How the LA Times After a Hundred-Year Love Affair with the City of Vernon Decided It Really Hated the Place All Along

A more balanced look at the industrial town’s history and at some of the (often ill considered) proposals for solving the Vernon problem.

By Leslie Evans

Vernon, California, is an odd little town. Five square miles of meat packing plants, warehouses, and industrial enterprises where 50,000 people work during the day while only 91, belonging to just 23 families, live at night. There are only 26 homes within the city’s borders, virtually all occupied by city employees or relatives of the long-serving members of the city council or other city officials.

Vernon, California, is an odd little town. Five square miles of meat packing plants, warehouses, and industrial enterprises where 50,000 people work during the day while only 91, belonging to just 23 families, live at night. There are only 26 homes within the city’s borders, virtually all occupied by city employees or relatives of the long-serving members of the city council or other city officials.

Vernon lies on the southeast side of Downtown Los Angeles, bounded roughly by Washington Blvd. on the north and Slauson on the south. Its main arteries are Santa Fe Avenue, Soto Street, and Bandini Blvd., the last best known for the fertilizer company of the same name.

If you first read about Vernon in 2005, the last five years would be one unrelieved story of municipal scandal. In April of that year the Los Angeles district attorney issued search warrants at the Vernon city hall in an investigation of alleged misuse of public funds. Boxes of files were seized. A year and a half later, in November 2006, indictments were handed down against long-time mayor Leonis Malburg, city administrator Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr., and several other city officials. The charges mostly amounted to payment of very high salaries and bonuses to the elderly coterie who run Vernon, as well as charges that several, including the mayor and Malkenhorst, live outside of the city, making their votes in the small industrial town illegal.

The scandal soon became conflated in the press and the public mind with another story of municipal corruption in the nearby town of Bell, which shares a border with Vernon. In Bell the mayor and other functionaries also gave themselves supersized salaries. Yet there were differences that were soon lost in the general sense that unrestrained criminality was afoot. Bell, a town of 36,000, mostly very poor Latinos, was virtually bankrupted by secret salary raises, illegal taxes, and secret deals between city officials and businesses that they owned, leaving the city with huge debts. The citizenry rose up in fury and were ready to show up with the traditional pitchforks and torches to administer vigilante justice. In Vernon by contrast it was only the outsiders who got excited. The town is one of the most prosperous in the region.

The handful of well paid city employees, enjoying practically giveaway rents, are the last ones to raise a protest. Even the 1800 businesses in the industrial burg generally love the place, and while they wanted the big salaries reduced and some new leaders, they have consistently resisted the more extreme proposals of Los Angeles city and county politicians to dissolve the city altogether, or the ill-thought-out proposal of the County Board of Supervisors to strip the city of control of 90 percent of the tiny housing stock, which would be likely to open the rich little town to a takeover by genuinely criminal elements far worse than the current leaders.

Below I will take up the current scandal and critique the LA Times’ recent revisionist history of the small town, which will provide a clearer basis to look at the various proposals to solve the Vernon problem.

The Los Angeles Times has in large part played a negative role in the Vernon scandal. It was of course a very good thing for the Times to expose the excessive salaries of the Vernon officialdom. And no one can deny that the problem is significantly inherent in the founding structure of the city, as a peculiar hybrid between a city and a private corporation. Yet because the roots of the problem lay far in the past the Times gave in to the temptation to raise a lynch mob atmosphere against the town by retrospectively painting its whole history as one of criminal malfeasance. This view, asserted extremely forcefully in the Times in the years since 2005, is simply not supported by its own archival coverage, both on a factual level and in the overwhelmingly positive opinions the Times regularly expressed toward Vernon during its first 100 years. The Vernon leadership may have always been the self-perpetuating dynasty of its two founding families, and that may not be how any normal city is run, but for a century the Times, with a few rare exceptions regarded the founding families as good stewards of an industrial park essential to the economic well-being of Los Angeles city and county and responsible for providing tens of thousands of badly needed jobs.

The Unfolding Vernon Scandal

The investigation of the Vernon officialdom began in 2005. Five years later much of the investigation is still in process with very little of it finding enough of a smoking gun to end in a courtroom. The charges were not in themselves particularly egregious, though they could potentially carry long jail terms. The salaries were without question extremely high for town government officials. Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr., was making almost $600,000 a year in salary and bonuses, plus perks such as city-funded limousine service and first class foreign travel. The accusation has been raised that some of this money was illegitimately for personal use but no indictments have been issued years into the investigation. Deputy city attorney Eric Fresch was paid nearly $1.65 million in salary and hourly billings in 2008. Extreme but not in itself illegal, and far less than corporate CEOs and staffs, which as we will see is in some sense what the Vernon officialdom actually are. City administrator Donal O’Callaghan has been charged with conflict of interest for getting his wife a city job.

A number of the Vernon officials were charged with voter fraud, including Mayor Leonis Malburg and his wife, Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr., and a few others. This is for giving a false address to vote in a district where you do not live. It can be prosecuted as either a felony or a misdemeanor at the discretion of the district attorney. This has been a century-long issue for Vernon. As the town is an industrial park with virtually no residential section, its leaders always mostly lived elsewhere, commuting to work and voting in the town. Los Angeles has become fussier about this violation in recent years and initiated several cases against LA politicians, but they have never led to the kind of severe punishments the statute nominally permits. Los Angeles County Supervisor Yvonne Braithwaite Burke, when found in 2007 to be living in a Brentwood mansion instead of the low-income area she represented, escaped charges by retiring. In 2010 Los Angeles City Councilman Richard Alarcon and his wife, as well as California State Senator Rod Wright, were all indicted for giving false addresses on their voter registrations. It is doubtful any of these public servants will do any jail time.

The Bizarre 2006 Election

The Vernon investigation of 2005 was inflamed by a surreal election fiasco that began in January 2006. Eight strangers — the town is small enough so everyone knows who is a stranger — moved into a five-room industrial building and within a few days three of them filed applications to run for the five-member city council. If elected they would have commanded majority control over a city with a $300 million annual budget. The town’s microscopic voter base meant that any challenge had some potential to unseat the incumbents and take control of a city on which some 1800 industrial companies and commercial operations depend. The unorthodox living arrangements had been secured by Chris Summers, described by the LA Times as “a disbarred attorney who has been convicted of embezzlement and forgery.” The Times added that Summers had a long-time lucrative relationship with Albert Robles, “a convicted felon who as treasurer of South Gate nearly bankrupted that city.” Terrified that this unsavory crew could recruit and register fifty or sixty people to come in and vote to take over the town, the geriatric Vernon leadership grossly overreacted.

Charging that the building had been occupied without the owner’s permission, the city council had city police break the locks and evict the eight squatters. The would-be candidates were met by Albert Robles, who was seen giving one of them $100. They then took up residence in an Alhambra hotel, and showed up to vote on April 11. City Clerk Bruce Malkenhorst, Jr., canceled the eight new voter registrations and locked up the ballot box while the case went to court. Meanwhile the town hired clumsy private detectives to ostentatiously shadow their new opposition.

The case took an ominous turn when the county registrar ruled that canceling the voter registrations was illegal and that even homeless people had a right to register to vote. With that ruling the future of Vernon was placed in doubt, as any well-funded speculator could probably find seventy homeless people they could pay to bus into Vernon to outvote the 60 registered residents.

A word here about Albert Robles, the reputed mastermind of the effort to capture a majority on the Vernon city council. The Times devoted a single sentence to this character while aiming many columns of vitriol at the current Vernon leadership. Without glossing over the evident greediness of the Vernon elders, they have never been accused of doing a bad job of running the little city, which is free of debt, has a model police force, its own health department, and is even by the Times’ accounts, remarkably efficient, with the lowest electric rates in the state, clean streets, and graffiti free. The Times in the four years of its hostile coverage following the 2006 election has been remarkably unconcerned at what the city would likely have become if the takeover effort had succeeded. Robles is a former mayor, councilman, treasurer, and deputy city manager for the city of South Gate. According to the Wikipedia, “Robles was indicted on federal corruption charges in 2004. This stemmed from his award of contracts worth millions to friends and business associates as well as funneling money through the awarded contracts to himself and family members. He was found guilty of 30 counts of bribery, money laundering, and depriving the electorate. He was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison and ordered to pay the city of South Gate $639,000 in restitution.” Nothing remotely on that scale has been charged against the Vernon political coterie and it doesn’t take much imagination to see that the aim of the electoral challenge had little to do with democracy but was a gambit to loot the lucrative town treasury.

In October 2006 Judge Aurelio Munoz ruled that the ballots must be counted. Vernon complied, no laws were broken, and the incumbents were reelected. But the heavy handed methods they had used, exacerbated by the very high salaries they were revealed to be paid and the several who lived out of district but voted in the city, opened up a firestorm.

“Almost since Vernon was established . . . the town has moved from controversy to controversy”

The LA Times, which for the previous hundred years had been an enthusiastic promoter of the little city, now saw nothing but evil there and developed an astonishing case of amnesia about its own past coverage, now seeing a century of corruption. An editorial in the April 14, 2006, issue headed “Infernal Vernon” fumed: “HISTORY HAS SHOWN THAT there is no election the city of Vernon will not cancel, disrupt or simply ignore if there is even the possibility it will not benefit the handful of families that have mismanaged the city for a century.”

Hector Becerra, who has emerged as the Times’ point man on the trash Vernon campaign, with backup from two other Times reporters, filled in this indictment in a lengthy June 18, 2006, article.

“Almost since Vernon was established a century ago,” Becerra et al. wrote, “the town has moved from controversy to controversy.” The article then launches into a supposed history of Vernon that is wrong or tendentious on numerous counts. First, it singles out John B. Leonis as THE founder, presumably because he was a colorful character and makes a simple and easily grasped link to the current scandal-plagued mayor, Leonis Malburg, who is John Leonis’s grandson.

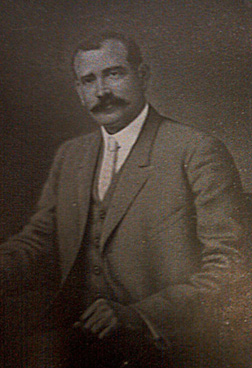

John Baptiste Leonis

John Baptiste Leonis was a French Basque immigrant and an important figure in Vernon’s first half century, but he was never the town boss. A word here about Vernon’s founding, as it contained within its initial charter all the issues that made the city praiseworthy for its first century but which are now the basis for condemning it. The idea came from Leonis, who ran a general store amidst numerous pig farms. Leonis persuaded two brothers who owned one of these farms, James and Thomas Furlong, to go in with him in turning their land into what would today be called an industrial park. They in turn persuaded a majority of the other nearby farmers to pool their land and incorporate in 1905 as the city of Vernon.

From the outset Vernon was chartered under the motto “Exclusively Industrial.” That meant exactly what it said: It was going to be a city with essentially no residential district, exclusively devoted to serving industrial properties. That meant from the outset that Vernon was an unusual hybrid, part city but in large part a corporation that leased or sold land to factories and warehouses to which it provided many services. And like any corporation, its owners, who initially also personally owned the land on which the city was built, would remain in office indefinitely. It is not true, as the Times has it, that Vernon was born in controversy over this organizational form, which is self-evidently at the heart of the essential charges against it today: that the leadership is self-perpetuating and pays itself corporate-style salaries, that the few residents are essentially employees rather than citizens, and that a number of the city officials live in actual residential parts of town rather than among the slaughterhouses and factories that make up almost all of Vernon. It was only in the twenty-first century that the forms required of a city came to be seen as incompatible with what was in essence the private ownership of the town.

Becerra sets out to prove his charge that Vernon was beset by controversy “almost since [it] was established” with this first salvo:

“A powerful voice on the town’s Board of Trustees,” [the mayor, who held the strongest single power in the city, was James Furlong from 1905 to 1941], “Leonis initially promoted activities that other jurisdictions spurned: gambling, prizefighting and drinking. He leased land to a saloon owner who opened the ‘longest bar in the world.’ On one side was a boxing stadium; on the other, a baseball stadium.”

Becerra suggests a scene of small scale squalid depravity run by lowlife hustlers. Let’s look a bit at this sin city. Note that Leonis became rich by creating a bank and he later owned a stockyard and feed mill. He was not an owner of any of the night life establishments for which Vernon was, in fact, famous during its early days, though he had the vision to bring in promoters who made the little town a center of Los Angeles night life.

There were some brothels in the early days, as there were in other cities, including Los Angeles, but Vernon closed them down in 1913. The gambling, such as it was, took place at Baron Long’s Vernon Country Club. This was the one Vernon institution the LA Times campaigned against during those years, mainly because the paper didn’t like strong drink in the period leading up to Prohibition and Vernon was, along with Venice, California, one of the two “wet” towns in the county. The gambling issue came to a head in February 1916, a decade after the town’s founding, when Harry Ellis Dean, a former county deputy chief district attorney, persuaded a justice of the peace, acting in the mistaken belief that the DA’s office had authorized it, to issue an arrest warrant for Baron Long on charges of illegal gambling. The actual county district attorney, Thomas Lee Woolwine, refused to prosecute, saying the gambling in question “was in the form of ongoing contests of a sort long conducted by various businesses. Though technically games of chance, they ‘had been allowed to run on the theory that they were within the law’” (2007 Metropolitan News Company story, the internal quote is from an LA Times article of the period). The Vernon Country Club was destroyed in a fire in 1929, when the Times described it as “one of the most popular dining and dancing resorts of Los Angeles county” (March 1, 1929). Baron Long went on to become the owner of the Biltmore Hotel.

From Hector Becerra’s disparaging dismissal of the anonymous “saloon owner” and passing references to prize fighting and baseball the reader would never suspect the central role little Vernon played in Los Angeles sports and night life in its first two decades. The unlikely rise of a mainly industrial park into a major center for Hollywood celebrities and the high-life crowd was due to three men: first of all, the “saloon owner,” Jack Doyle, and Vernon meatpackers Peter and Edward Maier.

In a case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing, Times sportswriter Steve Springer in 2006 gave a more honest account of Vernon and area sports:

Boxing at Jack Doyle’s Vernon Arena, 1927

“Before football came and went, before the Dodgers and Lakers, boxing was the center of the Los Angeles sporting world. . . . The city of Vernon was the first focal point for the sport in the Los Angeles area, thanks to a bartender and former railroad worker named Jack Doyle, who opened a training camp in Arcadia in 1908 . . . . Two years later, when he opened a bar in Vernon, Doyle decided boxing would be a great vehicle for getting customers into his establishment. So he began to stage four-round fights, the participants lined up by matchmaker Wad Wadhams.” (March 30, 2006).

Boxing began in Vernon shortly after the town was founded in an outdoor arena run by Tom McCarey but it took off in a big way after Jack Doyle opened Jack Doyle’s Central Saloon in 1910 at the corner of Santa Fe and Joy Street. It did have a 100 foot bar, with 37 bartenders. He built a small arena next door, which he replaced in 1923 with a 7,000 seat stadium that the Times described as “the finest U.S. indoor arena” (January 1, 1924). While it was being built the paper enthused:

“The manly art of self-defense has a prestige at present in Los Angeles that is hardly second to that of any other city in the Union. True, we are not allowed to swing but four-round bouts, but these short session affairs have become a fad and in many cases are more replete with torrid action than are the longer tilts in the East. So popular has the game become in the last year or so that the home of the four round sport in Southern California — Vernon arena, if you please, is absolutely too small to accommodate the fans when an enticing program is offered.” (July 13, 1923)

Doyle in his day was a nationally famous fight promoter and many world championship bouts were held at his Venice Arena. Jack Dempsey fought there in 1924.

The second major sports development was the creation in 1909 by Peter and Edward Maier of the Vernon Tigers, a Pacific Coast League baseball team. The team was bought in 1919 by Hollywood star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, and won the PCL pennant in 1920 over the Seattle Indians. After being moved to San Francisco for a while the team came back to Los Angeles under the name the Hollywood Stars, where it lasted until 1958.

To try to sort out truth from fiction, in research for this article I did a search of the Los Angeles Times archive for the word “Vernon” in article headlines from 1905 to the present. This turned up 4006 articles. The vast majority were about the city of Vernon. I went through year by year looking at each headline, reading the free abstract wherever it bore on the issues we are looking at, and paying to see the full text of scores of articles on the Times pay-per-view archive. What this revealed is that far from Vernon being a center of controversy “almost since [it] was established,” the Times poured out ink over two decades covering Vernon sporting events and little else about the town. Typically the paper ran 180 to 200 articles a year about Vernon, most about boxing matches, or under titles such as “Vernon Tigers Gnaw the Sacramento Solons.”

There is an occasional denunciation of Baron Long or a note that some industrial plant has been built, but sports is not just the main but virtually the only subject worth covering. The sports ended when the Tigers were moved to San Francisco in 1925 and Jack Doyle became the fight promoter for the Olympic Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles in 1927. With sports gone the Times lost interest. In 1930 the Times ran only 5 articles on Vernon, mostly on industrial construction.

What today’s Times reporters don’t seem to want to recall is what the Times actually thought of Vernon the city. It was not scandals of supposed mismanagement. A good sample comes from the January 1, 1915, Times, under the headline “Vernon –The Coming Industrial and Manufacturing Center of Los Angeles County.” This gets us to something else that is objectionable in the Times’ coverage of the recent five years. Vernon consistently comes across as a little no-account burg whose only interest is as a negative example of a historically bad leadership. It is always mentioned that Vernon is an industrial enclave, but the tone invariably suggests that it is not an important place except for concern about its bad government. In the genuine history of our area Vernon was the keystone of Los Angeles industrial growth and remained indisputably so until the incorporation of the City of Industry in 1957. The Times, singing a song that it would reprise many times over the next ninety years, added in its 1915 article:

“One of the greatest factors for real progress and prosperity in Southern California for a decade or more has been the industrial development in the … manufacturing suburb of Vernon.”

An Expose That Wasn’t

Hector Becerra doesn’t find his first supposed nugget of scandal until twenty years after the city was founded. No scandal in twenty years wouldn’t be bad for most cities. Here is how he tells it:

“In 1925, The Times did its first front-page expose of Vernon. The paper quoted one foe as saying of Leonis: ‘In that town, you do not file papers at the City Hall. You simply hand them to John and he puts them in his pocket. If he is in favor of the proposition, it goes through; if he is opposed, that’s the last you hear of it.’”

By definition an expose is a revelation of wrongdoing, crime, or corruption based on FACTS. When we look at the actual piece Becerra and his team refer to, dated June 19, 1925, it doesn’t claim to be any of those things. It merely quotes an unsupported opinion by one of John Leonis’s enemies on which the Times ventures no opinion of its own as to its truthfulness. Becerra retails this stuff as fact eighty-one years later, with all the principals long dead, maybe thinking no one will bother to go back and read his source. Sorry, fella. The article is headlined “Vernon Run by One Man Is Protest.” The “foe” Becerra doesn’t name was John T. Gaffey and the occasion was a long-simmering court battle over a piece of land that Vernon had wanted to annex. Gaffey was not a resident of Vernon but was a wealthy real estate developer in San Pedro. He was married to the richest woman in California, Arcadia Bandini, heiress of a Spanish land grant and worth some $8 million. Vernon ultimately did not get the land.

Gaffey was prominent in area politics, having served briefly on the LA City Council and the Board of Equalization. But he was also convicted in 1915 of overcharging the residents of Palos Verdes for their water, which he controlled, and compelled to make restitution, so he was no saint. No reputable reporter would present Gaffey’s unsubstantiated outburst during a land fight as fact, but Becerra does just that. The Times back in 1925 also asked John Leonis to respond:

“When Leonis was told of Gaffey’s statements, he laughed and declined comment. ‘Just let him have his say; I don’t care to answer him.’”

Note that Gaffey in the quote from the Times does not claim to have given Leonis such a paper, or even to have witnessed anyone else do so, nor does he say from whom he heard this story. This makes Becerra’s effort to slip the quote in as allegedly part of a factual “expose” a con job.

The 1943 Legal Case

The first time the issues that presented themselves in the last few years came up was in 1943, thirty-eight years into Vernon’s existence. Not exactly a story of perpetual and unrelieved mismanagement and scandal. Becerra reports that a county grand jury indicted six Vernon leaders, including John Leonis, on charges of voter fraud and that four were convicted while Leonis and one other were acquitted. It would have been more useful to the present debate over Vernon’s future to have examined more closely the legal debate in the 1943-44 case. The Vernon functionaries were defended by John W. Preston, a former justice of the California Supreme Court. The charges for each of the accused hinged entirely on the pretty much undisputed fact that the six regularly voted in Vernon while living elsewhere, much the same situation recently charged against Vernon mayor Leonis Malburg and city administrator Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr. The court verdict, delivered in January 1944, was strangely split in seemingly identical situations. The police and fire chiefs, a city councilman, and the deputy city clerk were all convicted. They were given token fines of $500 each and permitted to keep their city jobs. They did not move into the city. Leonis, who had become mayor in 1941 on the death of James Furlong, and Thomas J. Furlong, the city clerk, both had the charges dropped outright, with the approval of the prosecutor as well as the judge (there was no jury).

There was no dispute over the fact that Leonis lived at 647 S. Hudson Avenue in Hancock Park, while Furlong, along with his son, Robert Furlong, who would succeed Leonis as mayor in 1948, lived on Van Buren Place in the West Adams section of Los Angeles.

So why were the charges dropped? In a January 19, 1944, editorial, the Times said that the judge had agreed with the defendants that Vernon was basically not a residential city and that “technical residence” through working there on a daily basis was sufficient to establish voting rights. Thus the issues that seem so clear to the Times and local politicians in 2010 were not at all clear to the legal system when they first came into a courtroom, in 1943. The Times in its 1944 editorial objected, not that the setup in Vernon was illegal or should be abolished, but merely that a nonresident officialdom risked getting out of touch with the town it administered:

“Since Vernon is a ‘city in which nobody lives,’ except technically, it has in effect been run by carpetbaggers. This is not a healthy situation. The decisions in regard to the Mayor and the City Clerk are presumably good law. But it would seem to be good practice to require the principal officials of any city to reside in it actually and not merely technically. Nobody can know what is going on in a town unless he spends most of his time there; staying there just in business hours is not enough.”

John Leonis was far from the feudal lord of Vernon that the Times painted him during the 1943 legal case or Becerra does today. He became mayor only reluctantly despite serious illness in 1941. He tried, before he retired in 1948, to persuade the Vernon city council to let him build a gambling casino, like the ones then in Gardena, on a piece of land he owned that had been a slaughterhouse. He was opposed by council member Judith Furlong Poxon, James and Thomas Furlongs’ sister, who had been a founder of the famous Vernon-based Poxon Pottery company. Judith won and Leonis didn’t get his casino. (July 10, 1994, interview by Jennifer Charnofsky with Father Philip Conneally, a nephew of Thomas J. Furlong’s wife, Kate Conneally Furlong.)

Leonis died in 1953. He had been succeeded as mayor in 1948 by Robert Furlong, the son of Thomas J. Furlong, who was reelected repeatedly until his death in 1974 and never the subject of any scandal.

Later Legal Challenges to the Vernon Officials

The courts occasionally returned to the Vernon conundrum in the years that followed. Not persistently and uninterruptedly as the Times writers try to imply but more like once in a generation. And until 2009 their efforts were even less conclusive than the 1943-44 trial.

Thirty-four years passed after the 1944 case before the issue of nonresident officials voting in Vernon was raised again. By this time the mayor was Leonis C. Malburg, John Leonis’s grandson, who was to become the focus of the 2005 scandal, still in office then and only the town’s fourth mayor. A Los Angeles County Grand Jury in December 1978 indicted Malburg along with City Administrator Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr., and City Attorney David Brearley. The case was intimately tied to a dispute with the 101-member Vernon Fire Department, who were on strike. One of the firemen, Carlton Claunch, filed to run for the Vernon city council and began a lawsuit against Malburg, charging him with holding the office of mayor illegally because he didn’t live in the city. The indictment against Malburg was for voting in Vernon while living in his grandfather’s former home in Hancock Park; against Malkenhorst and Brearley for having allegedly held up renewing a contract with the Vernon fire fighters until they agreed to withhold support from Claunch and to repudiate his lawsuit. The charges were not criminal and if they had resulted in conviction would have removed the defendants from office but did not include any threat of jail time.

In the end the court decided that the whole thing was part of the dispute over the fire fighters’ contract and dismissed the cases against all three, which never went to trial. A contract was signed in November and the dispute with the fire fighters was said to have been amicably resolved. Not much there to stir the scandal pot.

I would add that the judge could not have seriously believed that Malburg, who had inherited $8 million from his grandfather, really lived in an apartment over an office building in Vernon rather than in his 7,371 square foot Italianate mansion on Hudson Avenue in Hancock Park. Back in 1944 the court had actually confronted the issue and ruled that “technical” residence by working there was legal for voting. The court in 1978 dodged it entirely, presumably not thinking it a good idea to shatter the government of an otherwise well-run town that was important to the economic health of the region over what was essentially a misdemeanor, especially as there was pretty much no residential section of Vernon.

What Can Be Put on the Plus Side?

In its “Infernal Vernon” editorial the Times had opined that the city had been “mismanaged . . . for a century.” That judgment would have come as a surprise to its own editors who covered the Vernon beat over that hundred years.

In truth, apart from the sports coverage of the early years and the once-a-generation voting scandals that petered out without much issue, the Times’ rare coverage was almost all about new enterprises, investments, and the occasional fire or industrial accident. In October 1961 a piece on Vernon’s shrinking population treated the city with great friendliness, noting that it accounted for 10% of the employed population of metropolitan Los Angeles and contributed $9 million in annual taxes to the LA school system. It quoted a resident as saying “Living here is like living in a small country town. You know everyone. You feel you really have a voice in government. And you know your vote really counts.” This doesn’t fit well with the image of the recent past of a serflike handful of city employees afraid to open their mouths.

In July 1962 there was a still more adulatory article, headed “Industrial Park Idea Typified by Vernon” that lauded the idea of dedicated industrial parks devoted to industry and separated from residential areas, declaring Vernon “the pioneer, the granddaddy, and still the biggest of them all.” It praised the small city for “putting up modern public buildings, and … expanding its water and other public utilities systems.” The writer noted that the entirety of Vernon is zoned for industry and “There is not one hotel or motel in Vernon,” not to mention movie theaters or stores. But the Times saw that as a good thing then:

“Perhaps it is because of rather than in spite of these oddities in a municipality that Vernon is so ably fulfilling its chosen role of handmaiden to industry. It is a role which seems destined to become even more important as its facilities and the region develop.”

It was a decade later before the Times got back to the little town, this time with an article on how industry was being replaced by less profitable warehouses as factories aged and new ones wanted more space in outlying suburbs (July 20, 1975). It said “there are more of Fortune Magazine’s top 500 businesses in the city than in any other comparable area in the nation.” The writer reminisced a bit on the old sporting days, even having a good word for Baron Long’s Vernon Country Club, demonized by the Times back in the day and part of the stuff the present-day Times dismisses as scorned by neighboring towns:

“Baron Long’s sprawling Vernon Country Club became a gathering place for silent screen stars like Charlie Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino and Blossom Seeley.”

The 1975 piece had nothing but good to say about the place, how it had the only municipal health department in the county, “designed to help industry solve problems of food handling, noise, dust, fumes and internal environmental quality control.” And a police department that “claimed the average response time is under two minutes.”

Another twenty-five years on, the Time ran another general article about Vernon, in its April 4, 2000, issue. The subhead read: “Amid the factories and industrial odors of Vernon live 85 people who seem perfectly happy with their lifestyle.” Yes, elections are routinely canceled, but that’s “because incumbents rarely are challenged.”

This one is worth quoting at length to get a picture of the bucolic paradise the Times found there:

“Residents say that living in the 5-square-mile industrial city takes some getting used to. They have to put up with heavy freight trains that rumble through the city at all hours and the pungent fumes from factories, like the Farmer John pork processing plant and Kal Kan’s dog food factory. Still, Vernonites say they are a content group who share a sense of community rarely found in Southern California’s urban sprawl. What other city can hold an annual picnic that is attended by nearly every resident? How many cities have a mayor who can name almost every citizen?

“‘It’s like a big family here,’ said Isabel Saenz, who has lived in Vernon for 30 years with her husband, Edward, a water department employee. Their teenage granddaughter, Lorena Saldana, lives with them. . . .

“The utility fees are the lowest in the state and the subsidized rents are cheap, allowing some residents to save up to buy a house elsewhere. A three-bedroom house with wood floors, a backyard and a two-car garage is only $225 a month (if you don’t mind living a block from a railroad line). The commute for workers who live in the city is practically nil, and city employees work only Monday through Thursday.

“Maria Kirkland and her husband, Curtis, an electrical technician, recently moved from Fontana, where they paid $1,300 a month for a four-bedroom apartment. In Vernon, they pay $145 for a well-maintained one-bedroom apartment.”

Well, mismanagement, especially of the infernal variety, must be a bit in the eye of the beholder.

What Should We Do with Vernon?

An important part of the Vernon old guard were swept away following the 2005-06 scandals. Leonis Malburg was forced from office, sued by Vernon for legal fees, and convicted on the voter fraud count, for which he received probation and the hefty fine of $500,000, though for a multimillionaire it is not going to break him. There is a new mayor in town for the first time since 1974. His name is Hilario “Larry” Gonzales.

City Administrator Bruce Malkenhorst, Sr., resigned, as did his son, Vernon city attorney Bruce Malkenhorst, Jr. These and others who bit the dust – Eric T. Fresch, former city administrator and deputy city attorney; Donal O’Callaghan, former city administrator and utilities director; Roirdan S. Burnett, city treasurer/finance director; Jeffrey A. Harrison, former city attorney – were named in an October 21, 2010, subpoena by California’s attorney general and new governor Jerry Brown. This was aimed in large part at investigating and seeking to reduce the huge pensions these recently deposed Vernon officials are now collecting, in Malkenhorst, Sr.’s case, $500,000 a year.

Brown, sensibly, declared, “It’s clear to me that we need a state authority to set some standards and curb these excesses.” Setting statewide standards for municipal pay is an excellent idea, particularly for a town like Vernon where, while the town remains prosperous, the electorate is essentially hand picked by the town officials, or Bell, where the officials operated in secret to loot the treasury.

Meanwhile a plethora of more extreme solutions are being debated to solve the Vernon problem. Probably the most widespread is a call to disband the city entirely. This has been backed by Los Angeles City Councilmember Janice Hahn, who has introduced a motion to that effect in the LA City Council. This solution has been endorsed by LA County District Attorney Steve Cooley, State Assembly Speaker John A. Perez, and state Senator Hector De La Torre of South Gate. No city in California has ever been disincorporated against the will of its residents, and in the nation as a whole there are only a handful of such cases, the best known where a landowner in Ohio incorporated a “city” to create a speed trap for motorists, hardly comparable to the Vernon situation. In any case such a move would require an act of the state legislature that would also require majority support in a general statewide election, as one city cannot unilaterally decide it wants to gobble up another. Los Angeles, which does not even have a common border with Vernon, is not the only candidate for such a merger. The contiguous towns are Huntington Park, Bell, Maywood, and the City of Commerce.

None of these are a very good match. Bell should be out of the question as its own government is in shambles. Huntington Park and Commerce at first seem plausible, the former with 61,000 residents, the latter with 13,000, so they wouldn’t have elections that could be captured by seventy outside plants. But here the positives end. Both have high poverty rates, with median income in Huntington Park at $29,844 and in Commerce at $34,000, posing a strong temptation to divert large amounts of funds from the Vernon part of the merger to use for pressing needs in the other partner. Nor does either town have the health, fire, or police resources that make Vernon safe for the dangerous industrial processes that are housed there.

Huntington Park has its own police department but depends on the county health department for fire and health coverage, the last mostly through a health service center in yet another city, Whittier. Commerce has no health, police or fire departments, depending on the county for all of this.

In Commerce the largest employers are a casino, LA County itself, Smart and Final, and the 99 Cent stores, hardly in a league to run Vernon’s demanding 1800-firm industrial base, many of which are Fortune 500 companies.

The Vernon business owners have been outspoken as angry at the huge salaries but quite understandably opposed to dissolution or merger of their city, given the virtually certain negative effects that would have on the level of police, fire, and health protections they could count on, not to mention the 40 percent boost in electric utility rates.

Still, it would seem very risky to leave Vernon with its present microscopic residential sector and large city income, especially if the probably illegal restrictions on residence and voting the old guard insulated themselves with are removed, leaving the town a sitting duck for fast buck takeover attempts.

Steve Freed, president of the Vernon Property Association, told the Times that “Many business owners feel that the only way the city of Vernon can truly have a representative government would be for the property owners to be allowed to vote in city elections.” That is not currently permitted in any California city. But it is not so out of reach as a solution as it might seem. The National Conference of State Legislatures in the October 2008 issue of its newsletter carried a lead article entitled “Nonresident Property Owners and Voting in Local Elections: A Paradigm Shift?” It reported that ten states – Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming – have authorized cities at their discretion to grant voting rights to non-resident property owners in local elections, though in some cases these are restricted to voting on taxation issues. It adds that there are taxpayer associations agitating for such nonresident voting rights in Florida, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont, and Wisconsin. The article concludes:

“‘Taxation without representation’ was the cry that started a revolution. More than 200 years later, it is still fueling a debate that could affect a shift in election law.”

The city of Vernon was long aware of the problem of its structure with little or no residential housing and hence no independent voter base. The town at its incorporation in 1905 became what is called a sixth class city, which means it has no authority to write its own statutes. In 1953 Robert Furlong, during his tenure as mayor, attempted to resolve the issue that later lay at the heart of scandals in the next century. He formed a committee of Vernon businessmen that proposed to the California State Assembly a constitutional amendment that would convert Vernon to a chartered city, which does have such authority, and that it explicitly include in the charter a provision that nonresident property owners be permitted to vote in city elections. Furlong argued that Vernon at that time, despite its small population, was the state’s eighth largest city in assessable wealth. The proposal was approved by the Assembly Committee on Constitutional Amendments. The bill was defeated in the Assembly in May 1955.

It would seem to me that if the political system decides to go further than Jerry Brown’s proposal for statewide regulation of municipal salary limits to curb the financial abuses in towns such as Vernon, that another effort to give cities the choice of establishing enfranchisement of nonresident property owners would be the least disruptive solution to the Vernon problem and the least potentially damaging to the regional economy. If legislators are uneasy about offering this option to all of California’s charter cities they could choose to narrow a piece of legislation to apply to Vernon alone, as the Assembly’s Constitutional Amendments Committee agreed to do in 1953, as Vernon is an almost unique case in California, most nearly matched only by the Los Angeles area City of Industry and Emeryville in Alameda County in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The stupidest and most risky solution is the resolution shepherded through the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors by Gloria Molina, which calls on the State Legislature to restrict city owned housing in Vernon to 10 percent of the total housing stock. As there is only one apartment building and a total of 26 homes the most likely outcome of this measure would be to open the wealthy little town to takeover attempts by grifters and con artists. There has already been one such attempt. This could guarantee that the next one succeeds. Believe me, they wouldn’t limit themselves to exorbitant salaries. The voting and high salary scandals have to be balanced against the huge infrastructural investment the people of Los Angeles County have in the Vernon industrial park and not to take a sledge hammer to the town to deal with a problem that has less drastic solutions. After years of investigation the only conviction that has emerged so far is of former mayor Leonis Malburg, for voting in Vernon while living elsewhere. The city’s replacement administrators have drastically reduced salaries, the treasurer topping out at $339,000 with the next highest at $233,000 for the city attorney. City council members make $68,000. These figures are comparable to LA senior officials. Granted LA is an infinitely larger and more important city, but Vernon’s per capita income is much higher than Los Angeles.

To put the furor in perspective, for all the Times’ fuming about a supposed hundred years of mismanagement, their proofs amounted to four $500 fines back in 1944, until we get to 2005. That says there was much that was always positive about the little industrial city, self-perpetuating leadership or not. It is not an accident that several years into the LA Times high hysterics about demon Vernon the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation voted Vernon its 2008 award as the most business friendly city in LA County with a population under 50,000. There are still 50,000 jobs that depend on how well that town functions. There are other ways to put a cap on the financial excesses of its officialdom, and even to submit them to a real electorate. But the supervisors’ notion is patently not the way.

* * *

Leslie Evans

Board member and Public Safety chair, Empowerment Congress North Area Neighborhood Development Council, a Los Angeles neighborhood council

Member and former civilian co-chair of the Los Angeles Police Department Southwest Division Community Police Advisory Board

President, Van Buren Place Community Restoration Association, in the West Adams section of Los Angeles

Webmaster for the West Adams Heritage Association

The opinions expressed are solely the author’s and do not reflect the views of the organizations, cited above, for identification purposes only.

Leslie Evans is also author of the memoir Outsider’s Reverie (Boryanabooks, 2010).

By way of disclosure:

In 1988 my wife, Jennifer Charnofsky, and I purchased a home where we have lived since on Van Buren Place in the West Adams section of Los Angeles. Researching the history of the house we discovered that it had been owned from 1922 until 1958 by the Furlong family of Vernon, first by Thomas J. Furlong, one of the three founders of Vernon, who served as Vernon city clerk from 1905 to his death in1950, when the house passed to his son Robert Furlong, who was Vernon’s mayor from 1948 to his death in 1974. Robert Furlong lived in the Van Buren Place house from 1922 until 1958. The Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission in 2000 created the Van Buren Place house Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument #678, under the name the Furlong House in honor of Thomas J. and Robert Furlong. In November 1994 Jennifer Charnofsky spoke to Leonis Malburg on the telephone as part of our research on the history of the house. Other than that neither of us has ever met or spoken to any present or former official of the city of Vernon. We have never had any financial interests, direct or indirect, that concerned Vernon.

Contact: