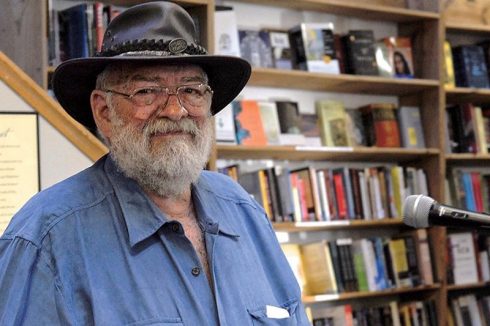

The Last Bohemian: Lionel Rolfe

Former Herald Examiner columnist and longtime literary Los Angeles chronicler Lionel Rolfe died in his sleep of a heart attack on November 6thin Glendale at the age of 76. Beginning his freelance journalism career at 16, Rolfe wrote 9 books and lived almost all his life in California. His best-known book, Literary L.A, first published in 1981 by Chronicle Books, is a pioneering work covering a century of Los Angeles literature. Rolfe’s tireless work on the history of LA writers foreshadowed the explosion of studies on Los Angeles literature years ahead of the curve.

Rolfe became immersed in the Los Angeles cultural community while at Los Angeles City College in the 1960s. A devoted denizen of long-gone 1960s coffeehouses like Pogo’s Swamp, Rolfe wrote columns for the Los Angeles Free Press and was later blacklisted for his work with the Communist Party.

Social historian Mike Davis knew Rolfe almost 55 years. They met at Dorothy Healey’s (head of the Communist Party in LA during the Fifties and early Sixties) when they were both in their early 20s. Davis told me recently via email, “I’ve always thought of Lionel as LA’s last true Bohemian. He had a Rabelaisian appetite for local history, music, poetry and good company. His life mirrored his passions and I’m not sure that anyone will ever ‘know’ LA in the full sense that he did.”

As Davis notes, Rolfe knew the literary underground better than just about anyone. In the chapter, “Hidden Links” in the 2002 edition of Literary LA, Rolfe explains a guiding spirit to the book and his work cataloging Los Angeles authors when he writes: “This book tells the story of what they as California iconoclasts gave to the nation and world in terms of the written word, not as an exhaustive history, but rather as a personal record by one who readily acknowledges how deep bohemia’s influence was on him.”

Rolfe worked as a journalist almost 60 years writing and freelancing for publications like the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco Chronicle, Pasadena Weekly, Huffington Post, Pismo Beach Times, Newhall Signal, Los Angeles Herald Examiner, Los Angeles Free Press, the Jewish Press, as a police beat reporter both in Oakland and the LAPD and countless other writing jobs. His 1998 essay collection, Fat Man On The Left, Four Decades in the Underground, is a compendium of his darkest hours in the trenches.

Born in Medford, Oregon in 1942 where his father Benjamin Rolfe was stationed in World War II, his mother Yaltah Menuhin was one of three Menuhin child prodigies who became world famous musicians. She became a well-known pianist, artist and poet. His uncle, Yehudi Menuhin, was a violinist and conductor and considered one of the greatest violinists of the 20thCentury. The Menuhins were very vocal in their disgust with racism and intolerance and their fighting spirit influenced Rolfe from a very early age.

Though Rolfe mostly lived in Los Angeles, he also lived in the Bay Area early on. “I grew up in San Francisco as a kid on Steiner Street. We moved to L.A. when I was about 10,” Rolfe told me in 2011. For a few years they lived in the Belmont Heights district of Long Beach. “It’s where I learned about anti-semitism at Woodrow Wilson High School,” he says. “The son of a local Christian minister led a group of pals and beat me up in the alley on the way home, calling me a Christ killer. The town was still Midwestern.”

“I used to deliver the Press Telegram and I tried to form a union of us delivery boys. As part of a program to buy me off, they took me down to the city room and showed me stuff and I got newspaper fever after that.” Rolfe had always loved books and started writing his own articles in high school when they moved from Long Beach to Hollywood. After Wilson he went to Los Angeles High School for a year and finally he fell by Fairfax where he graduated.

“Dorothy Healey was my hero. When I was 16, I would go to her house near 84th Street,” Rolfe told me. “I would ask her a political question and she always had some fascinating way of describing what was really going on.”

When Rolfe first attended LA City College, he “tried filmmaking but ended up writing.” He briefly shared an apartment with Ron Karenga, later the head of Black Panther adversaries: the US Organization. “I did like City College,” he says. “Went to the Xanadu, the coffeehouse where blacks and whites first got together, fought civil rights wars. Heard a lot of jazz and rhythm and blues. It was exciting.”

LA City College was an epicenter for activists and artists during this era. Rolfe then transferred to Cal State LA, but ended up dropping out a semester before graduating. He never did get a degree but this did not stop him from being a full-time journalist by 23.

Rolfe’s first journalism job was writing for the Pismo Beach Times. “I loved the way the fog came in,” he said “and made the place so magical and beautiful. It had a real Steinbeckian quality to it.” Relocating to California’s Central Coast for awhile as a young journalist gave Rolfe an opportunity to do a lot of writing and the space to do it. “We changed the front page for three different editions of the same paper. There also was the Arroyo Grande Herald-Recorderand the Grover City Press.” Rolfe got used to producing constant new articles, a skill that served him his whole life.

Rolfe always said that he really found his voice writing for the Los Angeles Free Pressalso known as “The Freep.” The Los Angeles Free Press, Rolfe told me, “was the first underground paper. Then a string of them developed all over the country, inspired by the Free Press. They helped to fight the war in Vietnam. After that a new kind of paper, based on the underground paper developed. In Los Angeles the last editor of the Free Press became the first editor of the Los Angeles Weekly, which was the first ‘alternative paper.’ The Reader, which I mostly wrote for, started about the same time. The alternatives grew up in the late ’70s, when the underground papers were imploding.”

Throughout the 1970s, Rolfe stayed on the forefront writing all day, everyday and for whoever would pay. Along the way he met a few editors that gave him a break. One of them was Scott Newhall. “Scott Newhall,” Rolfe said, “was the editor of the San Francisco Chronicle which was the first major American daily to 1) oppose McCarthyism and 2) the war in Vietnam,” Rolfe says. “Scott also owned the Newhall Signal. He was on the board of the Newhall Land and Farming Company. He hired me to work at the Signal especially when he found out I had been blacklisted by the California Newspaper Publishing Association because of my ‘Communist’ youth. He was the last of the great pioneer editors. Under him, the Chronicle emerged as the strongest newspaper in San Francisco.” Newhall liked Rolfe so much that he began publishing Rolfe’s articles in both the Newhall Signal and the Chronicle. This would later lead to Chronicle Books publishing one of Rolfe’s books.

“By the ’80s I was freelancing a lot for LA Times and then the Herald Examiner,” Rolfe said. “Most of Literary LA was written in this period as magazine pieces. I wrote about writers who I felt were the great writers to come out of LA., or at least very noteworthy. My first piece was about Thomas Mann and the controversy over Schoenberg.”

These columns cataloged the bohemian and apocalyptic streams within Los Angeles writing. Week after week, in his Sunday Herald Examiner column, he wrote profiles of writers like Henry Miller, Robinson Jeffers, Malcolm Lowry, Charles Fletcher Lummis, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Oscar Zeta Acosta and many others. “I tried to include everyone I thought had been missed by ‘history.’”

In 1981 Chronicle Books compiled his Examiner columns on Los Angeles writers and called the book Literary LA. Weaving together a century of LA writers, the book was a unique title during the Reagan era. The UCLA librarian and celebrated author, Laurence Clark Powell had chronicled literary LA during the 1960s and early 1970s as had Carey McWilliams in the 1940s and 50s, but there was not much in the way of really writing about Los Angeles authors for many years. Rolfe’s Literary LA was a groundbreaking book that paved the way for later studies of literary Los Angeles like Mike Davis’s chapter, “Sunshine and Noir,” in the 1990 title, City of Quartz.

Over the years, Rolfe’s original book has been expanded and republished three times. In the 2002 edition, published by California Classics, Rolfe wrote in the final chapter “In Search of Literary LA,” that “Time and place have been called disappearing characteristics of modern fiction in America for decades now, but in Los Angeles time and place are still the stars of our drama. Perhaps time and place are ephemeral phenomena, in life and to a lesser degree in literature – maybe both are a writer’s conceit, construct or facile artifices. But the fact is that Los Angeles has put its garish mark on world literature with them. Desert sun and fire, the multivariate moods of nature and light, and artificial spotlights and glows have given the place its own special luminescence.”

I bought a copy of Literary LA around 1994 at Chatterton’s in Los Feliz right before it was renamed Skylight Books. I was an undergraduate at UCLA at the time and Rolfe’s informative prose became a big inspiration. In 2010, I finally met Rolfe, interviewed him shortly after and got the chance to have many more conversations with the author over the last eight years.

Rolfe liked to say that his journalistic style was reminiscent of Mark Twain. He liked to go all over the place, but remain connected to a central idea. His articles on authors inter-mingled personal experiences with the writers and inside anecdotes supplemented by his encyclopedic knowledge of Los Angeles history and geography. His candid stories about seeing Bukowski at the Xanadu Coffeehouse or hanging at the now long-gone Papa Bach’s bookshop with poet proprietor John Harris, captured the zeitgeist of those times.

In December of 2014, a special tribute event was held in Santa Monica to commemorate Rolfe’s contribution to literary Los Angeles. Rolfe was interviewed on stage by Tom Lutz, chair of the Creative Writing Department at UC Riverside and editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. I was in the audience that day and in addition to their long free-wheeling conversation, Lutz earnestly thanked Rolfe for all he had done chronicling Los Angeles literature over the last five decades. Around this same time, Rolfe had donated a half-century of his writing and research to be archived by the Special Collections Library at USC’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Collection.

In 2015, Rolfe had a stroke followed by a long illness and was later placed in the Glendale Healthcare Center where he spent most of the last year of his life. Rolfe was married three times, each one ending in divorce. He is survived by his daughters Hyla Douglas and Heather Pearce, by his grandchildren Caspin Hargreaves and Kara Pearce and his brother Robert Rolfe of Virginia in addition to an extended family of numerous good friends, fellow writers, artists and musicians.

A memorial will be held on Sunday, November 25th. For details on the service, email his daughter Hyla Douglas at hyladouglas@yahoo.com. Thank you for your life’s work Lionel Rolfe. In the current era of corporate coffee and gentrification, you managed stay true to your original values until to the end. Goodbye Lionel, you really were LA’s last true bohemian.

First published in the Cultural Weekly, November 21, 2018

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.