“Our Own Kind” by Umberto Tosi

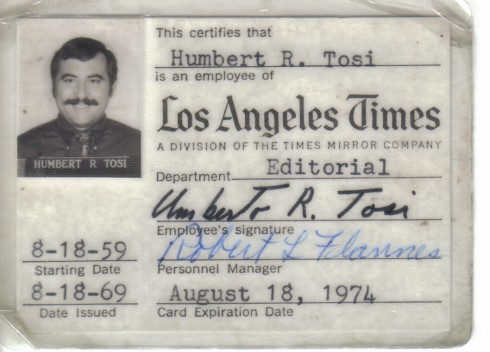

The story takes place in Los. Angeles between the assassinations of MLK and RFK. But is is PURELY fiction. a RUMINATION. The author, Umberto Tosi, modeled characters, situations and events on experiences — personal and professional — during his decade as a writer and editor at the Los Angeles Time during the 1960s and early 70s.

It’s not an attempt at expose, or investigation, more a musing on personal vectors with history, the inner reverberations and considerations experiences by — after all — ordinary people surviving near the ground zero of social and political tragedy and cataclysm, and the interplay of race and culture with same.

Boryanabooks will serialize the book over the next several issues.

Umberto Tosi (aka Nino Tosi) Then and Now

by Umberto Tosi

Copyright©2012 by Umberto Tosi

– all rights reserved

1. RED ALL OVER

Damn florescent lights keep flickering, just like the one over his desk back at the Times. All this white could make him invisible. Bleached walls, tiles, curtains, bedding, pale as his ghostly face, set off against his black silky Sy Devore shirt and the dark droplets of blood peeking from her bandages that worry him. Air conditioning blows soundlessly from vents above, morgue-cold in this sterile space, once removed from the smoggy heat of this June morning in Los Angeles. This summer, not of love, 1968, will be very long.

Makeda’s monitor beeps in reassuring syncopation with the wheezy snores of a curtained-off roommate. A muted TV oozes soap opera from high on a wall opposite her bed. Makeda hates TV, and would loathe that her picture – a dated, inappropriately smiling high school yearbook shot – keeps showing up on network news, and in the papers, though only below the fold now.

Gingerly, Ben takes Makeda’s limp hand, careful with the IV tube. He whispers her name. She breathes softly, unresponsive. The little girl next to Ben stares up at the television screen for a while. She holds a small bunch of droopy spring flowers wrapped in greenish paper. Benny bought them for her to give to her mother. The girl pulls on Benny’s sleeve to change channels – find cartoons. He puts his finger to his lips and whispers that mommy is asleep.

The girl steals glances at her mama’s face, its familiar, normally radiant, sienna tones gone to dun against white pillows. That scary, odd, clear plastic straw thingy running under mama’s nose looks buggy, or Martian.

The girl can’t see much else but mounds and folds of blanket that look like the Hollywood Hills she saw from the back seat of Benny’s car on the freeway coming here. The girl looks down at the big rubber wheels of mama’s metal bed frame. She imagines Mr. Toad taking the bed on a while ride through the dull corridors of this place she doesn’t want to say is a hospital.

The little girl slips her hand from Benny’s and sits in a visitor’s chair. She puts the flowers down on a side table and picks up a magazine with pictures of pretty white women she doesn’t know. Her pony tails bounce adorably from red scrunchies as she flips pages. She swings her feet showing off her new red sneakers and matching knee socks with yellow flowers. She likes that Benny let her wear her new dress today – all in bright colors just like mama’s.

She likes Benny’s porcelain whiteness, accentuated by his all-black attire – jeans and silk shirt open at the collar. They make quite a pair, him all lanky like a Halloween skeleton. People look, and notice her pretty colors, and she skips and tilts her head this way and that when they do.

She wonders when mama will wake up so they can leave this place with its smells like rubbing alcohol that remind her of getting shots, but with no lollipops.

Benny presses against the bed and takes Makeda’s hand, careful not to disturb the IV. The warmth of her palm heartens him. He even catches the familiar, buttery scent of her through the hospital’s bitter medicinal odors. He wants to kiss the softness under her chin.

Makeda opens her eyes, glassy, trying to make out shapes. “He’s been shot.” She tries to cry this out, but it comes out a raspy whisper.

Benny squeezes her hand gently. “I know. It’s okay. You’re safe. You don’t have to talk. The nurse said your throat would be a little sore after they pulled out the tube.”

She squeezes Benny’s hand back. Her eyes widen as his face comes into focus. He doesn’t tell her that he didn’t like the nurse’s graven look or what else was said.

The little girl slides off the chair and stands on tip-toes beside the bed again. Makeda bends her head painfully forward to see.

“Oh my God, Keesha! Hi baby.”

“Hi mama.”

Benny lifts her awkwardly to the crook of his arm. He braces when she reaches out, nearly toppling onto her mother. Benny slides the girl onto the bed, so she can sit cross-legged on the edge, next to her mother. Makeda touches her daughter’s cheek, her hand trembles.

“Mama is so happy to see you, my darling. You okay?”

The little girl nods and smiles, worry in her eyes for the first time.

Makeda rolls her eyes over at Ben. “Really? Here?” Her rasp turns to whisper, but she gets her point across.

“I thought…”

“You thought like, let this poor child see mama. Well, mama’s not dead yet.” She manages a smile at her daughter.

“She’s been asking about you, about where you are. She’s seen your picture on the TV.”

“Jesus!”

“Just for a moment.”

Makeda lifts her head, trembling, and manages a smile. “You ought to be going to school now, baby. Mama’s going to be just fine and come home very soon.”

She looks at Ben. “What day is this?”

“Friday.”

She squints. “Three days?”

“Two and a half.”

She looks back at Keesha. “Don’t fret, sweetheart. They fixed me all up and I’m just about better.” Her voice trails off.

Makeda strains towards the girl She whispers. “Kiss. Kiss.”

The little girl puts her arms around her mother’s neck and kisses her cheek. Makeda kisses her back. “Mama loves you, baby, very much.”

“We should go now. Let you get some rest.” Benny goes to pick up the little girl.

Makeda pulls his hand again, stronger this time. “Benny…”

“She’s doing fine, don’t worry. I’m taking time off work and my girls can help us tomorrow, and Sunday when you get out of here, I hope.”

Makeda coughs, takes a breath and rasps softly again. “Ben. Thank you for this. Are you okay?”

“I’m fine. And Keesha’s doing great.”

“Is he, you know… Did he make it?” Makeda raises her eyes to the TV.

Ben shakes his head.

Makeda mouths a word she doesn’t want her daughter to hear, then looks back to little Keesha. “You go with Benny, now, honey. Mama see you soon. Okay? You be good now, Keesha.”

Ben raises Keesha to kiss her mother goodbye, and squeezes Makeda’s hand again. He leaves holding the little girl’s hand. She waves back at her mother one more time. Benny checks for the guard. Gone.

——————-

2. SIREN SONG

Six months earlier. New Year’s day.

Ring, ring, ring! Goddammit! Who’s that this early – barely light? The phone won’t stop hurting his head. It pings, with sadistic merriment, off the bare hardwood floors and sparse furnishings of Benny’s rented cottage. The place is a real find, just below Mulholland – well positioned for the next brush fire or mudslide. Chipped, Spanish stucco and red tiles, once a guesthouse on an estate that belonged to Charlie Chaplin, now subdivided, a cozy three-bedroom. It’s raining, hard at the moment. They said ’68 would be wet. That’s L.A. – drought or downpour, fame or famine.

Benny pulls a pillow over his face and calculates whether he can reach and yank the phone from the wall. No rest for the wicked. The pillow doesn’t muffle much except the downpour spattering his windows.

Shit. He throws back his twisted blanket and lurches for the phone. He is goose-fleshed naked and New-Year’s-Day hung over, both conditions indulged form his still-novel single life, which alternates with weekend daddy-hood. No score in the first quarter.

The ringing stops before he can answer. Damn. Benny sits back on the saggy edge of his bed. Too awake now to recapture his dreamless sleep. He could dash outside onto his tiny patio and catch raindrops on his party parched tongue. He used to do that. It wouldn’t wash away the sour taste of this morning. He remembers why he hates parties. He tells the sparrows twittering in the wind-whipped date palm just outside to shut the fuck up! It’s January and gray as my prospects.

The phone starts up again. Fuck it.

No robe. Benny pulls the top sheet over his shoulders and pads out to the kitchenette.

I’m the Sheik of Araby.

All the girls are crazy ’bout me.

He cuts his thumb opening the coffee can. He turns on the tap and watches blood turning pink in running cold water until the bleeding subsides. He puts on the percolator. Can’t find cigarettes. He grabs a yellow-and-red peace-sign mug from the cabinet. No cream for his coffee, he uses a splash of the kids’ leftover chocolate milk from the fridge. It will do.

The phone starts up again. All right! God damn it. It’s red – Hello Nikita! Sorry, but we’ve had a little mix up with our nukes over here… Ben now has a good idea who is ringing him. He’s been slow to give out his new number, but Lori knows it from when he had the kids last week.

He picks up on the fifth ring and fakes a wide-awake baritone.

Lori doesn’t sound hostile or blitzed for a change, but edgy and small. Oh, shit. Maybe something’s happened with the kids. Should have answered sooner.

“Uncle Phil died.”

Silence, then he hears Lori putting down the receiver, coughing, yelling at her mother, crying, then picking it back up.

Poor Uncle Phil, funny man and the only sane one in her family. “Sorry to hear that, Lor. I know he meant a lot to you. Shit, he wasn’t that old.”

“Heart attack.” Her voice quavers.

Uncle Phil owned a hardware and feed store up in Redding. Lori’s mother is his sister – blonde, bright and a knockout – took a Greyhound out of their woodsy hometown for Hollywood soon as she turned 16 and became Gwen Fox, bit actress, then bombshell of her brief day, in a few forgotten movies that show up in art house retrospectives.

Along her way to stardom, Gwen worked nights as a leggy hat check girl at the Brown Derby, and mimeographed manifestos for the Socialist Workers party by day. That didn’t keep her from marrying oil fortune playboy David Granville III and becoming Cinderella to the tabloids.

She was over for Granville’s age limit by then, but it was true love until he got bored and went back to teen nymphs pimped by his valet. His lawyers settled quickly in private to avoid another paparazzi feeding frenzy, or worse – considering possible charges. Lori walked away with a considerable fortune — by her standards, though not by his. By then, the studios had found a new bombshell. Nobody would take her seriously as an actress, despite her underrated acting talent.

Plus, when she split with Granville, Gwen was already pregnant with Lori. Nothing was said about this. The lawyers had photos of her with another man, Sean Bliss, a part-time actor, screenwriter and radical leftist cohort from the old days.

Lori got his surname, plus a half sister, Nola, favored by her daddy and by providence with stunning good looks.

Bliss made a perfect red witch hunt target. Never a man of good judgment, he had even once gone to Stalinist Moscow to attend a solidarity conference. It was a free trip. He was young and curious.

When Lori was twelve, she returned home from school one day to discover that her presumed father had chosen to answer a House Unamerican Activities Committee subpoena in a Cadillac de Ville belonging to Lori’s mother, garage door shut, motor on, garden hose from tailpipe to window.

In need of a tune-up, the Caddy’s motor kept dying instead of Mr. Bliss. No problem. He put a Walther P38 in this mouth and pulled the trigger.

When young Lori smelled fumes when she returned to their rambling split-level house in Topanga Canyon from school. She heard what she thought was a backfire. She walked back through the kitchen and checked the garage. Lori remembers nothing except the blood splatter on the car windows. She fled back through the house, vomiting and locked herself in her room.

She hunkered on the floor behind her bed at the commotion when her mother arrived and called an ambulance. She didn’t respond to her mother’s pounding at her locked door, then yelling about Lori somehow being to blame for not calling for help, as if it would have mattered. Thenceforth, mother and daughter never spoke of this.

Now, Lori’s phone call to Benny on this New Year’s Day reminded him of when he met Lori. Both of them 18, it was at a New Year’s Eve party on her mother Gwen’s estate attended by various Hollywood luminaries and hangers-on. A press agent had invited him offhand, Ben being the B-list as a part-time art film reviewer for the Times.

Ben could see that Lori didn’t fit with this crowd. She stayed out in the kitchen mostly, helping with the caterers with snacks, and getting glares from her mother. Lori didn’t react as if Ben were Casper the Friendly Ghost or a zombie, just a cool, different-looking guy.

Ben drew Lori away. They drifted around the grounds and down to the swimming pool overlooking the bejeweled vastness that is Los Angeles on a blessedly clear winter night, spreading outward, diamonds on black velvet. They kissed and played around, and stripped down in the chill air for a giggling plunge into the steamy turquoise warmth of the kidney-shaped pool, secluded from the main house by a stand of cypress. They played like dolphins, silky skin-to-skin under water stirring vapors rising from its heated surface, hardly noticing the stroke of midnight – a muted affair as experienced from high in the Hollywood Hills, marked by distant sounds of car horns and far off fireworks.

They made alternately clumsy and breathy love, dried off then talked and talked, baring their souls with the fervent, earnest naïvete of youth determined to do it all better than their parents. It was her first time, not his but he was hardly more experienced. She didn’t mind his albinism, commented on it directly in passing when they talked about their growing up, a good sign. She seemed to enjoy sliding her hands along his long pearly body, but then holding back instead, with the awkwardness of a young girl who thinks herself homely.

Star-struck, thinking-with-your-dick damn fool, he thought to himself now, nine New Year’s Days later. Regret had replaced romance, this followed instantly by guilt for regretting what had lead to the births of his two darling, ever-present daughters.

Lori’s voice wasn’t helping his hangover. He sipped coffee as she inched her way to the point. “I’m going to drive up to Redding for the memorial and to take care of his affairs.”

“You buried the lead.”

“What?”

“Nothing.”

Uncle Phil, as he had promised, left Lori a comfortable inheritance, including his tidy, craftsman house on Shasta Lake outside of town.

“Okay. Great then, I’ll come by and pick Linda and Nicole. Pack them some extra clothes. I’ll see they get to school while your gone.”

“They’ll be fine with my mom.”

“No sale, Lori!” Contentiousness and mistrust had not abated, going into a second year of awkward, joint custody.

“No. It’s all arranged. I’m leaving today.”

“What the fuck? You can’t just do that without checking with me, Lori? I am their father. They should stay with me.”

“Don’t start. Mom insisted. I can’t deal with mom and you at the same time.” Gwen’s open hostility towards Ben since the divorce wasn’t news. The whole family, except old Phil, seemed to possess an insatiable appetite for drama.

At least Lori sounds coherent. No talk of aliens or the CIA transmitting to her over the television, or of doctors and nurses in the psych ward conspiring against her.

“Look, Lori. I don’t want to argue. Just bring the kids over or let me pick them up.”

More silence. Ben wants to slam the receiver down. If it weren’t a holiday he’d just call his lawyer.

Lori pipes in, her voice softer now. “Benny.”

“Yes.”

“I was thinking that if the girls stay with my mom, you could come with me, to the funeral. I know you liked Uncle Phil. We could spend some time together. We never seemed to have time for each other at the end.”

“I can’t.” I won’t. “I got to work. Busy as hell down at the paper.”

“Uncle Phil left me his house and everything, enough to get by without my mom or anybody’s help. You could write. We could bring the kids up there, put them in school in the fresh air. You could work for the local paper. Think of it.”

Benny flinches. He remembers their fleeting days of bliss – wannabe hipsters in black turtlenecks cruising jazz clubs, poetry readings and critiquing half-understood art movies. Then a careless pregnancy – but they were young, had high hopes just like JFK said. They’d raise kids the right way, with Dr. Spock’s help. Benny quit school and got the paper as a copy boy working the swing shifts. Wide eyed, baby parents: The doted on Linda’s every gurgle. Benny, uncomfortable in his uncertain cheap white shirt and regimental tie played journalist and aspiring film critics. Then it all unraveled in ways that Benny did not see coming – or chose to ignore – until Lori’s first blackouts and suicide attempts.

Benny flinches. He remembers their fleeting days of bliss – wannabe hipsters in black turtlenecks cruising jazz clubs, poetry readings and critiquing half-understood art movies. Then a careless pregnancy – but they were young, had high hopes just like JFK said. They’d raise kids the right way, with Dr. Spock’s help. Benny quit school and got the paper as a copy boy working the swing shifts. Wide eyed, baby parents: The doted on Linda’s every gurgle. Benny, uncomfortable in his uncertain cheap white shirt and regimental tie played journalist and aspiring film critics. Then it all unraveled in ways that Benny did not see coming – or chose to ignore – until Lori’s first blackouts and suicide attempts.

“Hello? Benny? Are you there?”

“Yes.”

“Will you drive with me up there?”

“I can’t. You know. My eyes. No night highway driving.” A transparent dodge: he’s perfectly able to drive under all conditions. Lucky for him, with his type of albinism involves no ocular disability. Medically, his condition is called hypomelanism, a partial lack of melanin, accounting for his alabaster complexion, but deep blue, not weakened, pink eyes. But he doesn’t like to discuss such details, even to those close to him, well aware of this engendering mystery, and maybe even liking it. Better to be a man of mystery than a medical freak, he told a shrink once, who had urged more openness.

Recklessly, perhaps, Ben had talked to Lori about the details – and about the delicate matter of heredity only after Lori got pregnant – not that there was any choice except a back-alley coat-hanger affair. The doctor told them what Benny already knew. Chances of passing on the recessive gene in a “mixed marriage” were as remote as it popping up from the union of two “normal” parents.

His partial albinism could disqualify him from military service, had he been drafted, but college, and then Linda’s birth got him deferments.

As antiwar protests escalated along with the war, he had told everyone he’d sooner go to Canada before Vietnam, a moot gesture. He burned his draft card at a party. It got him a few laughs, nothing else.

Benny cradles the receiver with his shoulder to pour coffee. He pushes Nicole’s dolls aside to make room for himself on his garage-sale, sea-foam Naugahyde couch. They keep talking.

Got to pee. He puts his cup on the coffee table and drags the phone with him to the bathroom, pulling its tangled line taunt. He has to sit on the toilet, door open, leaning forward to keep the receiver to his ear. He can flush after the call – not from modesty. He just doesn’t want to let Lori in on any aspect of his private life ever again. Enough she gets the kids to report on him.

Lori goes on about the trip to Redding, and the vision of them re-settling there, a dream Benny knew from experience could flip negative into a horror show at any moment. “Lori, I told you I can’t.”

“You mean you won’t?”

Pause. “That’s right, Lori. I won’t. No, no and no! Please don’t ask me again.” He finishes and returns to the living room area. He sips his coffee, tepid now, bitter as his guilt for exploding at her needlessly, but going on anyway. “You left me, remember. Not that it matters. It just won’t work with us. Let’s leave well enough alone.” A better man would step up – the mother of your children needs you, for better for worse, and all that. The coffee’s acrid and burns his lips.

“It could be so much better, Benny, with a house of our own up there.”

He thinks of himself exiled. I could write every day – go crazy right along with her, go crazy – call my confessional novel, Folle a Deux. Our double suicide could make it a bestseller.

“I feel bad, Lori, believe me. But I can’t do it just up and leave. I have assignments.” Not the real reason. Actually, he’s grown to hate his job. I’m a coward. Benny pushes the receiver hard against the side his head. His ear feels hot.

“You mean you have girlfriends to screw, you fucker!” Lori’s flips from meek to manic.

“Here we go again.” Welcome to crazy town. “Sure, Lori, if you say so. Fuck yes! And oh boy! All I do is screw starlets. Orgies every night! I’m a regular Hugh Hefner. You should see the pair of New Year babes I got here right now.”

“Fuck you, Benny. You never loved me. You fucked my sister; you fucked Viola. ”

“Oh sure. There we go! Viola, Viola, Viola, all that nutty jealousy of yours! Hello! You had a dream that I was with Viola, Lori. You woke up and started screaming at me. But it never happened.”

But I wish it had. Viola Sabroza, jazz samba diva who lived next door to Gwen, a man would have to be far gone not to catch his breath in her presence, women too. Her daughter Ella played with his daughters.

“I know what you’re doing Benny!” Lori’s all-purpose accusation failed to evoke Benny’s natural guilt anymore. “I hate you! Fuck you.” She hangs up.

“And a happy, friggin’ new year to you too, Lori,” he says into a dead phone.

Same old, same old: Nothing new about this kind of exchange — but this time Benny senses finality in it, a threshold crossed before it could be noticed, the door back into his marriage slamming forever shut. No more chances to mend – and he wasn’t sorry, only saddened. Closing that door brings relief, freedom, but not release. He could never detach himself from their daughters, which meant he could never insulate himself fully from her. Some new accommodation would have to be found, not apparent or even conceivable to him at this point.

Benny sinks head in hands. He seethes against her wall of resentment and suspicion, her stubborn self-destructiveness. He knows the heart locked away as well. He realizes that she had opened the gates for one moment with her offer and that he had broken that heart, once again, with his unequivocal refusal.

He feels queasy, not noble. He had responded viscerally, without hesitation. He had not considered her as once-his-wife or even as human being, nor their children, nor practicalities, nor even his own desires. He had seen fire and rushed for the exit in unseemly self-preservation.

He dials her back. “Forgot to ask you what time I can pick up the girls? I’ve got extra clothes for them here, enough if you need to stay a week or so, and I can bring them to school until you get back.”

“Fuck you.”

“Did you tell them?”

“You’re not picking them up, Benny.”

“Hell I’m not.”

“My mother can take care of them.”

“That’s not acceptable. The order gives me joint custody. I’m their father.”

“Fuck you. I’m leaving today. I’ve already dropped them at mom’s house.”

“Don’t do this, Lori.”

She hangs up again. No calling back this time.

Ben slides a recording from the shelves where he keeps his collection – that and the stereo being the only items he took besides his clothing, when ??????split with Lori. He removes a 1929 shellac of Duke Ellington’s Black and Tan Fantasy from its jacket. He likes the weight , how the light reflects off its ebony surface and its burgundy and gold RCA label showing Nipper, head cocked to “his master’s voice” from a brass, Victrola horn – the terrier he always wanted when he was growing up dog-less with his single mother in Hollywood playing on a spinet after school dreamy.

He sets it gently on the turntable, carefully, no telling how many plays left on its scratchy surface. Arthur Whetsol’s poignant horn fits his mood. Somehow reminds him of Uncle Saul – on his Jewish side – occasional studio violinist with a rundown music shop on Fairfax, where Benny helped after school, paid, mostly in recordings Saul would fish from boxes in the back. He never knew what – symphonies, opera, jazz, Caruso, prized Rachmaninoff and Busoni performance originals, Mary Garden, whom Saul hinted richly, having romanced once when she toured Europe. Uncle Saul never talked about the numbers tattooed on his forearm. Benny learned about such things later.

Ben grubs a half-smoked Pall Mall from an ashtray, collapses on his sofa and listens to the rain – breakfast of champions. He picks a half-crumpled letter off the coffee table and reads it for the fourth time.

More than a perfunctory rejection slip – chatty from his old pal Roger Zwick under a Rolling Stone paper-boy logo – but disappointing nevertheless. Why keep reading it? He feels the generational pull, more on the political than then mind-altering side, grooving like everyone, with the latest Revolver and Magical Mystery Tour albums – others.

Just make the music – any kind – real, and not manufactured, or histrionic. He had enough of that. Benny was at the Whiskey A Go Go on the Strip when they shut down Jim Morrison for screaming, “Mother I want to fuck you!” He had the Doors album, and grooved on it, “but that was bullshit.” Benny imagined a time machine parked in his garage, awaiting repairs, jazz being prematurely declared dead as of the go-go sixties. “It’s just not my time. Don’t belong even with those who say they don’t belong, not turning on, tuning in or dropping out, not standing brave on the barricades, not with it, man, but never “regular” either, certainly not GI Joe. John Lennon’s Nowhere Man, that’s me. But I move with Monk and Coltrane and cool Miles to go before I sleep.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.