Honey Talks About Water

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

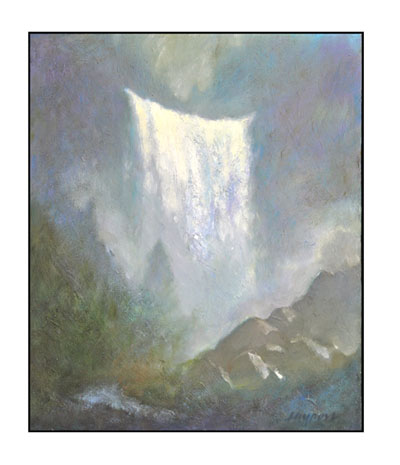

Vernal Falls Copyright 2015 Bob Layport

A few weeks ago, my friend Susannah Wilson drove her eight-year old granddaughter and me up to Lake Almanor in Plumas County. Susannah and her brothers own a cabin on Lake Almanor. Their grandparents built the cabin, so she has been going to the lake on and off most of her life.

We drove up there from Grass Valley, stopping once to look at Yolo River as it streamed over giant stones, and stopping again in Quincy to go to the local museum.

Spanish Captain Luis Arguello named the river up there “Rio de las Plumas” in 1820. The Feather River is the main tributary of the Sacramento River. After the discovery of gold in 1848, towns sprang up in the area. The Beckwourth Trail, established by James Beckwourth in 1850, was the predecessor route to State Route 70 built in 1934. Ina Coolbrith’s family entered California on the Beckwourth trail, led by James Beckwourth on the first trip he guided over the mountains. Although Susannah is an expert driver and knows the routes like the back of her hand – some of her ancestors homesteaded up there – I cannot imagine my driving that route much less imagine how people crossed that formidable terrain before paved roads.

Yolo River Copyright 2015 Susanne De Marie Wilson

Lake Almanor is a large reservoir formed by Canyon Dam on the North Fork of the Feather River, as well as Benner and Last Chance Creeks, Hamilton Branch and natural springs. The meadow flooded a longstanding Yamani Maidu village site in 1914. PG&E owns the reservoir now and uses it for hydroelectricity production. It looks as if there is a lot of water. It’s pretty cold.

We went grocery shopping in the nearby town of Chester. A man outside the market had a petition calling for people to stop people in Los Angeles from stealing “our” water. I had never heard about Chester before I went on the trip with Susannah, and I hadn’t known that when I lived in Los Angeles I had been stealing water from them. Los Angeles gets half it water from the Colorado River and Northern California. The State Water Project collects water from rivers in Northern California, including the Feather River and the Delta. He was enthusiastic so I apologized for not being able to sign his petition. I said I did not live in Plumas County so I couldn’t sign. He asked, smiling, where I lived. I lied and said I lived in Los Angeles to rile him. He stepped back and looked at me for a long time as if the devil had just emerged from hell.

Lake Almanor, copyright 2015 Susanne De Marie Wilson

California’s water system, policies and laws are too complicated for me to understand, at least, not for long. Professor Norris Hundley’s The Great Thirst: Californians and Water (Revised edition 2001) sparked an epiphany but it didn’t last.

The Biltmore Hotel downtown is a synthesis of Spanish-Italian Renaissance Revival, Mediterranean Revival and Beaux Arts styles. The inside is decorated with frescos and murals, carved marble fountains and columns, artisan marquetry, heavily embroiled imported tapestries and draperies. The ornate swimming pool is a mix of Roman bath and Gilded Age ocean liner. California’s American Planning Association has its yearly meeting there. This year’s agenda shows the APA discussed water.

In 1996, I attended a water policy conference at the Biltmore that took up most of the first floor. I reached Los Angeles to attend the conference by taking the train from Madera. In those days, the Madera station consisted of a bench and two paper notices telling passengers how to phone 1-800-USA-Rail. A modest shelter now stands against the pitiless heat of summer in the Central Valley. My 1996 re-entry from rural California to the downtown I hadn’t seen in over twenty years was through Union Station.

Back then, participants and instructors at the water policy conference discussed Proposition 218, an initiative that sought to ensure charges for water would be linked to the costs of service to individual properties. Prop 218 amended the California Constitution, which requires the local government to have a vote of the affected property owners for any proposed assessment. The California Supreme Court extended Prop 218 protections to water rates charged by local governments. [Bighorn-Desert View Water Agency v. Verjil (2006), Richmond v Shasta Comm. Services (2004)] In Capistrano Taxpayers Association, Inc. v. City of San Juan Capistrano (2015), the Fourth Court of Appeal held that because Prop 218 prohibits charging more for a service than it costs to provide, the policy of charging higher rates to users of more water was unconstitutional. The decision compromises Governor Brown’s strategy for reducing water use through local tiered water structures based on amount of water used.

According to the San Jose Mercury on April 22, 2015:

“It’s been 19 years since voters passed one of the worst initiatives in California history: Proposition 218, which micromanages and severely limits the way public agencies can raise money.”

In 2006, this time in a UCLA seminar building, I took a class on California water policy and law. After the class, I asked the lecturer about the policy part. I hadn’t heard him say a word about what sound public policy was, much less how the state laws implemented that policy. He said the law is the policy. With water, you start out with the morass of water law cases and legislation and interpretations of that legislation, and, if you think you want to do that, you could improvise a policy interpretation.

Usually you determine first what your goals are, and then you implement those goals with policies. That’s not how water policy works in California. Although other Western states use a “prior appropriation” system of laws, California’s system is a hybrid of prior appropriation and property rights derived from English law called “riparian rights.” Riparian rights allocate water according to who owns land along the watercourses. Prior appropriation water rights is the legal doctrine that the first person to take a quantity of water from a water source for “beneficial use”—agricultural, industrial or household —has the right to continue to use that quantity of water for that purpose. Subsequent users can take the remaining water for their own beneficial use provided that they do not impinge on the rights of previous users. Our water law depends on a myth: that the water is not all interconnected. See, http://www.propublica.org/article/video-groundwater-explained. (Retrieved July 22, 2015)

In the ancient past, California had occasional mega-droughts that lasted decades. In two cases in the last 1200 years, these dry spells lingered for up to two centuries. Tree ring analyses suggest one mega-drought occurred from about 900 AD to 1000 AD. The second long-lasting drought occurred from about 1100 to 1300 AD. Analysis of very old Native American bones supports the tree ring study. Indians in California were shorter during periods of drought than in other periods, meaning those examined went through extended periods of starvation.

Jeffrey Mount at UC Davis’ Center for Watershed Sciences argues that the state’s accounting of water use is misleading. That is, the state counts wild and scenic rivers. It’s impractical to get water out of them for any kind of human use. He says the right water pie includes net usage of water from interconnected river and aqueduct delivery systems. By his accounting, agriculture gets 62 percent, urban water users 16 percent, and environmental purposes 22 percent. “Environmental purposes” includes keeping seawater out of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta — the sources of much of the state’s drinking water, managed wetlands, and maintaining “insert flows” in water used for recreation and/or environmental reasons.

The federal Central Valley Project’s primary source is Lake Shasta, and it mostly provides water to farms in the San Joaquin Valley. The California-run State Water Project draws most of its water from Lake Oroville (Like Lake Shasta, Lake Oroville is a dammed reservoir.)

Marc Reisner’s 1986 Cadillac Desert, subtitled The American West and Its Disappearing Water, concluded that the West’s development under the American occupation had serious long-term negative effects on the environment and water quantity. In 1997, a PBS affiliate in San Jose produced a four-part television documentary based on the revised book, which included “Mulholland’s Dream,” “An American Nile,” “The Mercy of Nature,” and the “Last Oasis.”

In dry years, like now, groundwater makes from 46 to 60 percent of supplies. Little precipitation means little replenishment. Farmers use groundwater even in wet years to irrigate their crops. To make up for curtailed surface deliveries, farmers pull more water out of the ground.

California is the nation’s leading producer of almonds, avocados, broccoli, carrots, cauliflower, grapes, lettuce, milk, onions, peppers, spinach, tomatoes, walnuts and dozens of other commodities. The state produces one-third of the nation’s vegetables and two-thirds of our nuts and fruits. Almonds use a stunning 1.1 trillion gallons of water each year, most of which is delivered from river diversions or groundwater.

Over-draws on groundwater over the years, not just now, led to the sinking of the Central Valley floor. Unlike most coastal communities where salt has direct outlets to the ocean, in parts of the Central Valley there are inadequate outlets. Increasing salinity is the largest long-term chronic water quality impairment to surface and groundwater in the Central Valley and results in pollution of drinking water sources for some communities in the Central Valley.

These figures do not include other water quality concerns. Herbicides and pesticides contaminate groundwater. In cities, rain water rushes down concrete streets, filled with industrial and residential contaminates. I’ve seen painters wash out their paint cans into the streets. Car wash, dry cleaning, faucet factory effluent and asbestos, tires, dead cats, kitty litter, everything rushes along the concrete streets and down municipal stairs into drains that carry the mess to bays and rivers. The water channeled through the concrete-lined LA River reaches the sea without permeating into the groundwater to replenish it. The water in our toilet tanks is drinking water quality.

My yards, front and back, are planted with native plants. I killed the grass by rolling large cardboard sheets I bought from a paper mill in Oakland over the grass. A tree company yearly dumps wood chips in my driveway. A delivery of wood chips comprises the volume that would fill a two-car garage so it takes a long time to carry those chips into the backyard and fill up the spaces but the result is I don’t have to mow lawns, the native plants attract native bees, and – each year – the plants grow. I no longer have to weed.. Succulents, cactus and rock gardens work better but rocks are really heavy and I’m an old woman so this way was easier for me.

I attempted to convince my neighbor to do the same thing but she replied, “I like a nice lawn.” Her lawn is brown crab grass and weeds mowed neatly. Lawns belong in wet climates. Because of this drought and water regulation, the “nice lawns” are mostly dirt if the homeowners don’t turn on their sprinkler systems at night when they think no one will notice.

When I was a land use planner in Destin, Florida, a woman stormed into city hall with a bucket of dead fish. These were creepy fish with boiled white eyes. She believed the city’s sewage treatment plant was responsible for killing the natural lake in front of her homeowner’s association. She was indignant.

The director of Community Development looked in the bucket. He said, “The water is turquoise. We don’t have turquoise water. You have been fertilizing your lawn, haven’t you?” She nodded meekly. “The nitrogen in the fertilizer is killing the lake,” he said. Recall, if you will, all those television commercials for ways to kill weeds so you may have an emerald lawn without dandelions. Imagine how the massive use of herbicides and pesticides in rural and urban areas all over the country affects our water. Monoculture, which is our primary way of farming, is heavily dependent on chemicals.

The Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) warns that El Nino won’t end the drought and that proposed reservoirs are no panacea.

There may be no panacea except to empty California of a lot of its people and return to the population numbers of the Native Americans who lived here pre-contact. This is the West. It is dry.

Short of depopulating the state, mitigation success depends on a big change in outlook. Modest success means changing our infrastructure so that the rain we have may replenish our aquifers. Mitigation will mean organic agriculture and will mean the elimination of monoculture and the substitution of water intensive agriculture with less-intensive water use crops. Success will mean the restoration of our rivers and the creation of parks along waterways to replace industry. Success will mean the reduction of our meat consumption because animals that are raised to eat consume crops raised for them.

Success means teachers in our schools and park programs that teach children about nature.

This drought will end and people will forget as soon as it rains. Before we all forget, this time is an opportunity to reflect on the fact that a sustainable future for the human race – if we destroy the planet, we will disappear, and the earth will heal – means changing everything we are doing, not only our use of water.

Read, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/1579SDGs%20Proposal.pdf.

.

.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.