The Magic of Lord Dunsany

Leslie Evans

When the world is too much with you, the inanities of politics have you down, and the fount of insoluble crises discourages, it is a good time to read something by Lord Dunsany. An Edwardian Irish aristocrat, much of his voluminous work is long out of print, but what is available is mostly his early wonder tales, probably his best. Dunsany is usually described as a fantasy or science fiction writer, but such terms mislead. He is often compared to the more widely read H. P. Lovecraft, who readily acknowledged Dunsany’s influence, yet their work shows more differences than similarities.

I had a taste for Lovecraft in my teens, but reading him now I am put off by his sodden load of manipulative adjectives. The first page of “The Dunwich Horror” gives us “squalor,” “dilapidation,” “gnarled solitary figures,” “crumbling doorsteps,” “creepily insistent rhythms,” “rotting gambrel roofs,” “tenebrous tunnel,” “malign odour,” “stigmata of degeneracy and inbreeding,” “unhallowed rites.”

Dunsany’s style changed several times over his lifetime, but it was always clear, simple, and relatively adjective-free. His early work owed much to the King James Bible, then came a poetic period in modern prose, and in the final laps, straight story telling. Accompanying this change of style there is a migration also from imaginary cities and countries to actual places and from magical or mystical forces to the merely extremely improbable.

Where Lovecraft sought to create an atmosphere of repellent horror, Dunsany’s writing more often exudes a melancholy poetic beauty, though he delved into horror, more often when he used settings somewhere in the real world, rather than his dream lands. Their oeuvres run in parallel in their interest in strange forgotten gods, Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos and Dunsany’s gods of Pegana, but Lovecraft’s gods are always sinister, threatening to return to earth to the detriment of humanity, while the gods of Pegana are mostly far away and indifferent to humans, rather on the Gnostic model. Oddly, the Irish lord’s outlook, something of a country squire lamenting the expanding evils of the machine age and its threat of destroying both Nature and humanity, his pervading sense of the fragility of civilization, and of Time as a wrecker rather than an engine of progress, a century later can seem to merge with today’s fears of impending ecological cataclysm, though at an eerie remove. A leitmotif of his work is that humans are becoming ever more disconnected from and damaging to the natural world and in so doing both risk and deserve extinction.

There are not any individualized humans in The Gods of Pegana, Dunsany’s first book. The personifications Fate and Chance cast lots to begin the Game. We never know which won, but he chooses Mana-Yood-Sushai as his player. Mana-Yood-Sushai in turn creates the gods, among them Skarl the Drummer. As Skarl begins to drum, Mana-Yood-Sushai falls asleep, the lesser gods create the worlds, and the play begins. When Mana wakes, “the gods and the worlds shall depart, and there shall be only Mana-Yood-Sushai.”

There is creation but it doesn’t start with origins as Genesis does. The Game in which we are tiny pawns begins “Before there stood gods upon Olympus, or ever Allah was Allah” but still long after when time and space came into being:

“When Mana-Yood-Sushai had made the gods there were only the gods, and They sat in the middle of Time, for there was as much Time before them as behind them, which having no end had neither a beginning.” The gods in turn make the worlds, not for some grand purpose as the God of Genesis does but to amuse themselves. After a million years, through which Mana-Yood-Sushai slumbers, the god Kib creates the beasts of Earth to play with. After another million years “Kib grew weary of the second game, and raised his hand in The Middle of All, making the sign of Kib, and made Men: out of beasts he made them, and Earth was covered with Men.” All this time Skarl beats on his drum so that Mana-Yood-Sushai will not wake, which would destroy the gods and their plaything worlds, including us, to begin a new Game.

The Gods of Pegana was published in 1905, an intriguing vision for an Edwardian Irish lord. It contained many more tales, of the doings of Kib, the Sender of Life in All the Worlds, of Sish, the Destroyer of Hours, Slid, Whose Soul Is by the Sea, and Mung, Lord of All Deaths between Pegana and the Rim. Many lesser gods are added. And then come human prophets, powerful figures in their human communities for their supposed influence with the gods, but generally ignored by the lords of Pegana.

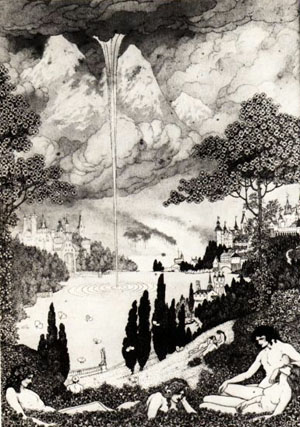

In preparing publication Dunsany enlisted Victorian-Edwardian artist Sydney Sime as his illustrator. Sime was a prominent magazine illustrator, and did drawings for other authors of fantastic and macabre literature, such as William Hope Hodgson and Arthur Machen. The collaboration lasted until Sime’s death in 1941, in most cases Sime producing drawings for Dunsany’s stories, but sometimes the reverse, with Sime submitting a set of drawings and Dunsany inventing stories to explain them.

Dunsany (pronounced Dun-SAY-nee) followed with more tales of the Pegana universe in Time and the Gods (1906), its amused tone captured in the story “The Relenting of Sarnidac.” Sarnidac is a lame dwarf shepherd boy, the butt of jokes in his home city. One day Sarnidac sees a line of tall strange figures walking southward on the dusty road. Out of curiosity he falls in behind them, marching on until they come to the neighboring city of Khamazan. There the people recognize the marchers as the gods of the Earth, but as they approach the city gates the figures begin to rise into the air, higher with each step until they are gone into the sky. The people call on the gods not to desert them, and then they are all gone except the lame dwarf who is seen to remain on the road. The lame boy is taken in triumph to occupy the king’s palace. “And the Book of the Knowledge of the Gods in Khamazan tells how the small god that pitied the world told his prophets that his name was Sarnidac and that he herded sheep, and that therefore he is called the shepherd god.”

Dunsany rarely returned to the Pegana gods. Indian-American literary critic Sunand Tryambak Joshi in his Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination, comments, “But the themes that were broached in these two books – fantasy as Nature, the glories of the unmechanized past, antihumanism, the awesomeness of Time and the power of art and dreams to combat it – would receive many distinctive variations and elaboration in his subsequent story collections, plays, novels, and poems.”

Between 1908 and 1916 Dunsany produced five slim volumes of wonder tales, his most lasting work, beginning with The Sword of Welleran. There followed stories of the world war, plays (forty-seven of them), nine novels, and in his later years, the tall tales of Jorkens the London clubman, and several books of poems. For purists, including H. P. Lovecraft, Dunsany never surpassed his early naive, childlike tales, in The Sword of Welleran (1908) and A Dreamer’s Tales (1910). His language does become flatter in the later work and an element of tongue-in-cheek creeps in already in the later of the stories in The Book of Wonder (1912). An example from this last is the opening of “The Hoard of the Gibbelins,” which Wikipedia cites as most typical of Dunsany’s prose. It does capture one side of him, when he is after a kind of ironic horror:

“The Gibbelins eat, as is well known, nothing less good than man. Their evil tower is joined to Terra Cognita, to the lands we know, by a bridge. Their hoard is beyond reason; avarice has no use for it; they have a separate cellar for emeralds and a separate cellar for sapphires; they have filled a hole with gold and dig it up when they need it. And the only use that is known for their ridiculous wealth is to attract to their larder a continual supply of food. In times of famine they have even been known to scatter rubies abroad, a little trail of them to some city of Man, and sure enough their larders would soon be full again.”

Dunsany doesn’t abandon his lovely or evil fantasy cities until his Jorkens books, and his second Irish novel, The Story of Mona Sheehy (1939).

Lord Dunsany, the scion of an ancient Irish peerage, was born in London on July 24, 1878, his proper name being Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett. Through most of his life he alternated living in England, at a small family estate called Dunstall Priory near Shoreham, Kent, and at Dunsany Castle, twenty miles northwest of Dublin. The family is said to have come from Denmark and to have settled in Ireland in the tenth century, before the Norman Conquest. They intermarried with the Cusacks, a Norman family, who built Dunsany Castle between 1180 and 1200, making it probably the oldest continually inhabited structure in Ireland. Edward inherited the title on his father’s death in 1899 and signed all of his many published works Lord Dunsany. His life is chronicled in a 1972 biography by Mark Amory. S. T. Joshi’s Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination (1995) offers a critical appreciation of his writings.

Edward attended Eton, then Sandhurst, Britain’s preeminent military academy. In 1899, at twenty, he joined the Coldstream Guards and served under fire in South Africa in the Boer War, where he was friends with Rudyard Kipling. He left the army in 1901. By this time he had acquired two of his lifelong interests: hunting and chess. He grew a deep love of nature, somehow reconciling that with all the killing he was doing, paired with a deepening abhorrence of industrial civilization. His hunting took him outdoors, where he spent endless hours in the woods, claiming he shot his own dinner from October to March. In later years he went on shooting expeditions to Africa, India, and the Middle East.

Dunsany, as he came to be known, was among the pro-British Irish. More typically these lived in Northern Ireland and were Protestant by religion. Lord Dunsany’s Irish connections were in the south and whatever his religious views he was not a Christian. S. T. Joshi calls him an atheist based on the universe depicted in The Gods of Pegana. While strange and multiple gods predominate in his fiction, and there is also a pronounced sympathy for paganism in his few Irish-themed books, there are a few stories, such as “The Kith of the Elf-Folk” and “Where the Tides Ebb and Flow,” that refer to a single god and Paradise, while “The Sailors’ Gambit” concerns a traditional pact with the Devil for a crystal that allows its users to win at chess. Even in these few stories, gods singular or multiple have no real interest in humans except occasionally to punish them for their impudence, as in his play The Gods of Mountain (1910), where a band of beggars impersonate the seven jade gods of a mountain to get the credulous villagers to bring them food and gifts. The gods retaliate by turning the imposters into jade statues, which the villagers continue to worship, quite ignorant of the real import of the transformation.

Dunsany married Lady Beatrice Villiers in September 1904, he twenty-six, she just short of twenty-four. Beatrice proved to be level headed and literate, Mark Amory relying heavily on her diaries for his biography. In August 1906 their only child, Randal, was born.

Hunting and the military were conventional activities for a landed aristocrat. Writing strange fiction was not, and it took several years before Dunsany’s reputation shifted from that of a lord who wrote on the side to a writer who also happened to be a lord. Some critics were never convinced that he was not a dilettante. Archaic as always, he did much of his writing with a quill pen on large sheets of paper in an oversized looping calligraphy, or he dictated to Beatrice, who took it down in shorthand.

As an increasingly prominent Irish writer, based at least part of the year near Dublin, he developed a prickly friendship with William Butler Yeats, though Beatrice came to dislike Yeats’s patron, Lady Gregory, accusing her of stealing Dunsany’s plots. Nevertheless, Yeats edited a collection of Dunsany’s writings that appeared in 1912.

At Yeats’s suggestion, Dunsany wrote his first play, The Glittering Gate, in 1909. Bill, a burglar, dies and finds himself facing a great golden gate, presumably the gate to heaven. His old friend Jim is there, unhappily locked out and continually opening beer cans lying on the ground, each one proving to be empty. Bill eventually goes to work on the gate with his burglar tools, forces it open only to discover empty space filled with stars.

The Irish Renaissance, or Celtic Revival, was in full swing, with authors such as W. B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, George Russell, J.M. Synge, Oliver Gogarty, and Sean O’Casey. They approached Dunsany, but he never really fit in, both because of his pro-British politics and because there was nothing Irish about his work. This distance continued for decades. In 1932 Yeats was instrumental in founding the Irish Academy of Letters, with George Bernard Shaw as its first president and Yeats as vice president. It had two classes of membership, the higher called “Academicians,” the lower, “Associates.” Academicians had to have done work “Irish in character or subject,” Associates needed only to be of Irish descent. Dunsany was furious at being offered only an Associate membership and refused. Amory records that “Dunsany . . . writing over ten years later says only that he retaliated in private with a society to honour writers of the 14th century in Italy. ‘Who, I asked, would they suggest? Dante of course was suggested; but I was shocked. “Most certainly not,” I said, stroking my hair as Yeats used to stroke his. “Dante did not write about Italy, but of a very different place. Most unsuitable.”‘ He went, however, to Yeats’ memorial service to show no animosity remained.”

The slight prompted him to write his first sustained Irish-themed piece, his novel The Curse of the Wise Woman (1933), considered one of his best works. The wise woman, Mrs. Marlin, curses a British development company that has brought earth moving equipment to drain the historic bog where she lives. A great storm of possibly supernatural origin buries their building site and saves the natural enclave. It won the Irish Academy of Letters’ Harmsworth Literary Award as best Irish novel of the year and Dunsany was elected to full membership in the Academy.

Though Dunsany knew all the major figures of the Celtic Revival, most of his close friends were Unionists. The only one of the republican writers he became really close to was Oliver Gogarty, a romantic if overly plump figure, poet, medical doctor, gossip, and militant Nationalist. Among the Dunsanys’ friends was Edith Nesbit, the English Fabian activist and children’s’ author, who was among his earliest readers. He contributed to her short-lived magazine Neolith, and on a visit to Dunsany Castle she played with him at building houses in the drawing room out of furniture and bric-a-brac, a central plot device in her 1910 The Magic City.

In early 1913 Dunsany and Beatrice went to Algeria, where he did his first big game hunting. He returned to Africa alone that fall, this time to Kenya, where he conducted a killing spree that would freeze the blood of any animal lover; fifty-five beasts including 4 warthogs, 6 zebras, 3 jackals, 8 impalas, a lion and a rhinoceros.

The heyday of his career as a dramatist ran from his 1909 Glittering Gate through the end of the Great War, with productions of such plays as King Argimenes and the Unknown Warrior (1910), Alexander (1912), The Queen’s Enemies (1913), and If (1919). The Queen’s Enemies is based on an account in Herodotus in which Egyptian Queen Nitokris invites her enemies to a banquet in an underground temple, then kills them by opening floodgates to the Nile. If is an early time travel story in which a mysterious man from the East offers the hero a crystal that allows him to go into the past to make changes in his life. It ran for two hundred performances in London in 1921-22, Dunsany’s swansong when he briefly stood in the first rank of British playwrights. His exotic locales and royal protagonists lost their savor after the war and his plays were rarely performed.

When World War I broke out in 1914 Dunsany joined the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, where he was made a captain. He was slated to be sent to Gallipoli, but against his will, probably because of his age, was transferred to a reserve unit in Derry in the north of Ireland. He was on leave at Dunsany Castle when the week-long Easter Rising broke out in April 1916, during which the Nationalists captured Dublin and held it for a week, hoping to win Irish independence while England was tied down in France. Dunsany reported to British GHQ in Dublin and was sent with a group in a car to relieve an outpost in a Dublin neighborhood. They were ambushed by a Nationalist squad and a ricochet bullet hit him in the face. The Nationalist fighters who took him prisoner apologized and drove him to a hospital. At the end of the week pro-British forces recaptured the hospital. One side of his lip was paralyzed. His recovery was prolonged and he was not ruled fit for service until October, and then only for light duty.

A year later he was posted to France. Shortly after his arrival he wrote to Beatrice from Amiens:

“Imagine Waterloo, Sebastopol, Ladysmith, Pompeii, Troy, Timgad, Tel el Kebir, Sodom and Gomorrah endlessly stretching one into the other; and twisted, bare, ghoulish trees leering downward at graves; and scenes very like Dore’s crucifixion and realities like the blackest dreams of Sime [Sydney Sime, Dunsany’s illustrator]; tanks lying with their noses pointing upwards still sniffing towards an enemy long since stiff or blown away in fragments like wounded rhinoceros’ dying. Imagine the wasted ruin of a famous hill that once dominated all this, now no more than a white mound with a few crosses on it, standing against the sky to show that Golgotha was once more with us.”

In January 1918 he was transferred to the War Office in London, where he wrote propaganda for the home front and the world press, simple stories of soldiers’ lives, incidents from the front. He wrote sharply against the Kaiser but his materials were singularly free of the animosity toward ordinary Germans that was so prevalent at the time. He also wrote two books about the war, Tales of War (1918) and Unhappy Far-Off Things (1919).

The war ended in November 1918. From October 1919 through January 1920 he made a triumphal tour of the United States. Many of his plays were being performed and he lectured in many cities. Two of his plays were running in New York when he was there, and while in New Hampshire he saw a performance of his Fame and the Poet by inmates at the Portsmouth Naval Prison. Yet he had been changed by the war. Mark Amory says of him and Beatrice, “before the war they had been young, now they were not. Dunsany’s greatest friends were dead and he did not replace them.” He lost touch with the Irish Renaissance group. Amory adds, “He believed as a matter of course that the task of an artist was to produce Beauty, but in the 1920s there was little demand for what was small and exquisite.” Though short stories were his metier he turned in the interwar years to novels, publishing nine between 1922 and 1939.

Dunsany and Beatrice, as firm Unionists, were at risk after Sinn Fein declared Ireland independent in 1919 and waged its guerrilla war through 1921. Their gamekeeper at Dunsany Castle, Toomey, was a staunch Republican and helped to divert threatened attacks by his political cothinkers. The Anglo-Irish Treaty established the Irish Free State in the predominately Catholic twenty-six southern counties, breaking off Northern Ireland’s six counties with their Protestant majority to remain part of Britain. The Nationalists split over acceptance of the treaty and a civil war followed with Eamon de Valera leading the anti-Treaty forces in a bitter struggle that lasted until 1923. An anti-Treaty band burned the Kilmessan station near Dunsany Castle and burned a train. Several of their neighbors and the local township were burned out. A car was commandeered from the Dunsany stables to be used as a car bomb, but was found abandoned. The raiders said they “heard his Lordship was a good man and they didn’t wish to disturb him or his family.”

Beatrice wrote in her diary on April 12, 1923, “it is little bits of personal cruelty that throw such a nasty light on the Irish character. When for instance they burnt the stationmaster’s house at Kilmessan (Mrs. Preston and we had to refit them entirely with clothes and furniture last March) they would not let him run upstairs to save his dead wife’s pictures and his money.” In May they returned to England, where Dunsany wrote his second novel, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, which still had eight editions printed between 1969 and 2001.

Chess had always been one of Dunsany’s passions. In the spring of 1928 he played Jose Raul Capablanca, world chess champion, 1921-1927. The showy match pitted the Cuban grandmaster against twenty-one opponents in simultaneous play, three from each of seven countries. Dunsany fought the champion to a draw.

A shooting expedition took Dunsany to India at the end of 1929, lasting into the next year, where he killed more animals, this time from elephant back, accompanied by the Nawab Hamid Ali, ruler of the princely state of Rampur. On his return he plunged into his Jorkens period. Dunsany had invented Jorkens in 1925 with “The Tale of the Abu Laheeb.” Jorkens is the star attraction of the somewhat seedy Billiards Club, a dimly lit male retreat in London. Plied with a few whiskeys, Jorkens entertains the members with accounts of his fabulous adventures. The Abu Laheeb, to begin with, was a legendary sort of Yeti, an intelligent giant sloth living in the reed marshes of the upper Nile in Sudan. Jorkens tells his audience that he had set out to hunt the Abu Laheeb, but after tracking it into the deep reeds saw that it had mastered the art of fire and that made it too close to humans to shoot it. The first of five collections of these stories, The Travel Tales of Mr. Joseph Jorkens, was published in 1931.

Dunsany changed his style several times, from the biblical prose of the Pegana books to the elegiac adventures in mythical cities or on remote English moors, and finally to the realistic locations of Jorkens’ accounts in which improbable events take place. He prided himself on simplicity, and did not consider his work “literary” in any high-flown sense. He prized pure imagination, and so never did research for any of his locales. He loved to make up the names of people and places, an eclectic mixture of sounds pilfered from Latin, Arabic, and Greek. He had a great animosity for modern factories and smoky urban slums. Most of the imaginary cities he created had a vaguely Middle Eastern setting and were made of marble and onyx, with merchant bazaars where emeralds and diamonds were on plentiful display. The Jorkens tales differed in using as settings places he had been on his expeditions.

The Jorkens stories were clever but lacked the esoteric magical feel of his early short story collections or several of his novels. Those remain readily available while the Jorkens books are out of print except for a three-volume hard cover edition edited by S. T. Joshi issued by Night Shade Press in 2005, and even there the first volume can be found only used at exorbitant prices.

Still, Kipling thought highly of the bibulous raconteur. In a 1931 letter to Dunsany he wrote:

“At first I resented the introduction, as camouflage, of your Mister Jorkens. Now I begin to see why your imagination in vacuo (and you’ve got more of it than anyone I know) had to have that peg and the background of the Billiard Club’s atmosphere. . . . For sheer ‘cheek’ the Mermaid yarn [“Mrs. Jorkens,” in which Jorkens marries a mermaid, but she swims out to sea at the end.] is the best. I am not thinking for the minute of anything except the audacity of it.”

World War II found the Dunsanys at Dunstall, just south of London on the flight path of German bombers. They took to sleeping in the cellar and invited the gardener’s family to join them. Dunsany was sixty-one, Beatrice fifty-nine. He joined the Local Defence Volunteers.

The couple had one last great adventure. In September 1940 the British Council asked him to accept a professorship of English Literature in Athens. They were sent to Glasgow, where they took ship, which under wartime conditions kept its route and destination secret from the passengers. It landed them in Sierra Leone on the West African coast, the more direct Mediterranean route considered too unsafe. Then on to Cape Town, where they transferred to a plane that skipped up the east side of the continent, stopping in Mozambique, Kenya, and Sudan, ending in Cairo. While enroute, Greece, which had been neutral, had been attacked by Italy and was now in the war. They crossed the Suez Canal in a rowboat, then went by car and train up the Mediterranean coast to Turkey. They reached Greece at the beginning of January, arriving in Athens eighty-three days after leaving home.

Dunsany lectured two or three times a week, to a standing-room-only crowd when he spoke on Byron. On April 6 Germany declared war on Greece and began bombing the capital. On April 16 the Greek army line broke and refugees began to stream out of Athens. The Dunsanys were offered a no-food place in the hold of a Polish cargo ship leaving for Haifa. They took it. Dunsany slept on the deck while Beatrice and three other women slept on straw mattresses in a small cabin. Water was too scarce for bathing and bread was about the only food available. Dunsany was enjoying himself immensely, writing in a letter, “The lives of refugees are full of interest. One learns what a lot of places there are to sit down, and how to be comfortable, with the help of one’s life-belt. And one learns what good food bread is; water is grand stuff too when you can get it.”

Their ship joined a convoy with a cruiser, two destroyers, and two Greek submarines. Machine guns were mounted on their deck, which fired on a German Stuke. The Stuke bombed a nearby ship but didn’t sink it. They reached Port Said on April 24. Their luggage came on another ship, which was sunk. They went on by ship to South Africa, where they remained the rest of the year, arriving back in Ireland only in March 1942 after a year and a half away.

They spent the next six years at Dunsany Castle. Gasoline was unobtainable so they traveled locally by dog cart. Lacking tea they brewed a drink from garden flowers. The castle did not have electricity until 1946. The lamp oil ration was just enough for cooking, so their cook made tallow candles for light and they used battery lamps for reading. Their son Randal had married a woman named Vera in Brazil just before the war, then served in the British army in India. In 1946 he returned to Brazil, where he first saw his six-year-old son Edward. Randal and his wife brought Edward to Ireland, then broke up the marriage, Randal returning to duty in India, Vera sailing for Brazil, while six-year-old Edward was left permanently with his elderly grandparents. Dunsany was sixty-eight, Beatrice sixty-six. “Little Eddie” did not speak English.

In 1947 Randal remarried, prompting the Dunsanys to deed the castle to him and return to their home at Dunstall in Kent. Little Eddie went with them. In England Dunsany was president of the Author’s Society, he continued writing, and lectured widely. In August 1952 California poet and author Hazel Littlefield Smith visited them, inviting them to come to California. Beatrice had injured her leg, but Dunsany went. Smith wrote an account of their friendship, Lord Dunsany: King of Dreams. He returned to the United States twice more, in 1954 and 1955, including successful lectures during his visits.

Dunsany published a book almost every year: Collections of short stories, The Man Who Ate the Phoenix (1949), and The Little Tales of Smethers and Other Stories (1952); three more novels, one each between 1950 and 1952, and the last of the Jorkens, Jorkens Borrows Another Whiskey, in 1954. Two of his later novels involved men who lived in the bodies of animals. My Talks with Dean Spanley (1936) has the Dean, whose name suggests Spaniel and also Dean Arthur Penrhyn Stanley of Westminster, reminiscence about his previous life as a dog, a far superior animal to a human. This was one of the very few of Dunsany’s books that made it to the screen, in a 2008 production with Sam Neill as Spanley and Peter O’Toole as his attentive audience. Dunsany returned to this idea in 1950 in The Strange Journeys of Colonel Polders, in which the colonel is forced to sequentially inhabit the bodies of many different animals, generally illustrating the evil treatment of animals by humans.

Edward Plunkett died on October 25, 1957, during a visit to Dunsany Castle. Beatrice lived on until 1970.

Many of his stories, including a good number written when he was only in his thirties, are of the devastation, by Time or the gods, of lost causes and doomed cities. “In the Land of Time” has Karnith Zo, the young king of Alatta, literally lead an army against Time’s castle.

“From one of his towers Time eyed them all the while, and in battle order they closed in on the steep hill as Time sat still in his great tower and watched. But as the feet of the foremost touched the edge of the hill Time hurled five years against them, and the years passed over their heads and the army still came on, an army of older men. But the slope seemed steeper to the King and to every man in his army, and they breathed more heavily. And Time summoned up more years, and one by one he hurled them at Karnith Zo and at all his men. And the knees of the army stiffened, and the beards grew and turned grey, and the hours and days and the months went singing over their heads, and their hair turned whiter and whiter, and the conquering hours bore down, and the years rushed on and swept the youth of that army clear away till they came face to face under the walls of the castle of Time with a mass of howling years, and found the top of the slope too steep for aged men.”

A similar story is “Carcassonne.” Actually a city in the south of France, Dunsany chose the name only because one of his correspondents had quoted a phrase, “But he, he never came to Carcassonne.” In Dunsany’s rendition, Camorak the lord of Arn musters his knights to dare to challenge the prophecy of a diviner that he would never come to Carcassonne. Camorak sets out with his troops, fighting their way from fiefdom to fiefdom. Years go by and the knights become fewer and older until only Camorak and one other are left. “Then they drew their swords, and side by side went down into the forest, still seeking for Carcassonne. I think they got not far; for there were deadly marshes in that forest, and gloom that outlasted the nights, and fearful beasts accustomed to its ways.”

Then there are Dunsany’s misanthropic pieces. In his 1933 radio play The Use of Man a group of fox hunters debate which animals are the most useless and could be done without. Lord Gorse swears he will kill all the badgers in the county. Pelby raises the ante, declaring “if a thing’s no good, it doesn’t seem to me that it has any right to exist.” (A thought Bernard Shaw incautiously voiced in his less judicious moments.) Stags are to be allowed because their heads look good on walls. But the hunters can see no use in crows, mice, rabbits, and so on, the most useless of all being the mosquito.

A spirit wakes Pelby, leads him out among the asteroids, and in a gathering of the spirits of the animals asks him, “What is the use of man?” Pelby speaks of building cities, roads, and harbors. The spirits reply, “That is only for man.” He is told that if the animal spirits can find no witnesses in man’s behalf, humans will be eradicated. The dog speaks up, worshipfully, but his testimony is discounted. The crow, bear, and elephant tell how they have been treated by humans (Pelby’s effort to ingratiate the bear by saying he has seen many of them in zoos doesn’t help his cause). And so on through horses, cows, mice, cats, and many more. When the last three minutes is up and sentence is about to be passed one more creature asks for the floor. It is the mosquito.

“THE SPIRIT: What use is Man? Tell this assembly.

“MOSQUITO: I speak for Man. I, the mosquito. Man is my food.” And the sentence is stayed.

In a more pensive vein we have the brief prose poem “Charon,” here condensed to its essentials:

“Charon leaned forward and rowed. All things were one with his weariness. It was not with him a matter of years or of centuries, but of wide floods of time, and an old heaviness and a pain in the arms that had become for him part of the scheme that the gods had made and was of a piece with Eternity. . . . It was strange that the dead nowadays were coming in such numbers. They were coming in thousands where they used to come in fifties. . . . Then one man came alone. And the little shade sat shivering on a lonely bench and the great boat pushed off. . . . Then the boat from the slow, grey river loomed up to the coast of Dis and the little, silent shade still shivering stepped ashore, and Charon turned the boat to go wearily back to the world. Then the little shadow spoke, that had been a man. ‘I am the last,’ he said. No one had ever made Charon smile before, no one before had ever made him weep.”

Lord Dunsany’s legacy is undeservedly obscured. S. T. Joshi, in his preface to Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination, suggests the reasons:

“Dunsany lives, if at all, as a respected but ill-understood figure in the modern fantasy movement, an acknowledged influence on such later figures as H. P. Lovecraft, J.R.R. Tolkien, Ursula K. Le Guin, and others.” Joshi attributes this neglect to the ghettoization of fantasy and other genre fiction in reaction to “the dominance of cheap pulp magazines,” especially in America. “As a result, there developed a rather ignorant and small-minded unwillingness on the part of mainstream critics to consider any material of this type as falling within the realm of genuine literature. . . . Dunsany naturally suffered from this prejudice, even though he had never appeared in the pulp magazines.”

Dunsany is most of all an antidote to the addiction to politics, to over-absorption in questions of rulership and policy. A reminder that advocacy of protecting nature is not the same as experiencing the natural world. There is a beautiful little vignette, “The Day of the Poll,” in his A Dreamer’s Tales in which a poet persuades a dedicated voter to accompany him on election day to the top of a hill outside of town overlooking the sea.

“And for long the voter talked of those imperial traditions that our forefathers had made for us and which he should uphold with his vote, or else it was of a people oppressed by a feudal system that was out of date and effete, and that should be ended or mended. But the poet pointed out to him small, distant, wandering ships on the sunlit strip of sea, and the birds far down below them, and the houses below the birds, with the little columns of smoke that could not find the downs.”

Happily for us some possibilities remain. Skarl continues his drumming and Mana-Yood-Sushai sleeps on, at least for a while.