Honey travels through portals of time

Introduction to the portals

Figure 1: Toypurina mural, Ramona Garden

The people who lived in Los Angeles when it was part of the Spanish empire and during the years Mexico governed it often appear in history books as two-dimensional: cardboard men in sombreros riding pretend horses fitted with painted silver decorated saddles and paper cut out dark eyed women with high combs that lift masses of hair veiled with lace mantillas. They speak pure Castilian Spanish.

This is a cartoon image of the Pastoral Era after secularization of the missions, largely inspired by a “boomer” subsidized by Southern Pacific Railroad to increase the number of passengers on trains to Los Angeles.

The forty-four people that walked from the Mission San Gabriel in 1781 are silent.

They were small people. The average male was 5’2” tall. The average height of the soldiers was 5’6” – the soldiers must have towered over the little people from Sionola and Sonora. The settlers were descendants of Africans and Mexican Indians, two Spanish men, and mixtures of what is referred to as races now but the Spanish had “castas.” The man that came from the Philippines and his daughter did not make it. They were quarantined with small pox in Baja California. His casta was “Chino.” The Indians among them may still have spoken a Uto-Aztecan language.

The ancestors of the small people had suffered from European diseases and many of them had died and many may have died during the period when Spain enslaved them and worked them to death.

If they hadn’t been poor, the first Spanish Colonial people to settle Los Angeles would not have left their extended families behind. If they were not desperate, they would not have traveled to a place that must have been the equivalent of another planet to live forever.

I imagine them, though. I imagine they woke from the shelter of the reed huts the local Indians helped them build in the morning and walked downhill to the edge of the river and listened to all the birdsong and the rush of clear water through the Narrows. The children built the dam for irrigation as if it were a game. Children just about always find a way to play a game. Egrets cast moving black shadows over the flowing green water.

The native people that preceded the real Spanish Colonial families are shadows that whisper. Scotland-born Hugo Reid – thirty years before he became the fictional character Ian McPhail in Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel Ramona – gathered those whispers for the first influx of Americans after 1853 and wrote them in letters to the Los Angeles Star.

By then, most of the Indians were de facto and de jure slaves. Probably all of the native people were illiterate. [1] No one like Frederick Douglass[2] or Solomon Northrup[3] emerged from Indian slavery to write about his life.

Most of the earliest Spanish Colonial settlers were illiterate. The first school taught by Luciano Valdez lasted from 1726 to 1731. The longest span of continuous instruction was at the school held in the home of Don Ygnacio Coronel, on “la plaza” during the years 1838 to 1844, during the Mexican era. The Catholic priests were literate but they rarely came “to town.” Vicente Feliz — the first Comisionado — was literate. Settlers from Mexico during the Mexican era were often literate. All the governors were literate.

The quotidian Colonial writing had to do with fanegas of wheat or a resolution that the adobe houses should be whitewashed — or it was scandalous writing: a report of a poblador that committed adultery with a native woman or two men that were useless and had to be returned to Mexico – or the writing was about political intrigues and opéra bouffe tempests obscure to us now but that once had significance. The city’s 1836 resolution to remove the Indians from Yang-Na was critically important, set out in simple language and kept in the municipal archives. This is how come no one seems to know where Yang-Na was – because of that ordinary writing.

A few gifted writers visited Los Angeles – Friar Crespi and Friar Font were two of them. August Duhaut-Cilly, who visited Los Angeles in 1827, Richard Henry Dana (1840) and Edwin Bryant (1847) wrote about what they saw in Los Angeles.

In 1877, historian Hubert Howe Bancroft sent Thomas Savage to Los Angeles to interview some of those people that had lived in Mexican-era Los Angeles, among those interviewed was Antonio Franco Coronel, whose stories are told again in Tales of Mexican California.[4]

The stories Antonio F. Coronel told Helen Hunt Jackson in his palatial adobe that stood about where the Greyhound station is today filled the background of her novel Ramona (1885).

Leo Carrillo (1890-1961), a descendant of Captain Jose Antonio Ezequiel Carrillo (1796-1862), was born in an apartment in The Baker Block on the southeast corner of Main and Arcadia Streets, built in 1877. His “Tia Arcadia” was married to Abel Stearns. Stearns was part of the “Mexican” oligarchy that ruled Los Angeles – at least, as much as anyone could rule such an anarchistic population. After Stearns’ death, Arcadia married Col. Baker, and they established The Baker Block on the site of Stearns’ El Palacio. Baker Street, the street that led into the original settlement and that was once part of Toma Street, is named after the Col. Baker, Leo Carrillo’s “Tio” through marriage. Everyone was related one way or another in early Los Angeles, even the Indians. The settlers sometimes married Indians.

After Leo’s father injured his foot, the family moved to Santa Monica, and everyone in the Carrillo family big enough to fish fished. They ate a lot of corn tortillas and fish.

Baker and Arcadia Bandini de Stearns de Baker founded the City of Santa Monica with Senator John P. Jones of Nevada. An incident took place at their elegant Hotel Arcadia that shocked the city.

Figure 2: Hotel Arcadia

Griffith J. Griffith was a pompous man. Harry Carr, a Los Angeles Times reporter, wrote, “He had a strut, a gold headed cane, a flower in his buttonhole and a patronizing little snicker. He was married to Mary Agnes Christina Mesmer, a descendant of the Verdugo family. He had donated 3,015 acres of Rancho Los Feliz to the City.

On September 3, 1903, in Suite 104-5 of the Arcadia Hotel, Griffith’s wife was packing to return to their home in Los Feliz. Griffith went downstairs to the bar and drank absinthe. He came back upstairs and shot his wife in the face.

She staggered to her feet and threw herself out of the window. She survived. After his return from his stay on Alcatraz, Mrs. Griffith forgave him and was at his side when he died.

In The California I Love,[5] Leo Carrillo – best known for the role he played as “Pancho” on the 1950s television series “The Cisco Kid” — wrote a collection of stories. Some of the stories are drawn from his childhood memories. The remainder of the stories consists of family legends about Los Angeles history. The family legends are about Mexican-era Los Angeles.

Leo Carrillo was the troubadour of the era of banquets with chili in every dish, the dances, and the love stories. He was a descendant of Antonio Carrillo, who built what was probably the first adobe near “la plaza.”

An opaque glimpse of the lives of the people that lived in Los Angeles before the American military arrived in 1847 may be seen through the portals of today’s streets, places, murals, and monuments.

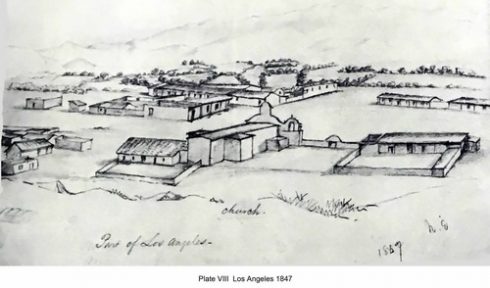

The first photograph of Los Angeles was not until sometime after the city rebuilt after the 1862 Great Flood that devastated California’ and left the Central Valley under water. The watercolors William Rich Hutton created when he was working on the first survey and Charles Koppel’s 1853 lithograph let us see what the city looked like, and there are maps that allow us to guess where buildings stood and roads ran. The maps and watercolor paintings are in the public and private libraries in and near Los Angeles. The photographs may be seen in the on-line photograph collection at Lapl.org.

Below is a list of portals.

List of spaces, monuments, etc.

Los Angeles River Center and Gardens is located near the confluence of the Los Angeles River and the Arroyo Seco. The Visitor Center self-guided exhibit describes the history of the Los Angeles River, its current status, and a vision for the River’s future. Spanish Colonial inland communities were built close to rivers, as was Los Angeles. The river provided the vecinos with water for domestic use and for agricultural irrigation.

Figure 3: 1895, Irrigation Ditch, Los Angeles River. Courtesy Los angeles Public Library

Channel Islands National Park: Archeologists recovered artifacts characteristic of ancient Paleo-coastal sites that were occupied between 8,000 to 13,000 years ago under the Main Ranch House, which is part of the historic Vail & Vicker Ranch at Bechers Bay on Santa Rosa Island. Santa Rosa Island is also the location of Arlington Man, the oldest known human remains found in North America, dating to about 13,000 years ago.

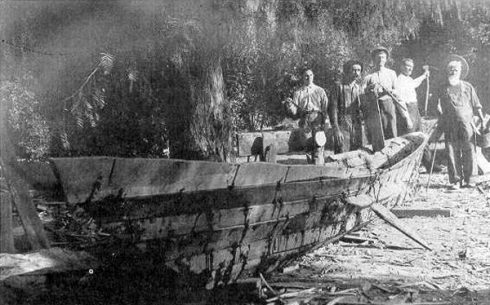

The coastal Tongva were boat builders. The boat they called the tomol was a plank boat, also called til’at by the Tongva. Bernice Eastman Johnston described how people without metal tools built plank boats.[6] [7]

The Tongva also used dugouts, and reeds tightly bound together and calked with tar.[8] These were sea-worthy and reached the Channel Islands.[9]

Archeological evidence so far supports a conclusion the plank canoes were used for only 1,000 to 2,000 years BP (Before Present). Human beings occupied the Channel Islands by about 13,000 years ago.[10] [11] Presumably, the Southern California Indians used dugouts and reed boats before they invented (or were introduced to) the plank canoes. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4: Plank Canoe, Bowers Collection

Tongva Park is near the Santa Monica pier. The park is named after the indigenous Tongva people that lived along the coast.

Many of the people today called the Tongva were called the Gabrieleño during the Spanish Colonial era after the founding of the Mission San Gabriel. The native people recruited to the San Fernando Mission were called Fernandeño.[12] [13]

Inasmuch as the first people arrived before the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, it is unlikely that we will ever recover archeological evidence that may lie underwater on the coast of Los Angeles and around the Channel Islands. Also, Los Angeles is built on top of areas of early occupation. Our roads are sometimes built on top of ancient Indian roads.

Indians may have been in Los Angeles for longer than 15,000 years. The Tongva, however, are descendants of Uto-Aztecan-speaking peoples from Nevada into Southern California about 3,500 years ago.[14] They superseded or absorbed a Hokan-speaking people.[15]

The current estimate of the native population in pre-contact Alta California is 310,000.[16] The native population in the Los Angeles area is estimated at 5,000. Both figures may only be seen as guesses because contact with European diseases killed nine out of ten of the native people.

Ancient trade roads connected the native villages in the Los Angeles basin with each other and with the villages in San Diego, the Mohave, the Chumash along the coast, the Central Valley Indians and the Indians living near today’s Lake Merritt in Oakland.[17]

The Gaspar de Portola expedition went from San Diego to Los Angeles in the summer of 1769, traveling on Indian roads.[18] On August 2, 1769, the expedition set out from their campsite somewhere west of Alhambra on what Portola called “a good road.”

Portola crossed the Los Angeles River on August 3, 1769, at about where today’s Broadway Bridge is. This is likely also the route followed by the Anza expedition, which took settlers to San Francisco in 1776. Anza wrote in his diary that they followed “the regular road to Monte Rey.”

Portola met with people from the large village of Yang-Na “on the road” about 1.25 miles from the location where they had crossed the river. Scholars disagree about the location of Yang-Na. James D. Hart, for example, wrote in his A Companion to California:

“Yang-Na: Indian village once located on the site of downtown Los Angeles, in present Elysian Park.”[19]

Possibly there was a small Indian village in Elysian Park, but that village, if it existed, was not the large trading village of Yang-Na. Besides, downtown Los Angeles is not in present Elysian Park.

Other scholars assumed Yang-Na existed next to the Vignes winery. Rancho de Poblanos — was a little south of the Vignes winery. After the city’s 1836 eviction of the remnant population of Yang-Na, the native people were removed to Rancho de Poblanos.[20]

Some historians allege Yang-Na was on the grounds of the Vignes winery, called El Aliso – named after the giant sycamore that had grown for about 400 years on what became the winery .

Eastman located Yang-Na at a spot “near Union Station in Los Angeles.”[21] Casa de Lugo was built in 1836, the time of the eviction of Yang-Na, at approximately the parking lot in front of Union Station. This house became part of Old Chinatown.

Archeological artifacts unearthed so far suggest pre-Spanish human occupation of the area from today’s MTA building to City Hall, for a period of 3,000 years, and this includes the Union Station area.

The Spanish-surnamed occupants of Los Angeles inherited the Indian roads.

The native village structures were made of plant materials. All of California famously suffered from flea infestation through the nineteenth century, and the native people fairly frequently burned their huts to remove fleas. The site of the Indian village could have changed – probably changed – over 3,000 plus years; nonetheless, Yang-Na and predecessor village would have been quite near the roads, and the roads all led to today’s plaza area.

The village pre-contact occupied quite a large area, not including the gathering fields surrounding Yang-Na or the playing fields or the menstruation huts. Until 1836, the remnant village – after many Indians died of agriculture-related diseases and after many were forcibly conscripted to live and to work in the missions – was in the area of today’s El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument.

La Brea Tar Pits is a tautological place name. “Brea” in Spanish means tar. The Portola expedition passed the tar pits – natural asphalt that seeped from the ground — in August 1769. Pleistocene mammoth fossils are among the fossils of the animals from the last Ice Age immured in the tar. The mammoths may have created the Calle de los Indios route. The Paleo-Indians likely followed the giant animals’ road to Santa Monica and from there to the Channel Islands – or the other way around, if the Paleo-Indians first settled on the Channel Islands; at the end of the last Ice Age, the Channel Islands were only five miles from the mainland.

Figure 5: La Brea Tar Pits animals

Serra Springs: The Portola expedition camped near the pair of springs now located on the campus of University High School on August 3, 1769, after crossing the Los Angeles River. The Tongva called the springs Kuruvungna, and their village was Kuruvunga. California Historical Landmark # 522.

Wilshire Boulevard follows the route that the Portola expedition took in 1769. This was the third branch of the El Camino Viejo that went from the present plaza area. This branch led to Santa Monica past the tar pits. This road was a branch of the Indian road later referred to as “El Camino Viejo,” and the name of the branch was Calle de los Indios.

Leo Carrillo wrote in The California I Love:

“Much of the romance of ranchera life seemed to center around those great grants near the ocean. …This was the era of the mighty clipper ships from Boston, which brought every kind of luxury imaginable to appeal to the taste of the Californianos.[22] ….

“The great ranchos of which I speak funneled their owners, their families, the native Indians and visitors down a ‘highway’ known then as Calle de los Indios. Later this became as La Brea Way and still later as Wilshire Boulevard.

“Down the Calle de los Indios went the carretas, those two-wheeled awkward ox-drawn carts which formed the only wheel transportation in California. Their noise was almost paralyzing.” [23]

Figure 6: Ox cart

Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Highland Park on the eastern side of the Los Angeles River. One of the collections in the Southwest Museum is American Indians of California. Charles Fletcher Lummis gained the support of city leaders and opened the museum in 1907. The museum moved from Downtown location to its current location in 1914. The Autry Museum in Griffith Park (Griffith Park comprises a large portion of the former Feliz Rancho) absorbed collections from the Southwest Museum in 2003. The Autry’s collections include basketry in the Southern half of California, and that collection includes Tongva baskets.[24]

Images of Toypurina

In East Los Angeles, a 60-by-20 foot mural in Boyle Heights is painted on the main wall of Ramona Gardens, a public housing complex.

A little west of El Monte, at the Baldwin Park Metrolink Station is a 20-foot arch and a 100-foot plaza. A stone mound within the installation is designed as a place of prayer, and is meant as a tribute to Toypurina.[25]

Toypurina was nine years old when the Portola expedition arrived in Los Angeles. In 1785, she was one of the participants in an Indian revolt against the mission and its forced conscription of the Tongva people.

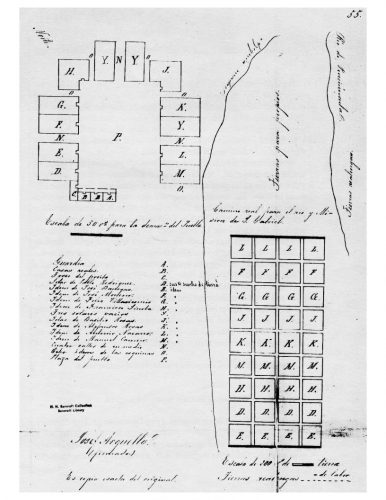

Broadway Bridge: Today’s bridge spans the fording place of the 1769 Portola expedition and probably the place the expedition crossed on the return trip in January 1770. This span (not the bridge, the river where it runs under the bridge) was the “camino real” marked on the 1786 Arguello map of the first village. (Fig. 7 )

Figure 7: 1786 Arguello Map

The first Spanish Colonial explorers’ campsite

A metal plaque fixed to rocks near Elysian Park Drive on North Broadway near the Broadway Bridge reads:

“NO. 655 PORTOLÁ TRAIL CAMPSITE (I) – Spanish colonization of California began in 1769 with the expedition of Don Gaspar de Portolá from Mexico, then still Nueva Espana. With Captain Don Fernando Rivera y Moncada, Lieutenant Don Pedro Fages, Sgt. José Francisco Ortega, and Fathers Juan Crespí and Francisco Gómez, he and his party camped near this spot on August 2, 1769, en route to Monterey.”

On August 2, 1769, the Portolá expedition camped on the eastern bank of the Los Angeles River, at about what is today the Downey Recreation Center. On August 3, 1769, the expedition crossed the Los Angeles River for the first time.[26] The marker should be on the other side of the river.

Los Angeles State Historic Park is on the site of the Southern Pacific Railyard (1876). This has been popularly called “the cornfield” for a long time. One story is that corn syrup fell off the freight trains. Another is that corn kernels fell off the freight trains and grew into corn between the tracks.

The cornfield is in the location of the first suertes or agricultural fields dug from Yang-Na’s gathering fields in 1781. Later fields were dug from the path of the river below the toma and alongside the first village in the land designated as “tierra para propios” on the Arguello map.

The cornfield may have been called the cornfield because it was a cornfield.

If you stand on North Spring near Nick’s café and look across the cornfield you should see the land is below the terrace carved by North Broadway before it reaches the bridge. A necklace of terraced hill partially circled the base of the Elysian Park hills before the city cut a road over it in the late 19th century.

North Main (More likely North Spring) through Dogtown: This is the approximate route that the Portola expedition took after they crossed the Los Angeles River on their way to Yang-Na and from there to Santa Monica. This was Toma Street, more or less. Toma Street blurred into Alameda near the plaza. The portion closest to the river and closest to the first village may be what is today Baker Street.

Today’s Baker Street seems to have been a segment of land on the map of the “Land to be conveyed by Arcadia de Baker to the SPRR Co.” on the Huntington digital library.

Figure 8: Huntington digital archives: Land to Be Conveyed

The date on the map – 1882 – is probably wrong. Arcadia married Stearns in 1841 when she was 14 and lived to 1912 but the railway’s river station was established in1876.

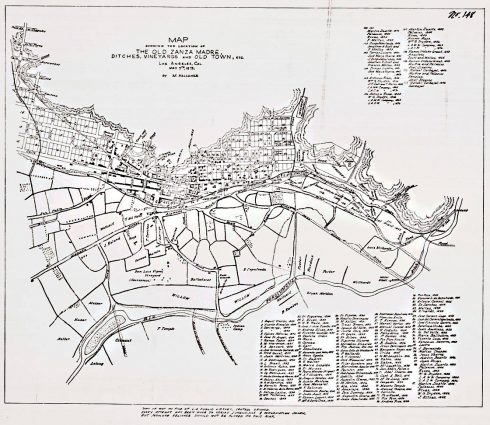

On the other hand, City Engineer M. Kelleher’s map of Los Angeles – drawn in 1875 — does not show the Baker tract at all.

Figure 9: M. Kelleher’s 1875 map of Los Angeles showing the location of the old Zanja Madre ditches, ineyards, and Old Town

It’s possible the Kelleher map was a reconstruction of a time before Col. Baker acquired the tract.

The Kelleher map may be better explored by going to the Huntington digital website: http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15150coll4/id/11850/rec/4. (Retrieved /17/2018).

The Kelleher map shows an unnamed “Road” leading to another unnamed “Road” – the “Camino Real” – marked on the 1786 map, the place where the Portola expedition crossed the river in 1769 and (most likely) again in January 1770, to the Zanja Madre (the thick line around the base of a terrace of the Elysian Park hill). The first road on the Kelleher map that went along the western side of the Carbajal Grant (dated 1843, although no grants were confirmed until 1853) was not near the river as it was in whatever time is depicted in the map.

Comparing the two maps, it looks like Baker Street could have been the top portion of Toma Street.

The Kelleher map clears up the question of the role played by the toma. It looks as if the toma was a dam but the intake from the river was higher up along the river; that is, there was a fairly wide irrigation ditch with the mark “D.Ech” and the water pooled at “Toma” before leading to the Zanja Madre.

Also, Toma Street continued past the Ramon Orduno Grant, land marked Abel Stearns on the map — with the Stearns Mill indicated by a little rectangle above the Zanja Madre to Calle Principal.

Toma Street, by the time of “Land to be conveyed by Arcadia de Baker (Arcadia Bandini de Stearns de Baker)” was San Fernando Street. San Fernando Street was later called “Upper Main.”

Toma Street may have been re-named San Fernando Street because it once led to the road that crossed the river, and from there went towards the San Fernando Mission. A road – not shown on either map – did lead towards the San Fernando Mission on the eastern side of the river.

Toma Street/San Fernando Street/Upper Main was probably what is today North Spring, not North Main. Arroyo Seco Street on the Kelleher map is likely today’s North Main. Arroyo Seco also emerged at the plaza area. It cut through the Luis Wilhardt tract and crossed the river a distance from the original crossing to a second crossing.

Historic Marker No. 161 marks the site of “Mission Vieja,” the 1771 structure located and then abandoned for the present site of the San Gabriel Mission.[27]

Metro Gold Line Shops and Yard at 1800 Baker Street. Abel Stearns either built or acquired the Stearns’ Mill in 1834. Reconstructed in brick in 1860, it is now Capitol Milling at the edge of Chinatown. Stearns’ widow, Arcadia Bandini de Stearns de Baker, transferred this portion of the land in the area of the former suertes to Southern Pacific Railway in 1875, which is why the street is called Baker Street.

The area of the Metro Gold Line Shops and Yard is rather small to have accommodated the first Spanish Colonial village in 1781, but two things happened to reduce the land area: the river was broadened here to make a more uniform concrete bed in the 1930s; and a flood brought down part of the hill in the 1930s.

Nonetheless, the first Spanish Colonial village in Los Angeles occupied this area. It’s not public. You can walk up to the guard’s house, which is at about the location of the 1781 guardhouse, at today’s 1899 Baker Street.

Figure 10: Google map of 1899 Baker Street

Biddy Mason timeline wall

Only one place in downtown Los Angeles shows a copy of the 1786 Arguello map of the place that L.A. began: the wall in Biddy Mason Park. You can reach the wall by going through the Bradbury Building, parts of which were background for the first Blade Runner film.

Los Angeles Public Library Central Branch mural

The Los Angeles Public Library Central Branch Rotunda mural by Dean Cornwell: “The Founding of the Pueblo de Los Angeles” is a panorama with an elaborately cloaked priest, a Spaniard reading a document, several other Spaniards, the rear end of a donkey, flags, a man playing a small guitar, sheep, two naked babies, ducks, and several other priests praying intently. Everyone looks white, although one of the babies and his mother has dark hair. There is a very white naked old man. This mural renders in paint Charles Dwight Willard’s theory about how Los Angeles was founded.[28]

“It is no easy task to winnow the records of a vanished people. The Gabrielinos, like so many tribes who owe their extermination to the whites, had few champions among the new settlers.”[29]

Charles Dwight Willard, a Los Angeles “booster,”[30] embroidered and inflated Guinn’s conclusions in The Herald’s History of Los Angeles (Kingley-Barnes & Neuncer Co., Publishers, 1901). Southern Pacific Railroad subsidized local chambers of commerce to hire “boosters” to stimulate population and economic growth, which in turn increased the railroad’s land sales, and its freight and passenger traffic.[31]

Diorama of the founding of Los Angeles in the “Becoming L.A.” exhibit in the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum

Joseph Leland Roop’s diorama of the 1781 founding of Los Angeles, constructed in 1931 and located at the Natural History Museum, in the “Becoming L.A.” permanent exhibit shows a Native American man beginning the construction of the first home, the primary structure built of sticks. It also shows three “leather jackets” – soldiers on horseback – two mules laden with sacks, and 43 people in various colors, four obviously African, a woman that looks white, and the others brown-skinned. The ethnic composition, the clothing of the soldiers and settlers, and the native man helping build the first brush hut for the settlers corresponds to the information we have now about the settlers.

The place where the pueblo began is portrayed in the diorama as sere, a desert studded with small cactus plants. The landscape was not a desert in 1781.

The Roop diorama creates a soft, diffuse and mysterious painting as background for the first settlement. There is no clue in the work about where Los Angeles began.

The landscape of the Los Angeles basin in the background of the Roop diorama is beneath the settlers; that is, they are shown walking on a hill where the first stick and willow house is built, a significantly elevated hill. The river meanders peacefully in the distance. Riparian trees embroider its eastern banks.

This is the only public monument showing the Indian presence in the City of Los Angeles. At the San Juan Capistrano Mission, a statue of Father Serra with an Indian boy stands. El Molino Viejo in San Marino, built in 1816 under the direction of Father Zalvidea of the San Gabriel Mission –built by Indian labor – was a gristmill. It contains a small display of Indians working in the gristmill.

La Placita is the popular name for La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, the Catholic Church facing the plaza. The name “La Placita” may have been a reference to the little plaza next to the church. The church is part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument.

The pueblo’s first church foundation was laid in 1814. No one knows where the first church foundation was except that it was near the river and that the foundation was endangered by the change in the western bank of the river after the 1815 flood. It was probably built somewhere in the agregado, the district that developed after 1790 near the river on the road from the original village to Yang-Na — so more or less near today’s concrete channeled river at the top of either today’s North Spring Street or North Main Street on the western side of the river.

In 1818, Governor Sola directed that the first church be built in its present location – rather peculiarly, over the pueblo’s trash pit. Joseph Carpenter completed the church with Indian labor in 1822. La Placita was rebuilt after the 1862 mega-flood that swamped most of California.

El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument

El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument surrounds today’s circular plaza. Spring, Macy, Alameda and Arcadia streets, and West Cesar Chavez Avenue (formerly Sunset. Part of this street – between Alameda and Pleasant Avenue— now part of Cesar Chavez Avenue, was formerly called Macy Street) are the park’s boundary streets. The district was designated as a state monument in 1953.

The plaza — sometimes referred to as the Old Plaza: A plaque set in the sidewalk on Main Street indicates the plaza was laid out between 1825 and 1830. It is unlikely – and probably impossible – for the plaza to have been laid out between 1825 and 1830.

A stylized cross near the Pico house reads “EL PUEBLO DE NUESTRA SENORA LA REINA DE LOS ANGELES FELIPE DE NEVE SEPTEMBER FOURTH 1781.” September 4 was an administrative date. Two groups of pobladores arrived at the site for the first village beginning in June 1781.

The area of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument was within the “Four Leagues Square” of the Spanish Colonial pueblo, but that was a very large expanse of land. The term “pueblo” meant the village — its structures surrounding a central rectangular plaza – and its fields and pastures. The wording on the cross, however, suggests that the village was located around the present plaza because most people think of a pueblo as the village.

In 1781, the area encompassed by El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, the Casa de Lugo (the front area of Union Station), over to El Aliso and as far west as City Hall was occupied by a large Native American trading village, through which roads led up to the site of the original pueblo and from there to the Mojave, over the Tehachapi Mountains into the Central Valley, to the Cahuenga Pass, and to San Pedro.

The Los Angeles municipal archives, now stored in the Piper Tech building behind Union Station across the street from a Denny’s, contains an 1847 plan for the plaza to be turned into a square.[32] The plaza did not become a square until the 1870s.

The E.O.C. Ord/William Rich Hutton survey of August 3, 1849, however, shows a collection of structures around a larger empty area, irregular in shape.

Figure 11: Detail from E.O.C. Ord’s first map of the City of Los Angeles, August 29, 1849.

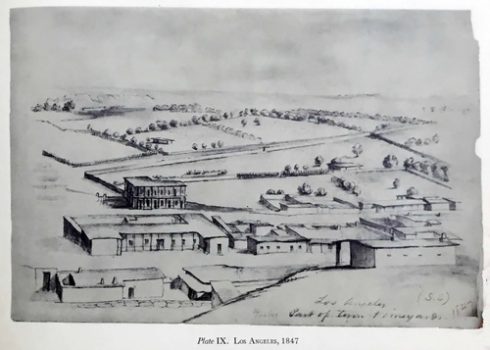

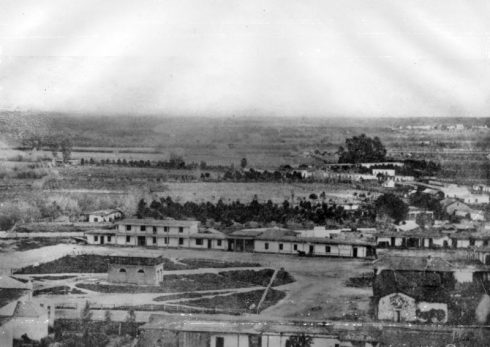

William Rich Hutton’s sketches, beginning in 1847, confirm that the plaza was a large, irregular open space.

Figure 12: William Rich Hutton, 1847, Plate 8 from California: 1847-1852, Drawings By William Rich Hutton (The Huntington Library, 1956).

Figure 13: William Rich Hutton, 1847, Plate 9 from California: 1847-1852, Drawings By William Rich Hutton (The Huntington Library, 1956).

The Charles Koppel Lithograph of 1853 also shows a large irregular open space.

Figure 14: Charles Koppel lithograph, 1853.

“The plaza” as late as 1853 could not have been laid out or established as anything similar to the Spanish Colonial rectangle. It does not appear from these images to have been designed; rather, the open space simply was called “the plaza.”

By the 1870s, “the plaza” looked square or almost square.

A map of the area drawn March 12, 1873, by A.G. Ruxton[33] shows that by 1873, the plaza was a shape that is more like a square. The 1857 Dryden reservoir, a brick structure, was more or less in the center of the plaza.

Figure 15: March 12, 1873, map of the plaza area by A. G. Ruxton.

Along an eastern side Marchessault Street ran according to the Ruxton map. Later, after railroad tracks ran through Alameda (about 1876), Marchessault continued (not on the map) across to the area marked on this map as “Road.”

The rectangle marked on the Ruxton map “Wilson” was property owned by Don Benito Wilson. The Wilson property is now occupied by the parking lot for the Terminal Annex.

Wine Street (on the Ruxton map) became Olvera Street in 1876. Off Wine Street was a long block for the Francisco Avila Adobe House, which is smaller now. Christine Sterling successfully advocated for the creation of the Olvera Street marketplace, completed in 1936.\

Figure 16: Detail from Ruxton map, showing Marchessault and Wine Streets. The Wilson property is just below the word Alameda at the bottom of the map.

Sterling began her advocacy for Olvera Street with her concern over the fact that the Avila adobe was about to be demolished. It is a part of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historic Monument.

The National Park Service date for the Avila adobe is 1818,[34] but that is unlikely. According to H. H. Bancroft’s list of the 99 pobladores compiled by alcalde Cota, Francisco Avila, as of February 1818, owned no land. He made two petitions for a grant of land, each of which was unsuccessful, until he was granted the Rancho Las Cienegas in 1823. He made the rancho into a success after a few years. Local historian J. M. Guinn searched the municipal records – beginning in the 1880s. The records before the late 1820s are lost, and there were no recorded deeds before the American era, but he concluded there were four adobes in the area of the plaza before 1828. He did not list the Avila adobe.

Calle Principal on the Ruxton map — later called Main Street — was a broad Street that ran below the Pio Pico house to a cemetery that partly surrounded one side of the plaza, marked “1822,” the year the church was completed. The Church Plaza was behind the church, and an area marked “Gardens” was below the Padre’s House. “House of Pico” adobe – Pio Pico’s personal house — was next to the cemetery.

The Pico House – the hotel structure still in the historic district – is marked on the A. G. Ruxton map as completed in 1869, acquired in 1856. Jose Antonio Carrillo’s adobe was demolished for the Pico House. The Carrillo adobe was constructed between 1822 and 1825. There is no record of an earlier house in the area of the plaza.

The notorious Calle de los Negros, usually referred to by Americans as “Nigger Alley,” ran below an area marked “Street” below the plaza on the Ruxton map.

On the Ruxton map, the Vicente Lugo house property is marked 1855, but other sources indicate it was constructed in 1836. The date on the map could mean the date the property was recorded. The Casa de Lugo became St. Vincent’s College and later became a part of Old Chinatown. It was demolished for the construction of Union Station in the 1930s.

The earliest-known photograph of Los Angeles is undated but there is no Pico House, so it was taken before 1869. The reservoir stands in the plaza, so it was taken after 1857, and very likely after the 1862 flood. In the photograph, the almost square shape looks like a rectangle. The very large tree in the background is El Aliso, which stood in the courtyard of the Vignes winery. Luis Vignes named the winery “El Aliso.”

Figure 17: Earliest-known photo of Los Angeles, undated but taken between 1857 and 1869.

On the Ruxton map the two-story Casa de Lugo stood almost directly opposite the church, on the other side of the plaza.

The streets were evidently dirt in the photograph. There were no streetlights.

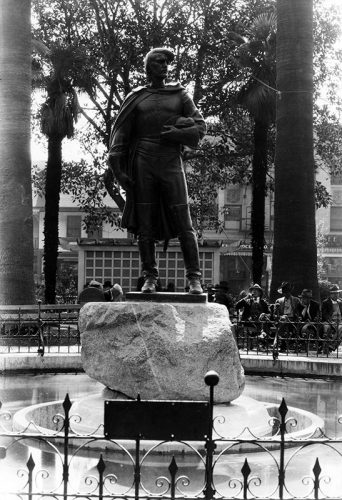

Statue of Felipe de Neve

A statute of Felipe de Neve (1724–1784) stands on a rock near a bench in the plaza. The face of the statue is soap star handsome. He wears thigh-high boots, leather gloves and a cape. Governor Neve founded Los Angeles. He chose the location in 1777 on his way from Loreto, Baja California, to Monterey.[35]

Figure 18: Felipe de Neve, photo from 1930, courtesy LAPL.

El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument was not the birthplace of L.A. That is, it is not the site of the first village laid out by Felipe de Neve in Los Angeles in 1777, on his journey from Loreto in Baja California to Monterey, the village established in 1781.[36]

Statue of Father Serra

A statue of Father Junipero Serra, the founder of the California mission system, stands on a concrete pedestal on the east side of the plaza. The statue holds a cross high in his right hand and he cradles a toy-sized mission in his left.

Father Serra strongly opposed the establishment of civilian pueblos. “Missions are what this country needs,” he said.[37] He may have spent one night in Los Angeles, however, soon after the original village was established.[38]

The San Gabriel Mission, however, was where Neve stayed in 1781 to write his instructions for the two pueblos he created in Alta California: San Jose, founded in 1777, and Los Angeles.[39] The first settlers in Los Angeles stayed near the San Gabriel Mission before they walked in two groups, the first group arriving in June 1781.

The first location of the mission, founded in 1771, was near what is now the intersection of San Gabriel Boulevard and Lincoln Avenue. The church relocated to the present site in 1776.

Old Chinatown was demolished to clear land for Union Station. A boundary of Old Chinatown is in the Rest Area at 700 North Alameda, designated by a line of bricks. This area was about where Casa Lugo stood and was part of Yang-Na before the arrival of the Spanish.

Today, Aztec fire dancers wearing yellow, blue, green and indigo and sometimes orange feather headdresses stomp to the percussion of drums in the plaza in front of the old Catholic church building downtown. Not far away – across the street near the plaza — fruit vendors cut up pineapples and melons to put in clear plastic cups. A hat seller brands the buyer’s name on a hatband with a Versa tip. Elderly women wearing thick-heeled shoes dance somberly with their husbands to a song that sounds sung in Spanish by a man with gold teeth. Tourists walk through Olvera Street looking at leather sandals and etched leather handbags. Mariachi players in black wearing stylish sombreros and strumming guitars walk as slowly as lions. The colorful Aztec fire dancers that perform in the plaza have a connection to the history of the plaza. The Spanish Colonial concept of the plaza as a religious space was a meld of European and Mesoamerican use of public space.

Grumprecht, in The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death and Possible Rebirth, described the native homes as dome-shaped shelters. “Tule matting, grass, or brush was then attached to form walls, sometimes a half-foot thick. The doorway and the floor were also typically covered with mats made from tules. The homes of each village were centered around a small, unroofed religious structure known as a yovaar, which was also built of willow. Circular and about three feet high, it was made of thin willow branches intertwined like the walls of a basket.[40]

Hugo Reid called the unroofed brush-walled enclosure the “church.”[41] By 1850, there was no standing “church” (Indian spiritual enclosure) remaining in Los Angeles.

The Laws of the Indies recommended a location for inland Colonial pueblos at a distance from Indian communities. The practice, however, in Mesoamerica had been to meld existing plazas with Spanish planning ideals to pacify indigenous people.

The commonly accepted explanation for Governor Sola’s 1818 decision to move the first church to its location on top of a trash pit is that the 1815 flood destroyed the foundation for the first church. There is no evidence – yet — that the foundation was destroyed in the 1815 flood but Bancroft in volume 1 of his History of California concluded the reshaping of the river’s banks during the 1815 flood endangered the foundation or that Sola believed the reshaped banks endangered the foundation. La Placita is considerably further from the river than the (probable) location of the original site for the church.

There may have been additional reasons Governor Sola moved the church to the La Placita location.

He may have sited La Placita near Yang-Na’s Yovaar; that is, that Governor Sola transplanted the practice used in more complex Indian communities in New Spain rather than following Spanish urban planning law and that he sited La Placita opposite the Tongva central spiritual space.[42]

Also, Indian labor built everything in Los Angeles. By placing a church in front of Yang-Na, Sola – even if not intentionally but probably intentionally –attracted free labor. The church was to include Indians as congregants when it was built in 1818 (completed in 1822). By 1836, the Indians that built the church were seen as “dirty” and offensive to the “white” people, and removed what remained of the Indian village from in front of the church.

Feliz adobe: An old adobe house built in the 1830s by heirs of Vicente Feliz.[43] The rancho was granted 1795-1800 to Jose Vicente Feliz. Substantially rehabilitated, it is now the Park Ranger station on Zoo Drive.

Union Station: Old Chinatown was demolished to clear land for Union Station. A boundary of Old Chinatown is in the Rest Area at 700 North Alameda, designated by a line of bricks. Casa de Lugo, built in 1836, became part of Old Chinatown before its demolition. This area was likely part of pre-contact Yang-Na.

After the return to the present

We can see through the portals set in our familiar present to a time imperfectly remembered..

[1] Hugo Reid’s Tongva wife Victoria signed the deed transferring her property to Don Benito Wilson with an X. She was probably illiterate. Her mentor Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné was literate, a factwhich led to her success in life, but Eulalia was not a native Californian. She was the midwife at the birth of future governor Pio Pico.

[2] African-American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer and statesman. He described his experiences as a slave in his 1845 autobiography Frederick Douglass: an American Slave.

[3] Freeborn African-American author of the 1853 memoir Twelve Years A Slave.

[4] Doyce Nunis, Jr. and Harry, Knill, Tales of Mexican California (Bellerophon Books 1993)

[5] Leo Carrillo, The California I Love (Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 1961)

[6] Bernice Eastman Johnston, California’s Gabielino Indians (Southwest Museum, Los Angeles 1962), pp. 7-8.

[7] For some time, ethnologists and archeologists disputed the origin of the plank boat. Several scholars contended the origin was Polynesian. Others contend the origin was local in Southern California. See, Yoram Meroz, “The Plank Canoe of Southern California. Not an Import, But a Local Innovation,” in John Sylak-Glassman and Justin Spence (eds.) in Structure and Contact in Languages of the Americas, Survey Reports , Volume 15 (UC Berkeley 2013), pp. 103-188. http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~survey/documents/survey-reports/survey-report-15.07-meroz.pdf. (Retrieved /19/2018)

[8] Jack S. Williams, The Tongva of California (Powerkids, 2003) p. 23.

[9] Meroz, op cit., there is no pagination on the 0n-line article.

[10] Torben C. Rick, Jon M. Erlandson, Rene L. Vellanoweth, Todd Brajes, “From Pleistocene Mariners to Complex-Hunter-Gatherers: The Archeology of the California Channel Islands.” Journal of World Prehistory (September 5, 2005) Issue 19, pp. 169-228.

[11] The Holocene Epoch is the current period of geologic time. The Holocene Epoch began 12,000 to 11,500 years ago at the close of the Paleolithic Ice Age. See, Mary Bagley, “Holocene Epoch: The Age of Man,” LiveScience, March 27, 2013. https://www.livescience.com/28219-holocene-epoch.html. (Retrieved 5/19/2018)

[12] Bernice Eastman Johnston, op cit.,, pp. 1-5. The map that page 1 shows Tongva villages at the time of the Portola expedition. Eastman included the road to Yang-Na from the San Gabriel Valley to Yang-Na and the road from Yang-Na over the Cahuenga Pass. Sheo omitted, however, “Calle de los Indios,” which led to Santa Monica. She also omitted the road that led from Yang-Na to El Portezuela, which was at the base of Griffith Park.

[13] The Spanish referred to both the Tongva people in the San Fernando Valley and the nearby Tataviam people, who spoke a different language, as Fernandeño.

[14] Mary Q. Sutton, “People and Language: Defining the Takix Expanion into Southern California. Pacific Coast Archeological Society Quarterly, Volume 41, Numbers 2 & 3. (2009). Pp. 31- 92.

[15] Eastman, Op Cit., pp. 2-5.

[16] See, e.g., Sherburne Friend Cook, Population Trends Among the California Mission Indians. (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1976). Robert F. Heizer, et al., Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8 (Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1978). Alfred Louis Kroeber, Handbook of the Indians of California (Washington, 1925, republished as a paperback in 2012 by Dover Publications).

[17] John W. Robinson, “Winged Feet in the Dust: Long-Distance Trade Routes in Aboriginal California, The California Territorial Quarterly, Number 52, Winter 2002), pp. 4-17. Bernice Eastman Johnston, California’s Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum, Highland Park, 1962). Aboriginal California Three Studies in Cultural History (The University of California Archaeological Research Facility, second printing 11966), James T. Davis, Trade Routes and Economic Exchange Among the Indians of California (Ramona, California, Ballena Press, 1974)

https://www.desertusa.com/desert-trails/native-americans-trails.html. Jay Sharp, “Native American Trails.”

[18] Diary of Gaspar de Portolá During the California Expedition of 1769-1770, originally published in the Academy of Pacific Coast History, v. 1, no. 3 (October 1909). Edited by Donald Smith, Assistant Professor of History and Geography, University of California, Frank Teggart, Curator of the Academy of Pacific Coast History, publisher Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. The editors obtained the manuscript from the Bancroft Library, at Berkeley. The manuscript arrived with other materials that H.H. Bancroft sold the university in 1905. The manuscript Teggart used was preserved in the Sutro Library, San Francisco. Bancroft obtained the manuscript from M. Alphonse Pinart, who purportedly obtained it from Mexico City on October 10, 1881.

[19] James D. Hart, A Companion to California, (New York, Oxford University Press 1978), page 488.

[20] W.W. Robinson, The Indians of Los Angeles: Story of the Liquidation of a People (Glen Dawson: Los Angeles, 1952). Pp. 16-20. Robinson did not footnote, but his source is evidently the records of the ayuntamiento in the municipal archives in the Piper Tech building. Robinson estimated the 1836 population of Yang-Na as 255, 553 in the whole district of the city (He called Los Angeles a pueblo but as of 1835, it was a Mexican city).

[21] Eastman, op cit., page 5.

[22] Americans referred to the Spanish speaking grantees as “Californios.”

[23] Carrillo, page 61.

[24] The Autry’s Collections online. http://collections.theautry.org/mwebcgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=ocn463454433;type=106.

[25] The story of Toypurina may be found in Steven W. Hackel, “Sources of Rebellion: Indian Testimony and the Mission San Gabriel Uprising of 1785,” Ethnohistory 1, October 2003; 50 (4), pp. 643-669.

[26] Jay Correia, State Historian III of the California Office of Historic Preservation, wrote in email correspondence to Phyl van Ammers on August 16, 2016:

“CHL No. 655, designated in 1958, appears to be based entirely on Herbert Eugene Bolton’s Fray Crespi, Missionary Explorer, 1769-1774. (Page 146ff)”

The California Office of Historic Preservation received a letter from historian Lynn Bowman (Mrs. John C. Bowman) on about June 28, 1972, stating the historical marker was misplaced. From Mrs. Bowman’s letter:

“When Capt. Gaspar de Portolà in his expedition of 1769 — the first party of exploration up the California coast — came to the Porciuncula River, they camped for the night. According to diaries of members of the party, they stopped before crossing the river and then, the next day, crossed it. Their encampment therefore would be on the east side of the river, where as marker by the Elysian Hills notes the spot as on the west side…..

“W.W. Robinson, the historian, agrees with me that undoubtedly the difficulty of placing the marker among the railroad tracks on the east side caused it to be put where it is.”’

State historian Jay Correia attached a copy of this letter in his email correspondence with Phyl van Ammers on August 17, 2016.

- W. Robinson (1891-1972) wrote many pamphlets, articles and books on Southern California History. His papers are located at UCLA: Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library. Robinson wrote Land in California: The Story of Mission Lands, Ranchos, Squatters, Mining (University of California Press, 1979). He moved to Los Angeles in 1919 and worked as a professional property title researcher for the Title Guarantee and Trust Company and was later its vice president.

He was qualified to give an opinion about the campsite’s location but, other than the belief – supported by Father Crespi’s diary entries on August 2, 1769 and on August 3, 1769, when the expedition forded the river, the description in Mrs. Bowman’s letter is only a little helpful. That is, Robinson believed the tracks on the east side of the river made it difficult to locate the marker in its true location, “Map of the plaza, showing the old plaza church, public square, the first gas plant and adobe buildings.”

[27] Complete list of historic locations in Los Angeles is on the Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks, website. http://ohp.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=21427. (Retrieved 5/10/2018)

[28] Not the naked old man, though.

[29] Id, “Foreword,” Carl S. Dentzel, Director, Southwest Museum.

[30] See, Donald Ray Culton, Charles Dwight Willard: Los Angeles City Booster and Professional Reformer (1888-1914). Unpublished PhD dissertation, 1971, University of Southern California, The Graduate School. Culton: “The Herald’s History of Los Angeles, as it was popularly called, was well-written, with a relaxed style, best known (though not altogether accurate) histories of early Los Angeles.” Also, “without the encumbrance of handicaps, such as footnoting and excessive care with facts, his progress was swift.” Pages 160-162. The full text is available on-line. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t16m3k352;view=1up;seq=5. (Retrieved 4/10/2018)

[31] Richard Orsi, Sunset Limited: The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Development of the American West 1850-1930, (University of California Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 2005), “Partnerships with Booster Groups,” pp. 143-148.

[32] From Michael Holland, City Archivist. Documents from the city archives are on the USC digital library. 10/12/2017. http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/p15799coll88.

[33] Huntington Library, digital collection, http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15150coll4/id/12899/rec/1. (Retrieved 5/9/2018). A.G. Ruxton was a surveyor.

[34] National Park Service, Historic Monument No. 145.

[35] Edwin A. Beilharz, Felipe de Neve: First Governor of California (California Historical Society, San Francisco 1971)

[36]Currently the accepted name is “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río Porciúncula” (in English, “town of our lady the Queen of Angels of the River Porciúncula”). Father Juan Crespi had named the river – the Los Angeles River – Porciúncula in August 1769. Los Angeles historian Doyce B. Nunis, Jr. argued the town’s original name was El Pueblo de la Reyna de Los Angeles in The Founding Documents of Los Angeles, A Bilingual Edition. (Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, 2004). Doyce B. Nunis, Jr. was a respected historian and longtime faculty member of USC’s Department of History. Nunis chronicled local history as editor of Southern California Quarterly, the journal of the Historical Society of Southern California. See also, Theodore E. Treutlein, “Los Angeles, California: The Question of the City’s Original Spanish Name,” California Historical Quarterly 55, no. 1 (1976) and Harry Kelsey, “A New Look at the Founding of Old Los Angeles,” California Historical Society Quarterly 55 no. 4 (1976), pages 327-339,.

[37] See, Miroslava Chavez-Garcia, Negotiating Conquest: Gender and Power in California, 1770s to 1880s. (University of Arizona Press, 2nd edition 2006).

[38] Abigail Hetzel Fitch, Junipero Serra: The Man and His Work, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (November 21, 2015) This book was first published by A,C, McClurg & Co. 1914), page 332 of the 1914 edition.

[39] Governor Diego de Borica founded Villa de Branciforte in what is today Santa Cruz in 1797. San Jose, Los Angeles and Branciforte were the three secular pueblos founded during the Spanish Colonial era.

[40] Blake Gumprecht, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death and Possible Rebirth, (John Hopkins Press, 1st paperback edition 2001 )pp. 33 and 34.

[41] Heizer, op. cit, page 40, note 86

[42] See, Logan Wagner, Hal Box, Susan line Morehead, Ancient Origins of the Mexican Plaza (Austin, University of Texas Press, 2013).

[43] Mildred B. Hoover; Hero Rensch, Ethel Rensch, William N. Abeloe, Historic Spots in California. (Stanford University Press 1966)

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.