How Meeting Susan Anspach Completed The Circle

Goodnight moon.

Goodnight room.

Goodnight Lionel in the room.

—-Susan Anspach

By LIONEL ROLFE

I met her at a Thanksgiving party in 2012. Karen Kaye, the sister of avant garde film maker Stanton Kaye, had been throwing the parties for years at her Echo Park home. Back in 1971, Stan made a film called “Brandy in the Wilderness,” which created a large buzz among local bohemians. The bohemian scene was particularly vibrant around Los Angeles City College and a lot of us who gathered at Karen’s were the core of Hollywood bohemianism. Sometimes new faces would appear. I liked going to Karen’s parties because many of the people who went there were some of the greatest eccentrics of the era.

That’s how I met Susan Anspach.

She was as eccentric as any of us. Karen died in 2009 but her niece

Samantha kept the tradition going. Normally I’m a bit jaded when I

meet new folks, but Susan was of a different sort. When my eyes

lighted on this woman, I knew she was some kind of special lady. No

wonder I couldn’t describe her easily. I had spotted her sitting

demurely behind a dining room table and couldn’t take my eyes off

her. I couldn’t decide if she was an older biker chick or a slightly

faded apparition of a formerly grand lady. Was she in her early 40s

or early 60s? I finally determined she was an older woman who wore

her years well. I felt like I should know her name, but I didn’t. I knew

I had known her in some past life, but when? I just kept staring,

before I asked her some sort of awkward question.

“Don’t I know you from somewhere?” I asked.

Then I felt instantly embarrassed. I had clearly said the wrong thing.

She answered in a tone of voice sounding like this was a question she

got regularly and had answered many times before and she resented

having to answer it again.

I would discover that as a movie star, she had moved in more rarified

circles, so I likely had never met her. But she had been in a film that

had had a personal meaning for me. She was in “Five Easy Pieces,”

which came out in 1970. It also was one of Jack Nicholson’s breakout

film.

Susan played a pianist in the film, and my mother was a pianist. She

warned me she was not the character in the movie. “I was ebullient

and free, she was restrained, uptight,” Susan said. There had been

two female leads in the movie. One of them was Susan’s character

and then there was the character played by Karen Black, an oldfashioned

girl, a waitress, who “stood by her man” to the point of

obsequiousness. Susan was definitely more like the character she

had played than the Karen Black persona. While it may be true Susan

was not exactly like the character she played, she obviously is a

serious and intellectual person — as is the pianist in “Five Easy

Pieces.” She also said that Bob Rafelson initially offered her Karen

Black’s role, but when she read the script, she told him that it would

make a lot more sense for her to play the pianist.

In any event, I strongly related to “Five Easy Pieces,” which happened

to also be a classic of the era.

I first learned about “Five Easy Pieces” from my friend Gene Vier, a

copy editor at the Los Angeles Times and many other newspapers.

Vier was “the missing link” who knew every one. He was

immortalized by Peter Falk in the television series “Columbo,”

because Falk studied Gene’s odd mannerisms at a lunch at the Tiny

Naylors at Ventura and Laurel Canyon boulevards and got them

down perfectly for the famously eccentric Columbo.

Vier woke me up with a call about 6 a.m. “They made a movie about

you,” he told me staccato in between puffs on his ever present cigar.

Of course I was curious. Certainly he didn’t literally mean it was a

film about me.

Vier told me that Jack Nicholson had on occasion stopped by the

Xanadu, the old coffeehouse of the late ‘60s near Los Angeles City

College. “You remember him, he plays the black sheep of a prominent

musical family.” Vier knew well that my mother was the pianist

Yaltah Menuhin and my uncle was the violinist Yehudi

Menuhin.While I didn’t light out to be a wildcatter in Bakersfield, I

did work as a local newspaper reporter in places like Turlock,

Livermore and Pismo Beach. Nicholson played the role just right.

That Thanksgiving day I met Susan, I thought my faux pas with her

had ended any further conversation. But such was not the case.

Somehow we both moved out to the porch and stood talking face to

face. I quickly realized that she made me feel like I was walking on

egg shells, always about to be pounced on for saying something

wrong. I started to dance away, made nervous by the nastiness of her

retorts. But when she saw I was withdrawing, she took my hand, and

pressed it to her body, as if to say don’t go away. We migrated toward

a large couch in the front room, sat down side by side, still talking,

still holding hands. I learned then that to love Susan meant you had

to take copious daubs of love and hate.

It struck me that Susan was taking some joy in punctuating my

illusion that “Five Easy Pieces” was in any way based on me, even if

Vier had been quite accurate in seeing some strong parallels. Vier’s

comments were not meant to be literal, but the film was easy for me

to relate to personally. Nicholson, Susan told me, knew nothing about

classical music and a lot of the movie had been written

spontaneously by Nicholson as it was being filmed, although someone

else got film writing credit.

Talking about life imitating art, in real life Anspach famously had an

affair with Nicholson, who even fathered her son Caleb, and then the

two had protracted nasty and noisy and well lawyered court battles

over various.

That Thanksgiving, Susan and I became oblivious to every thing

around us as we engaged in intense conversation about most every

thing. I had been divorced for a year at that point, and was still

hopelessly in love with my ex. But talking with Susan prompted me

to make a movie in my own mind. I was, of course, the star playing

opposite her, just like Nicholson. I saw myself as Malcolm Lowry, the

hopelessly dysfunctional author who in 1939 was scribbling early

drafts of “Under The Volcano” at the Normandie Hotel near Wilshire

Boulevard. There’s a very famous story of Lowry meeting his future

and second wife Margerie at a bus stop at Western Avenue and

Hollywood Boulevard. They took one look at each other and were

suddenly hugging each other as if they were long-lost lovers from

another life. Margerie had such an influence on Lowry, it was

suggested she should have been listed as a co-author of Lowry’s great

masterpiece. This, then, was a moment straight out of literary

history and I was starring in it with Susan Anspach. You might

remember that “Under the Volcano” has been compared to “Moby

Dick.”

Somehow, at that moment, Susan made me feel like that bumbling

figure of a great author, ready for the right woman to come along and

save him.

Of course Susan was never likely to play second fiddle in my

orchestra. She was in many films, the greatest and best known ones

out of the ‘70s and ‘80s. One of them was in Woody Allen’s “Play It

Again Sam.” Once as were watching “Running” with Michael Douglas

as a would be long distance runner trying to go to the Olympics, she

burst into intense tears. At a critical point, Douglas stumbles and

falls and has to be carted off by paramedics. Susan played his ex-,

who still was lovingly standing by him, even if her husband’s

obsession had destroyed their marriage. Michael had so insisted on

verisimilitude, he did exactly what his character did, and took a

painful fall, and then got back up and pushed himself across the

finishing line. The pain you saw on his face was real.

Anspach is proudly political. Her children stood with her on Wilshire

Boulevard, Los Angeles’ grand concourse, holding signs for Cesar

Chavez, with whom she later marched and fasted and who also gave

her a much treasured cross. The signs were taller than her children.

She cried when Obama won. “We fought so hard in the ‘60s for civil

rights.” She remembered the time she and Billy Dee Williams who

were both starring in Broadway plays at that moment, were were

turned away from a restaurant in New York City because Williams

was black. And although she was adamant that “something is rotten

in USA,” she asked me if I thought Clinton could win. “Imagine! If I’m

still alive, I’d live to see a black man and a woman become presidents.

Wow!”

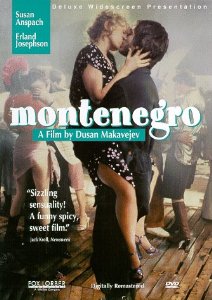

Of all the films she showed me, her masterpiece may have been the

film “Montenegro,” a 1981 black comedy by Yugoslav director Dušan

Makavejev shot in Sweden with actors from some of Bergman

masterpieces. In Montenegro, Susan plays a bored blond housewife

from America living with her very boring Swedish husband. She is

kidnapped by Gypsies and only sort of tries to escape. Susan said she

saw her character very much as a kind of Marilyn Monroe. As a

young drama student in New York, Susan joined other important

actors like Dustin Hoffman and Marilyn Monroe in being trained by

Lee Strasberg.

Susan had thought long and hard about Marilyn Monroe. Over the

year or more our friendship lasted, we often talked about what made

Monroe tick. Susan had an interesting take on Monroe’s marriage to

the great playwright Arthur Miller. She said not to be so hard on

Miller because he was hardly able to write a word all the time he was

married to her.

Susan also pointed to Monroe’s manner of looking half sleepy all the

time. It was no accident, she proclaimed. Look at her eyes, she said.

They always looked like they were partly closed. She looked like a

person always wanting to get into bed. She wasn’t tired so much as

just sorta of sleepy. It was as if she were in a perpetual state of

getting ready to be played with in bed, she said.

Before leaving New York to come to Hollywood, Susan made her

mark on Broadway—she played the lead in the original “Hair.”

Broadway was also where she met her lifelong friend Dustin

Hoffman, also a Broadway actor.

Susan now feels a bit slighted by Hoffman, whose career is churning

along well enough. There was a lot of emotion there. When we were

later trying to work out the logistics of meeting up one day, I

suggested Canter’s in the Fairfax District. Canter’s had been a

central meeting place in Los Angeles since at least the ‘60s. Susan

strongly nixed that as a destination. With emotion in her voice, she

said that she used to meet up with Hoffman at Canters, and with her

husband and kids. She did not want to rekindle memories.

So we didn’t meet at Canter’s. We carried on this way for more than a

year and then it all came to an end for various reasons. But for many

weekends, I looked forward to going to her place and watching

movies and talking until late at night. Running into Susan Anspach

that Thanksgiving day connected different periods of my own life.

*

Lionel Rolfe is the author of a number of books including “Literary

L.A.,” “The Menuhins: A Family Odyssey,” “Fat Man on the Left” and

“The Uncommon Friendship of Yaltah Menuhin and Willa Cather.”

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.