Leninism and Nazism: Opposites, Twins, or Siblings?

Leslie Evans

The Devil in History: Communism, Fascism, and Some Lessons of the Twentieth Century. Vladimir Tismaneanu. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. 320 pp.

Vladimir Tismaneanu is a Romanian who grew up under the Stalinist dictatorship that ruled his country from 1947 to 1989. Born in 1951, he was almost forty when Ceausescu was overthrown. His father was an important propagandist for the Communist government. Vladimir headed the 2006 Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, which condemned the Communist period as a criminal regime. The report was highly controversial, denounced by high ranking former communists who were condemned by name, by liberals who pointed to Tismaneanu’s past as a convinced Marxist-Leninist, and by the far right because Tismaneanu is a Jew. He teaches currently in the United States at the University of Maryland.

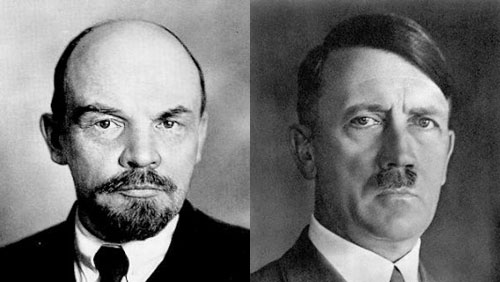

In The Devil in History Tismaneanu spends almost no time on the fascist devil. Where he does reference them it is in sociological generalities about Hitler Germany, where the crimes of the Nazis are so well known they require no elaboration. He deals with them mostly by occasional paragraphs in which he establishes specific similarities and differences from their leftist enemy.

In addition to his life experience, Tismaneanu is sitting on a mountain of historical and sociological studies of the Communist record, many drawing on the long-secret Soviet and East European archives, that opened only in the last twenty years. His style is marked by stating, in almost every paragraph, his conclusions in the form of quotations from the work of others in the field, to which he then appends his agreement or disagreement. He traces the Communist project from the Russian Revolution, which he regards as an antidemocratic coup, through its Leninist and Stalinist incarnations, its expansion into Eastern Europe, and its decline, the beginning of which he dates from 1956.

I want to narrow the juxtaposition of Tismaneanu’s title. On the political right, the word “fascism,” though commonly used in America to signify Hitler and his Nazis (a term never used by the Germans), covers a broader swath. Under Mussolini, who invented it, his government was far less repressive than either the German Nazis or the Soviet Union under Lenin, much less Stalin. In Italy there were no mass killings or concentration camps, at least until well into World War II when the Germans were calling the shots. So on the right it would be better to take the worst example directly: Hitler’s National Socialists.

On the left, few would dispute that Stalin’s Russia was as bad or nearly as bad as Hitler’s Germany. It murdered many millions more than the Nazis – by current estimates something between 20 and 35 million of its own citizens, though not matching the cold blooded industrial thoroughness of the Holocaust. China in its Maoist period shot and deliberately starved to death far more, with 45 million dead being a midrange estimate. Pol Pot killed a greater percentage of his country’s population than any of the others.

For me the most interesting question in Tismaneanu’s study is what to make of Lenin and the October Revolution. On the right, hardly anyone outside of small neo-Nazi sects looks back on Nazism as a noble experiment gone wrong, yet there are many who still take this view of Lenin and the early days of Soviet Communism. It is an article of faith of the various Trotskyist groups and the steadily diminishing number of self-identified Marxists. It was propounded by the leaders of every successive layer of efforts to reform the Communist parties from within, from Trotsky’s Left Opposition to Khrushchev’s 1956 de-Stalinization speech, to Gorbachev’s perestroika. And this idea of the good Lenin succeeded by the bad Stalin is surprisingly widespread among liberal historians. Before we can characterize Lenin-era Communism some of the romantic aura that still surrounds it needs to be dispelled.

Lenin’s Russia

Of course, most of the facts about Bolshevik repression were known at the time, and widely reported. But the seizure of state power by Marxists in a major European country was too great a victory for much of the left to disavow it. A large section of the socialist left hitched its wagon to the Communist revolution and stopped up its ears. We are all familiar with the Communist Party members in the West who for generations dismissed reports of the Soviet Gulag as an invention of capitalist enemies. Much of the would-be democratic left did the same, at one remove, conceding Stalin’s crimes but dismissing the reports of Bolshevik killings and concentration camps as exaggerated, as necessary elements of the Russian civil war, as somehow different in kind and degree from the horrors that followed, and in any case justified, while infinitely smaller evils by capitalist democracies are met with howls of outrage.

There is now a large post-Communist literature drawn from the Soviet archives that makes this view untenable. (I have touched on this issue before in my essay “Anticapitalism, the Hyperstate, and the Current Crisis“), also included in my book Shaggy Man’s Ramblings. Tismaneanu points in particular to Robert Gellately’s Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe, which provides a pithy summary, as good as any. Here are some of the facts.

Less than forty-eight hours after the seizure of power the Bolsheviks issued their decree on the press, closing many of the existing papers and journals other than their own and placing what remained under strict party censorship, while moving inexorably to destroy all of the media that was not directly under party control. They set up the Cheka, the secret police, and opened concentration camps, which were soon filled with leaders and members not only of the conservative parties but of the liberals, of the Social Revolutionaries who represented the country’s peasant majority, and of the other Marxist parties.

When, on January 5, 1918, the elected representatives of the Constituent Assembly gathered from across Russia, the results of the country’s first free elections, the Bolsheviks had won only 24 percent of the vote. An unarmed civilian demonstration of 50,000 in support of the democratically elected assembly was fired on by Bolshevik troops, killing about twenty people.

In June 1918 the death penalty, abolished by the February revolution, was restored. On August 9, 1918, Lenin ordered the Nizhni Novgorod soviet to “instantly commence mass terror, shoot and transport hundreds of prostitutes who get the soldiers drunk, ex-officers, and so forth.”

On August 11 in a telegram to Penza he ordered:

“1. Hang (hang without fail, so the people see) no fewer than one hundred known kulaks, rich men, bloodsuckers.

“2. Publish their names.

“3. Take from them all the grain.

“4. Designate hostages.”

Gellately comments here: “Seizing ‘all the grain’ meant that the relatives of those not killed might well starve to death, and that was the point in taking it.”

On September 3 in a party newspaper the deputy head of the Cheka, I. K. Peters, ordered “instant execution” of anyone found without identification papers. The Cheka in 1918 executed 500 hostages in Petrograd. The official start of the Red Terror began on September 5 with a Sovnarkom decree authorizing execution by the secret police without trial, as well as the official inauguration of the concentration camp system. Cheka head Felix Dzerzhinsky in a February 17, 1919, report coauthored by Stalin stated that inmates of concentration camps would be used as state labor, and that such incarceration would be extended from political prisoners to also include “gentlemen who live without any occupation” as well as those with an “unconscientious attitude toward work, for negligence, for lateness, etc.”

By September 1921 there were 117 camps with more than sixty thousand prisoners run by the NKVD and the regular justice system, with fifty thousand more in another hundred or so camps run by the Cheka. Gellately writes:

“During 1920 at the Kholmogory camp the Cheka adopted the practice of drowning prisoners in the nearby Dvina River. A ‘great number’ were bound hand and foot and, weighted down with stones around their necks, were thrown overboard from a barge.” He adds that there was a very high mortality rate in the Cheka camps and many massacres, “so estimations of the total number of prisoners may bear little relation to the reality. Isolated figures suggest that the scale of the killings was enormous. At certain points, prisons were emptied by shooting all the inmates.”

Basic citizenship rights were withdrawn from all those judged to be opponents of the new regime. This did not require any action on the part of those so excluded, not even verbal criticism of the government. Gellately writes:

“The stain of opposition was indelible. It might amount to no more than the accident of being born a member of the bourgeoisie – the son or daughter of a shopkeeper, for example – but the mark could never be erased.” Lenin called for putting “lazy workers” in prison and shooting “idlers.”

The Bolsheviks did not hesitate to shoot down striking workers, and execute leaders of the other left parties. But their greatest repression was directed against the Russian peasantry. This went under the rubric of a class war against the “kulaks.” Most Western communists and sympathizers of the Russian Revolution took this in stride, imagining a kulak to be something like a Latin American latifundista, deserving of everything they had coming to them. Gellately, on the basis of the long-secret archives, corrects this impression:

“Anyone could be labeled a kulak, from the person who lent neighbors money to one who kept a tidy garden.” He adds:

“In the heady days of late 1917 and early 1918, peasants had been enthusiastic about Bolshevism, which promised them land without payment and encouraged them to pillage the bourgeoisie and nobility. By mid-1918 much of that support had faded. Over the next two years there were thousands of riots and revolts as the peasants fought back. What most of them wanted, as they had for generations, was free title to their own land. All such attitudes, however, as well as protests, were now labeled ‘kulak rebellions’ and savagely repressed.”

A virtual army of urban toughs, some 30,000 to 40,000, were dispatched into the countryside to seize peasant grain for the cities. Often they took all they could find, leaving the peasants to starve. The government was pitiless toward the peasant families. Gellately again:

“Peasant were killed if suspected of holding back grain, and workers were shot if they protested. In the first two months of the terror some ten to fifteen thousand summary executions were carried out. . . . The Cheka killed and abused their victims without mercy. They robbed and plundered and in drunken orgies raped and killed their way through one village after the next. Completely innocent family men were arrested so that Cheka officers could take their wives as mistresses. Daughters were blackmailed into trying to save their families by offering themselves for the pleasures of some drunken official.

“Suspected enemies could expect cruel torture, flogging, maiming, or execution. Some were shot, others drowned, some frozen or buried alive, and still others were hacked to death by swords. Just who all these ‘enemies’ were depended on the whim of someone in the Cheka, the Red Guard, or the Red Army. The killers honed the practice of having those about to be executed dig their own graves.”

The Red Army executed between 50,000 and 150,000 civilians in the Crimea in 1920 after driving out the White army. On January 24, 1919, the renamed Communist Party’s Central Committee ordered the “total extermination” of the traditionally independent Cossacks. In 1920 in the North Caucasus and the Don area the Cheka executed more than six thousand people. Cheka leader Karl Lander reported that “for lack of a better idea” the Cheka in Kislovodsk killed all the patients in the local hospital. Gellately adds, “An integral part of these operations involved the wholesale sexual exploitation of the women.” On October 23, Serge Ordzhonikidze, later a prominent figure in Stalin’s government, ordered the destruction of the Cossacks as a people. Again Gellately:

“The most reliable estimates indicate that between 300,000 and 500,000 were killed or deported in 1919-20. These losses were suffered by a population totaling around three million at the time.”

Things were not much better for ordinary Russians under Bolshevik rule. Being declared a “class enemy” was not based on anything a person had done or even said. Gellately quotes Martyn Latsis, a Cheka leader:

“We are not waging war on individual persons. We are exterminating the bourgeoisie as a class. During the investigation, we do not look for evidence that the accused acted in deed or word against the Soviet power. The first questions you ought to put are: to what class does he belong? What is his origin? What is his education or profession? And it is these questions that ought to determine the fate of the accused.” Lenin made some exceptions for technical experts that the government needed to keep the military and the economy afloat. Many tsarist officers were retained, their families held as hostages and shot if the officer disobeyed, and some factory owners with special knowledge of productive technique survived.

The French Revolution at least limited the guillotine to the actual aristocracy. Lenin’s Bolsheviks unleashed their greatest savagery on the peasantry, the urban middle class, trade unionists, and the supporters of the liberal and leftist political parties. The February 1917 strike at the Putilov steel factory in Petrograd is credited with being the decisive event in compelling Nicholas II’s abdication and opening the February Revolution. When the Putilov workers struck again, in March 1919, raising solely the demands that the Bolsheviks themselves had championed the year before: All Power to the Soviets, for Soviet Democracy, etc., the Cheka on March 16, 1919, stormed the factory, arrested 900 workers and shot 200 without trial.

Tismaneanu quotes Bukharin’s 1920 Economics of the Transition Period, where the Communist Party’s chief theoretician maintained that “proletarian coercion in all of its forms, beginning with shooting and ending with labor conscription is . . . a method of creating communist mankind out of the human materials of the capitalist epoch.” And the Bolsheviks indeed tried to shoot their way to communism.

What was the total of this savagery? The most authoritative and extensive compilation of the statistics has been done by R. J. Rummel, who has coined the term “democide” to distinguish the mass murder of one’s own citizens and ethnic compatriots from genocide, the extermination of other peoples or ethnicities. In his Lethal Politics Rummel gives the following figures for civilian deaths by the Red Terror, solely for the period 1917-1922 under Lenin’s rule, not including casualties of the civil war:

“The number killed throughout Soviet territory by the Red Terror, the execution of prisoners, and revenge against former Whites or their supporters possibly involved the murder of between 250,000 and 3,650,000 people; most probably about 500,000, including at least 200,000 people officially executed. Among all the conflicting figures, 500,000 seems the most prudent estimate. Yet, as large as it is, it may be overly conservative (and this is what makes it prudent.)”

I could go on, but I think any reader with a sense of humanity will see that this was not a liberation but a descent into brutal state slavery in which any good intentions of Lenin and his followers were drowned in their own callous disregard for the most elementary human values.

Before turning back to Tismaneanu it is worth citing as a first comparison between Leninism and Nazism a point made by Robert Gellately. Lenin and Stalin, he states, did not seek approval for their actions from any segment of the Russian people. “Even in their own minds they derived their legitimacy and authority not from the people but from Marxism and the laws of history, of which they supposedly had superior knowledge.” Hitler, in contrast, was a populist. At every stage he sought, and won, the approval of the mass of the German people. His concept was an homogeneous Germanic populace, to achieve which required the expulsion or extermination of Jews, communists, homosexuals, Gypsies, non-Germans, and the physically unfit. But he repeatedly sought the approval of the “average” German. Gellately quotes Ian Kershaw’s conclusion that Hitler’s personal popularity and authority “formed the central vehicle for consolidating and integrating society in a massive consensus for the regime.” Hitler for the duration of his rule, killed very few German “Aryans,” other than those who died in battle in the war.

Tismaneanu’s Critique

Our author stipulates that communism and fascism each have their “irreducible attributes,” but share a long list of similarities, which leads him to characterize them both as incarnating “diabolically nihilistic principles of human subjugation and conditioning in the name of presumably pure and purifying goals.” He was particularly struck in his own experience by the readiness with which Romanian Communism after 1960 incorporated more and more characteristics of the fascist right, including ultranationalism, xenophobia, and antisemitism. This was not limited to Romania but was true as well of the postwar Soviet Union and Poland.

This “baroque synthesis” was possible because of the many shared traits of the pristine versions of these systems, first of all, that they are “ideological states,” where the government is the owner of absolute truth:

“Both movements pretended to purify humanity of agents of corruption, decadence, and dissolution and to restore a presumably lost unity of humanity (excluding, of course, those regarded as subhuman, social and racial enemies).”

Both movements arose through the victory of monolithic parties with a military component that were utterly hostile to “liberalism, democracy, and parliamentarianism.” Both denied any autonomy to the individual and claimed the right to impose the state’s views by force on virtually every issue, and to arrest or kill even the most modest dissenters. Both rested on revolutionary mobilizations of the masses in which personal liberty was expunged and replaced by a sense of belonging to a great historic renovation of society into new forms to which all personal freedom was surrendered.

While these currents had gestated in small groups in society’s wings, their opportunity to become national and international powers was opened by the disastrous mass slaughter of the First World War, which deeply shook people’s faith in the Western secular religion of onward and upward progress governed by the often corrupt give and take of electoral party politics.

In power, communism and fascism vastly expanded the power of the state over individual and collective life, aiming explicitly at the complete elimination of individual autonomy. All persons were at the disposal of the state. Disloyalty was met with a death sentence, even at the level of private speech or, still more inescapable, falling afoul of pseudoscientific criteria of one’s ethnic or class identity. Behind the state apparatus, power was held by the centralized party, whose rigid ideology dominated all public means of communication and education; a ubiquitous secret police apparatus spied on everyone; while the populace was thrown into the multifaceted and implacable machine that sought to remold them, as Tismaneanu put it, according to the recipe for the “cult of the ‘New Man.'” Those who didn’t meet the standards of the cookbook were disposed of. And, more than any of these, the two systems resembled each other in their “genocidal frenzy.” Both systems killed vast numbers according to impersonal generic criteria.

The forcible integration of the ideal types into the transformed nation went hand in hand with the exclusion and eradication of those who did meet the ideological criteria. Tismaneanu writes:

“Both Stalinism and Nazism emphasized the need for social integration and communal belonging through the exclusion of specific others.” They aimed to achieve “imagined projects of the perfect citizenry.”

Both systems employed constant, state manipulated, mass mobilization in campaigns intended to show progress toward an apocalyptic transformation that was to produce an earthly paradise. Both prized the new technologies of the twentieth century and employed them indiscriminately in industrial production and in mass murder. Naturally there were lots of people you didn’t expect to meet in paradise, and these states devoted vast energies to seeing that such enemies and misfits would no longer exist. As Tismaneanu puts it, “Communism, like Fascism, undoubtedly founded its alternative, illiberal modernity upon extermination.”

A cardinal difference in the two systems was that Nazism had no humanist pretensions. Its roots were in the Counter Enlightenment of blood and soil, organic nationalism that prized only its own ancestral line. It advocated German rule over all others on the basis of superior will and alleged biological superiority. The Communist current emerged from Marxism, the most extreme wing of the Enlightenment, which evolved a doctrine of ruthless global reengineering of all societies to conform to a single model of propertyless universal equality. Nineteenth century Marxism, and still more its totalitarian Leninist incarnation, looked to the state as the instrument to administer the post-revolutionary society in its every aspect, with all the homogenizing and exclusionism that this implied. Unlike Nazism, reform movements repeatedly arose within the Communist polis calling for somehow realizing the ever-lost humanist promises of Marx’s early writings. The conundrum of Marxism was that it propounded a goal of universal happiness while firmly advocating a system that explicitly destroyed civil society and was to replace it with a monolithic state apparatus that controlled every aspect of life: all jobs (as there was to be no private property), all means of mass communication, central control of the monetary system, combined with state suppression of disapproved beliefs and their advocates, beginning with religion and political liberalism.

This distinction between the two systems is real enough, but Tismaneanu perhaps gives it too much weight in explaining why Communism expanded after World War II while fascism did not make a comeback. Fascism, after all, was not a purely German institution. It can be adapted to any aggrieved national or ethnic group that rejects human and civil rights for its enemies. The postwar failure of fascism to rise from the grave has much to do with revulsion at the Holocaust, which the non-German fascist states had less responsibility for, and the fact that the fascist side lost the war.

To return to the common rejection of liberal democracy by our two opposed movements, Tismaneanu characterizes them both as revolutionary. Leninism he brands “a mutation” within social democracy that rejected its previous democratic legacy. The Marxists were wrong, however, to see the Nazis as a mere counterrevolution in defense of capitalism. In their own way the National Socialists strove to destroy the existing pluralistic society, “a rebellion against the very foundations of European modern civilization.” They led, he says, “an attempt to renovate the world by getting rid of the bourgeoisie, the gold, the money, the parliaments, the parties, and all the other ‘decadent,’ ‘Judeo-plutocratic’ elements.” The real stakes in the twentieth century were not in the defeat of fascism as such but in driving back the dual offensive against liberal democracy. He adds that while both fascism and communism were dealt heavy blows, that “new varieties of extreme utopian politics should not be automatically regarded as impossible.”

Both movements were charismatic, rejecting legal codes that were binding on the government. They differed in that fascism’s charisma was vested in the individual leader while communism’s was vested in the party, though this often placed few restrictions on the Communist leader’s authority. Tismaneanu laments that in the West the anti-fascist tradition remains strong while the history of Communism has been cloaked in “silence, partiality, or ignorance regarding the crimes and dictatorship of Leninist party-states.”

Here we come to another cardinal distinction between the two illiberal totalitarianisms. Tismaneanu quotes the late Tony Judt: “[T]here is a difference between regimes that exterminate people in the inhuman pursuit of an arbitrary objective and those whose objective is extermination itself.” Both regimes excluded millions of their own people from both citizenship and the right to remain alive. In the Nazi case the excluded were hunted down and murdered. In the Leninist case a great many were shot, others were interned in concentration camps where most died, still others, mainly among the peasantry, had all their food taken and starved to death, or, if they protested, were killed by the military. Here, the government preferred them dead, denied them any pathway to regain normal human rights, but some small percentage of the excluded nevertheless lived through it.

With that qualification, those deprived of citizenship in the USSR were essentially criminalized. At best they lost their jobs and the ration cards required to buy food, amounting to a slow death sentence unless others dared to help them. This exclusion from the means of existence was widely extended to whole families and related kin groups. Social types so excluded included Nepmen, traders, kulaks, persons of nationalities other than Russian, even if they had been Russian citizens, particularly Germans, Poles, Koreans, Greeks, and Chinese. “The disloyalty of the fathers was thought to be passed down to the sons. Both rightlessness and statelessness became inherited traits” (Tismaneanu is here quoting Golfo Alexopoulos). Soviet terror became the Russian version of the Final Solution. As Tismaneanu writes, of both systems:

“Millions of human lives were destroyed as a result of the conviction that the sorry state of mankind could be corrected if only the ideologically designated ‘vermin’ were eliminated. This ideological drive to purify humanity was rooted in the scientistic cult of technology and the firm belief that History (always capitalized) had endowed the revolutionary elites (of extreme left or extreme right) with the mission to get rid of the ‘superfluous populations.'”

In Germany the exterminationist repression was directed at minorities (Jews, gays, Roma, the disabled) and foreigners. That allowed Hitler to remain popular with average Germans. In Lenin and Stalin’s Soviet Union it was directed at the mainstream population, where one person in five went through the Gulag. In part because of its huge extent, more people survived the Gulag – there were few but still significant ways to live through or escape it – than did the German murder machine. But also because of the scale and the length of time during which it was in place, vastly more people died in the Soviet effort to cleanse its population of those that didn’t match its blueprint.

Tismaneanu raises a chilling question about these systems: what was going on in the minds of the people who constituted their mass base? “How was it possible for millions of individuals to enroll in revolutionary movements that aimed at the enslavement, exclusion, elimination, and finally extermination of whole categories of fellow human beings?” He explains it as surrender to “the ecstasy of solidarity, the desire to dissolve one’s autonomy into the mystical supra-individual entity of the party.” And elsewhere in his text:

“The cult of violence and the sacralization of the infallible party line created totally submissive subjects for whom any crime ordered by the upper echelons was justified in the name of ‘glowing tomorrows.'” A similar psychological process operates today for radical Islam’s suicide bombers, with the exception that their sacrifice is not with the expectation of hastening a distant earthly heaven but of themselves entering Paradise momentarily.

Americans, in this most individualistic of modern states, are prone to assume that, after food and shelter, the main thing people want is personal liberty. That is far from the truth. People have many motivations in their collective lives. Under the right circumstances they are equally likely to embrace regimentation, and slaughter of real and imagined enemies. This is the stuff of radical religious, nationalist, and strongly ideological secular movements throughout history, down to our own day in the current upwelling of radical Islam.

As Tismaneanu puts it for the Soviet case:

“Generations of Marxist intellectuals hastened to annihilate their dignity in this apocalyptical race for ultimate certitudes. The whole heritage of Western skeptical rationalism was easily dismissed in the name of the revealed light emanating from the Kremlin. The age of reason was thus to culminate in the frozen universe of quasi-rational terror.”

It is easier to explain why leftist radicals far away from the Soviet Union, who knew little or nothing about what actually took place there, and got what information they had from Marxist sources, became champions of the Russian Revolution. Over the years, as the monstrous evils of the system became undeniable, many retreated to a second line of defense: the heroic people’s tribune, Lenin, was betrayed by his acolyte Stalin. The Leninist past was by then long gone and few of these radicals cared to delve into the by now voluminous historical documentation of the early years of Soviet power. There are still some of these folk around today.

Tismaneanu goes on to trace the evolution of the Leninist structures – secret police, shooting without trial, concentration camps, abolition of civil society and its replacement by state control of individual lives, rewriting of history, extermination of whole groups based on purely sociological criteria – into the Stalin era. In particular, after the end of World War II, the Soviet government incorporated new elements pioneered by the Nazis, most importantly official antisemitism. The Soviet media for decades hid the fact of the Holocaust and began a purge of Jews from the party and from the professions. “Under Communism, the Jews became a target of policies of exclusion, isolation, and punishment on the basis of their ethnicity, were deemed potentially disloyal (‘enemies of the people’) and inherently bourgeois (‘class enemies’), Jewish identity turned at times under Communism into an innate, invariable, and even hereditary source of otherness that called for state-engineered excision.”

Stalin, like the Nazis, adopted a theory of innate and inescapable national character. The Russians were the heroic carriers of Communism while the inferior nationalities were, in Tismaneanu’s summary, “decadent species spoiled by a profit-seeing mentality.” Pravda in the early 1950s was filled with letters denouncing Jews as traitors and demanding that the lot of them be purged from the party and all high office. This while the embers at Auschwitz were still warm. Here Tismaneanu quotes the Polish philosopher and critic of Marxism Leszek Kolakowski on the state’s rationale in adopting antisemitism and purges directed at other non-Russian nationalities:

“The object of a totalitarian system is to destroy all forms of communal life that are not imposed by the state and closely controlled by it, so that individuals are isolated from one another and become mere instruments in the hands of the state. The citizen belongs to the state and must have no other loyalty, not even to the state ideology.”

Leninism, beginning when Lenin was at the helm, shared this vision of society with fascism, particularly its Nazi variant. Democracy, in the sense that the people were permitted a say in their government, was rejected out of hand by both movements. Both movements, with some difference in emphasis, sought to substitute for the boring and corrupt routine of “bourgeois democracy” a heroic monolithism in which the party and its leaders became the charismatic force around which the state was congealed. Hitler as the fuehrer was a traditional charismatic. The Bolsheviks were more unique in making the impersonal party itself the charismatic entity that all must adore and follow without question.

Tismaneanu explicates this concept of the party by quoting one of the younger Bolshevik leaders, Yury Piatakov:

“In order to become one with this great Party he would fuse himself with it, abandon his own personality, so that there was no particle left inside him which was not at one with the Party, did not belong to it.” The same author in 1918, channeling Ignatius Loyola’s catechism to his Jesuits: “Yes I shall consider black something that I felt and considered to be white since outside of the party, outside accord with it, there is no life for me.”

Tismaneanu returns repeatedly to his efforts to draw similarities and differences between the two totalitarian movements. He describes fascism as “a pathology of romantic irrationalism” and Bolshevism as “a pathology of Enlightenment-inspired hyperrationalism,” expanding this thought as:

“Fascism was no less a fantasy of salvation than was Bolshevism: both promised to rescue humanity from the bondage of capitalist mercantilism and to ensure the advent of the total community. . . . Both Leninism and Fascism were creative forms of nihilism, extremely utilitarian and contemptuous of universal rights. The essential element of their modus vivendi was the ‘sanctification of violence.’ They envisioned society as a community of ‘bearers of beliefs,’ and every aspect of their private life and behavior was expected to conform with these beliefs. Upon coming into power and implementing their vision of the perfect society, the two political movements established dictatorships of purity in which ‘people were rewarded or punished according to politically defined criteria of virtue.'”

He concedes that there are other avenues that lead back to Marx that do not share the exterminationist credo of Leninism: “It is not at all self-evident that one can derive the genocidal logic of the gulags from Marx’s universalistic postulates, whereas it is quite clear that much of the Stalinist system existed in embryo in Lenin’s Russia.”

Because of Lenin, he writes, “a new type of politics was born in the twentieth century, one founded upon fanaticism, elitism, unflinching commitment to a sacred cause, and total submission of critical reason by means of faith to a self-appointed ‘vanguard’ of militant illuminati.”

Tismaneanu concludes that Leninism both in its original form and its Stalinist child constitute a dead religion. But he observes that antidemocratic collectivism remains in the wings in various parts of today’s world. Many observers of the post-World War II rise of Islamic radicalism, including Bernard Lewis and Paul Berman, see this Islamic resurgence not as a simple revival of eighth century religiosity but a movement that has imbibed key organizational lessons from German Nazism, which exercised a powerful influence on the Arab East, particularly on the Palestinians, Iraqis, and Egyptians, and of Communist forms of organization. Tismaneanu points in particular to Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda and other exemplars of radical Islam, that, like the Leninists and the Nazis, seek to impose by force a complex of total regulation of individual behavior and the suppression of all competing religions, ideologies, and political practices.

John Gray on Why Liberals Are Reluctant to Acknowledge the Crimes of Communism

British philosopher and high-end journalist John Gray offered a lengthy review of The Devil in History in the January 2, 2013, issue of the Times Literary Supplement, concentrating on why contemporary liberals have retained a distinct sympathy for communism. Gray is widely regarded as today’s leading philosopher of pessimism, the heir of Schopenhauer. The reason is that he rejects the Victorian religion of progress and its twentieth century continuity in the liberal faith in social and human improvement, which provide the basis for the seemingly ineradicable liberal feeling that communism, unlike fascism, was a worthy goal gone wrong.

For some years I have held Gray in high esteem. He operates at a level above partisan politics. He has at various times in his life been on the left, on the right, and in recent years, back on the environmental left. He is a scholar of note in explicating and defending Isaiah Berlin, perhaps the preeminent champion of liberal democracy in an age that sought refuge in authoritarian alternatives. For Gray, there is progress in technology, but human nature, with all of its aggressive and xenophobic potentials, was formed by biological evolution 50,000 years ago and hasn’t changed in a few centuries of improved prosperity and health care.

Gray notes that Tismaneanu’s comparison of Leninism with Nazism is controversial in the West, where even the idea of totalitarianism as a common category for the two systems is contested as a Cold War invention. This denial, he says, is deservedly met with incomprehension by people who lived under the Communist system.

Tismaneanu had highlighted the Bolshevik term byvshie liudi (former people) as a designation for all those categories who were deprived of citizenship and of the right to get a state ration card to buy food. Gray comments:

“Denying some human groups the moral standing that normally goes with being a person, this act formed the basis for the Soviet project of purging society of the human remnants of the past.” “Former people” has an awful resonance with the Nazi term for the Jews, Roma, and gays: “life unworthy of life.” Whatever differences there were in the two systems, Gray adds, “the two were alike in viewing mass killing as a legitimate instrument of social engineering.” Both advocated and created a “system of unlimited government.”

Gray is also impressed by Tismaneanu’s point that by the late 1940s Communism embraced ethnocentrism, nationalism, racism, and antisemitism, thereby acquiring “some of Fascism’s defining characteristics.”

All the elements of exterminating unwanted categories of human beings were initiated by Lenin, who bore none of the pathological personal characteristics of Stalin, but simply a cold rationality. Gray writes:

“By their own account, Lenin and his followers acted on the basis of the belief that some human groups had to be destroyed in order to realize the potential of humanity. These facts continue to be ignored by many who consider themselves liberals, and it is worth asking why.”

His conclusion is that liberalism shares with communism “the idea that history is a story of continuing human advance,” an idea that he dismisses as “a hollowed-out version of a religious belief in providence.” While liberalism proceeds by modest reforms, he says that liberals “have seen the Communist experiment as a hyperbolic expression of their own project of improvement; if the experiment failed, its casualties were incurred for the sake of a progressive cause.” And finally, “Blindness to the true nature of Communism is an inability to accept that radical evil can come from the pursuit of progress.”

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.