MY CHARMED LIFE AS LITERARY VALET

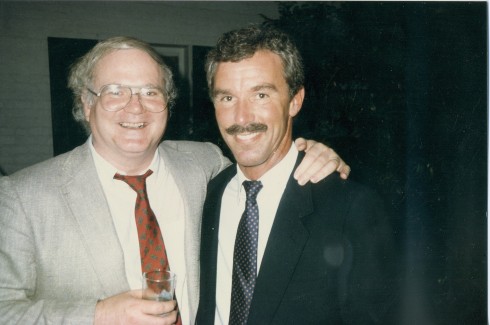

Pat Conroy (L) and myself at the kick-off of the publication of his 1986 novel, "Prince of Tides" in New Orleans

By Bob Vickrey

I must confess that I discreetly borrowed the expression “literary valet” from the memoir of distinguished former Random House editor, Jason Epstein. Although my career hardly paralleled his, I liked his analogy of our two distinctly diverse job descriptions.

I spent most of my working life as a field representative for an East Coast publishing house, which incorporated the duties of sales, marketing, and promotion of books for my company—a decidedly dry and ordinary business definition of a job. It wasn’t that way at all.

“Literary valet” may be a fancy way of describing what I did for a living. Publisher’s reps traditionally have done the ‘heavy lifting’ for their company’s writers behind the scenes by working with booksellers and are responsible for the placement of authors’ books into the marketplace. (That’s why I liked the ‘valet’ part.)

Publisher’s reps, independent booksellers, and most authors have been guilty of having avoided the basic rules and principles taught in “Business 101.” That consortium has fled the stayed life of those in the workplace who wore the pinstripe suits. We succeeded, although there were a few corporate trappings along the way.

Publisher’s rep as mentor…

When I began my career in the early 1970s, I was introduced to our Atlanta-based rep Norman Berg, who had developed a legendary reputation in the South—for very good reason. The man had been an instrumental figure in the publication of “Gone With the Wind” in 1936—not a bad legacy for a guy whose job description was “book salesman.” He was also a pivotal mentor in the careers of writers of contrasting decades and styles such as Margaret Kinnan Rawlings and Pat Conroy.

Berg had been a family friend of the Mitchell’s and had received a bulking manuscript written by his friend “Peggy.” He carried it along on a camping trip with several friends and finished reading the ‘rice-paper’ pages by flashlight in his tent in the early morning hours. Norman was so excited that he aroused his fellow campers from their sleep to proclaim he had just read a masterful work.

Several documentary films and books have been done of Mitchell’s life story and how her famous novel had found its publishing home at Macmillan, but few mention Berg’s name as an important link in the process of its publication. He was considered as having played a pivotal role in guiding the book from manuscript to print. He was given much credit for helping nurture the book as it made its way through the whole publishing process.

At the 1939 world premiere of the movie in Atlanta, Norman was a guest of Ms. Mitchell and her husband John Marsh, as they walked the red carpet through the crowds gathered outside the theater.

Berg also mentored Rawlings, who had written the classic novel “The Yearling.” In later years, he admitted his regret about being such a tough taskmaster that she may have lost confidence in her writing. He also confessed that Marjorie had been “the one true love of his life,” and that her work had suffered terribly under his unremitting pressure. He was certain that she might have been capable of adding other work to her impressive legacy if he hadn’t pushed her so hard.

Pat Conroy can testify to the “tough-love” approach Norman exhibited in his coaching of writers. Berg took him under his wing and moved him into his guesthouse on his 15-acre family farm in Atlanta he called Sellanraa.

Norman subsequently taught him the discipline the young writer had so desperately needed to become a successful writer. Conroy had recently written and published his second book “The Water is Wide” about his first year teaching experiences on Daufuskie Island, off the South Carolina coast. He had just begun work on his first novel, “The Great Santini,” and Berg’s guesthouse gave him the proper setting and privacy to finish his book.

Conroy still gives Berg credit for being the greatest guiding force in his success in becoming a writer of substance. However, Norman’s toughness was so intense that Pat could rarely feel truly satisfied with his finished work. Berg always let him know that it could have been better.

Yet another of our company field reps lived next door to John Cheever in Ossining, New York. Yes—that John Cheever. I remember sarcastically asking him if Norman Mailer lived on the other side of him. He casually mentioned that Cheever occasionally had “bounced story ideas off him from time to time.”

Changing roles for changing times…

The rep’s role in the field of acquisition was already beginning to wane by the time I joined Houghton Mifflin. So, when asked the age-old question, “What did you do in the war Daddy?” I’d love to have been able to say that I was responsible for discovering Alex Haley and putting his landmark book “Roots” on the literary map. Neither Phillip Roth nor John Updike ever bought me dinner and picked my brain for story ideas. So much for legacy.

Publisher’s reps began to take on greater responsibilities in the marketing and promotion of authors’ books. We spent an inordinate amount of time as “literary escorts” on their promotional tours in our territories. We shuffled writers around town during their media and bookstore appearances. Most of us were treated alternately as taxi drivers or princes of the city, fully depending on the author’s mood and/or ego.

While most writers who were promoting their new book had been told that their publisher’s representative should be considered a major ally, a few of them never got the message. Many new authors never fully realized that we were responsible for setting up their book signings and could help them enormously with the merchandising and ultimate success of their book.

I met best-selling writer Irving Wallace shortly after I had moved to Los Angeles. I happened to bump into him and his wife Sylvia browsing Brentano’s Bookstore in Beverly Hills on a Saturday night. I worked up my courage and finally introduced myself as simply “the local Houghton Mifflin guy.” That was all Mr. Wallace needed to hear. He called Sylvia from the front of the store and gave me an incredibly warm introduction as one who had just recently joined the Southern California book community.

I could only imagine how welcoming he must have been to his own Simon & Schuster company representative. We talked for half an hour, and they invited me to a book party at their Brentwood home the following Saturday night. He was already one of the most popular and successful writers in America, and I began to understand that his kindness and diplomacy may have gone hand-in-hand with his talent in producing a long successful string of best-selling books.

Literary tomes versus celebrity dish…

After I got tagged as the “Hollywood rep” by my peers back in Boston headquarters, I thought the moniker was tinged with slightly more than humor, and was firmly grounded in attitudes about Southern Californian’s less-than-serious reading habits. Just as I was about to build my case to defend my home turf, the sky opened up and the market was suddenly flooded with celebrity biographies.

That’s probably how I seemed to have ended up sitting in the “green rooms” of television studios with fading movie stars who had written their life stories—rather than enjoying a closer association with the country’s greatest writers, as my friend Norman Berg had experienced decades earlier.

David Niven had written a delightful book called “The Moon’s a Balloon” in 1972, and its success sent agents and publishers scurrying theHollywood back-lots to find the next #1 New York Times best-seller. While Niven set the standard of excellence early in the game, the quality of many biographies published afterward had become rather suspect, as stacks of unsold remainders began to fill tables at bookstores across the country.

Publishers had gone celebrity crazy and a frenzied American reading audience was lapping it all up. Best-seller lists were suddenly laden with biographies of Laurence Olivier, Katherine Hepburn, Henry Fonda, and Joseph Cotton.

However, the precedent had been set, and the mix of celebrity names became regular entries in publishers’ seasonal catalogs. Booksellers liked the occasional sales boost that many of these books had given their business, but quietly mourned the fact these tell-alls had replaced books of substance on best-seller lists.

No regrets about career choice…

Lest I leave the impression that I have felt cheated out of some literary “inheritance” of another time and place, I leave you with the assurance that I left my job with fond memories of having spent a contented working life with wonderfully creative minds responsible for writing and publishing the books of our times.

I had been given the distinct privilege to enjoy an association with authors as diverse as Pat Conroy, Robert Stone, Jerzy Kosinski, and Paul Theroux in my early years with the company.

In later years, we published young, talented writers like Carolyn Chute, Ethan Canin, and Mary Morris. We also became the recipient of the splendid later work of James Carroll, Howard Fast and Phillip Roth after they had published earlier books with other houses.

A talented young Indian-American woman was signed to a contract in the late 1990s by our editors for her unfinished novel, but in the interim; she offered her short story collection that would eventually become a Pulitzer Prize winner (“The Interpreter of Maladies.”) Jhumpa Lahiri’s talent was immediately lauded by critics and readers alike, and her meteoric ascension to literary stardom was an inspiration for many of us veterans who had become tired and cynical about believing that publishing miracles could still happen.

That model of talent and ultimate acclaim is what emboldens and sustains publishing dreams for both the writer and the publisher—and despite my occasional protestations the dream remains very much alive today.

Bob Vickrey is a freelance writer whose columns appear in several Southwestern daily newspapers including the Houston Chronicle and Ft.Worth Star-Telegram. He is a member of the Board of Contributors for the Waco Tribune-Herald. He lives in Pacific Palisades, Ca.