The Grand Old Man of L.A. Letters

[This essay on antiquarian bookdealer and scholar Jacob Zeitlin (1902-1987) is from the second edition of Lionel Rolfe’s Literary L.A. (California Classics, 2002).]

Lionel Rolfe

THE GRAND OLD man of Los Angeles letters, Jake Zeitlin, invited me to lunch after reading my original Literary LA. When I showed the invitation to my librarian friend John Ahouse, he commented I might want to hang on to it because a handwritten letter from Jake Zeitlin was a treasure in itself. I figured if a letter from the man was worth something, a lunch with him could be worth even more.

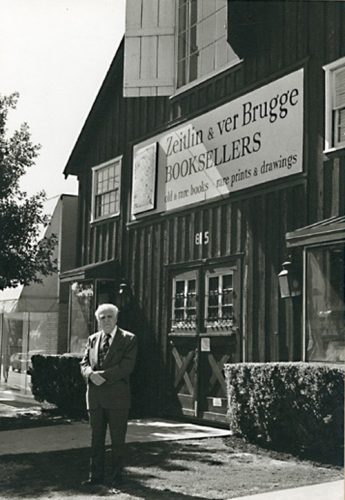

Jake has been gone from this earth for a while now, but when he was alive, I often found myself driving past the striking red replica of a Pennsylvania Dutch barn on La Cienega, just below Santa Monica Boulevard. But until I went inside to meet Zeitlin, I had never been through the door of Zeitlin & Ver Brugge, dealers in rare books, manuscripts and letters. The stuff of history was stored in book shelves that climbed up to the second-story rafters of the building. It was also there in the lives of the man and woman who owned the barn. Josephine Zeitlin, whose maiden name was Ver Brugge, presided over the business office. Zeitlin, a stocky, handsome man even into his eighties, was the bookman incarnate.

After concluding business over the phone, he got up and we left, driving in Zeitlin’s car to a Beverly Hills cafe nearby. During lunch we talked about many writers he had known, including Robinson Jeffers, Aldous Huxley, Thomas Mann and Henry Miller. Huxley was the chief topic of conversation, however, because through my family connections, I had met the man and also got to know his widow, Laura Archera Huxley. Zeitlin, through his association with the agent William Morris Jr., had introduced Huxley to Hollywood, hence to the City of the Angels, where the great British author spent the last two decades of his life. As an important figure in Los Angeles literary history, Zeitlin had strong opinions about various people, but did not necessarily want me to broadcast them.

I guess he might have been referring to the fact that he didn’t much like Henry Miller, and he appeared rather dubious about Robinson Jeffers’s wife.

But Zeitlin was also willing to share gossip without embargo as well. Opening his briefcase, he showed me letters from Frieda Lawrence, widow of D.H. Lawrence, whose estate—namely all the late author’s manuscripts—Zeitlin once represented. One of the letters he showed me cleared up a mystery that had always puzzled biographers of the great poet Robinson Jeffers—namely, what happened when Robinson and Una Jeffers went to visit Frieda Lawrence in New Mexico, leaving their Carmel home behind. The Jefferses were noted for never leaving the stone castle he had built on the rocks by the sea. Yet somehow Frieda Lawrence persuaded them to leave “Tor House” and come to live with her for a while. Lawrence, it should be remembered, had had a flamboyant and notorious love life, and the widow also was believed to have had hopes that Jeffers would stay and become the poet of the Southwest. What did happen instead was that Jeffers went into another room to talk with a Swedish woman friend of Frieda’s, a woman with a dubious reputation. Convinced that Robinson had already fallen for the woman’s charms, Una shot herself, crying out that since her husband needed her no more, she was going to end it all. Over the next several weeks, Frieda nursed Una back to health. I read all this in a letter—with amazement.

For our next meeting with Jake, Nigey and I went over to the Zeitlin’s house for dinner. Jake, you must know, was always much more than one of the world’s great dealers in rare books and letters. He was a catalyst of Los Angeles’s cultural community, much of it bohemian, going back to the twenties. Zeitlin had a providential meeting when he first came to L.A. with Charles Lummis—Lummis had been the original bohemian catalyst in L.A. and Jake eventually took his place.

Lummis sought Zeitlin out at the downtown Bullock’s where he worked in the book department. Zeitlin had a reputation as a promising bohemian poet, and Lummis always made it a point of meeting those young writers he thought were on the way up.

Zeitlin had arrived in Los Angeles in 1925, hitchhiking across the Southwest—hitchhiking and hoboing. Zeitlin grew up in Fort Worth. He developed the habit of leaving his family home—either early in the morning or late at night. He would just take off, “just disappear, sometimes for a week, sometimes for many weeks.” He would get jobs during harvest season, and in the process he had collected many folk songs, which is why poet Carl Sandburg had come calling on him in 1922 in Texas and later paid Zeitlin lengthy visits when the “young poet” lived in his redwood home in Echo Park. Zeitlin’s extensive knowledge of folk songs was also the reason Leadbelly, Alan Lomax and others came to pay their respects.

He learned the excitement of being a bookseller early on. Zeitlin used to drive a truck for his family’s business, and one of his helpers was a fellow who had once worked at Saints & Sinners Corner, the rare book room at A.G. McClurg’s Bookstore in Chicago. This peripatetic litterateur was a nonstop talker, and his talks had their effect on the 18-year-old Zeitlin, who decided that “the most wonderful thing in the world would be to have a book shop where people could come and browse and talk.”

Zeitlin also decided that he did not want to stay in Texas with the family business—a family business that survived Zeitlin. His family had moved to Texas in 1905 when he was three years old, from Wisconsin, where he was born. The family first tried farming, “but what the boll weevil didn’t get, the Johnson grass did. We were not farmers.” Next the Zeitlins became fruit peddlers in “the way a lot of Jewish immigrants did. They dealt with the things that the people who had made it didn’t want to bother with.” In this particular Russian Jewish family’s case, these things were vinegar, condiments and similar foodstuffs.

As a young man in Texas, Jake had quickly gained a reputation as a poet and literary critic—an early newspaper article claimed that Zeitlin looked like the legendary bohemian, poet and character George Sterling, which Zeitlin today insists was a totally preposterous notion except, perhaps, for the nose— “We both had the same kind of nose.”

Zeitlin ultimately headed for L.A., telling himself that he was coming to the big city to develop as a poet. The truth may have been something else. Zeitlin says that he didn’t have the first prerequisite of a writer—an ability and talent to sit down and not get up. Sitzfleisch, says Zeitlin, was described by H.L. Mencken as the “ability to put one’s rear onto a seat for a long period of time.”

A bookseller, Zeitlin says, “can expend a lot of energy in a lot of different directions and get a percentage of good results.” And that’s the kind of mentality he says he has—one that goes off in a number of different directions at once. Although Zeitlin once said he decided to go West instead of East by the flip of a coin back in his native Texas, he says that ultimately L.A. appealed to him because he was just a good “country boy” at heart; he never really liked big cities.

It was a happy meshing of person and place. In 1925 Los Angeles was still a big enough city to impress a country boy—he had never seen so many people at the same time in one place. After a couple of false starts, Zeitlin located in Echo Park and stayed there from 1926 to 1938. During that time Echo Park was the locus of a flourishing bohemian scene, and Zeitlin’s various bookstores in downtown Los Angeles became a part of it. Zeitlin said the bohemian scene in Echo Park even had a novel—a rather peculiar novel—written about it.

It was called The Flutter of an Eyelid, by Myron Brinig, published in 1933. One of the novel’s main characters is obviously meant to be a representation of Jake, except that if you know the man you know that the characterization was simply not accurate.

Sol Mosier in Brinig’s novel is a decadent Jew, a composite of every anti-Semite’s catalog of cheap, hackneyed prejudice. Yet another of the characters was clearly based on Aimee Semple McPherson, the famed evangelist who built her Angelus Temple next to Echo Park Lake in the twenties.

The book was written to shock, but in contemporary terms it reads like a pretentious effort to describe a group of outlandish bohemians set in a garish, surrealistic Southern California setting that is destroyed in the Great Earthquake.

Pick whichever Great Earthquake you want. A fairly serious although not catastrophic earthquake hit Los Angeles and Long Beach in particular in the early part of the thirties, about the time Brinig—who was Jewish himself, by the way— was writing his book.

Among other things, Brinig’s Zeitlin character decides to take a vacation from his sybaritic existence and goes on the road in order to show that he can be a drifter and a day laborer, just like a goy. After a couple of misadventures, Brinig’s character decides that Jews apparently are not cut out for hard living and physical work and, giving up the attempt returns to debauchery and drugs. Zeitlin says he had befriended Brinig because he seemed such a lonely soul— “a sulky baby elephant,” who had “a certain way of winning your confidence.”

Zeitlin did not particularly like Brinig, even in the beginning. But he was very struck by another writer, Carey McWilliams. McWilliams became not only an important California author but also, for many years, was editor of The Nation, one of the country’s oldest and most influential political magazines. Factories in the Field and Southern California: Island on the Land were among McWilliams’ classics—the latter volume was the foundation which every book on the subject since then has built upon. I was surprised to learn from Zeitlin, although I shouldn’t have been, that McWilliams rarely made money from his books. He always paid the bills with his job as magazine editor.

McWilliams was one of the star writers of Opinion, published briefly from October 1929 to May 1930, out of Zeitlin’s bookstore at 705 ½ W. Sixth Street. They remained close friends until McWilliams’ death in 1980. Zeitlin believed that the period and the people around Opinion represented a Los Angeles renaissance.

After the nice dinner cooked by Jake’s daughter Adriana, we all sat down to talk further into the night. I had read McWilliams’ 1927 article in Saturday Night magazine that told how Zeitlin, a young poet from Texas and “protege of Carl Sandburg” had just arrived in Los Angeles.

Zeitlin immediately pooh-poohed his own poetry, saying that over the years he may have “flimflammed” some people into believing he was a poet, but Sandburg was not really one of them. According to Jake, Sandburg wrote the introduction to a slim volume of Zeitlin’s poetry not so much out of enthusiasm for the poetry, but because Sandburg “liked me.”

In McWilliams’s account of Zeitlin’s life on the Echo Park Avenue hilltop there’s a wonderful description of Jake “gazing down at night into a pool of liquid darkness, with flares of light in its shadows, while night odors and sounds drifted up the hill.” The McWilliams article also includes some of Zeitlin’s poetry despite his modesty, while it may not have been the stuff of genius, it was not at all bad and in fact was quite vivid and intelligent.

As we talked, Zeitlin seemed to get caught up in the memory of it all. Asked why bohemianism flourished in Echo Park, Zeitlin says the answer was simple. The rents were low, the shacks on the tree-filled hills afforded more privacy than flatland apartments did, and people could conduct their individual lives in peace.

“Bohemianism thrives on adversity. It’s not a movement but a consequence of certain conditions. You have to have a concentration of people practicing their arts, people with superior endowments who don’t necessarily fit into society, and who are, in fact, often engaged in rebellions against convention, creating a symbiotic society where not only can they go and eat at each other’s houses when they’re hungry, but where they can also spark each other and be each other’s critical audiences. To such people, money is not the main motivation; they may like spaghetti and wine and women and conversation and not getting up in the morning to go to a job, but all believe in practicing something that is their justification for being, whether it be dancing, writing, sculpting or music.”

Zeitlin then relates what is obviously one of his sweetest memories from long ago. “Someone had tied a long rope with a tire to one of the trees at the end of Echo Park Avenue, so you could stand on one side of the little canyon there, grab hold, and swing out over it, describing a sort of semicircle. If you were lucky, you’d land back on the hill. One night when Sandburg came visiting and the moon was bright, and we had imbibed a considerable amount of good wine, we went walking up toward the trees. I reached out and grabbed hold of the tire and swung out. I had no idea he was going to do the same thing—as soon as I got back, Sandburg gave a Viking war whoop, grabbed the tire, swung out over the canyon, and managed to get back to the other side without falling off.”

On another drunken, full-mooned night, Zeitlin remembers walking along a ridge and seeing a naked woman coming at him. He called out to her, but she dove off the side of the road into the bushes. He called her again, but she had disappeared. He continued walking toward the house from which the naked woman had apparently come. Zeitlin recalls that one of the revelers at that party was director John Huston. Huston ran with a circle that included “a rather peculiar man who fancied himself a reincarnation of Edgar Allen. His name was Ben Berlin—an abstractionist of considerable originality.” Berlin was part of a group called the Art Students League, an organization whose headquarters downtown on Spring Street, said Jake, “always smelled of rancid cabbage being cooked.”

Jake says a number of important artists came from the glens of Echo Park —John Cage, the avant-garde composer; photographer Edward Weston (in fact it was at Zeitlin’s bookstore where Edward Weston had his first show in 1928). Others who didn’t necessarily hang out in Echo Park but were connected there because Zeitlin’s shop hosted early shows of their work included Rockwell Kent with his magnificent woodcuts; and artists Paul Landacre, Peter Krasnow and Millard Sheets.

He talks more about the group who followed Ben Berlin, who lived for a while in a house that belonged to Miriam Lerner, a woman who was active in the Young People’s Socialist League at the same time she was private secretary to Edward J. Doheny, the oil company mogul, whose name was immortalized in the Teapot Dome scandal. Lerner had gotten the young Zeitlin jobs mowing lawns in Doheny’s gas stations all over Southern California; sometimes he even mowed the lawn at the Doheny estate—where years later as a bookseller he would be invited for tea.

Miriam Lerner was immortalized as “M” in Edward Weston’s Day Books. She posed for a lot of Weston’s pictures as well, and had a torrid affair with the photographer. Later on, Lerner became secretary to writer Frank Harris.

Echo Park in the twenties was a place that reverberated with bohemia. One of Jake’s most treasured mementos of the time and place was a photograph of Carl Sandburg at the Edendale Red Car stop down the hill from the Echo Park neighborhood, taken either by Weston himself, or his partner, Margarethe Mather. Original prints of that photo now go for five thousand dollars and more.

But the most memorable of Jake’s Echo Park experiences was hanging out with Sadakichi Hartmann, who had been the very archetype of bohemianism in the early days of Greenwich Village. But by the time Zeitlin met Hartmann, at a dinner at a friend’s house on Temple Street, Hartmann was no longer writing or being published.

“It was Sadakichi,” Zeitlin says with a slightly wicked laugh, “who brought the disease across country.” Hartmann came to Los Angeles, like so many others in those days, because he had asthma and his doctor had advised him to go west. Once proclaimed “The Most Mysterious Personality in America,” Hartmann was physically a giant of a man, “a fascinatingly ugly man, half-German and half-Japanese, who among other things had written the first good book on Japanese prints.” Hartmann had also known and interviewed the painter Whistler, the wit and playwright Oscar Wilde, and poet Walt Whitman.

The son of a German consul stationed in Japan and a Japanese mother, Hartmann was educated in a German military school, against which he rebelled. Zeitlin says the result was a funny combination—he was very Germanic, but then “he would suddenly break out and go absolutely wild.”

When Zeitlin first met Hartmann, the latter had been reduced to earning a living not by writing but by playing a sort of buffoon-bohemian role for the amusement of others. He did a “strange, grotesque sword dance that scared the hell out of you,” Zeitlin says, chuckling at the recollection. “He always celebrated his birthday at least four times a year, and always it was a benefit for Sadakichi Hartmann.” Hartmann became even more of a professional bohemian in his last years, says Zeitlin, when he was discovered by such Hollywood celebrities as Douglas Fairbanks, W.C. Fields, Gene Fowler and John Barrymore, who used to hire him to be a mascot and buffoon at their get-togethers. Along the way, Hartmann played the role of a magician in a Fairbanks version of “Sinbad the Sailor.”

By the end, says Zeitlin, Hartmann had become a miserable character; alcohol was getting hold of him, and he did not always present a very pretty picture. That Zeitlin was intrigued on the occasion of their first meeting is no wonder. Sadakichi had approached the young Zeitlin at the dinner put on by the Temple Street host, but not before grabbing a loaf of bread and a bottle of wine from the host’s table. He turned to Jake and said, “I want you to meet my good friend Aline Barnsdall.” She, of course, lived in that magnificent place known today as Hollyhock House in Barnsdall Park east of Hollywood, a place not actually designed by Frank Lloyd Wright but by his son Lloyd Wright, Zeitlin insists. Other Wright disciples like Robert Schindler and Richard Neutra also worked on the house, Jake adds.

So, there were Hartmann and Zeitlin marching down Sunset Boulevard toward Barnsdall’s house at one in the morning. The closer they got to the house the more Zeitlin protested that the time was wrong for such an impromptu visit. But no, Hartmann insisted, Aline Barnsdall was a good friend and surely she would welcome them. As they got up the hill to the front door, however, a guard burst forth and blinded them with a flashlight, demanding to know what they wanted. When Hartmann ordered the guard to wake up his “good friend,” the guard replied that he would do no such thing; further, he added, if the two men weren’t off the property in five minutes, he’d call the police.

Zeitlin chortles at the memory of the two of them running down Sunset Boulevard afterward. “Imagine little me running alongside this giant, gawky Ichabod Crane figure. If the cops had seen him, they would have turned and run after them. But for all that, Hartmann was someone to be taken seriously. He knew a lot about art. He had been the very symbol of bohemianism—and he infected the L.A. atmosphere with this terrible bohemian disease.”

Zeitlin did not stay a bohemian poet for long. For one thing, he had a young wife and child. So, he held a series of odd jobs, of which the truck driving and lawn mowing jobs Miriam Lerner had obtained for him were just a couple. But then the inevitable happened—in his first year in Los Angeles he got a taste of the book business. He went to work at the Holmes Book Company, and although he was fired in a few weeks for “incompetence,” he was set on his life’s work. He came home with no job and took what little money the couple had, paid a month’s rent in advance, laid in some groceries, and lo and behold, within a few hours their home was struck by fire. Enough of the kitchen was left to cook a meal by candlelight; but to sleep he and his first wife Edith had to find other quarters right away.

It was at that dinner in the burned-out house that the future was decided. Jake and Edith and a friend who had come out from Texas to try his luck in Los Angeles sat down to their meal. The friend chewed meditatively for a while and then remarked as how he thought they had all given L.A. their best shot—now was the time to call it quits and go home. It was at this point that Zeitlin made what has been known ever since as “The Speech.” He announced that he would never go home to Texas; rather, someday he would have his own bookstore, with the finest rugs hanging from the balconies, etchings by the likes of Rembrandt and Durer everywhere, and the best stock of rare books in all of Southern California.

Zeitlin had already begun dealing in books—but he wasn’t making what anyone might call a living from it. It wasn’t until 1928 that he got his first bookstore, a twelve by fifteen-foot hole-in-the-wall next door to the public library. Lloyd Wright had told Zeitlin that he couldn’t keep selling books out of a satchel. He needed a shop where people could come to him. So, Wright and Carey McWilliams helped him find, decorate and organize the first of his downtown bookstores. A year later he moved around the corner from Hill to Sixth Street; toward the end of the Depression in 1938, Zeitlin trekked west with the rest of the town—to Westlake Park. A decade later, after his marriage to Josephine he made his final move to the red barn on La Cienega Boulevard.

*

Over the years Zeitlin earned a reputation as one of the world’s top dealers in rare books and science manuscripts. Though Zeitlin had first announced himself on the Los Angeles scene as a poet, science is what he really loved. He had tried upon his arrival in Los Angeles to get a job at a museum; in Texas he had been a respectable local amateur birdwatcher who had even had publishing credits in the field.

These specializations did not obscure his continuing involvement in literature, however. Early in Zeitlin’s career, a man wandered into his bookstore who would have a large impact on the city’s intellectual life as well as Zeitlin’s career. He was Elmer Belt, a physician who may have been one of the consummate book collectors of all time. Belt eventually would assemble the greatest collection of books relating to Leonardo da Vinci outside Italy, a collection that eventually went to UCLA. He was also the personal physician of evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, as well as of the “American Zola,” Upton Sinclair, whose books he collected with a fervor almost equal to that which he devoted to his hero da Vinci; the Sinclair collection is now housed at Occidental College. Among many other things, Belt was a prime mover in the founding of the UCLA Medical School.

Zeitlin told of his arrangement as Belt’s primary da Vinci supplier in a eulogy he delivered at UCLA for Belt, who died at the age of 87 in 1980. During the Depression, the doctor’s office was across the street from Zeitlin’s bookstore, and the deal he made with Zeitlin helped immeasurably toward keeping the latter in business. Belt said he could afford to spend $200 a month on da Vinci, which Zeitlin admits was an important part of his cash flow in those days. But in return, Belt told Zeitlin to go easy, not to overcharge him.

“If you do, I won’t buy anything else from you,” he said. The relationship between Zeitlin and Belt proved to be lifelong and close.

*

When all is said and done, Zeitlin’s greatest impact on Los Angeles was through the books, resources and people he directed to UCLA.

Starting in 1927, Zeitlin supplied many of the basic books that the university’s new library needed; it was largely through Zeitlin’s efforts that UCLA obtained Belt’s da Vinci collection years later, and it was Zeitlin who “discovered” the man who would become UCLA’s great librarian, Lawrence Clark Powell. During the thirties and forties when Powell was head librarian, he intentionally set out with Jake’s help to equal the Bancroft Library’s collections on the Berkeley campus.

Powell came into the bookstore a little late in the game, catching only the tail end of the original scene that emanated from Zeitlin’s downtown operation. Powell was not part of the inner circle that published Opinion in 1929 and 1930, for instance. But of greater significance than Opinion was the emergence of the Primavera Press in 1928 from Zeitlin’s shop. Through this publishing company Zeitlin became the first patron of three great printers Los Angeles has produced: Saul Marks, Grant Dahlstrom, and Ward Ritchie.

Powell first visited Zeitlin’s bookstore in 1928. It was, he said, “a crack in the wall with a grasshopper sign on the window. There was no other shop in town like this tiny oasis where time relaxed its grip, an incarnate answer to Cobden-Sanderson’s prayer, ‘sweet God, souse me in literature!’—a place fragrant with oil of cedar, where purchases were wrapped in orange and black patterned paper.”

Powell lived in Paris during the first three years of the thirties. While he was there, Primavera Press commissioned him to write a biography of the poet Robinson Jeffers, who had grown to manhood in Los Angeles. When Powell returned to Los Angeles in 1933, his first volume was published. He went to work at the bookstore and moved into a house near Zeitlin’s in Echo Park. The Jeffers biography sold out its first printing of 750 copies despite the fact it had appeared well into the Depression. Its popularity owed a lot to the fact that it was illustrated by Rockwell Kent, but it was a good and interesting book about a then new and important figure.

Three years later, however, the Depression was really in full sway, and Primavera folded. Its traditions, however, were carried on for years after that by the late Ward Ritchie, whom John Ahouse took me to meet in 1994.

Ritchie began in the thirties as the printer for Primavera, operated a successful commercial press for many years on Hyperion Avenue, and was living in very active retirement in Laguna Beach. He had a lovely Spanish-style house, and actress Gloria Stuart who later appeared in the movie “Titanic” was his longtime companion.

Ritchie was of the strong opinion that today’s books are overly dominated by graphics. “It’s not the type that’s conveying the message anymore,” he said. What was ironic about this comment was that Ritchie’s own style was heavily influenced by François-Louis Schmied in Paris, with whom he had apprenticed in the thirties, and whose books with their eye-catching graphics are still highly sought after today. Ritchie had an enormous 1835 English hand-press in his basement on which he still published limited editions under the imprint “Laguna Verde Imprenta.” On his work desk were some current designs for the Historical Society of California. Ritchie was still very busy, not only producing books by hand but also designing books for the University of California Press. He designed about 75 titles for them. He also had printed about 25 volumes by Robinson Jeffers over the years.

*

Perhaps it really is hard to say where Zeitlin’s influence on the intellectual life of Los Angeles was felt the most, for he seems to have brought together so many people for so many different reasons for so many years. It would be remiss of me if I did not mention I had an interesting business transaction with Jake. I didn’t meet him because of the business dealings—rather the dealings evolved out of my meeting him.

My mother had grown up knowing Willa Cather, “Aunt Willa,” who was also her Shakespeare teacher. She came to love Willa more than she did her own mother, who in later years she even came to despise. My mom had exchanged many letters with Willa over the years and I had heard her read many of them aloud. I was especially interested, because some of them mentioned what a cute baby I was.

Scholars and writers had been trying to see those letters for years, but while Willa was alive and while Edith Lewis, her executor and long-time companion, was active, my mom would let no one read them.

In the eighties I was going through a particularly rough time as a freelance writer, so my mother just packed the letters into a regular airmail envelope and sent them to me for Jake to sell. He sold them to the Cowboy Museum in Norman, Oklahoma. I paid some back rent and even took a short vacation to San Francisco. Jake was more generous with me than he really needed to be, advancing me funds against the expected sale, which kept me going. Eventually the letters went to Princeton University.

Zeitlin’s relationship with Huxley was of greater moment than my encounter with him. Huxley wrote a lot about the town and place, and his ideas particularly influenced the younger generation coming up during the sixties in Los Angeles. Zeitlin first met Huxley in the spring of 1938 at Frieda Lawrence’s ranch, where he began the job of cataloging and offering for sale the manuscripts of her late husband. Zeitlin met Aldous and Maria and was close to both until their deaths. They became friends during several days spent in the beautiful New Mexico landscape, which included not only many long conversations, but also the viewing of Indian rain dances. “And it rained—it rained torrents,” Zeitlin recalled. He was particularly proud of the inscription Huxley once wrote to him: “For Jake Zeitlin, our guide, philosopher and friend in the West.”

Zeitlin convinced Huxley to come and work in the Hollywood movie studios, which paid well. Moreover, Zeitlin helped Huxley burn his first drafts of a screenplay, so bad was it. There was Huxley, pulling down $2,500 a week—in the late thirties yet—but judging from his first effort, it appeared that he might never be a screenwriter. Nevertheless, Huxley went on to eventually write some good scenarios. His script for “Pride and Prejudice” is considered a Hollywood classic.

Zeitlin also brought in his friend Powell, who was hungry and out of work, to do the job of cataloging the Lawrence manuscripts. In the process, Powell also became close to Frieda Lawrence and the Huxleys—friendships which would be important to the UCLA collections Powell would one day develop. You can understand why Powell would later write that “looking back, we can see that the Depression nourished culture as it brought together artists, professionals and intellectuals. The catalyst was Jake, his shop the cultural heart of Los Angeles.”

When Huxley made the keynote speech to open Zeitlin’s new shop in Westlake in 1938, he recognized the importance of Zeitlin’s role as a catalyst. Writers were constantly attracted to his shop—William Saroyan had wandered in once and tried to convince Zeitlin that he should publish something of his, sight unseen. Zeitlin replied that he would be glad to publish something of Saroyan’s, especially if he could see it first. You never knew whom you might meet at Zeitlin’s shop, said Carey McWilliams. And as if to prove McWilliams right, Zeitlin was full of great stories about his brushes with such noteworthy writers as Steinbeck, Faulkner, West, Dreiser, and S.J. Perelman.

Zeitlin also knew Henry Miller quite well, although he was not an enormous fan of the man’s writing or of the man himself, who he dismissed as a rather commonplace and vulgar fellow, “a crumb with no social conscience.” Zeitlin’s views were confirmed by Josephine as well. Zeitlin agrees that Miller obviously had an outsized writing talent. He took Miller to talk to Huxley over lunch in 1937, and while everyone was cordial enough, the chemistry wasn’t there. Huxley later observed to Zeitlin that Miller reminded him “of a Sunday school teacher from the Midwest.”

Still, in the coffeehouse scene of the late fifties and early sixties, copies of The Air-Conditioned Nightmare were as much in view as Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn had been on display in hip circles in the thirties, forties and early fifties. That book, along with books by Kerouac, Ginsberg, Kenneth Patchen and Ferlinghetti, were the true voices of the beats.

*

It was getting late and we had been talking for several hours. Zeitlin was blunt in his opinions, and I was anxious for him to venture more of them. For example, I told him that I thought his friend Powell had treated Upton Sinclair, one of my favorite writers, rather badly. And I assumed the reason was politics. What did Zeitlin think? Zeitlin replied that his old friend Powell may be a wonderful fellow—he and Powell communicated regularly right up to the end— but Zeitlin nonetheless said “he had no political sense. Never had. He even endorsed Nixon once.” Powell died at the age of 94 in March of 2001.

Zeitlin also had little patience with my impression that great writers seemed to have vanished from the landscape. “I don’t think writing has gone downhill. I think publishing has. There were always chambermaid romances and dime-store novels. And I think that Mr. McLuhan made more noise than sense,” he added, dismissing the late Canadian media philosopher who in the sixties was predicting the end of literacy. “I don’t think there’s been a decline in literacy—although I don’t know where the literates are anymore.” He insisted that contemporary writers like Saul Bellow and John Updike must be taken seriously. “The writers of principle are still there, just as they always were.”

I was not entirely convinced, but I listened when he said, “There’s been a tremendous amount of ferment here, a lot of new enterprises, fortunes being made, and the material for a lot of crashes was also being made here. There’s a tremendous intermingling of cultures. The legend of Los Angeles has grown tremendously, and people believe in legends so much they don’t even compare the legend to the reality. Southern California has become a tremendously legendary place.”

Zeitlin played a big role in that legend, like the Los Angeles River, a strange river that sometimes flows with a terrifying intensity. Along the river and over the decades, people have written a lot of books about L.A. People often look at the Los Angeles River especially when it is dry in summer and make jokes about it. They’ve done the same thing with the city’s cultural life—they proclaimed it is a river that mostly runs dry. But the Los Angeles River is very much alive—just in an odd kind of way. You have to get to know it to understand it and treat it with respect.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.