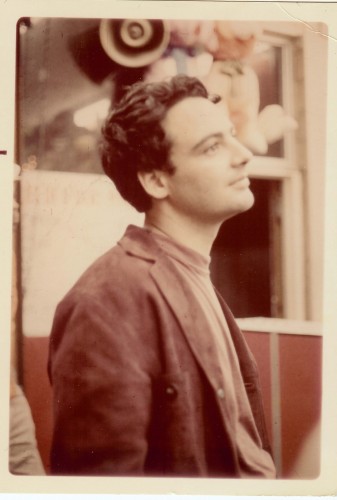

ONCE BEFORE I’VE SEEN THIS

The Author As A Young Man

By Stanton Kaye

© Stanton Kaye, 2014

Communication may be more of an art than a science:—Some people take no account of what’s being said, so we can say they lack the appreciation of the art.

My father was just such a person;—indirectly through a business associate, a Mr. I. Lugosi, who was selling him sweaters from Mexico or China—wholesale—at the time. The associate, Mr. I. Lugosi, operated (usually retail) from a small double storefront located just across the street from the Dupar’s side of the Farmers’ Market on Fairfax Avenue.

I was only sixteen. It was the fifties in Los Angeles and the early and late migration of Jewish businessmen liked to live in the proximity of a lot of Kosher amenities. At the time, this part of town—including the C.B.S. TV crowd—was like a pickle barrel of amenities from butchers to bakers; from Deli owners to deal makers; from Rabbis to ruminations on Zionism; yet my father still had room to swim between the pickles, so to speak:—That was maybe the most important thing about his business, perhaps more than profit margins.[1]

And so when my father met Mr. I. Lugosi, who sold him sweaters, they became friends; for Mr. I. Lugosi, although recently arrived to Fairfax from Budapest, was in his early sixties and wanted to teach my father, in his late fifties, either how to appreciate the arts or how to sell more sweaters at farm auctions to farm workers, or both. Two things were certain: they liked each other and they trusted each other, at least at this time.

Mr. I. Lugosi was slender and handsome, and though he had a heavy accent he said funny things in English clearly. My father said Mr. I. Lugosi was displaced by wars and Russian oppression, but before that he had been very wealthy; and, in the 1920s, when he was just a young man, he had used his money to support the artists in Paris in Monmarte near the Sacre Coer church, just above the Red Mill, near a section now called Pigalle.

So thirty years later when Mr. I. Lugosi’s rent on his sweater shop was due, he understood the necessity of paying rent very well; and my father, a former actor, director, writer and expert- on-where-to-sell-farm-workers-torn, faded-clothes-and-imported-sweaters-in-southern-California was asked to go along.

Mr. I. Lugosi’s landlord, Mr. D. Durst, was sick and he telephoned and asked Mr. I. Lugosi if he wouldn’t mind driving down near Pico Boulevard to his “after-the-Spanish- designed” duplex apartment—it was just five minutes by car down Fairfax Avenue and still in the area of amenities.

If you were a New Yorker and lived in the West 80s or 90s, it was like walking to Zabar’s, or better, biking there—nobody’d mind. And so these two, my father and Mr. I. Lugosi, who took cash, went down to Mr. D. Durst’s to pay the rent—and that’s where this story starts.

Somewhere once in the twenties or thirties, the Picfair Theater was a dream palace. It either stood for Pico and Fairfax, where it was situated, or for Mary Pickford and Douglas

Fairbanks, where it was situated in your mind.[2]

On a street just west and north of the Picfair Theater, Mr. D. Durst’s wife, a short but pretty little European lady in her seventies with her long gray hair pinned back in a bun on her head, was smiling in a paisley purple dress as she let Mr. I. Lugosi and my father through the door of her upstairs apartment.

She pointed to the bedroom through a hallway. Mr. I. Lugosi took the lead and my father waited outside in the living room. The apartment was dark. Mrs. Durst asked my father if he’d like some coffee or something to drink and my father declined. Would he sit down, she said and he did, in an arm chair by a couch. On a near tea table, she turned on a light—a harlequin that was exquisitely art deco—and went back to the kitchen. He could see Mr. D. Durst as Mr. I. Lugosi had left the bedroom door open down a hallway. Mr. I. Lugosi was already talking with Mrs. Durst’s aging husband; he was propped up in bed next to a faint yellow bedside light.

It turned out it was just a bad hip, and Mr. D. Durst was more immobile than terminal. Still, Mr. D. Durst was in his mid-seventies (although my father was a little overweight, had a bad back and was slightly out of breath from the steps, he and Mr. I. Lugosi were far younger men at the time). Mr. D. Durst probably was wealthier than the two men together, but he still enjoyed managing his properties. Real estate was a good investment back then—and who knows to this day that Mr. D. Durst didn’t in fact own everything Mr. and Mrs. Gilmore didn’t—the tombstone place, the Picfair Theater, Henry Roder’s novelty shop, “The Bagel,” etc.—even the Carthay Circle that still towered over everything back then just as Mr. C.B. DeMille wanted it to.

Mr. I. Lugosi gave Mr. D. Durst an envelope of cash. Mr. D. Durst looked inside but then noticing my father, he put the cash on the bed table next to some medicine without counting it. He looked through the door again and asked Mr. I. Lugosi who his friend was.

Before Mr. I. Lugosi could answer Mr. D. Durst called down the hall to my father, “Come in, young man.” What made Mae West want him as her leading man in the days of Vaudeville? Who cast this fat man with thin legs in Simoon opposite Ethyl Barrymoore—when he was thin forty years before in New York City in Greenwich Village? My father, definitely now graying, awkwardly sauntered, or staggered, into the room onto Mr. D. Durst’s bedroom stage.

Amazingly in the dim light from the single reading lamp, a twinkle occurred in everyone’s eyes. Mr. I. Lugosi had it. Mr. D. Durst had it. My father had it.

“So what are you doing here with the great Mr. I. Lugosi?” Mr. D. Durst said.

Before my father could answer, “Have you come to make sure he pays me fairly?” Mr. D. Durst said.

“I was told not to worry about money here, so I’ve only brought a joke, but I can go down to the car and get some money . . .” my father said.

“No, no I have plenty of money, but I’ve not heard a good joke in a least a week.” They all laughed. At which moment my father told this joke:

“Once there were three tailors who were sick in a hospital. One tailor to not be idle began to knit a shawl for his wife to keep her warm. The second tailor seeing this and thinking it was a good idea to keep busy, began also to knit, but he made a hat to keep his own ears warm at night. The third tailor who was not as smart as the others also began to knit. He worked on a shroud. All of them eventually got better and left the hospital.

“The first tailor of course received a good night with lots of love and kisses from his wife for the shawl. The second tailor never again had cold ears when he slept at night. But the third tailor looked at that shroud, every day, until he finally died: Never once did he think the others had picked the right market.”

Mr. I. Lugosi burst out laughing, Mr. D. Durst smiled and chuckled. My father laughed, too. This was not a joke; it was the bitter truth made sweet. My father had made it up on the spot! Mr. D. Durst called to Mr. I. Lugosi, pleased, “Tell my wife to bring the Kirschwasser in, please,” he said with a smile.

A decanter appeared in the faint light, carried by the wife.

“Are you trying to kill my husband here?” she smiled.

“You won’t get out of paying the rent,” she smiled.

Everyone laughed again, and had a drink, maybe two drinks. Small talk followed, about children, families and dinner. Everyone wanted to stay but had to leave.

Mr. D. Durst liked Mr. I. Lugosi as a tenant and a friend and he seemed to like my father.

“Mr. Kirsch,” he said, as that was my father’s name, “I know you have to leave, and we might not see each other ever again.”

“Well, you’re not dying. I’ll see you again I’m sure,” my father said.

Suddenly serious, Mr. D. Durst interrupted, “I’m old and wise, Mr. Kirsch, despite your good intentions. Sometimes you never see people you like more than once in this fast paced modern world. I’d like to help you.”

“I have a business . . . I make a living,” my father said, looking down at his fraying sweater (there were a few gravy stains). Then he realized his work pants were not gabardine, that his old gingham gray wool sports coat was ten years out of fashion, though it was Forstman wool and cashmere—but with lots of patches. (These were his “work clothes.” It was an “outfit” or some other excuse.)

“I do just fine, thank you,” my father said. He was lying. He looked one step up from the street. He was in these work clothes and they were meant to withstand the dust from farm fields; the sharp pips from cut shipping cardboard; the rain; the mud; the abuses of tiny nail heads from crudely-finished-counters-for-loosely-piled-“close-out”-women’s-blouses-and-bras that fecklessly adorned his storefront operation in Echo Park—where “Ecce Homo” gave way to “Buenos Dias, Boss,” to “Steek ‘em up!” at night.

(A good friend, who didn’t have the money for a main street Sunset Boulevard shop like my father’s took another store just a few doors off the Boulevard, near the Aimee Semple MacPherson Temple. He was found one bright sunny morning with his pants off:—Dead, behind the counter.)

“Mr. Kirsch,” Mr. D. Durst said, “I was once young like you. Today I have no energy. You’ll see as you get older. I was an inventor then. It was the late twenties. Just twenty-five years ago. It does not matter what my invention was. The early thirties destroyed many good ideas.

“I always thought I’d get back to it because it was such a good idea, but I realize now I’ll never try again. I’m too old, too immobile. It’s such a shame. I spent over one hundred thousand dollars working out the details and the patents. I had all the best places to use it lined up, rented even. I was making money with it when Balboa Island became a ghost town overnight, after the market crashed in twenty-nine.”

“What was the invention?” my father asked.

“It was a waffle machine,” Mr. D. Durst said.

My father and Mr. I. Lugosi both laughed nervously.

“Don’t you laugh! Don’t you laugh at me!” Mr. D. Durst said.

Then after a long pause, “Don’t you know that people always laugh at inventors. Don’t you know how hard it is to work out the details of a new idea. This is not any kind of waffle. This was a hot conical cake waffle. This was the sequel to the cold curled sugar cone. I am the sole inventor of the world’s first warm cupcake cones, and you don’t realize how important that still is. No one does. And no one will. Unless it’s brought back and shown to them.”

There was a long pause now, the kind that probably precedes every great storm, great battle, great explosion. Mr. D. Durst seemed irritated, and disappointment washed away his smile. He looked around the room and away from the eyes of Mr. I. Lugosi and my father. He was searching for the salve, it seemed, to soothe his soul—a salve that nobody had . . .

Suddenly addressing my father he said, “How much money have you got?”

“Nothing,” my father laughed back nervously.

“NO, NO, how much cash do you have on you?”

“About sixty-five dollars,” my father said.

“Mr. Kirsch, in my garage just downstairs and around the back are over fifty double waffle irons, all my prototypes, and all the test equipment I used to almost succeed back in twenty-nine. Not counting my time, worth—well, maybe—one hundred ten thousand in cash. How much would you pay me for this opportunity?” Mr. D. Durst said, putting my father on the spot.

“I told you; I have nothing. I have a mortgage, two children, and a wife,” my father said uncomfortably and looked at Mr. I. Lugosi who smiled back.

“I already have two children, grown and ungrateful. I already have a wife. And I don’t need a mortgage with payments due, not now anyway, “ Mr. D. Durst said, lightening up and smiling. Then he looked over at Mr. I. Lugosi “Can you loan him some money?” he asked.

Mr. I. Lugosi suddenly became serious. “I suppose so. How much?” he said.

“Mr. Kirsch,” Mr. D. Durst said, “for seventy-five dollars, providing you’re paying in cash —that’s with a ten dollar loan from you, Mr. Lugosi—I’m going to count on you to be my protégé in making me whole. I want you to bring back the conical warm cupcake waffle to America.”

“At which point my father said sagaciously, “I don’t mean to sound ungrateful, Mr. Durst, but I’d like to know more details—my cut and the expenses and . . .”

“Shut up,” Mr. D. Durst said. “Don’t negotiate! Don’t negotiate with me or the deal’s off! Your cut is you own it.”

“Wow,” my father thought.

“Wow,” Mr. I. Lugosi thought, and smiled at how transformed with the opportunity my father was. He handed my father ten dollars and said, “Let’s return tomorrow, Eddy,” as that was my father’s name. “I’ve got two kids, a wife and a mortgage too.” They all laughed.

“Have we got a deal?” Mr. D. Durst asked. His eyes widened and he looked twenty years younger as he smiled and glowered in anticipation.

Then suddenly it was as if my father wasn’t there. He went someplace in his head and there was an awkward silence in the room. Then just as suddenly my father returned; only God knows what he was thinking. My father gave Mr. D. Durst his money and Mr. I. Lugosi’s ten dollar loan, seventy-five dollars in all.

“My wife has the keys to the garage. Any time this week will be fine. It’s been a pleasure.” Mr. D. Durst said, his pallor slightly redder, his voice more vigorous than before.

As Mr. I. Lugosi and my father walked down the outside steps, Mr. D. Durst’s wife closed the door behind them smiling. “What have you done to me?” my father said to Mr. I. Lugosi.

“You took the ten dollars, you gave him the money” Mr. I. Lugosi said. “You did the deal.”

“You want part of it?” my father said.

“My garage is already full with sweaters,” Mr. I. Lugosi said. “I’ll watch you get rich, that’s enough for me Eddy . . . I like you . . . We can still sell sweaters to farmers I hope?”

“Of course,” my father said. “I’d be crazy to go head to head with the cold cone people. The first flat-bottomed cup cone already came and went; hot or not. Flat bottomed cones? Flat bottomed cones, they’re in every supermarket!”

“That’s right,” Mr. I. Lugosi said. “Why did you do it? Why’d you do the deal?”

“Because I had to think quickly: ‘Who’d eat ice cream in Echo Park and downtown near the Central Market where I have my stores?’” my father said, getting into the car with Mr. I. Lugosi and slamming his door shut.

“Yes?” Mr. I. Lugosi said in suspense, after slamming his, too.

“Well, Mr. Durst could only come up with ice cream, and a middle class Marie Antoinette’s crepe. But the whole state is filled with poor Mexicans, who are much more interested in burritos and enchiladas and tacos!” my father said—almost sideswiping a bus filled with former concentration camp victims as well as grandmothers going home from shopping kosher.

“Yes?” Mr. I. Lugosi said. They were driving back up towards the Farmers’ Market. The May Company went by the window of my father’s green ‘56 Ford.

“Masa Harina!” my father said. “A hot Masa Harina burrito or taco shell! Only one with a bottom to catch the juice that always falls on your sweater!”

“What’s a Masa Harina?” Mr. I. Lugosi said, thinking my father was crazier than ever.

“Corn flour,” my father said, and suddenly they both stopped talking for the rest of the night.

It is possible but not likely that anyone will ever again invent an Iron Maiden for batter—especially one with a heater—and for sure never again with a metal penis-like cone that goes diving into the hot, tortured, puffing batter just before the other half of the Iron Maiden comes crashing closed, chasing and punishing the flailing frail creamed corn with it’s final waffling steel and a frightening loud metal clang—even in the back bedroom, three rooms away from the kitchen, you thought something had happened to whoever cooked there. Sometimes a bad dream could come from overhearing its mere operation—especially in the middle of the night (which was of course the only time my father had to perfect his conical tortilla cone).

Fortunately, none of my few friends would normally choose to visit at those wee hours—that’s when my father would surround himself with the bowls of batter and various jars of oil, to “fuck around” with the Iron Maiden, so to speak.

He also had the earliest and oldest thermocouple-on-a-stick I’ve ever seen. It was for measuring the temperature of the waffle iron’s “vagina,” so to speak. It must have been obscene to do so because not once in the months and months of clanking did he ever use this long stick with wires in front of either myself or my sister K.K.[3] In fact, I came to beg him to use it after a while, since the carnage of near misses would pile upon the kitchen table as a testament to his progress—charred; burnt and mangled brown-black tributes to his inability to move from amateur to professional. How can you market what you cannot make?

At the time I didn’t understand, I was only sixteen. Usually I wanted nothing to do with business as a boy. For my mother needing the money badly trained me—out of guilt, I guess now—to believe that whatever job I might get was totally worthless to the family and to her—that we were so well off, I needn’t bother to help, despite our bankruptcy and her becoming the only working mother on our block.

Six years before when I brought home cash from selling papers on street corners after school let out, she refused to accept it. Later when I turned it into gifts for her, she was ashamed! So by the time I was sixteen, I got the impression that the only way to please her, if it was not to sell ice cream at Gilmore Stadium—no, if you didn’t get robbed on the way home you got shunned by her—perhaps was to make waffles.

She always complained to my father about money. It seemed their whole life was about the need for money or the lack of it. I could hear them argue in their bedroom at night. It would come floating through the heater transom.

The easiest way out was to avoid business entirely, I came to believe. That, coupled with the ideals from being in high school, led me to believe that the intellectual life was my calling. (But I still wanted to stop the complaining and discomfort of their private discussions, even though I had decided to be a dramatist or a philosopher or a poet—but one with an “allowance” per day.)

But very soon then, although I thought I might be thinking about Pirandello, Ibsen or Kaufman and Hart, I couldn’t avoid thinking about hot Masa Harina waffles and the “perfect burrito.” I couldn’t separate my life from my father’s.

Perhaps more than the thermocouple it was the measuring cup? There was definitely a lack of scientific method. What would the Master Builder have done? August Strindberg spent years as an alchemist. Eugene O’Neal’s father was a great actor, maybe mine was a great pastry inventor?

Maybe Strindberg knew he’d never get the Nobel prize for literature but Stockholm was also the home of Berzelius. Perhaps it wasn’t too late to get it for chemistry, after all Berzelius’ house was right next door to the Nobel committee’s house.

In any case, I was getting very upset; either over the clanging that started to increase proportionately to the myriad charred wreckage or over my mother’s complaints about the Iron Maiden behind the breakfast nook door and the fact that she’d like to park the car in the garage where fifty or sixty more waffle irons took up almost all the space.

Still my father was stubborn and the louder my mother’s complaints the more fervently he would clang later that night almost answering back that way. The Maidens had been cleverly moved-in months before around the time of the deal, but in the middle of several days so that my mother who was an executive secretary then would not be home to see it.

The prototypes of wood. The middle “Beta” issues of bolted metal. And then the fortitude of the finished cast-metal fleet, all weighing more than forty pounds each, over thirty years old, complete with dusty crushed cup cake cone spatters and aging yellow silk electric cords. A testament to my father’s will and determination (he lugged them all by hand and stacked them). A testament to Mr. D. Durst (each one bore his name proudly in bright red letters on a riveted metal tag, now darkened with the dust and other stored residues of the last thirty years). It was a sight, a scene like no other. We had the makings of a fortune in the garage—somebody sure had spent a lot of money.

Yet it seemed the more desperate my father became the more prolific and complete were his failures. If he merely used a color wheel and a clock he might have learned something, but he didn’t even seem to take notes.

I believe his theory was that he would arrive at the right batter, temperature, and “best-clang-tune” soon enough, as long as he kept working, and then he’d be right there to reverse engineer “the great moment.” It would happen soon.

To make a short story shorter, my father did one night make it happen. He did reverse engineer it. He was able to repeat it many late nights at last and by the end of a long winter, he could reproduce the “perfect” corn cone. I’ll say it again: Somebody sure had spent a lot of time and money.

A month or two passed. It was spring, who knows what went on. I’m sure he sold some sweaters in March but I don’t know after that. Certainly the farmland auctions bustled with money from the winter harvest. (My mother says Mr. I. Lugosi swindled my father out of some money. Maybe so, but still not before they had a conversation; that had to have influenced my father’s sudden behavior also.) It was then with a certain street wise knowledge of his total resources—(he was still paying off the bankruptcy to the government and the medical bills to a Texas hospital in Big Springs, near an oil slick highway where he turned over one rainy night, five years earlier, and broke his back on his way to sell a new line of skirts and sweaters to replace his fine tailored suits to Neiman Marcus stores in Dallas)—that my father did something that was completely wise and totally foolish at the same time. He arranged to demonstrate his new taco to the Carnation Company, at the time the largest miller and distributor of Masa Harina in the United States.

And so my story in a way ends here, and history takes over:

It was mid-June, the seventh to be exact. My father put on his best clothes. (I think there was only one cigarette burn, maybe not even a pulled button.)

The night before he had carefully made his best batter, poured it into two containers. It was the liquor of a whole winter’s worth of effort, the byproduct of many strains of hope, the elixir from which dreams are made.

To this and into a new red metal tool chest, he added a kit of miscellaneous support items: A screwdriver; a hammer; an electric soldering iron; pliers; the old thermocouple with its fraying wires and an ancient gauge for it that I had never seen before. He even had a measuring cup and a set of dry measuring spoons along with a brush for the peanut oil;—and of course he had a whole plastic container of this oil as well, for that was at last the oil of choice.

Everything was so well presented. He wanted to make sure there were no glitches. He had rehearsed his speech; he had washed and polished all of his appliances; and even taped all of the plastic containers so they couldn’t spill if they fell over in transit.

He left before my sister got up that morning. She commented that Dad must have a new girlfriend because he had left both the scent and the bottle of Russian Leather sitting out in the bathroom.

He also left the bag from Ohrbach’s—a store no longer in Los Angeles but popular then for its bargains—from the men’s shop, along with two price tags, one for a shirt, the other for a tie.

When my sister, K. K., and I sat down to breakfast and saw that the door to the room was comfortably flat against the wall, we both knew what was happening: The Iron Maiden was on its way to either glory or hell at Carnation Company, and our Dad was either a fool or a hero soon. Besides that we could finally move around better at breakfast and I knew, although Mom wouldn’t be totally happy, (she too was already gone that morning on her way to work) she’d be at least one better bitterness less distraught and that was in my mind half my proximate burden. The other half was heavier—the fleet of Iron Maidens awaiting their fate in the garage—they surely weighed tons together.

When Moss Hart came home with his first Broadway check he immediately moved his mother uptown to a nicer apartment. We all waited that evening for my father to arrive; my mother included. Would we be singing “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow”?

It was still light when we heard the familiar sound of his rattling front bumper approaching, and he eased his way into the driveway. He paused for a moment, and then opened his door carrying the red tool chest. His short collar was undone, his tie hung loosely.

Did Pasteur look like this when he thought up vaccination? Was “waffle money” the vaccine of this new generation, a century later? Did my father really invent the “drip-less taco?” the “perfect burrito?” His new shirt had drops of something staining the front as he approached the house.

My mother yelled out from the window as he came toward the front door. “Well?” she said, unable to contain herself.

“Well what?” my father laughed back and then he came through the front door.

“Are we going to get the garage back?” she said, almost jealous of the Iron Maidens sitting there.

“What happened?” my sister said with a smile.

“What happened?” my father said. “Isn’t anyone going to kiss me ‘Hello’?” he said as he put the toolbox on the floor behind the breakfast room door. My mom did. I’m sure we did. We all kissed and hugged him.

“What did S. N. Behrman do?” I thought, “or Pirandello for ‘Liola’? Maybe he took them all out for Chinese food?”

The Carnation Company was clearly not a farm operation. The building was as tall as the May Company, taller than Gilmore Stadium, maybe even as tall as Carthay Circle. Hadly Stuart (the founder, I think) probably built it with his own money even, and it was not architecturally mediocre. It was a thin high rectangle that looked like a slice of ice cream, pure white . . . and it stuck up just as prominently as any building in the North or South Jewish districts—only it was outside the ghetto—one might say it was remote—dairies are like that—but this building had mostly accountants, lawyers and marketing people in it. It was for Organization Men. It wasn’t just out there, it was really OUT THERE!

The Stuart family, I later learned, ran the business very close at hand. Mr. Hadly Stuart himself no less met with my father that day.[4] Hadly Stuart was not the kind of farmer my father was used to—(my father sold his “town clothes” to poor people—often he gave them to them when they had no money [Please, don’t tell his brother who was his partner!]).

(Did my father really walk exactly like Charlie Chaplin? Yes, he did. [But only when he wanted to, for as a child, in Coney Island, he sold Chaplin hats and canes when he was ten, in 1912.[5]])

In the summer the earth’s axis changes, and so this June seventh the sun cast in partnership with the Carnation Company building a particularly dark morning shadow across the parking lot as my father got out of his car with the red toolbox and lugged the Iron Maiden toward the elevator.

“It was all Mr. I. Lugosi’s idea,” he thought.

I really wouldn’t be here now if Mr. I. Lugosi hadn’t said back in March, “Eddy, you’re not going to be able to spend five or ten years doing this are you?”

“No,” my father said reluctantly.

“You don’t have the thirty to fifty thousand dollars you need to really market it correctly? Or do you?”

“We should stick to the sweaters,” Mr. I. Lugosi said.

Just a few months later, then, he swindled my father out of whatever little surplus capital he had. Was he trying to stop progress? Destroy the inevitable success of the “perfect” taco? Perhaps, being European, he’d never heard of Thomas Edison, or Horetio Alger, or Preston Sturgis.

My father must have felt terrible, to have trusted Mr. I. Lugosi, to be so stupid, so late in life. And so now as he sat, Iron Maiden in hand, in the outer office of Hadly Stuart, waiting, he must have still carried the gray pallor of the parking lot in with him: The dark side of being a failure, so late in life—Topped off I’m sure with a stabbing back pain for the effort.

Mr. Stuart, dressed impeccably—like a modern Englishman with a fine tailor—probably smiled at Dad and tried to relieve his discomfort when they first encountered. But he was hardly a chiropractor. Neither was he a shrink or a cheerleader.

My father’s nerves were scraped further when he was led inside the meeting room and saw that there was no kitchen table and that he would have to have the demonstration on the polished white birch wood of the company conference table. I’m sure it was the longest, widest lab table my father had ever seen—it may have been the longest, widest table . . .

But “Castro in trouble” or “Castro talks with Russia” or some other “Fidel-Cuba” random headline from the L. A. Times front pages had been already prepared by my father to shelter and shield any batter from splattering in just such a circumstance. So out of the red tool kit it must have come—cigar in mouth with dungarees and all—and been laid neatly on the table in front of Mr. Stuart and his gray suited colleagues. I sure hope my father hung on to the clanky Maiden somehow because it always left peanut oil residues on the floor behind the door in the breakfast room — the newspaper would be good for this too.

He had to have the Maiden in a box, or his suit and shirt would be splattered too. He wouldn’t have just grabbed it now?

Anyway if he did hold onto the heavy waffle iron his bad back already the worse for the trip from the parking lot and up the elevator, and from holding the iron body in the waiting room too, must certainly have caused him to sweat by the time he rested it on all of the papers.

He should have had a Sancho Panza, or at the least, myself, or a lowly employee of Carnation to assist. He should have been a WASP. He should have been a lot of things, however at the moment he was really on the spot to show off the corn cone.

The tool chest flew back open perfectly. But where was the long extension cord? No matter. One of the executives went to get a long cord, meanwhile my father pulled out his plastic containers and carefully unwrapped them.

In the nervous moments they waited, he must have been asked questions.

“Where are you from Eddy?”

“New York City,” he said.

“How did you get into this?”

“It was a favor to a dying old man.”

“A Mexican?” they must have asked.

The extension cord arrived, and my father plugged in his electric Iron Maiden’s yellow silk-corded plug. It had a chrome-covered switch midway (cat size to the mousy little ones we have today). He turned it on. How relieved he must have been to turn one moment from their staring eyes, their smirking but polite inquiry silenced only by their own awe at what was occurring. (The Iron Maiden was almost of a Russian Constructionist Design and sort of a contraption.)

My father began his pitch: “Gentlemen, The “Durst Waffle Iron” is warming. You’re probably wondering about the invention just now and the inventor. You see, Mr. Durst was a count in the last century, who—down on his luck after World War I changed the map of Europe forever and eliminated his homeland—arrived; first in Argentina, penniless; and then, one day, a year or two later, in New York City with enough money to stay at the Plaza Hotel.

“It was on the morning of the third day in New York that he discovered the coffee shop on the far side of the hotel made waffles, and that they had a very weak character.” My father then measured the temperature of the waffle iron’s cavity with the old thermocouple and read the dangling gauge.

It must not have been ready so he continued his story as they probably looked on—amazed at his technology.

“Now, the first question that comes to mind is probably just how did Mr. Durst accumulate enough money to stay for three nights at the Plaza?” my father continued, as they all smiled and started to like him.

“Gentlemen and Mr. Stuart!: He made all his money with a small troubadour drawing he found in a joke shop in London outside the British Museum, on his way to Buenos Aires—a bar trick he carried in his wallet—but first we measure the temperature again. Yes, it’s hot enough now. But don’t expect the first cone to be perfect. Is the first waffle ever? the first flap jack? the first flannel cake? the first anything? So expect the worst.” my father said brushing up the organs of the Maiden with his pastry brush, carefully watching that the peanut oil wasn’t too thick. To make sure, he wiped the iron with a clean towel.

“What was the trick?” Hadly Stuart said smiling.

My father was pouring the batter from one of his plastic bowls to just the right level slowly, slowly . . . Suddenly, my father put the batter down, and then “Clang” he forced the metal penis hard into the cavity of the Iron Maiden. A few pieces of batter splattered on an executive or two. Like soldiers on parade their pocket handkerchiefs came out to wipe it off.

Then, “Clang!” my father closed the top and was waiting, praying perhaps, as more batter splattered on him and Hadly Stuart.

“The joke?” he said, “I only saw it once. He never let me have it for more than a minute.” He wiped off the batter with a towel and then handed it to Hadly, nodding him down to his own dilemma.

“Sizzle,” the Iron Lady was flowing over—a little too full. Some of the batter dripped onto the newspaper. No one noticed.

“Can you draw it?” another executive asked.

“Not exactly,” my father said. “But it was a fold over illusion. There were some clowns, and a mule, and you had to get the clowns to ride the mule, or you lost your money to Mr. Durst.”

“Keklang!” My father opened the iron, and there looking like a “boner” standing in the air was a “perfect taco”—one made with Carnation Masa Harina.

“There!” my father said. And they all clapped as he filled it with some beans from another plastic container and got a little on his shirt.

“The point is,” my father continued, “that what you see is not always so important. It’s what you don’t see that intrigues most people. And that, when you’re drunk, never accept a dark stranger’s dare to make a decision about reality and illusion! It’s just too great a human burden to bear. . .”

My father didn’t care that he had batter on his coat, that his pants and shirt had caught a few drops of the peanut oil—he had been brilliant; and everyone in the room knew it, but only he knew that he had written it all the night before, and if there was any truth in it, I doubt it, save in heaven.

“What happens now?” my mother said.

“Well, they want me to try it out a few places first,” my father said.

“Mr. Stuart said he’d get back to me soon.”

Where was Moss Hart’s mother? She was still in her apartment near Christie and Delancy where maybe the heater didn’t work eighteen days a year, so the landlord could save five percent on heating oil, I thought.

I thought right because nothing happened for lots of months, maybe a whole year. There were telephone calls of course, and plans and greater plans, and even then the grandest plans. My dad now referred to Mr. Stuart as Hadly.

But most of the time, we bumped into each other trying to get around the breakfast room door—which stood slightly ajar again because the Iron Maiden was once more behind it sleeping in her “room.”

I started college and moved into my own apartment.

Once when I visited I asked my dad if I could sell a couple of irons from the garage to some buddies for ten dollars a piece. They liked the idea of a “penis waffle.” Reluctantly he agreed. He shouldn’t have because it left him wide open for my mother to suggest he sell them all. (She was at her wit’s end now, or as she liked to put it, “one step removed from a straight jacket,” to get the garage back.)

However, after a couple more months, reluctantly, my father called a junkman he found in the yellow pages.

“I’ve got some appliances,” he said. “They’re worth over one hundred thousand dollars, and I’d like you to appraise them for me.”

“I’m not an auction house or a pawn shop. Nor am I a museum curator or a saint!” the junkman said.

“Can you give a fair price? They’re made of steel mostly,” my father said.

“I can do that,” the junkman said. Then they arranged a time.

The junkman came around four o’clock. I wasn’t home nor were my father and mother. Only my sister K.K. was there to greet him.

He wore dirty blue overalls and had a pair of thick leather work gloves stuffed in one side pocket of the pants. He drove a black five-ton GM van. He seemed impatient. He was balding and looked like a fat Sid Caesar. He had a mole on his face.

“Where are the appliances?” he said.

My sister pointed to the garage, and led him to the door. He grabbed the metal handle of the door and threw it up. There, like an army, were the Iron Ladies, dusty and dirty and old; the aging legionaries of a war that never got fought.

“Ha!” he said, and he scratched his head. “Ha!” he said again.

“Once before I’ve seen this or something like it.”

“Yes?“ my sister said, anxiously wondering what “Ha!” meant.

“I’m going to offer you exactly what I offered that little old man near Fairfax, near the Carthay Circle . . .“Fifty dollars—take it or leave it. I can take them now, but if you want, I’ll pick it up on Monday?”

[1]A BRIEF HISTORY OF DEPARTURE

We were the leftovers of some broken Viennese dreams—at least my father said so. He also said my grandfather was the son of a tanner whose father (my great-grandfather) became very successful in the late 1880’s and was the probable Mayor of the town of Lemberg, sometimes in Poland or Russia or sometimes in Austria-Hungary. Martin Buber was born there. Around this time, my grandfather, the Mayor’s son, departed for New York City. The only other distinction for Lemberg was that it had unadorned beauty and was high in the mountains; therefore cool in the summer; therefore all the Hapsburgs, rulers of Austria-Hungary, vacationed there in the summers.

[2]Everyone knows there was a Senior Pico, but unless you were a historian, the only clear perspective was seen through a pair of Hollywood glasses back then. For me, it was all very close to Henry Roder’s little storefront shop of wholesale novelties, right across from the tombstone cutter’s, not too far from the best Kosher butcher’s and up the street from a good deli, “The Bagel”—very close to the Carthay Circle, another theater (now gone)—built by Mr. C. B. DeMille for his premieres, I’ve heard.

[3]My sister K.K. was mesmerized. She “truly believed” in our father. She somehow had the patience sit, to wait and to watch the burnt out toasted failures (three or four minutes for each) as if they were the valiant sacrificial soldiers of some historic campaigns. She was so sure. She was so innocent. She was so hopeful.

[4]Mr. Stuart’s children got very little I’ve heard when he died. Just the older brother (ala primogeniture traditions—long hated by Tom Paine) became wealthy.

[5]Years later, when we found out he was maybe four years older than he said and really born in 1898, that story was reversed to be 1908-1910; and instead of being ten years older than my mom he was fourteen or fifteen years older—what’s five years more anyway?

© 2014 Stanton Kaye.

Stan Kaye won a major award for his first film GEORG in Manheim, Germany from the UN when he was 20 in 1963. The panel of judges included Frederich Durrenmatt, Gunter Grass, Eugene Ionesco, Roberto Rosselini, George’s Auric, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Richard Leacock, Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch. The event was a celebration of New Ways and Means of Communication. In that tradition, this is a work of ficition.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.