Tales Of That Extraordinary Madman, Charles Bukowski

IN 1972, when I saw fellow Los Angeles Free Press writer Charles Bukowski’s book in the window of a bookstore in West Hampstead in London, my first reaction was one of jealousy The book was called Notes of a Dirty Old Man, the same title as his column in the paper. It was a City Lights book, with Bukowski’s amazing pocked alcoholic face adorning its cover. I viewed Bukowski as only doing a limited shtick – he rarely came into the office himself, but I knew all about him because my friend Judy Lewellen, the city editor, used to go pick up the column. I guess I hadn’t understood how popular Bukowski was getting until I was confronted by a book display in London. Years later, I came to realize that this guy had paid far more dues in his life than I had.

He was more than just a good offbeat columnist. Everyone knows about Bukowski, who for many years was able to walk the decaying, slummy streets of Los Angeles – as a mailman, a hobo, an alcoholic on Skid Row – while his writing was beginning to sell by the thousands – in Europe. He was especially popular in his native Germany. In the United States he was selling only in the hundreds. Bukowski was an ethnic Polish-German, but in the latter years of his life he did become famous in his hometown of Los Angeles. Even though the movie “Barfly” didn’t do well at the box office, it helped draw more attention Bukowski’s way. Mickey Rourke did a good job playing Bukowski, and Faye Dunaway was his girl. In an earlier movie, “Tales of Ordinary Madness,” Ben Gazzara also did a fine job of playing a slicked up Bukowski.

Let me tell you about the time I reconstructed Bukowski.

*

It was one of those rare moments when it really was impossible to figure out whether art imitates life, or life imitates art. The occasion was an informal, lightly-attended afternoon movie premiere of “Tales of Ordinary Madness” at a theater in West Los Angeles. “Tales” was an Italian-made film about a mad and drunken Los Angeles poet, based on various autobiographical short stories by Bukowski.

As the movie began, Ben Gazzara appeared on the screen taking a swig from a brown-bagged wine bottle. I turned around to see what the real Charles Bukowski thought of all this – he was sitting three or four rows back. He, too, was swigging away from a “freeway bag” full of wine in sync with the character on the screen.

Bukowski had lived in Los Angeles since 1923. His parents brought him to L.A. from his native Andernach, Germany, when he was two. For most of his young years he was an unknown: a day laborer, a postman, and, for more than a decade, an out-and-out Skid Row bum. He ended up with his stomach hemorrhaging at Los Angeles County’s General Hospital where the doctors warned him that unless he stopped drinking he would die. Characteristically, the minute Bukowski was discharged, he found a bar. He never apologized for his drinking; he reveled in it. “Two things kept me from suicide – writing and the bottle,” he said.

He began writing seriously in the fifties. “To have the nerve to attempt an art form as exacting and unrenumerative as poetry at the age of 32 is a form of madness,” Bukowski explained. “But crazy as I was, I felt I had something to say, as I had lived with degradation, and on the edge of death … what had I to lose?”

Bukowski’s poetry began appearing regularly in little literary magazines, but it wasn’t until the sixties that he came to public prominence with his raunchy, outrageous and often hilarious prose column, “Notes of a Dirty Old Man,” in the “underground” Los Angeles Free Press. “Notes” described the misadventures of Bukowski’s alter-ego, a fellow named Henry Chinaski. One woman after another hopped in and out of Chinaski’s bed. All this occurred on Bukowski’s turf, the underbelly of L.A., mostly downtown and Hollywood and various states in between.

The columns were first published as a book by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights in 1969. But most of Bukowski’s later books were published from the West Los Angeles garage of publisher John Martin, who issued Bukowski’s first novel, Post Office, in 1971. Anyone who has ever hated a job could appreciate this “Catch 22” of the workaday world. Post Office was the first Bukowski volume in which his unique, gut-wrenchingly lyrical style really began to emerge. Soon afterward, Martin moved Black Sparrow Press a hundred miles up the coast to Santa Barbara. He has since gone further north, to Santa Rosa and later after Bukowski died, sold it. But he kept publishing Bukowski for many years, doing close to thirty volumes of poetry and fiction, many of which have now sold many thousands of copies.

Bukowski’s reputation grew quickly in the seventies, especially in Germany, Spain, Italy, Norway, Finland and France. It did not grow so quickly in England or in his home territory – California.

Bukowski himself says he once spent three months in New York in the forties and came to the conclusion that “Maybe it’s a nice place now, only I’m not going to try it.” Even after his death Bukowski was more popular in Europe than the place he wrote about. “I can go into the supermarket and buy a dozen eggs,” Bukowski, who lived in San Pedro rather than Hollywood at the end of his life, remarked. “You’re not going to find a bevy of poets sipping espresso” in L.A.’s still primarily blue-collar port town. Why do they love him so in Europe. “It’s an older culture. The people…they know more.”

Bukowski evolved as a writer to the point where he could be compared to his cultural heroes, Henry Miller, John Fante, and Louis-Ferdinand Celine. Miller himself once called Bukowski the “poet satyr of todays underground.”

John Harris, when he was still the proprietor of Papa Bach Bookstore, used to insist that Bukowski was a terrible downer. “He doesn’t celebrate anything but his own stool.” Muns, who ran across Bukowski in his Hollywood wanderings on more than one occasion, opined “He’s good, I suppose, if you like reading about toilets and whorehouses.”

The San Francisco Chronicle, on the other hand, said, “Bukowski is pure Los Angeles – in the insane, exciting, frenetic, electrical sense of that whole incredible scene.” And the Los Angeles Times declared, “Bukowski is the most important short story writer since Hemingway.” The German newspaper Die Welt wrote, “Bukowski is what you’ll have to call the American anti-guru. He’s so authentic he can make you cringe.” And another German magazine proclaimed, “American nightmares. Very brutal, very honest, yet apocalyptic – and very funny.” Bukowski became a literary phenomenon before his death, and like Hemingway in his last years, the author himself became bigger than life. His legend was better known than his works.

One sensed this that afternoon at the Royal Theater as Bukowski moved slowly out of the lobby after the premiere of “Tales of Ordinary Madness.” Upon this, his first viewing of the movie, he seemed genuinely touched by it. As Bukowski passed through the theater, he stopped for a few minutes to warmly greet producer Fred Baker, who seemed relieved that Bukowski had liked the film. Baker was not a close friend of Bukowski’s, but a few nights previously he had gotten a rare invitation to visit Bukowski in San Pedro. Bukowski, Baker said, had treated him well enough – at first. But as the evening wore on, Bukowski continued his two-fisted drinking until he was becoming surly and even a littie threatening. Baker said that it was only when he got up to leave that Bukowski quickly seemed to regain some of his gruff, warm charm. When I told Baker that I was going to try to interview Bukowski, he warned me that Bukowski is a different kind of guy from the rest of us.

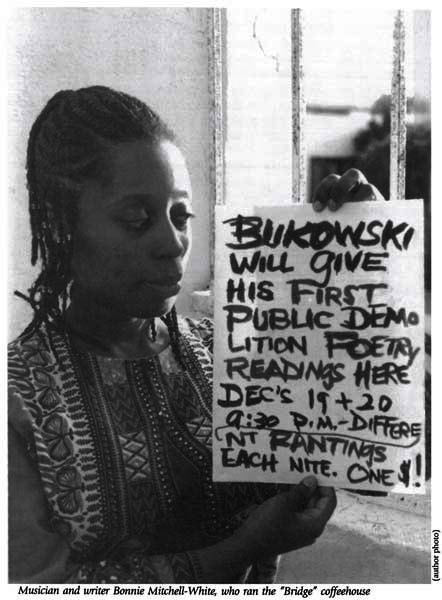

Even so, over the next several days, I approached Bukowski, by mail, by phone, and through intermediaries – and I talked to many people who had known him well at different points of his career. In a letter, I even apologized to him for having slighted him in my original Literary L.A., but nothing seemed to work – Bukowski, of late, had taken to turning down most interviews. His standard line was that everything is there in his books. “Make up quotes,” he told one would-be interviewer, “It’s all right by me.” Still I kept trying, hoping there might be someone Bukowski trusted who could convince him to make an exception for me. Instead, I found some of his acquaintances angry at me for even trying to interview him. “The recent waves of of attention are not good for him, because when he gets into uncomfortable situations he drinks even more than usual.” I was told by an admirer that Bukowski routinely turned down thousands of dollars for public appearances and that his last one was years and years ago when he said he would never do another one again – and didn’t.

Finally I was compelled to try to put Bukowski’s story together from all my interviews with friends and former lovers and such. But I was saved from this by one of the world’s greatest eccentrics, and a good friend of mine from the Xanadu. Gene Vier was the old newspaper and magazine staffer whom you would recognize you ever saw Detective Columbo on television. Actor Peter Falk used Vier as a model for Columbo’s appearance and demeanor. Gene is one of those rare people who either knows everyone in the world, or knows someone who knows someone. He didn’t know Bukowski directly; but a couple of his good friends, Laura and Frank Cavestani, just happened to be drinking partners of Bukowski’s. If I showed up at the official premiere of “Tales of Ordinary Madness,” being held at the Encore Theatre in Hollywood, Vier assured me I would get my chance at least to go out drinking with Bukowski – if not actually interview him.

The night of the official premiere was cold and rainy, and none of what unfolded seemed to hold much promise at first. When Bukowski and his girlfriend, Linda Lee Beighle, walked into the theater, the author was immediately mobbed by hordes of autograph seekers. Bukowski planted himself at a counter to sign books on which the movie was based; and before he began, he loudly protested and with mock gruffness referred to all his fans with a colloquial term for excrement, and then openly raised a bottie, covered by the traditional brown bag, to his lips.

Nigey and I later joined Vier, the Cavestanis, Bukowski and Linda in the rear of the theater, near the door. We were told that Bukowski might want to slip out early. I was also warned not to bring any tools of my trade, such as a tape recorder or a pen and paper. In fact, I was warned to refrain from asking interview-type questions, that is, about literature or modern poets or politics and such. (I already knew that the evidence about his politics was mixed – he was enamored of fascist writers like Celine and Ezra Pound, but Vier told me that he also admired Sartre and Marx). Just come prepared to observe what was going to probably be a night of vintage Bukowski, Gene had said. Bukowski had already been drinking heavily even for him that evening.

Perhaps because of all the alcohol he had consumed, or perhaps because there was a large audience of fans, Bukowski wasn’t sounding nearly as charitable about the movie the second time he saw it. I didn’t feel that it had worn well, either. Gazzara looked too much like a matinee idol to portray the pock-marked, alcohol-ravaged character who had become Bukowski’s trademark over the years. Vier suggested that the problem was that the film insisted on making Bukowski into kind of a saint of the dispossessed.

In actuality Bukowski didn’t want to be nominated for sainthood. So he played movie critic that night by shouting out his objections as the movie progressed. For example, during a scene in which a beautiful prostitute lay down on his bed, while the Gazarra-Chinaski character just kept typing at his desk, Bukowski yelled out, “If that were me I would have stopped typing long ago!” As a scene in a flophouse rolled by, Bukowski cried out that “I’ve never seen a flophouse as empty and clean as that one.” As a stream of such comments kept emanating from our corner of the theater, someone in the audience yelled at Bukowski to shut up. Bukowski replied, “Hey, I’m the guy they made the movie about. I can say anything I want to. You shut up.” Toward the end of the film, a woman strolled up the aisle past Bukowski and told him that she loved him but was bored by the movie. He responded by saying he would give her his phone number, but he was too drunk to get even that much accomplished. He kept asking Linda for a pen and paper, but she was not being very cooperative.

It was raining as if it were the end of the world when our entourage finally left the theater. We headed toward a bar several blocks away. This was familiar Hollywood territory to Bukowski. As we walked past the old Monogram Studios on Melrose Avenue just west of Van Ness, Vier was leading the way, but Bukowski caught up with him and put his arm around Vier as if they were long-lost friends. We couldn’t hear what Bukowski was saying, but he was obviously on his way to a state of total inebriation. We finally reached the bar but it was on the other side of Melrose. As we were lining up, waiting for a break in the rain and traffic, Bukowski suddenly made a dash for the middle of the street. He was choo-chooing drunkenly, going in circles like a locomotive on a fast track to nowhere, looking back at us yelling, “Hey, I thought you guys would follow me wherever I go.” A car was bearing down on him through the darkened, rain-slicked street, and Frank and Linda both ran out and dragged Bukowski back. Eventually we made it safely into the bar, a rather typical blue-collar bar with a loud jukebox, torn red vinyl booths and a pool table in the back. We headed for the rear where it was less crowded.

Nigey and I sat directly across from Bukowski, who began pounding on the table and demanding booze. Red wine appeared out of nowhere and more drinking began. A Judy Garland song from a 1931 movie crooned its tinny heart out on the jukebox. This occasioned a monologue from Bukowski about how he was a creature of the forties, “no make that the thirties, maybe even the twenties.” From there, his monologue made its way to some halfhearted comments about all the women troubles he was having: Bukowski’s books are always full of women troubles. None of this appeared to disturb Linda, who was sitting by his side, seemingly oblivious to this patter which she had no doubt heard many times before. “When I’m lying in bed and reach out, I like to feel nothing,” he grumbled. Then he told the story of Sir John Gielgud, the British actor who Bukowski said was married to a madwoman for 19 years. Whenever Gielgud mentioned a good review from the previous night’s performance, the mad wife – at least according to Bukowski’s pickled version – “would start to shriek at him to pick up his socks.” Bukowski ended his little yarn with a knowing look at Linda, but then he relieved the tension with a rather self-deprecating laugh. “Being married to the mad woman made him feel alive,” Bukowski felt he had to explain. He leaned over and kissed Linda, who didn’t look in the least mad but rather nobly patient.

Tired of us by now, Bukowski looked over to the pool table where a couple of working stiffs were playing. “The dead pool table of nowhere,” he said, pulling himself out of his chair and meandering over to their direction. From where we were, we could hear Bukowski trying to explain to the pool players that he was “a celebrity now, because a movie had been made about my life.” They might have been impressed had they understood English. But neither seemed to know what to make of Bukowski, even though he made it plain to us when he came back that he considered himself more one of them than one of us. He sat down again across from Nigey and me and said, “I hate intellectuals.” Thus we had our first encounter.

“I’m the toughest guy in town,” he said, looking right at me – the first time he would utter the phrase that would become his refrain in each of the three bars around Hollywood that we journeyed to that night. I made some sort of barroom reply, and Bukowski quickly backed down. We talked a bit, and Bukowski seemed to warm up. “You have an honest face, a good face, but behind it is a lot of bullshit, in the way you have dealt with people,” he said to me. This undoubtedly was true of most of us in this life, I replied. “See what I mean,” Bukowski rejoined, triumphandy. “All of mankind means nothing. Mankind is all cowardice. Has no courage. So let’s drink.”

Vier, meanwhile, had been sitting on the other side from Bukowski. With unexpected vehemence, Vier burst out that Bukowski was full of it. “Hank,” he said, “you can’t tell us that even in your own negative way, you don’t celebrate life. It’s there in your poetry.” Bukowski looked at Vier, and for the longest time I thought he was going to remain speechless. Finally, however, Bukowski said, “You’re a funny man.” A little later, he looked into Vier’s face and said, “You are a tormented man. Hey, man, I’m sorry I can’t make you happy.” His tone of voice sounded sincere, although quite drunken. He kept repeating to Vier over and over again, “Hey man, I wish I could make you happy. I wish I could make you happy.”

Not much more time elapsed before everyone agreed it was time to move onto the next place. We would go further down Melrose, to Lucy’s El Adobe, the Mexican restaurant made famous by Jerry Brown, the eccentric but significant California governor. Bukowski became more raucous as we moved on (still friendly but sounding more and more streetwise) and obviously felt it was time to say something. Vier again interjected, “Hey, Bukowski, for you life is a horserace. You’re competitive. I think it’s a dance. Remember style; don’t you hear those words of yours at the beginning of the movie, about everything being style. You’re handling stardom very badly, Hank.”

Bukowski seemed chagrined at the speech. It was a while before he responded. But in a few minutes, Bukowski was out of his seat and loudly demanding more booze. The management said no, which, of course, made Bukowski even angrier and more incessant in his demands. I jumped in with a compromise. I ordered three beers, and handed them to Bukowski. He quieted down for a while, happy with his liquor. Soon he was entertaining us with vulgar references and jokes about his and Linda’s sex practices. Then he suddenly eyed a group of big, muscular punks in the next booth. He cried out loudly, so that they could hear too. “Hey, look at the fags,” he said. “Look at the fags.” His voice rested awhile on the word fags. After a few minutes of this, he managed to succeed in getting what he wanted – he had outgrossed the punks; they left, muttering angrily among themselves and glaring at him out of the corners of their eyes. Bukowski really didn’t give a damn, even if they had come over to start a fight. But something told the youths to keep their distance.

By the time we finally got back to the parking lot behind Lucy’s, the trick had become getting Bukowski to stay seated in the rear of Frank’s VW. He didn’t seem angry at anyone in particular, just intent on getting out of the car when he had just finished getting into it. No one could keep him there. He was oblivious to the sheets of black rain as he insisted on climbing out of the car. Then he became very apologetic – if you spent much time around Bukowski, you heard a lot of apologies – and sat down meekly in the back of Cavastani’s car.

Cavastani drove Bukowski and Linda back to their car, and now there was a three-car procession through the rain to Dan Tana’s, next to the Troubadour, on the edge of Beverly Hills. It wasn’t long before the maitre d’ was inviting Bukowski to leave the premises again, as Bukowski obstreperously demanded booze. Bukowski looked at the waiter’s smooth face and said, “You have an empty face.” The maitre d’ came over and a compromise was reached – Frank would have responsibility for Bukowski, who was getting a little more subdued again.

Bukowski was generous. He bought us all a fine bottie of expensive red wine and got serious enough to first apologize for preaching, and then observe, “You guys are looking for a hero. I don’t want to be your hero.”

I thought of telling him that he was being a litde presumptuous, but I didn’t. Bukowski wanted to talk about death. “I’m 63 years old. I’m closer to death than any of you here.”

Then he looked at Nigey and me. “These people are going to be killed,” he announced in a sonorous kind of voice. I wasn’t sure if his tone of voice was supposed to be threatening – it was only the content that was. How do you know? I asked. “With bullets,” he replied. Again I asked him how he knew that. “I don’t,” he laughed. “I’m only a poet. I only know how to write poems. Other than that one thing, I’m an ignorant man.” Then he pulled back, and returned to the evening’s refrain. “Hey man, do you know I’m the toughest guy in town. And also the kindest.”

By now the conversation was lagging. Bukowski and Linda Lee were bickering. He’d throw oral barbs her way, and then make up by kissing her, or mussing her hair. Then he fell completely silent. He slid away from Linda, and chugged his way rather precariously to the bar.

“Oh, oh, I hope Papa will be OK,” Linda said with obvious concern. But “Papa” made it up to the bar just fine, and plunked himself down next to Cavastani, who was studying a racing form. We talked a while more with Linda and Laura, and then made our way up to the bar to say goodbye to Bukowski. He put down his racing form, and put his hand on Nigey’s arm and bade her farewell with an impromptu poem. Then he did the same with me. I bent over to hear what my poem was, but I heard only a phrase or two, and mosdy mumbling. Outside the bar, I asked Nigey if she had heard what her poem had been. She, too, had had the same problem – whether it had been poetic and sonorous she would never know, for it had been unintelligible. She did note, however, that the drunker he got, the more poetic he became. Probably, Nigey said, he was just summing up everything he had said all evening. I told her I wished I could have hard those summings-up. We also said goodbye to Linda, who seemed sad to see us go.

Several days later we walked into Sholom Stodolsky’s Baroque Bookstore which was on Las Palmas in Hollywood. We told Stodolsky, who has died since this was written, about our night of drinking with Bukowski, and about how he had begun damning us as “intellectuals.” Stodolsky, who knew Bukowski pretty well, said that was just “Bukowski playing Bukowski.” But then he told us that on the night of the premiere, police had stopped Bukowski and Linda on the way home from leaving Dan Tana’s. The cops just took away Bukowski’s keys and let him sober up because they knew who he was. I heard another version of the same incident a few days later. The second story was that when the cops found Bukowski, his BMW was on the sidewalk, and his face was scratched up – he and Linda had been fighting. The cops took his keys away, but sly old Bukowski simply took out another set he had hidden in his pocket; and he and Linda drove home. Both stories had an authentic ring, even if neither was a hundred percent accurate.

A while later Vier and I were again comparing notes about Bukowski. Vier said what made Bukowski fascinating to Europeans is that being down and out in Los Angeles is much more degrading and alienating than being down and out in Europe. Vier opined, in fact, that Bukowski’s down and out L.A. experiences were better literature than had been George Orwell’s in London and Paris in the thirties. Being down and out in a demi-paradise, where so many have so much, Vier argued, is to belong to nothing. In Europe, even the down and out belong to a class, and have their place in the society. “Bukowski’s style,” said Vier, “is pure Skid Row. It’s a style that was developed on the streets. When you’re down that far, style is all you have. There is no such thing as getting status through money – it’s all style.” Vier had actually discussed his idea with Bukowski, who had noted that many of his characters were people who “had one out – death.” Even though Bukowski had pontificated to me that “the middle class” has no courage, he had told Vier that he didn’t reject middle class luxury, “I only reject the price people pay to get it.”

And truly, Bukowski had mastered the art of good living. He wrote poems about how much he liked to drive his $30,000 BMW. Libraries and collectors seek out his special editions. Even his drawings are now collector’s items. Muns, who was as good a friend of Vier’s as he was of mine, owns a Bukowski original that was given to him a few years back by Larry Miller, a friend of Bukowski. Miller knew him primarily because Miller’s sister Pam was one of Bukowski’s girlfriends. The oil painting is a large childlike profile of what looks like an abstract cow, a rather strange apparition that Muns kept in his closet.

Like a lot of observers of the L.A. literary scene, Muns had closely followed the growing Bukowski legend. At one point, Muns had even come across Bukowski in the restaurant that Linda owned which was close to San Pedro. Muns said he was “wearing Picasso-like pants, checkerboard abstracts of a multicolored-thick material like clowns wear, with green suspenders.” Muns avoided going up to talk to Bukowski, but he remembered the first time he head seen him, when he was in much different circumstances. Then Bukowski was still living in a sleazy court near Western Avenue and Hollywood Boulevard hanging out with Pam Miller. “It was a small, drab apartment,” Muns recalled, “dark inside, the shades all pulled, no curtains, old furniture, newspapers. And first editions of his own books arranged on a crude counter.”

Pam, an attractive redhead, had taken Muns to visit Bukowski on that occasion. Last heard from, she was married to a lawyer and was a sales representative for a large title company. She had been Bukowski’s girlfriend in the mid-seventies, between Linda Beighle and sculptor-poet Linda King. Bukowski wrote a book of poems about Pam called Scarlet. She was also a character named “Tammie” in Bukowski’s popular novel, Women. Muns remembered that much of the visit was taken up with Pam and Bukowski talking about things that only they understood. Muns never became a big Bukowski fan, but still he conceded that Bukowski might ultimately end up being compared to Hemingway. “In his own crazy way, Bukowski is more of an existentialist, closer to the marrow of existentialism than Hemingway ever was.”

Gerald Locklin, who writes poetry in the Bukowski manner, won high praise from Bukowski. Locklin is a poet and English professor at Cal State University in Long Beach – despite this, Bukowski said that Locklin was one of the few modern poets he could stand.

Because of the voluminous correspondence that was carried on between them, the two were considered close. Years ago Locklin explained his mentor this way: “Miller said Orwell gave the proletariat a voice. I think Bukowski does this even more than Miller. He is a man who has lived at the lowest socioeconomic level, yet he can write realistically about it. Most social realism is written from the outside, by fairly well-educated people who may be temporarily sharing the lives of the lower classes, but Bukowski writes as one.” Locklin agreed that Bukowski is not obviously political. He quoted Bukowski as saying that “politics are just like women: get into them seriously and you’re going to come out looking like an earthworm stepped on by a longshoreman’s boot.” In Bukowski’s view, said Locklin, politics is mostiy “irrelevant, naive, wrong and ineffective.”

Now that I knew more about Bukowski’s politics, I wanted to know more about him as a man and a lover. After all, he was the one who called the column “Notes of a Dirty Old Man.” So I asked Muns to put me in contact with Larry and Pam Miller. Is Bukowski really a violent womanizer who loves them and leaves them, which he does in his books? The answer, according to both Larry and Pam, was: absolutely not. Both of them found Bukowski to be a soft pussycat, jealous and possessive of his women, “and needing women far more than they needed him.” He’s also a romantic, Pam claimed. When Bukowski was courting Pam and they were living apart, Bukowski would leave poetry in her back door whenever she hadn’t called him for a day or two.

“There was nothing at all violent about him – at least, he never exhibited anything violent in front of me,” Pam told me. Sometimes, she admitted later, they would have boozy fights and throw things at each other. They did that on several occasions, such as when they were eating at Musso and Frank’s in Hollywood, usually because he would falsely accuse her of having affairs with the postman, the milkman, and everyone else. When Pam knew Bukowski, he was just beginning to achieve financial independence – sometimes he would leave his uncashed checks around the house for weeks, where they would gather wine and beer stains.

Pam said that Bukowski was kind to her personally but very unkind in print. “He took a lot of poetic license. He always pictures himself as a Romeo living a lot more dangerously than he really does. Actually, he’s an extremely introverted, cynical, asexual kind of man.”

I asked how he would rate as a lover? “Well, he was a severe alcoholic in his mid-fifties so he wasn’t that active, even though he continued to write about his sexual experiences.” Still, she said coyly, “sometimes he was a good lover – I would give him a four-star rating.” She giggled embarrassedly.

He was also very kind to her. When she called and wanted a ride at two in the morning, he would always come. When she needed to borrow money, he was there. He was also very fond of her small daughter: the three of them used to go on regular outings during the week – to the horse races, or to the Olympic auditorium to watch boxing.

*

Pam (who later became known as Pam Brandes-Wood) thought for a moment when I asked her to sum up the man as best she could. She replied: “He’s a very deeply scarred soul. He has a lot of gentleness. He portrayed me as an airhead in his book; he was very unfair, but he wasn’t that way to me. The persona in the book is not him at all. But he’s not an easy man to get close to. He’s a misanthrope. He is reclusive; he values his privacy. He has experienced a lot of unpleasant things in his life. But he’s really not a misanthrope. Once you get past a certain point with him, there’s nothing he wouldn’t do for you.”

Shortly before Muns died we tried to find Pam. Someone who was writing a book on Bukowski asked me if I still knew where she was. I asked Muns. He tried driving by her brother’s house, but he was gone – no one knew where. And she was gone as well.

*

This is excerpted from “Literary L.A.” by Lionel Rolfe which is available in digital editions through our website.