Hudson Bell of Fern Hill takes Honey on an historic walk through San Francisco

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

Ina’s_house is by Feride B. Diri, showing Honey looking at Ina Coolbrith’s house on Broadway

Ina’s_house is by Feride B. Diri, showing Honey looking at Ina Coolbrith’s house on Broadway

Juan Bautista de Anza sited the fort called El Presidio Real de San Francisco on March 28, 1776. A year later, Jose Joaquin Moraga built the garrison, numbering 33 men. By 1825, the Presidio had 120 houses and perhaps 500 people, mostly women and children. The Mexican government recognized the Presidio as a pueblo in 1834. According to W. W. Robinson, relying on attorney John Whipple Dwinelle’s argument in the United States District Court case titled The City of San Francisco v. The United States (published as a book in 1863) by 1835 “ the population was shifting from the table land above the sea to the sheltered cove adjacent to Telegraph Hill where the table land above the sea to the sheltered cove adjacent to Telegraph Hill where the village of Yerba Buena was being born…. Until 1846 alcaldes and justices of the peace in Yerba Buena granted town lots to its inhabitants, the first conveyance being to William A. Richardson on June 2, 1836, of a 100-vara lot in the northwest corner of Grant Avenue and Washington Street.” For a year Richardson — a naturalized Mexican citizen — lived in a canvas tent, and then he built a house.

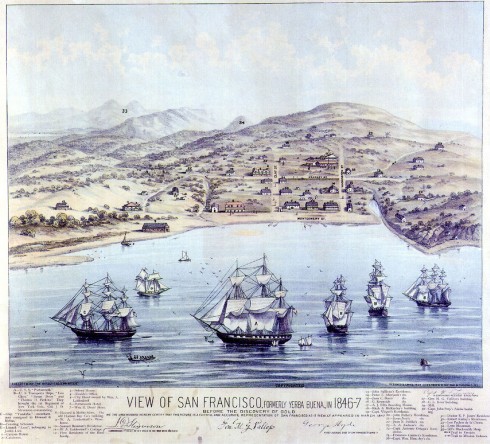

In 1846 a couple of hundred people inhabited the village of Yerba Buena. “Yerba Buena” is the Spanish name for a number of aromatic plants, most of which belong to the mint family. The plant grew in abundance adjacent to the Mission San Francisco de Asis, founded by Moraga and Father Francisco Palou in 1776.

The village inhabitants built a little wooden footbridge that year that crossed a small lagoon near the then Yerba Buena Cove, where Montgomery and Jackson intersect. There were about fifty buildings, many around Calle La Fundacion, a straggly dirt path up from the water.

Yerba Buena Cove watercolor (source unknown)

Yerba Buena Cove watercolor (source unknown)

On July 9, 1846, the USS Portsmouth, captained by Commander John B. Montgomery anchored near the town. The residents and the tiny Mexican force garrisoned at the Presidio watched Montgomery and a group of sailors, soldiers and marines land. They raised the American flag over the plaza, and that was the end of the capture of the town. Soon after, Sam Brannan arrived bringing with him 240 Mormons; none of them happy that the American flag now flew over what they had thought was a foreign country because of American persecution of Mormons. The Mormons doubled Yerba Buena’s population. Within two years, the population reached about 20,000 people from all over the world, and people kept on coming.

In 1848, Americans rushing to California’s gold mines came overland, or around the Cape of Good Horn, or they crossed the Isthmus of Panama or they came by way of Nicaragua. All of the ways to get to San Francisco were hard. The overland route took about six months. The water route took a little less time, depending on whether you could get on a steamer. A lot of people died getting to California to look for gold.

If the travelers arrived by sea they entered the San Francisco Bay and they saw mountains on the northern side that came down to the sea. The view opened, an island rock appeared that looked white: Alcatraz (“pelican”) for all the pelicans on the island. There was a small fort set in trees on a promontory. The town remained concealed by the promontory. The ship came closer to Alcatraz and the island of Yerba Buena, and the passengers saw vessels at anchor. They saw the peak of Monte Diablo thirty miles away.

Journalist Bayard Taylor wrote:

“At last we are through the Golden Gate – fit name for such a magnificent portal to the commerce of the Pacific! Yerba Buena Island is in front; southward and westward opens the renowned harbor, crowded with the shipping of the world, mas behind mast and vessel behind vessel, the flags of all nations fluttering in the breeze! Around the curving shore of the bay and upon the sides of three hills that rise steeply from the water, the middle one receding so as to form a bold amphitheater, the town is planted and seems scarcely yet to have taken root, for tents, canvas, plank, mud and adobe houses are mingled together with the least apparent attempt at order and durability.”

That town of adobe, canvas and planks built on sand hills is long gone. In 1847, the residents renamed it San Francisco. Between the beginning of the California Gold Rush and 1860 Yerba Buena Cove was filled in, and the downtown of the City of San Francisco built over it.

In the middle of this November, I took BART to San Francisco, emerged at Montgomery and climbed California Street to meet with Hudson Bell, the proprietor of Fern Hill Walking Tours at the fountain in Huntington Park on Nob Hill, my older daughter and my granddaughter, and four other urban history buffs.

The tour ambitiously covers Nob Hill, Chinatown, Russian Hill, Jackson Square, North Beach, Telegraph Hill, the Embarcadero and the Financial District.

Hudson provided us all with transit passes hooked to lanyards. I pressed the pass to a scanner on a trolley, a streetcar, and a bus – all crowded. All of the vehicles shook vigorously. The front seats are reserved for the elderly and the disabled. I sat. The tour was my 70th birthday present; I’m entitled to sit unless the age for “elderly” has changed recently. An Asian man with gray hair glowered at me until I rose and gave him my seat. I beamed at him from my shaky perch holding onto a strap. “Take it as a compliment,” my fifty-one year old daughter whispered. “I do,” I said.

Nob Hill

Hudson informed us Nob Hill was a post-gold rush suburb of the city up from Portsmouth Square, going back to the early1850s. The hill’s first name was California Hill, after California Street, which climbs its steep eastern face. It wasn’t known as Nob Hill until the 1870s, when the “nabobs” (or “nobs”) – the Central Pacific Railroad’s Big Four — built their mansions on it. Because the name is relatively new, and because none of the 1850s-era buildings survive, a myth has been created that no one lived on Nob Hill until the cable car ran up Clay Street in 1873.

We went first to the Fairmont Hotel, the location of Gertrude Atherton’s fundraiser for Ina Coolbrith after the 1906 earthquake and fires destroyed her home. We then went up to the Fairmont’s roof and had a panoramic view of the city.

We passed by the Flood Mansion – the brown stone, only surviving residential structure on the hill, dating back to 1885, redesigned and added to by Willis Polk circa 1915 for the Pacific-Union Club. Also in 1915, Polk oversaw the architectural committee for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. This year is the centennial. http://www.ppie100.org/events/.

We went inside Grace Cathedral (always around the hill since the gold rush). We later saw where the cathedral was — on the edge of today’s Chinatown.

Hudson showed us where the cable car originally ran up the hill on Clay Street.

We stopped at the location of where Ina Coolbrith’s family (the Pickett family) lived in the 1860s when she was the center of literary circle, the salon that influenced the founding of the Bohemian Club in the 1870s.

Chinatown

Today’s Chinatown is where the original downtown of San Francisco was in the Yerba Buena (Mexican) days.

We saw the location of where William Richardson built his tent structure in 1835, founding Yerba Buena, on the street that was once the dirt path called Calle de la Fundacion.

We Saw Portsmouth Square, the original Plaza of the city, otherwise known as the “cradle of San Francisco.”

We saw where the Custom House was located on the square, where Col. John Montgomery’s men raised the American flag in 1846 at the beginning of the Mexican-American War.

Hudson pointed out the Robert Louis Stevenson monument, which was 1st monument in his honor after his death. Designed by Willis Polk, the monument used to be in the center of the square, dating back to 1897. The sails of the vessel on the monument is gold, perhaps gold leaf, maybe very good gold paint, evocative of Stevenson’s adventure novel narrating a tale of “buccaneers and buried gold.” Stevenson drafted Treasure Island, however, in Monterey.

The inscription reads:

“To remember Robert Louis Stevenson – To be honest to be kind – to earn a little to spend a little less – to make upon the whole a family happier for his presence – to renounce when that shall be necessary and not be embittered to keep a few friends but these without capitulation – above all on the same grim condition to keep friends with himself here is a task for all that a man has of fortitude and delicacy.”

In 1876 Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson had met and fell in love with a married American woman – Fanny van de Grift Osbourne – in Grez-sur-Loing in France and traveled to Monterey to find her. On one of his walks near Monterey, he fell deathly ill. A sheepherder saved him and took him back to Monterey. Fanny’s husband telegraphed her to return to San Francisco, and Stevenson followed her. He rented a room at 608 Bush Street and often visited Portsmouth Square for the sunshine. Fanny divorced her husband and married Stevenson in 1880.

Jackson Square

A squiggle drawn in concrete between buildings indicates where Yerba Buena Cove waters once reached the village.

We saw the oldest commercial buildings in San Francisco, including the building that housed the publication Golden Era, San Francisco’s first literary journal, later a central telephone building, now a bank. These buildings survived the 1906 earthquake.

Russian Hill

We Ina Coolbrith’s home on Broadway where she lived when she was named poet laureate, the house the Bohemian Club paid to have built. It is a duplex. She lived on the second story and rented out the first. We also stopped at the place where pre-1906 her house once stood.

We passed by the first Bay Region shingle houses.

We saw home that Willis Polk designed and lived in 1890s, designed as duplex for his family, and the family of Dora Williams (widow of Virgil Williams, who started Art Association, and one of founders of Bohemian Club). Dora was a friend of Fanny Stevenson. Fanny moved back to San Francisco after Stevenson’s death and commissioned Pok to design a house for her near the top of Russian Hill on a site that once had a view to the Pacific Ocean. The house once faced a private park (Some of the immense cypresses are visible, looking east) and currently faces many thousands of tourists drawn by the crooked bit of Lombard Street. It recently sold for almost $15 million.

We walked through Ina Coolbrith Park.

We saw where Coolbrith lived following 1906 fires, until her new house on Broadway was finished.

Telegraph Hill

I don’t remember how we got to North Beach but we did, and then we took a bus up to the top of Telegraph Hill. Wealthy socialite Lillie Hitchcock Coit left the money to build a memorial to the firemen of San Francisco. At age 15, in 1858, she witnessed the Knickerbocker Engine Co. No. 5 respond to a fire call on Telegraph Hill and helped them to get to the top – calling out to bystanders for assistance. In October 1863, the engine companies made her an honorary member.

Hudson told us the tower was not designed to look like a fire hose. It looks like a fire hose.

The Coit Tower murals were done under the auspices of the Public Works of Art Project, the first of the New Deal federal employment programs for artists. Ralph Stackpole and Bernard Zakheim successfully sought the commission in 1933, and supervised the muralists, who were mainly faculty and students of the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA). The artists were committed in varying degrees to racial equality and to leftist and Marxist political ideas reflected in the mural.

We then went down the Filbert Street steps. The stairway is a public street. The lowest section is concrete and steel snaking up the side of a cliff that gives way to a wide concrete stairway. Reaching Montgomery Street, the steps cross the median with a short staircase. The upper section is nearly straight, running through a series of gardens.

The elegant Moderne Malloch Building located on a street, also reached by the steps, was the apartment building where the 1947 noir Dark Passage was filmed, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall (playing Irene Jansen). The film is initially seen through the eyes of Vincent Parry He has just escaped from San Quentin, a man wrongly convicted of murdering his wife. Jansen hides him in his apartment during his convalescence from plastic surgery. When she helps Parry remove his bandages, he looks in the mirror and sees that the quack has turned him into Humphrey Bogart, which was sort of a weird thing to do, but then aiding and abetting a convicted murderer was pretty weird. In one scene, he slowly and painfully climbs the Filbert Steps.

The film also showed a diner, long-closed, in the Fillmore District, cable cars, part of the Presidio, the underside of the Golden Gate Bridge, and the streets of San Francisco as they were in the 1940s.

Resources

John Whipple Dwinelle The Colonial History of San Francisco (Applewood Books, originally published in 1863)

http://www.fernhilltours.com/.

W. W. Robinson, Land in California (1948 University of California Press, Ltd.)

Bayard Taylor, Eldorado: Adventures in the Path of Empire (Santa Clara University and Heyday Books, 2000)

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.