Kate Millett, ‘Extraordinary Woman,’ Remembered By Steinem, Ono, and Clinton

November 10, 2017

Yoko Ono at Kate Millett memorial. (Photo: Mary Reinholz)

Feminist icon Kate Millett, author of the ’70s classic Sexual Politics, received a star-studded Manhattan sendoff on November 9, following her death September 6 in Paris at age 82. The Upper West Side memorial service drew about 500 people, most of them women, and sometimes befitted a state funeral.

Pamela Mataszewski, a blonde bagpiper in a kilt, began the service with a mournful dirge as she strode up the center aisle of a Unitarian Universalist Church to its altar where Millett’s ashes had been placed in a blue jug beside flickering candles. After she departed, still blowing her pipes, soprano Katie Zaffrann sang “Ave Maria” to mark the passing of Millett, who lived at 295 Bowery for 38 years, residing there when it was in a rundown neighborhood populated by so-called “Bowery bums.” Her late 19th century building once housed the infamous McGurk Suicide Hall, a spot where several teenage prostitutes were believed to have killed themselves by lacing their last drinks with carbolic acid.

Katie Zaffrann (Photo by Mary Reinholz)

In 2004, Millett lost her fierce legal battle to retain her immense two-floor loft. “The city evicted her from her home, kicking and screaming, and relocated her” nearby in the East Village, recalled Eleanor Pam, president of Veteran Feminists of America, which sponsored the service. “Kate embraced downward mobility,” cracked Millett’s friend of 60 years. “She was probably the only person in the world who believed that getting evicted from the Bowery was a step down.”

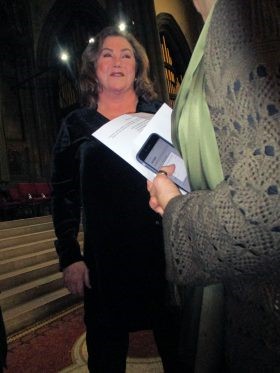

There was loud applause when actress Kathleen Turner, screen siren of the 1980s, delivered remarks from Hillary Rodham Clinton in her signature husky voice, quoting the former first lady and New York senator. Clinton’s comments lauded Millett’s “contributions to the women’s movement here and around the world,” referring to her as an “extraordinary woman” who had written a “unique work,” meaning Sexual Politics.

Kathleen Turner. (Photo: Mary Reinholz)

Turner next recited a lengthy tribute to Millett from poet Robin Morgan, editor of Sisterhood is Powerful, a well known 1970 anthology of radical second-wave feminist writings.

There were also spoken “reflections” on Millett’s life as an artist, writer, educator and activist by a lineup of prominent female speakers, among them Yoko Ono, who faced the crowd seated in a wheelchair. Ono, 84, honored Millett in 2013 with a Yoko Ono Courage Award for the Arts. Before she spoke, Ono told this reporter that she couldn’t remember when she first met Millett, but noted “it was a long time ago.” She told the mourners that both her husband John Lennon and their son Sean Taro Ono Lennon were feminists.

Gloria Steinem, 83, stood at the podium in black leather pants, calling Millet an original thinker who gave voice to “the most important ideals that animated the women’s movement.”

Steinem said that Sexual Politics revealed misogyny in writing by ostensibly liberated male authors like D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller and Norman Mailer, in a way that foreshadowed “all our work against rape, sexual harassment, prostitution, pornography and sex trafficking.” According to The New York Times, she quoted from a note penned by legal scholar Catherine MacKinnon who wrote that Millett “conceived the critique of sexuality as male-dominated from the bedroom to the boardroom to the potted plant.”

At that point Steinem asked of the gathering, “Don’t you kind of wish we could read Kate on Harvey Weinstein?” she said, stirring applause and laughter from folks who had clearly read reports of the disgraced producer allegedly masturbating into a potted plant. (MacKinnon’s reference to male dominance over a potted plant is interesting, especially since she and radical feminist Andrea Dworkin were controversial in the early 1980s for writing anti-pornography ordinances in two U.S. cities that were voted into law but blocked by city officials and court decisions deeming them a violation of free speech rights.)

Gloria Steinem. (Photo: Mary Reinholz)

As for Millett, Steinem described her more personally as “trenchant and funny, serious and zany.”

“She laughed at my jokes and tried to teach me how to fertilize Christmas trees,” added the co-founder of Ms. Magazine with a smile. She was referring to Millett’s sale of Christmas trees from her farm in Poughkeepsie. They were grown by bare breasted acolytes whose nudity reportedly sparked unease among some upstate neighbors, and then were sold by Millett in the Bowery, which is now decidedly gentrified.

Millett’s niece, Lisa Millett Rau, recounted how her aunt was able to buy the upstate farm which encompassed a women’s art colony because she “got rich” from Sexual Politics, a bestseller based on her Ph.D. dissertation at Columbia University.

The book landed the shy, Oxford-educated Millett, a native of St. Paul, Minn., on the cover of Time magazine. She soon “came out” as a lesbian after drawing criticism from gay women for identifying as a bisexual. Millet’s 20-year-marriage to sculptor Fumio Yoshimura ended around that time. She was wed to Yoshimura, whom she met in Japan, at the Unitarian University Church on Central Park West, according to Rev. Schuler Vogel, who gave the invocation. Shortly before her death, Millett married Sophie Keir, her longtime companion who also had lived at 295 Bowery.

Millett, a scholar, told me five years ago that she was unable to get a college teaching job. “I’ve always want to teach again, but they won’t let me,” she said during an interview at her new digs on East 4th Street. “First of all, I’m too old. And I’ve been fired from every university faculty. Barnard and also NYU. I’m always in Women’s Studies, but my politics are kind of different because I’m always on the side of the strikers. I’m always on the side of the teachers that get paid nothing at all.”

Millett’s memorial lasted more two hours, ending soon after photographer Cynthia MacAdams, a long time friend, recited Dylan Thomas’, “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night,” in a roaring voice.

The assembled sistahs and male sympathizers joined singer Holly Near and Joan Casamo in belting out “Bread and Roses,”a song based on a 1912 political slogan by successful striking textile workers in Lawrence Mass., and shouted a farewell salute as they exited the church. #

Bagpiper Pamela Mataszewski (Photo by Mary Reinholz)

A version of this story was first published in BedfordandBowery, a New York Magazine website covering downtown Manhattan.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.