Notes From the Underground of Lionel Menhuin Rolfe by Novelist Umberto Tosi

[Novelist Umberto Tosi was contributing writer to Forbes, covering the Silicon Valley 1995-2004. Prior to that, he was an editor and staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and its Sunday magazine. He was also the editor of San Francisco Magazine. He published one of his novels, Our Own Kind, serially at Boryanabooks.com. They became friends while working at the Los Angeles Times in the early 1970s.]

* * *

by Umberto Tosi

Here we are again, down to the last page of another year’s calendar. Time to celebrate the holidays – and think about what I’ve done, if anything, to make my 2018 worthwhile.

I know. It’s been a long while since we relied on actual calendars – although I love them. Like maps, they’ve been swallowed up by our smartphones. But whether marked on 4-color glossy paper or digital screens, it’s still a long way from May to December, as the Noel Coward song goes.

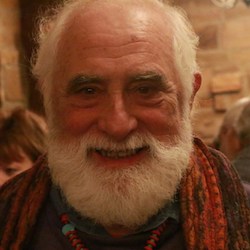

The chill rainy dawning of this December strikes me as particularly poignant given the recent death of a long-time friend and esteemed colleague, Lionel Menuhin Rolfe, He passed away on November 6 in a Glendale, California medical facility, at age 76, of a heart attack after many months of complications from diabetes, a stroke and painful infections following a fall.

Lionel was prolific author, essayist, raconteur, outspoken leftist, cultural commentator, Jewish contrarian and historian, media gadfly and chronicler of all things California, especially sprawling anomalies and the creative life of Los Angeles. And what else? So many things, but mainly and always one thing – a writer: Actually, he was a writers’ writer.

Like myself, he was born to a musical family (though his was world famous, unlike mine.) We shared a passion for classical music as well as literature, history and politics. He had musical training, but never performed. Too much competition in the family, he noted. He was the son of concert pianist, painter and poet Yaltah Menuhin, who with her sister Hephzibah – a noted concert pianist as well as antiwar activist – their older brother – the iconic violinist Yehudi Menuhin – made up the triumvirate of legendary child prodigies who became wonders of the world with their dazzling early performances, broadcasts and recordings.

I met Lionel in 1968 when I was associate editor for the Los Angeles Times’ Sunday magazine, then called, West Magazine. The slick, rotogravure-printed, color Sunday supplement had become a leading-edge design showcase and a mecca for established and emerging literary journalists as well as featuring works of avant guard visual artists. It rivalled New York Magazine at the time, and it was a tough sell for a young unknown like Lionel. I was 30, he was 26, and now I realize that we were barely more than kids, though we didn’t think so for a minute.

A 1970 West Magazine cover, featuring a story by feminist writer Mary Reinholz

Lionel walked in to pitch a story on his childhood as a progeny of the Menuhins, a shy, precocious L.A. kid, growing up amid larger-than-life performers, with family dissonances and cameo appearances by artistic luminaries and Hollywood celebrities. Even in his early twenties, Lionel resembled a lumbering, gentle bear in search of honey – which to him, was always a good story. He was a listener, who only spoke when he had something to say that was relevant to the conversation. People told him anything, comfortable spilling their secrets to this disarmingly draped, Venice Beach leftist coffee house denizen.

Unlike many of our 60s contemporaries, he was odd, not really cool, bohemian, not a hipster. Somewhat like myself, he was a pre-baby-boomer, and never quite fit either with flower children or establishmentarians. He was political and had written screeds and investigative pieces for local, underground newspapers, including the then-radical Los Angeles Free Press. He was divorced and, like me at the time, had two children. He drove an oddball, rarely seen car – not, not exactly cool, not yet considered a classic – a second-hand Citroen DS-21 – the kind you see in spy movies. In his later years, he had Oliver, an African gray parrot who sat constantly on his shoulder when he wrote at home. (Sadly, Oliver, old himself, died a few years ago.)

I recommended the Menuhin story to West’s editor, the late, jovial, sharp-eyed Marshall Lumsden, but he turned it down. Marshall, however, did need someone to write an outdoorsy feature scheduled for an upcoming issue. Oddly, the theme was to be spelunking. A hardy, cave exploration club had already been lined up to take an intrepid West Magazine reporter down into a labyrinth of limestone somewhere out in the Mojave Desert. Marshall had been eyeing me for the assignment and, white-knuckled, I had already made a list of excuses. Claustrophobic? Hell, I even hate to ride elevators! It seemed just as unlikely an assignment for Lionel, but, eager for a byline in the magnum mainstream L.A. Times, with its 1.5 million Sunday circulation, he accepted the assignment. Sure enough, a few weeks later he turned in a sterling, first person story that we ran with a major photo spread.

Looking back, spelunking turned out to be as apt a subject as any for Lionel’s Times debut. In the many years of writing for papers and magazines far and wide that followed, he never failed to dive deep below the surface of every subject he has touched upon – be it in culture, politics, the arts, media or the political and social history of California, a topic to which he returned often. Lionel was the most candid and personal of writers. He wrote lucidly, relating his subjects to direct experiences. That gave his stories and essays immediacy and depth. Most strikingly, Lionel never hesitated to kick away conventions and popular wisdom in his explorations.

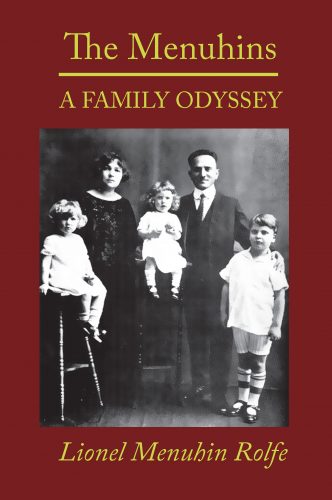

I would have liked to have seen the Menuhin story in West as well, but I did encourage Lionel to do much more with it at the time, namely to write a book.

He did indeed go on to write that family history and more. His book, The Menuhins: A Family Odyssey (1978) turned out to be a rich, semi-autobiographical, assiduously researched history of his family which he traced back centuries to the rise of mystical Hasidim in Russia, and its eventually migration to the United States. Lionel kindly mentioned me in the acknowledgements of his Menuhin opus, saying: “Umberto (Nino) Tosi, a fine editor and writer, was the person who long ago suggested to me that this was my inevitable first book.”

Through the years, I continued to admire the candor, wit, passion and perceptiveness of Lionel’s writing. Sometimes I envied his productivity, although he often viewed himself as far from success. He had basic melancholy that he expressed with self-deprecating humor and Jewish tsuris. He spoke his truth on paper, directly, with no literary or journalistic pretense. His wrote in a clear voice and unadorned style, free of self-promoting artifact. He kept eyes front, focused on the work, yet with self-deprecating charm and unsparing honesty about himself and others.

He authored numerous other books in the decades that followed the Menuhin history. They tell stories of famous and infamous people, muse about history, culture, Hollywood lore, California and world politics. These include Last Train North (1987), and Fat Man on the Left: Four Decades in the Underground (1998) the title being a dig at the rotund, notorious right-wing radio rabble rouser, Rush Limbaugh. Lionel’s other books include: Death and Redemption in London and L.A. (2003), The Uncommon Friendship of Yaltah Menuhin and Willa Cather (2009) about his mother. His self-satiric Misadventures of Ari Mendelsohn (2012), Lionel’s only published novel, The Fat Man Returns: The Elusive Hunt for California Bohemia and Other Matters (2017) his last book. He is probably best known for his guide, Literary L.A., a thrice-revised and updated collection of stories about Los-Angeles-connected authors and poets (1981 to 2002).

He was “an authentic storyteller,” says his friend, Linda LaRoche, who also characterized the thrice-divorced writer as a romantic. “Lionel was always deeply honest,” she noted in delivering a eulogy at his memorial service. “Part of the pull he had with women was his ability to be vulnerable. … It was Lionel’s way to prioritize the women in his life, making them his muse, when the talent he had was within him. This was the child in him that was dear, kind-hearted and generous…”

In the introduction to his 1998 book of ironic, autobiographical essays, Fat Man on the Left: Four Decades in the Underground, Lionel wrote: “My religion is the process of writing. Writing is my way of communing with God, with Nature, whatever you want to call it. I am an atheist, so I don’t have to seek for the exact words as those who believe. For me. God, Nature, these are at best, literary metaphors for whatever framework makes the most sense of things. I am in awe of the Universe. I worry about my own species. I love a lot of the people and things around me, so I do not want to lose the gift of life. But I will one day, as will we all, and that’s why I’ve written this book.”

I can go with that.

—————————–

Umberto Tosi is the author of My Dog’s Name, Ophelia Rising, Milagro on 34th Street and Our Own Kind. His short stories have been published in Catamaran Literary Reader and Chicago Quarterly Review where he is a contributing editor. He was contributing writer to Forbes, covering the Silicon Valley 1995-2004. Prior to that, he was an editor and staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and its Sunday magazine. He was also the editor of San Francisco Magazine and other regionals He has written more than 300 articles for newspapers and magazines, online and in print. He joined Authors Electric in May 2015 and has contributed to several of its anthologies, including Another Flash in the Pen and One More Flash in the Pen. He has four grown children – Alicia Sammons, Kara Towe, Cristina Sheppard and Zoë Tosi – and resides in Chicago. (He can be reached at Umberto3000@gmail.com)

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.