children were modeled on her own children. She also wrote eleven novels for adults between 1885 and 1922, none of which gained the audience her children’s fiction did.

G. K. Chesterton’s sister-in-law Ada, a frequent visitor at Well Hall, described Edith in her Bohemian prime:

“Mrs Bland . . . was always surrounded by adoring young men, dazzled by her vitality, amazing talent and the sheer magnificence of her appearance. She was a very tall woman, built on the grand scale, and on festive occasions wore a trailing gown of peacock blue satin with strings of beads and Indian bangles from wrist to elbow. Madame, as she was always called, smoked incessantly, and her long cigarette holder became an indissoluble part of the picture she suggested – a raffish Rossetti, with a long full throat, and dark luxuriant hair, smoothly parted. She was a wonderful woman, large hearted, amazingly unconventional, but with sudden strange reversions to ultra-respectable standards.” (cited by Briggs, p. 233)

The Blands often took in strays in need of support. Edith even welcomed Maggie Doran, the mother of Hubert’s first child, now in ill health, into her home, where she lived until her early death in 1903.

In 1907 Edith founded a short-lived literary journal, The Neolith, printed in hand-done calligraphy on oversized paper. Contributors included H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, G. K. Chesterton, Andrew Lang, and Lord Dunsany. This last, in private life better known as Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany, became one of Edith’s lifelong friends. She and Alice’s son John visited Dunsany and his wife at their ancient Dunsany Castle in Ireland in 1910. Lord Dunsany has long been one of my favorite authors, his ornate and archaic language and bizarre worlds with their own gods unlike the work of any other I can think of. Dunsany was also a playwright, a financial supporter of Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre, and a friend of W. B. Yeats and Yeats’ patron, Lady Gregory.

The H. G. Wells Fiasco

H. G. Wells and his wife Amy Catherine joined the Fabian Society in February 1903, beginning that fall to exchange regular visits with the Blands. For several years the two families were very close. Wells once showed up at Well Hall unannounced and stayed for a week, finishing his novel In the Days of the Comet in the back garden.

Distance set in during 1906 when Wells began a campaign to reorganize the Fabian Society. He demanded that it become more like a political party, adopt an official line in contrast to the wide spectrum of views currently tolerated, run candidates for parliament, and, stickiest of all, get rid of the existing Executive Committee, including Hubert Bland. There was also some suggestion in Wells’ proposals that he wanted an endorsement of free love, which horrified the Edwardian sensibilities of many members.

Bernard Shaw supported the Old Guard against Wells and the thing came to a head in a couple of large meetings in December 1906 where Wells was roundly defeated.

The rift became a chasm when, in 1908, Wells, then forty-one, tried to run away to Paris with Hubert’s beloved daughter Rosamund, twenty years his junior. The eloping couple were betrayed and Hubert caught them on a train at Paddington Station. Hubert Bland, monocle or not, was a large, powerful man and an excellent boxer. He thrashed Wells and carted his wayward daughter home. Wells in the appendix to his 1934 Experiment in Autobiography claimed that he was precipitated into adultery with Rosamund to save her from Hubert, saying that “her father’s attentions to her were becoming unfatherly. I conceived a great disapproval of incest, and an urgent desire to put Rosamund beyond its reach in the most effective manner possible, by absorbing her myself.” Such self-sacrifice!

Whatever the truth of Wells’ accusation, he lost the sympathy of the Fabians when the following year he betrayed his wife again, getting Amber Reeves, a young member of the group, pregnant. She managed a hasty marriage with someone else, but Wells persisted in the affair after the marriage. Sidney and Beatrice Webb now broke off their friendship with Wells over his conduct. Wells got even in 1910 with a roman a clef, The New Machiavelli, in which the Webbs do not fare well and the Blands appear very negatively but unmistakably as the Booles.

Edith and Shaw Late in Life

Edith Nesbit and George Bernard Shaw remained close friends for life, though they never were again lovers. As they entered middle age their interests and outlooks began to diverge, without diminishing their mutual affection. Edith, while still retaining her interest in socialism, dropped away from active participation in the Fabian. Around the time she turned fifty she became passionately absorbed by the Baconian controversy. This in its simplest form was the claim that Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was the true author of Shakespeare’s plays. That issue has sputtered on to our own day where a small group of irreconcilable conspiracy theorists still hold that Shakespeare was a village clod while Bacon wrote his plays, if not almost every other major work of Elizabethan England including the Fairy Queen.

For the more esoteric wing of the Baconian movement, the plays were only the appetizer. Just as the true alchemists of the Middle Ages regarded turning lead into gold as little more than a parlor trick on the road to discovering the Philosopher’s Stone and achieving immortality, the occult Baconians hoped through secret ciphers hidden in the plays to unravel the Rosicrucian mysteries of which they believed Bacon to have been a master, and the hidden lore of the Freemasons, in Bacon’s day a feared secret society and not yet the businessmen’s club known for its funny hats and handshakes. Edith Nesbit was more drawn to the search for mystic enlightenment in her ciphering than the question of who really wrote Hamlet.

Edith invested large amounts of time and money, trying vainly to learn logarithms in hopes of finding secret ciphers hidden in Shakespeare’s plays, buying rare books, and for years supporting an old neer-do-well known as Tanner who was said to be doing his own research on Baconian ciphers. By ciphers the devotees intended coded messages buried in the text to be extracted by discovering the pattern of the code.

Shaw at the same time was evolving in the opposite direction, toward a far harder version of socialism, and then beyond that to an admiration of all of the contemporary absolutist revolutions and their dictators of the far left and far right as superior to mere corrupt capitalist democracy. The worst of this would come in the quarter century in which he outlived her.

In the years of their friendship Shaw limited his advocacy of extremist propositions to selective human breeding according to the tenets of the Eugenics movement. He amalgamated his notion of socialism with calling for government and corporate directed breeding programs aimed at creating a race of Nietzschean supermen. This drew little adverse reaction, as he presented his view – notably in his 1901 play Man and Superman – in witty dialogue wrapped in the popular verbiage of onward and upward evolution, promotion of the Life Force, and as an egalitarian process blind to class differences.

Shaw had no patience for mysticism or the occult, though those beliefs were probably less harmful than the things he did advocate in the world of secular reality. He good naturedly lent Edith money to pursue her Baconian studies, and also his replica set of early editions of Shakespeare for her to test her cipher skills on. Still, he joked with her that he could show from textual comparisons that his own plays had all been written by Sidney Webb.

Last Years

Hubert in 1911 began to lose his eyesight. Soon he was blind. He continued to write his weekly column and do some book reviewing, Alice Hoatson reading the books to him and taking down his dictation. Edith’s creativity began to flag, and in 1913, after the serial publication of Wet Magic, the last of her children’s books, The Strand canceled her contract, leading to a drastic decline in her income. After more than a decade of prodigious literary output Edith fell silent for the next eight years, returning only a few years before her death with two adult novels. Hubert died suddenly, in April 1914.

There followed some years of financial hardship. Edith, Alice, and their children took in paying guests at Well Hall. They set up a roadside stand where they sold vegetables and flowers. For a while they raised chickens and sold the eggs, until an outbreak of disease killed the flock.

Three years after Hubert’s death Edith remarried, not to an intellectual but to Thomas Tucker, known as “the Skipper,” a marine engineer and ferry boat captain. She was defensive about his lower class bearing but they were very happy together. Alice finally left, after thirty-one years, moving to London where she worked as a nurse.

Edith’s health began to fail, as her persistent smoking produced ever more serious attacks of asthma and bronchitis. She and the Skipper had in the end to abandon Well Hall as too expensive to maintain. From the grand house they moved to a pair of brick sheds recently built by the Air Force in the village of St. Mary’s in the Marsh. The Skipper partitioned the open interiors into numerous rooms. In her last year Edith made friends with a new neighbor in the village, the young Noel Coward, who found her enchanting. He had read and collected her books as a child.

Edith died on May 4, 1924, of lung cancer. Alice Hoatson lived long enough to be interviewed by Doris Langley Moore for her 1933 biography of Edith, but to the end maintained the pretence that Rosamund and John were her niece and nephew. Paul, Edith’s first born, always ill at ease with his Bohemian family, worked in finance, married unhappily, and committed suicide at sixty in 1940. Iris became a dressmaker. Rosamund cared for Skipper in his last years and published one novel, in 1934. Of Iris, Rosamund, and John and their later lives, Julia Briggs could discover only the probable decade of their deaths.

Julia Briggs closes her biography with an appreciation of Edith’s work that Noel Coward wrote in 1956:

“I am reading again through all the dear E. Nesbits and they seem to me to be more charming and evocative than ever. It is strange that after half a century I still get so much pleasure from them. Her writing is so light and unforced, her humour is so sure and her narrative quality so strong that the stories, which I know backwards, rivet me as much now as they did when I was a little boy.”

There was a copy of The Enchanted Castle next to his bed seventeen years later when he died.