Honey Talks About Two journeys through California from Los Angeles in 1912

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

1912 driving costume.

An Englishman named J. Smeaton Chase settled in Southern California in 1890, when he was twenty-six. The best known of Chase’s books is California Coast Trails: A Horseback Ride from Mexico to Oregon, published when he was forty-seven about his travel on horseback on trails from San Diego to the Oregon border wearing a broad-brimmed Stetson hat, riding breeches, leather puttees and a tweed coat.

From Chase’s California Coast Trails:

“Carl Eytel the painter and I were riding down the south road from El Monte one midsummer morning, with our blankets rolled behind our saddles and other appurtenances of outdoor living slung about us. Ever since I had lived in California I had been waiting for an opportunity to explore the coast regions of the State. At last the time had come when I could do it; and Eytel, my companion on other journeys in the mountains and deserts of the West, was free to join me for the southern part of the expedition.

“Our object was to view at our leisure this country, once of such vast quiescence, now of such spectacular changes. Especially we wished to see what we could of its less commonplace aspects before they should have finally passed away: the older manner of life in the land; the ranch-houses of ante-Gringo days; the Franciscan Missions, relics of the era of the padre, and the don, the large, slow life of the sheep and cattle ranges, and whatever else we could find lying becalmed in the backwaters of the hurrying stream of Progress.”

It remains possible to drive a car through California towing a horse trailer to riding trails. No one can today, however, duplicate Joseph Smeaton Chase’s entire horseback journey. The people he met along the way are long gone, although their great-grandchildren may be around. If the families did not leave the state, the descendants of the Welsh, Mexican, Scottish, Italian-Swiss, Scandinavian and Irish families that welcomed him into their homes and refused payment for their hospitality are probably absorbed into the fabric of urban and suburban California.

Chase’s map, from his California Coast Trails.

Much of the California landscape he saw a little over a hundred years ago has been transformed in large part because of the automobile. Chase saw automobiles along the way but didn’t think them useful for seeing what he wanted to see: not just sheep and cattle ranches, but all the plants, the sweep of color of purple lupines and the golden Eschscholtzia californica, eucalyptus, rivers, redwoods, and the sea as it grumbled in its old voice against black rocks.

Because Chase wrote in a clear style, and because he was a compassionate and erudite man, the books he wrote may be read as though a contemporary of ours tells us a story about another country. That country is the past.

California Coast Trails is available free on Internet. The site also provides Chase’s photographs. http://www.ventanawild.org/news/fall05/chase/. (Retrieved 12/15/2016).

Joseph Smeaton Chase was born in Islington, now a London borough and arrived in Southern California when he was twenty-six.

He lived frugally for the next few years in the mountains near San Diego and later tutored a rich rancher’s children in the San Gabriel Valley. The inheritance he brought with him from England vanished in a bank failure.

His name appeared in the Los Angeles phone directory in 1893 and he worked in a Los Angeles camera shop and then, for many years, he worked as a social welfare worker at the Bethlehem Institutional Church in Los Angeles. The Institute was a non-denominational social and educational organization serving working class people and immigrants, which covered six city lots. It ministered to Chinese, Japanese, and Russian immigrants. Somewhere in his travels or through his work, he learned Spanish.

His first book, Yosemite Trails, was published in 1911, and in the same year, he published Cone-Bearing Trees of the California Mountains. California Coast Trails was published in 1913.

He moved to Palm Springs in 1915. During the period 1915-1919 he published: The California Padres and Their Missions, written with well-known California author and naturalist Charles Francis Saunders; The Penance of Magdalena and Other Tales of the California Missions; California Desert Trails; and Our Araby: Palm Springs and the Garden of the Sun.

Chase married Elizabeth White in 1917. He was 53 and she was forty. Isabel’s sisters Cornelia White and Dr. Florilla White had purchased Dr. Welwood Murray’s hotel – the first Palms Springs hotel, built of railroad ties in 1893 – now the “Little House” in the Village Green Heritage Center in Palm Springs.

He died in Banning in 1923 at age 59 after several years of ill health. Isabel outlived him by almost forty years, dying in 1962.

Chase at Laguna:

“A few miles along a road that wound and dipped over the cliffs brought us by sundown to Aliso Cañon. A brackish lagoon lies at the mouth, barred from the ocean by the beach sands. The walls of the cañon are high hills of lichened rock, sprinkled with brush whose prevailing gray is relieved here and there by bosses of olive sumach (sumac?). A quarter-mile inland we struck tokens of the neighborhood of a ranch, and here made camp under a rank of fragrant blue gums populous with argumentative kingbirds and cheerful orioles.

“The landscapes of California have been greatly enriched by the acclimatization here of the eucalyptus. It is not often that the presence of an imported ingredient adds a really natural element to the charm of scenery; but the eucalyptus, especially the globulus variety that has become so common throughout the State, has so truly native an appearance that it seems as if its introduction from Australia must have been more in the nature of a homecoming than of an adoption. The wide, treeless plains and valleys which once lay unrelieved and gasping under the summer sun, and inspired similar sensations in the traveller, are now everywhere graced by ranks and spinneys of these fine trees, beautiful alike, whether trailing their tufty sprays in the wind, or standing, as still as if painted, in the torrid air.

“When the winter rains come there are no trees that so abandon themselves to the spirit of the time. With wild sighs and every passionate action they crouch and bend as if in the very luxury of grief. and toss their tears to the earth like actors protesting their sorrows on a stage.

“The long, scimitar-like leaves are as fine in shape as can be imagined, and each tree carries a full scale of colors in its foliage, — the blue-white of the new, the olive of the mature, and the brilliant russets and crimsons of the leaves that are ready to fall. The bark is as interesting as the foliage, its prevailing color a delicate fawn, smooth enough to take on fine tone reflections from soil and sky. Long shards and ropes of bark hang like brown leather from stem and branches, making a lively clatter as they rasp and chafe in the wind, and revealing, as they strip away, the dainty creams and greenish-whites of the inner bark.

“The tree’s habit of growth sets off its beauties to the best advantage, long spaces of the trunk, arms, and smaller branches showing all their handsome colors and “drawing” between the dense plumes of foliage. In early summer the tree flowers with a profusion of blossoms uniquely tasteful, and later, the seed-vessels are as quaint and curious as rare seashells. To crown all, the tree is as fragrant as sandalwood, and the scent a hundred times more robust than that exotic perfume, which is fit only for seraglios and the effeminate paraphernalia of Mongolian decadence.”

Writing about the San Fernando Valley:

“The Mission of San Fernando, which was founded in 1797, probably never had as great claims to notice, on the score of beauty, as had some others of these interesting monuments; but the heavy low building, with its long line of arches, red-tiled roof, and elementary campanile, is pleasing for its simplicity, and seems appropriate to the humility of the order of St. Francis. The church itself is in ruins, and shows plain evidences of the unhallowed industry of treasure-seekers with crowbars. An old Mexican now guards the place, unlocking for a small payment wormy doors with fiddle-like keys, and leading the visitor by precarious stairways to moldy lofts and cellars, peopled with shades of priest and neophyte, comandante and soldado de cuero.

“The San Fernando Valley, through which I rode next day, is an example of those famous ranches in which the lands of California were held by grantees of the Spanish or Mexican Government. This was one of the last of them to remain unbroken, and was now in process of being surveyed for selling off to settlers of the new order. It opened before me m league on league of grain, waving ready for harvest. a crop to be measured by the thousands of tons. The landscape flickered under an ardent sun and as we plodded hour after hour along the tedious straight roads, escorted by clouds of pungent dust, I panted for the clean, crisp breezes, which I knew were blowing just beyond the low range of the Santa Monica Mountains to the south. No single tree offered respite of shade, and the two or three ranch houses we passed looked almost hideous in their blistering whitewash.

“Gradually the valley began to close toward the west, where the wooded Simi Hills rose to meet the higher Santa Susannas; and turning at last southward I struck into the main coast road, and came by sundown to the little village of Calabasas. drawing reins before a small building which bore the sign of the Hunter’s Inn.”

Oxnard and Port Hueneme:

“Hueneme is the ghost of a once flourishing town. On its one business street the vacant stores, with their hopeless signs of To Rent, stand ranked in shabby idleness, like a row of blind beggars. Not very many years ago this was a lively little port; but a beet-sugar factory sprang into existence a few miles to the north, and that, with its joint advantage of a railway, was too much for Hueneme. The greater part of the population and not a few of the houses themselves made off bodily to the new center and left Hueneme nothing to boast of but its smooth, clean beach and its busy past, during which (as a gloomy citizen assured me) the place had been the scene of as much traffic as ‘any other two blamed towns of the county.’ Now, only one small coasting steamer calls at long intervals, and occasionally a lumber schooner puts in with its fragrant load from the northern forests, while a stage carries scanty mails and infrequent passengers over to the railway at Oxnard, ‘the hated rival.'”

Santa Cruz:

“An easy ride next morning through quiet rural roads, and a village or two where loafers on sugar-barrels were dallying with watermelons, brought us to the city of Santa Cruz, lying at the north bend of Monterey Bay. It has a population of some twelve thousand, and seemed to me a staid, ordinary kind of place, though it is much in request as a rendezvous for conventions, and is certainly endowed with an unusually fine bathing-beach. Here once stood another of the Franciscan Missions, but no trace of it remains.

“The mountain belt that rises to the north of Santa Cruz carries a particularly fine forest of redwoods. I could not think of missing these noble giants, so once more I abandoned the coast for a few days and struck directly into the mountains. The road followed the course of the beautiful San Lorenzo River, and I was soon again in the companionship of the trees, — a mingling of sequoia, spruce, alder, bay, box elder, and maple. The cañon is a deep one, and the narrow road is cut into its western side, giving fine views up and down the wooded gorge.”

Chase’s photo of the Nacimiento River on the border between Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties.

Chase rode Chino and, after Chino was exhausted, Anton along the coast. Jackson A. Graves and several companions, including his wife, his son, and possibly another son at the wheel, drove from their home in Alhambra. Chase’s horses needed pasture and water. Graves’ car needed gas stations and mechanics. Graves’ report on their trip is “A Motor Trip in 1910,” in John and LaRee Caughey’s Los Angeles: Biography of A City (University of California Press 1977), pages 249 to 253.

Graves (1852-1933) was president of the Farmers & Merchants National Bank for twelve years, a member of the Los Angeles Clearing Housing Association for over twenty years and its president in 1907. He was custodian of all securities of the National Currency Association of Los Angeles during World War I. His family made the trip to California by the Panama Canal in 1857 and settled in Yuba County. He graduated from St. Mary’s College near San Francisco and earned a B. A. and an M.A., and then he moved south to join the law firm that became Graves, O’Melveny and Shakeland. He married Alice H. Griffith, the only child of J. M. Griffith, who founded a lumber company in Los Angeles in 1857 that covered six acres of land around North Alameda Street.

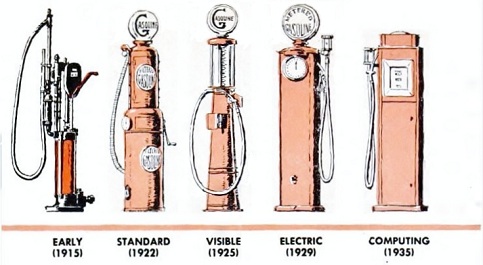

The first public gasoline servers were called filling stations. These were curbside hand pumps, and they began appearing in 1907. John H. Lienhard, cited at the end of this essay, wrote:

“The gas station started taking shape around 1910. By 1920 it was well-defined. It was a small building with gas pumps in front. But it also offered supplies – tires, batteries, and oil. It offered simple services – lube jobs and tire patching.”

When the gas station “started taking shape,” shopkeepers filled a five-gallon can from behind the store and brought it to the customer’s car to fill it. In 1910, Gilbert & Barker Manufacturing Co. manufactured the first gas pump, which used an underground storage tank.

First gas pumps. American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

The 1925 “visible sight” pumps with a glass cylinder so that consumers could see the amount of gas they took into their vehicles stood at a station on the pass between Eagle Rock and Highland Park when my mother got her license in 1953 to the dismay of pedestrians throughout the eastern side of the Los Angeles River.

In 1903, California became the leading oil-producing state in the United States. Production reached 78 million barrels by 1910.

The first paved road in the United States was a one-mile section of concrete road just outside of Detroit. That was in 1909, so Graves and his companions must have driven on dirt roads.

Graves followed the Butterfield Overland Stage Route through Beale’s Cut at San Fernando Pass, south of Saugus and Newhall and followed El Camino Viejo, one of the branches of the Indian road before Europeans arrived in California.

Postcard: Newhall Grade, 1920.

The Graves’ Franklin raced with a train on their way into the Tehachapi. The Southern Pacific traveled part of the route as the automobile road but then turned north at Palmdale to Mojave and northwest over Tehachapi Pass, which means Graves followed that route during part of the journey.

Graves drove a six-cylinder Franklin, a luxury automobile. Seven passengers crowded into this car for their journey into California.

From sepia-tinted photographs of a trip my grandparents took through California in a similar-looking vehicle, everyone in an automobile wore flat caps – the women wearing full scarves under the caps – full-length light coats against the dust, and goggles. Driving on dirt roads was dirty.

The long coats called “dusters” became a fashion garment: affluent women wore them even when not in an automobile to reflect that they owned a car.

In Harold Lloyd’s 1924 silent film comedy Hot Water, Josephine Crowell playing the Lloyd character’s mother-in-law sits in the back of “The Butterfly Six” – actually a 1921 Chevrolet – wore a version of the hat and chiffon scarf if the earlier fashion through the streets of Los Angeles. By then, the city’s streets were paved. You may see the streets as they were before potholes on this YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yh3Ooj_njRM. Robert Israel’s music score to this bit of the movie informs the antic drive.

The Graves entourage went up the “Newhall Grade.” It had been too difficult for an automobile to go up this route until 1910. In 1910, the 435-foot-long Newhall Auto Tunnel was constructed. In the 1930s, the hill was blasted away and is now the Sierra Highway.

They left Alhambra at 7 a.m. and reached Bakersfield at 4:45 p.m. Today, that distance – about 120 miles – is covered in two hours. To travel about 120 miles in ten hours, means they traveled at about 12 mph.

The Franklin’s transmission brake, whatever that is, gave out in San Jose, and the oil pump, whatever that is, was not working properly, so they stayed several hours in San Jose for repairs. They then drove to Oakland.

The “Oakland Mole” was the Oakland Long Wharf, an 11,000-foot railroad wharf and ferry pier. From Graves’ story:

“On the Oakland Mole three men in a machine ran abreast of us. They all seemed to be intoxicated. The driver, holding his wheel with his left hand, waved his right hand at us. Just then his machine veered into the fence separating the driveway from the railroad tracks. He ripped off boards, tore of his fenders, smashed his lamps, knocked out spokes of his front wheel and sprung an axle, besides suffering other minor injuries. We hastened out of the way fearing that he might run into us. We had to wait at the Ferry. Before it started the trio appeared, with a much-battered machine. They were in high spirits and evidently thought the accident a great joke.”

In Garberville, the Franklin ran out of gas. “A dwelling was near by. We found a lady from there from whom we got two gallons of coal oil (the Franklin will run on coal oil)….”

They seem to have turned back at some point after Dyerville, a former settlement in Humboldt County, somewhere near Weott.

“On June 13th…the spring that was injured when the bridge broke down, succumbed. We took off the upper half of the spring, reversed it, set the broken end under a bolt passed through the eye of the lower half, held same in place with a clip, securely bolted in place with a flat monkey wrench also held in place by the same clip, over the broken spring, so that the end could not fly up or get sideways. Thus mended, this spring carried us safely six hundred and thirty miles, until we got to San Francisco and had it repaired ….”

Graves concluded:

“We were away just four weeks….Traveling in an automobile is certainly the way to see the country.”

The California State Archives blog, found at https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/twJCUuaVA4eXIA, shows photographs of early automobiles traveling through California, and the dangers of driving in those days. Chase looked for what was becalmed in the backwaters of “the hurrying stream of progress”; Graves was in the hurrying stream of progress.

Graves does not mention much of what he saw on that trip in 1910. I imagine he and his fellow Franklin passengers saw little of the country except as a blur endured for long periods but punctuated by episodes of terror and laughter.

Sources:

https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=42276259.

http://www.ventanawild.org/news/fall05/chase/chasenotes.html.

http://palmsprings.com/history/.

http://www.socialworkhallofdistinction.org/honorees/item.php?id=8.

http://www.americantrails.org/resources/statetrails/CAstate.html.

http://www.scvhistory.com/scvhistory/al2025.htm.

Caughey took Graves’ essay from Jackson A. Graves, California Memories, Times Mirror Press, 1930. This book is available through Amazon.

The Double-Cone Quarterly: A Window to the Wild, Fall Equinox 1998, Volume 1, Number 2. http://www.ventanawild.org/news/fe98/chase.html.

Chase’s, Yosemite Trails (1911), is available on Internet at http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_trails/

John H. Lienhard, Engines of our Ingenuity, No. 975. http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi975.htm.

John Steven McGroarty, California of the South, Vol. IV, (Clarke Publishing, Los Angeles, Chicago, Indianapolis (1933), pp. 681-685.

“The History of Fuels Retailing” 2013, NACS, The Association for Convenience & Fuel Retailing. http://www.nacsonline.com/yourbusiness/fuelsreports/gasprices_2013/pages/100plusyearsgasolineretailing.aspx.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.