Honey Talks About the first plaza in Los Angeles and the unsettling wind

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

In Los Angeles, the disagreeable Santa Ana winds originate inland. Raymond Chandler, in “Red Wind”:

“There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge.”

Many of the streets in downtown Los Angeles are cocked at an angle. They run north-northeast to south-southwest instead of north to south, east to west. Streets begin to run north to south at Hoover. Unsettling winds might be the explanation for why streets around the plaza downtown are set at an angle. Or not.

Raymond Chandler’s plots were so convoluted even he couldn’t always follow them.

The plot of the mystery of why Los Angeles streets run at an angle is as serpentine as a Chandler story.

The simple solution to the street mystery is that the plaza next to the Olvera Street marketplace downtown – laid out between 1825 and 1830 – was cocked at an angle during the years when the plaza was a rectangle. The plaza’s left top corner pointed north, which meant that the streets established after the plaza was laid out followed the plaza’s angle.

Ordinance 114 of Spain’s Law of the Indies required that pueblo plazas should be angled like the Olvera Street plaza; however, the first twist to the plot is that the Olvera Street plaza was established after Mexico gained its independence from Spain. California became a neglected frontier.

Mexico’s influence over California waned. The gente de razón – the people culturally Hispanic – often thought of themselves as separate from Mexico, as Californios. Nonetheless, they established a plaza laid out pursuant to Ordinance 114, an ordinance enacted in Spain in 1573.

Also, although there were routes – several of them prehistoric – through the Los Angeles basin, most of the streets were no more than meandering alleys between houses until after the August 1849 E.O.C. Ord survey completed during the interregnum between Mexican rule and September 9, 1850, when the United States government granted California statehood.

One of the twists to the street story is that the original plaza – probably laid out at the end of unusually dry winter in 1777 when the Spanish colonial governor of California Phelipe de Neve traveled on horseback from Loreto in Baja California to Monterey in Alta California – was also cocked at an angle with its left top corner pointed to the north, as were the plazas of the San Jose pueblo after it relocated in 1797 and (probably) the Branciforte pueblo. There were no other secular pueblos established in Alta California during the Spanish regime.

Plaza Map, Pueblo de San Jose, 1797. Courtesy San Jose History

A further turn in this history maze is that not all town plazas in other parts of North America were angled like the two Los Angeles plazas. Ordinance 114 applied to all Spanish colonial pueblos.

The basis of Ordinance 114 was a Roman town planning principle that plazas should be established at an angle in order to mitigate the unsettling effect of wind. Winds, however, can come from any direction.

After Neve founded the pueblo of Los Angeles and the pobladores initially settled into their brush huts, Neve wrote an instruction for pueblos that mirrored Ordinance 114. If the Law of the Indies applied to all new colonies – and it did – there appeared to be no necessity for Neve to write a mirror provision.

Neve had a different reason for creating the mirror provision, one that had nothing to do with unsettling winds; that is, he had located the 1781 Los Angeles pueblo proper (the plaza, building lots, granary, two administrative adobes and a guardhouse) on what has been variously referred to as a ledge, a terrace, or a mesa at the base of the last Elysian Park hills just below what is today called the Glendale Narrows, about a mile and a half to the east-northeast of the principal Tongva trading village of Yang-Na, which was located around where today’s Los Angeles civic center is.

The governor placed the pueblo proper on the elevated ledge because he was aware the river sometimes flooded surrounding land. In 1769, the first European land expedition led by Gaspar de Portolá i Rovira (1716–1786)

(“Portolá”) passed near that location, and the expedition’s diarist Friar Juan Crespi noted evidence of flooding a little to the north at the confluence of the river and the Arroyo Seco.

Historians disagree on where the first plaza, laid out in 1781, was located.

- M. Guinn, beginning in 1886 when he arrived in Los Angeles, contended the original plaza was located a little uphill of the present plaza. Blake Gumprecht, in The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death and Possible Rebirth, wrote in 2001 that the first pueblo proper, the heart of which was the original plaza, was on a terrace above the river. William David Estrada, in The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space, published in 2008, wrote that there might have been two or three previous plazas. William Mason, in Los Angeles Under the Spanish Flag, published in 2004, wrote:

“The precise location of the very first pueblo site is in doubt. Probably the one thing we do know is that it was not on the present plaza. Vague references indicate that it was to the south, perhaps as much as a mile, around Sixth and San Pedro Streets or Seventh and Alameda Streets…. In

any case, the plaza was probably well south of the present one and on ground which was subject to flooding during unusually heavy rains.”

Gumprecht was correct. The original pueblo proper was built on a fairly narrow ledge above the Los Angeles River to the northeast of the present plaza.

The original pueblo proper’s measurements corresponded to Spanish colonial provisions but, because the ledge was narrow, the pueblo proper had to be cocked at an angle with the top left corner pointed north in order to fit on the ledge. The ledge still exists, and the angle of the hill base across it is about the same as it was in 1777.

Father Juan Crespi recommended the location where he crossed the Los Angeles River as a good site for a mission or large settlement on August 2, 1769. He forded the river at about the point where the Broadway Bridge now crosses it.

From Fr. Crespi’s diary on August 2, 1769, describing the journey from an Indian village where the present San Gabriel Mission is located now to the eastern bank of the Los Angeles River:

“We set out from the valley in the morning and followed the same plain in a westerly direction. After traveling about a league and a half through a pass between low hills, we entered a very spacious valley, well grown with cottonwoods and alders, among which ran a beautiful river from the north-northwest, and then, doubling the point of a steep hill, it went on afterwards to the south. Toward the north-northeast there is another riverbed, which forms a spacious watercourse, but we found it dry. This bed unites with that of the river, giving a clear indication of great floods in the rainy season, for we saw that it had many trunks of trees on the banks. We halted not very far from the river, which we named Porciuncula. Here we felt three consecutive earthquakes in the afternoon and night. We must have traveled about three leagues today. This plain where the river runs is very extensive. It has good land for planting all kinds of grain and seeds, and is the most suitable site of all that we have seen for a mission, for it has all the requisites for a large settlement…”

Portolá followed the Indian road and forded the river on August 3, 1769. The historic state marker at the bottom of Elysian Park Drive on North Broadway erroneously states that the expedition camped there. After fording the river, they headed out on the old Indian road until they arrived at the spring located on the grounds of University High School in West Los Angeles. Crespi:

“At half-past six we left the camp and forded the Porciuncula River, which runs down from the valley, flowing through it from the mountains into the plain. After crossing the river we entered a large vineyard of wild grapes and an infinity of rosebushes in full bloom. All the soil is black and loamy, and is capable of producing every kind of grain and fruit that may be planted. We went west, continually over good land well covered with grass. After traveling about half a league we came to the village of this region, the people of which, on seeing us, came out into the road. As they drew near us they began to howl like wolves; they greeted us and wished to give us seeds, but as we had nothing at hand in which to carry them we did not accept them. Seeing this, they threw some handfuls of them on the ground and the rest in the air…”

On Portolá’s return trip from Monterey in January 1770, they took a short cut over another Indian route through the Cahuenga Pass but otherwise apparently followed the same route as they had followed in August. Crespi noted evidence that the river had flooded during their absence.

It is not certain what route the Juan Bautista de Anza expedition (“Anza”) took in 1776 through Los Angeles. The most likely native trail Anza followed was probably the same one that Portolá. The San Gabriel Mission was founded in 1771 but moved – according to some sources in 1775 and according to others in 1776 – to its present location. If the location that the Anza expedition began its Los Angeles portion of the journey was the site of Misión Vieja, located near the intersection of San Gabriel Boulevard and Lincoln Avenue in Montebello, the former Tongva village of Shevaanga, the distance was about 9.5 miles. If Anza left the mission from its present location, the distance was 7.8 miles.

Anza diarist Friar Font wrote on February 21, 1776:

“… We set out from Mission San Gabriel at a half past eleven in the morning and halted at a half past four in the afternoon at the spot called El Portezuelo having traveled for five leagues following a west-northwestward course with some veering to one side and the other. At two leagues we crossed the Porciuncula River, which carries a good amount of water and runs toward the San Pedro bight, and spreads out and loses itself upon the plains shortly before reaching the sea. The land was very green and flowery and the route had a few hills and a great deal of miry grounds created by the rains. This is why the pack train fell far in the rear.”

A Spanish colonial league at the time was about 2.63 miles or five and a quarter miles. Anza most likely left from the present San Gabriel mission site and traveled the shortest route to the river, which would have taken them to the same place that Father Crespi had noted in his diary in 1769. Fr. Font could not have been correct about the distance from the mission to the river.

On June 7, 1777, several months after he reached Monterey, Neve wrote to Viceroy Bucareli:

“…Three leagues from that mission (the San Gabriel Mission) is the found the Porciuncula River with much water easy to take on either bank and beautiful lands in which it all could be made use of …” (John and LaRee Caughey, Los Angeles: Biography of a City, University of California Press, First Paperback Edition 1977, “Recommending a Pueblo on the Porciuncula,” page 63).

Neve located the future Los Angeles pueblo after following the same route that Portolá had followed – and probably the same route Anza had taken – fording the river at the base of the last Elysian Park hill. He selected the site for the pueblo proper based on Crespi’s recommendation as well as on what he saw on his inspection of Alta California.

The governor reached Monterey but then may have gone north from there to the Guadalupe River, the site Anza recommended for a pueblo in 1776. José Joaquín Moraga founded El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe on November 29, 1777.

Neve traveled south to the Mission San Gabriel in 1781 to wait for the arrival of the settlers from Mexico for the Los Angeles pueblo. Neve’s biographer Edwin A. Beilharz believes that Neve wrote his plans for the pueblo at that time. Soldier José Darío Argüello led settlers from Mexico to the mission and then from the mission to the site of the future pueblo.

Five years later, Argüello traveled down from the Presidio of Santa Barbara to Los Angeles to officially allocate the home sites and farming lots to the heads of families. Bancroft believed from the research that Thomas Savage found in the provincial archives that Argüello prepared a map showing the land allocations in 1786 (the “Argüello map.”).

The zanja shown in the Argüello map was to be gradually extended as the population of the pueblo expanded, moving to the southwest of the original location, through what is today Chinatown, through to the Olvera Street area.

A more current map showing the route of the Zanja Madre at its furthest expansion shows that it began a little north of today’s Broadway Bridge, marked “AT and SF Rlway.” Digitized version of an 1875 map of the Zanja Madre in Los Angeles, credited to Douglas Whitley and Lisa Pierce, Cogstone Resource Management, last modified July 6, 2012. https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=b7c97d8939814c4aac0a223f790b8d2a. (Retrieved 10/30/2016).

The first and second Los Angeles pueblo plazas were laid out according to Ordinance 114 of the Law of the Indies. The first San Jose pueblo plaza was not. When the San Jose pueblo proper relocated in 1797 after a flood, the settlers laid out a plaza that did follow Ordinance 114. That ordinance had been around since 1573, and before that, Roman town planning principles required the same orientation of the plaza.

Ordinance 114, it seems, did not always guide Spanish colonial town planning.

The origin of Ordinance 114 of the Law of the Indies may be found in Roman town planning traditions.

Roman author, architect, civil engineer and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius commonly known as Vitruvius wrote ten books on architecture dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide for building projects. It was the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity. Vitruvius:

“By shutting out the winds from our dwellings, therefore, we shall not only make the place healthful for people who are well, but also in the cases of diseases due perhaps to unfavorable situations elsewhere, the patients, who in other healthy places might be cured by a different form of treatment, will here by more quickly cured by the mildness that comes from the shutting out of winds….”

“On this principle of arrangement the disagreeable force of the winds will be shut out from dwellings and lines of houses. For if the streets run full in the face of the winds, their constant blasts rushing in from the open country, and then confined by narrow alleys, will sweep through them with great violence. The lines of houses must therefore be directed away from the quarters from which the winds blow, so that as they come in they may strike against the angles of the blocks and their force thus be broken and dispersed.”

Vitruvius identified eight winds. Concern over four winds (The north wind, the south wind, the east wind, and the west wind) was the origin of Ordinance 114 of the Laws of the Indies.

Ordinance 114 of the Law of the Indies required new towns to be built with the top corner of the plaza aimed to the north.

In Spanish City Planning in North America, by Crouch, Garr and Mundigo (The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London, England, 1982)(“Crouch”) the authors present two versions of translations of ordinances issued by Philip II in 1573 for the laying out of new towns.

Ordinance 114, as corrected by the authors, provided:

“From the plaza shall begin four principal streets. One (shall be) from the middle of each side, and two streets from each corner of the plaza; the four corners of the plaza shall face the four principal winds, because in this manner, the streets running from the plaza will not be exposed to the four principal winds, which would cause much inconvenience.”

This means that Spanish colonial plazas were to be tilted with one corner facing north and one south; and the other corners should point east and west. Houses were to face the plaza, as houses faced the plaza in San Jose after 1783. Government and ecclesiastic buildings also were to be built to face the plaza. There could be several plazas laid out as a city grew. The towns started with the open space and grew out from it.

Spain established three secular pueblos in Alta California: San Jose (1777), Los Angeles (1781) and Villa de Branciforte (1797).

Yerba Buena – later called San Francisco – began in 1835 when William A. Richardson put up a large piece of canvas stretched on four redwood posts near Yerba Buena Cove. Swiss-born engineer, artist and ship captain Jean Jacques Vioget made the first survey and map of Yerba Buena and made a grid of trapezoidal blocks. His 1839 map of Yerba Buena included space for a plaza. This plaza is today’s Portsmouth Square and it is slightly tilted, as were his other blocks, away from a north to south grid.

The original (1781) and the present (1825-1830) Los Angeles plazas were oriented with the left corner pointed north. The present plaza was reduced to a circle by about 1869. The physical evidence that remains of the original plaza are two roads, the Los Angeles State Historic Park, and a piece of the conduit that comprised the Zanja Madre after 1877.

An early road connected from Calle Principal – the street between the parish church and the 1825 plaza – and connected to Toma Road. Toma Road once continued around the pueblo’s original farm land, now partly occupied by the Los Angeles State Historic Park, and led up past the abandoned original plaza to the toma or head works for the irrigation ditches that watered the pueblo. The top portion of Toma Road is gone, but the route is now followed by North Main Street.

The route that Crespi and Neve – and probably Anza – used to ford the river is now North Broadway and the Broadway Bridge.

Recently, a piece of the conduit built in about 1877 to replace the earlier dirt ditch zanja emerged in the excavation Blossom Plaza in Chinatown.

The Avila house (1818) and the first church in Los Angeles (completed 1822) remain from the second (and present) plaza. The church was rebuilt in 1860, but on the same location.

The original San Jose pueblo (1777) was primitive for quite some time. The layout of this pueblo was reorganized in about 1783, according to H. H. Bancroft in his History of California. This later reorganization was mapped. The reorganized San Jose pueblo had a plaza, but the plaza was not oriented with its left corner pointed north; that is, its design rather followed the contour of the Guadalupe River as it was then. The Peralta adobe remains from that earlier location.

The San Jose pueblo relocated in 1997. This plaza was oriented with its left corner pointed north, as may be seen from looking at a map of Cesar Chavez Plaza, the remnant of the 1797 plaza. Streets radiate from Cesar Chavez Plaza at an angle that reflects the angle of the 1797 pueblo’s plaza.

The Branciforte pueblo was not successful. In 1803 Jose de la Guerra, reported that of its 25 houses only one house was built of adobe. The rest were thatched huts. An adobe house – the Branciforte Adobe or the Craig-Lorenzana Adobe at 1351 N. Branciforte Avenue- remains from the Branciforte pueblo on Branciforte Avenue in Santa Cruz. North Branciforte, which shows up in maps from the 1850s, probably radiated from the Villa de Branciforte plaza. Americans moving into the area called it “Spanish Town” and then “East Santa Cruz.”

North Branciforte Avenue runs at an angle that is about the same angle as the streets radiating from the present Los Angeles plaza and the second San Jose plaza. Branciforte Drive begins with Market Street but in the area that was the villa, it also runs at that angle.

Not all Spanish colonial plazas in areas other than Alta California were aimed with one corner pointing to the north.

The table below is made from information in the maps in Kinsbruner’s The Colonial Spanish-American City and Crouch’s Spanish City Planning in North America, except for information about San Jose.

The severe angle of plaza orientation, however, is only present in the Los Angeles, California and San Jose, California (after 1797) pueblo maps.

Ordinance 111 of the Law of the Indies should be read together with Ordinance 114.

Crouch, et al, in Spanish City Planning in North America argue that Ordinance 114 of the Laws of the Indies – which requires the corners of the plaza face the cardinal directions of the compass – should be read together with Ordinance 111, which required an elevated location. That is, protection from wind is more important where the plaza is high up.

All of the secular pueblos were originally laid out at an elevation above a river: the original Los Angeles pueblo proper was on a mesa or terrace at the base of an Elysian Park hill near the Los Angeles River as it emerged from what is today called the Glendale Narrows a little to the north of today’s Broadway Bridge.

The original San Jose de Guadalupe pueblo proper was laid out near the Guadalupe River at a slight elevation, but that elevation was not high enough to protect it from the flood that led to its relocation. The second location of the San Jose pueblo proper is on higher ground and at a greater distance from the river than the original pueblo proper. It was not, however, on a hill.

Branciforte was on ground higher than the nearby Pacific Ocean and on higher ground than the San Lorenzo River and on the plain of the river but it was not on a hill. The ground slopes upwards from the ocean to the Santa Cruz Mountains. The Santa Cruz Mission, established in 1791, is on a hill. Ordinance 111 applied to pueblos that were not built on the coast. Branciforte was almost on the coast. The Spanish colonial rule about placement of pueblos therefore imperfectly applies to Branciforte.

The 1781 Los Angeles pueblo proper’s location against the base of the hill at the base of today’s Elysian Park nestled it from winds coming from the west. The mesa on which it was built is not very high. The location was not anymore subject to winds coming from other directions than was any other location in the Los Angeles basin.

The 1825-1830 Los Angeles plaza was established on ground that was and is higher than the river; nonetheless, all of downtown Los Angeles remained subject to floods, including the plaza area, until the river was confined to a concrete channel in the 1930s.

Everyone living in the Los Angeles basin experiences the weird Santa Ana winds. Neither the original Los Angeles plaza nor the present plaza area as laid out between 1825 and 1830, however, could have been located to prevent the unsettling experience of the Santa Anas because nowhere in the Los Angeles basin is exempt.

The governor’s instructions for the orientation of plazas mirrored Ordinance 114 but he wrote out his planning principle after he had already laid out the original Los Angeles plaza.

As may be seen from the table above not all of the Spanish colonial plazas followed Ordinance 114.

Felipe de Neve’s detailed Instrucción (September 1782) directed that the pueblo be “exposed to the North and South winds.” On the other hand, the four corners of the plaza were to face the cardinal points (North, South, East and West) in order that the principal streets issuing from them and the centers of the four sides “not be exposed to the four winds, which could be of much inconvenience.” (Neal Harlow, Maps and Surveys of the Pueblo Lands of Los Angeles, Dawson’s Book Shop, Los Angeles, 1976).

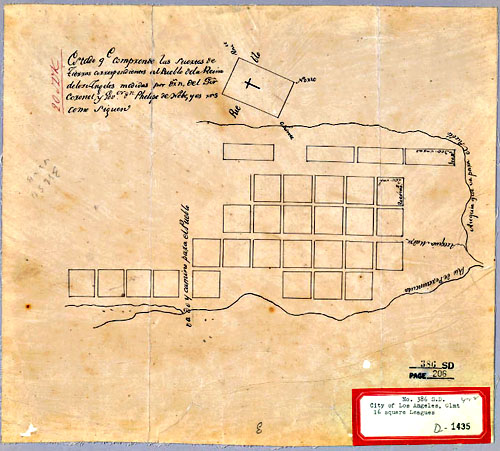

The Harlow Map, 1781. Courtesy of Bancroft Library

That is, Neve wrote a regulation for the two pueblos established in his lifetime that mirrored Ordinance 114. The two pueblos, however, were already laid out when he wrote it. The original Los Angeles pueblo proper already conformed to Ordinance 114 naturally: the ledge it was built on backed against a hill. The base of the hill cut into the ledge and meant the pueblo proper had to be built at an angle to fit on it.

Wind was not a real problem in siting the siting the original Los Angeles pueblo. It is unlikely that Governor Felipe de Neve was seriously concerned with wind when he chose the site of the Los Angeles pueblo.

He ignored other portions. For instance, Ordinance 126, which required that no building lots shall be assigned to private individuals around the plaza; those lots should have been assigned to church buildings and royal houses and were not. Ordinance 124 required a temple built at a distance “so it can be decorated better” and thus acquire more authority. There was no church in the original pueblo. There was a granary and two administrative adobe buildings. The ordinances about slaughterhouses and hospitals had no relevance in the very primitive farming community that started on the banks of the Los Angeles River.

Crouch concluded that the pueblo proper was built at the very site of Yabit (Yang Na), in violation of Law of the Indies Ordinance 38. It was not. Neve followed Ordinance 38 insofar as it could be followed in the Los Angeles basin.

Ordinance 38:

“Once the region, province, county, and land are decided upon by the expert discoverers, select the site to build a town and capital of the province and its subjects, without harm to the Indians for having occupied the area or because they agree to it of good will.”

The principal trading settlement in the area – Yang Na or Yabit – was located near today’s City Hall. Yang-Na’s hunting and gathering territory may have included anywhere the original pueblo could have been established. Other, smaller native villages thrived in the Los Angeles basin. There was no area near the river that was not within some Indian village’s hunting and gathering territory.

Governor de Neve did not violate the spirit of Ordinance 38 if he sited the pueblo to the north of today’s Broadway Bridge, its most likely location. That location was about two miles from Yang Na’s village.

Crouch’s implicit assumption is that the 1781 pueblo proper was located close to today’s plaza, which is close to where Yang Na once was.

It isn’t evident from the text why Crouch came to that conclusion. Perhaps the authors believed the 1825-1830 Olvera Street plaza was the original plaza.

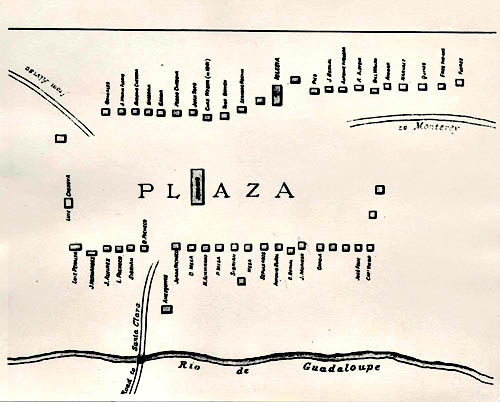

The Coronel Map. Courtesy of Bancroft Library

Antonio Coronel drew a map (the “Coronel map.”) when he was County Assessor in 1854. Crouch turned the Coronel map upside down. (Page 177). The authors erroneously concluded the Coronel map was earlier than the Argüello map.

The Coronel map and a somewhat earlier map, possibly also drawn by Coronel (“the Harlow map”) show allocations of fields above the road that crossed the river (today’s North Broadway). The Argüello map only showed the allocations to those settlers that had arrived in about June 1781. By comparing the maps, it is clear the Coronel map was prepared after the pueblo population had grown and additional land entered cultivation, land in the area designated as “firma para propios” on the Argüello map.

Town planning writing in Alta California that preceded Neve’s regulations for secular pueblos sheds light on the reason Neve created a set of regulations for town planning.

“So far as positive knowledge is concerned, the first action taken by the mother country having direct reference to California was taken on September 10, 1772, when the King issued a series of regulations and instructions for the establishment and government of royal presidios along the northern frontier of his American possessions.” Willoughby Rodman, History of the Bench and Bar of Southern California (William J. Porter, Publisher, Los Angeles 1909), page 9.

These were the Echeveste regulations, which, according to Bancroft, were primarily the work of Father Junipero Serra. Bancroft, History of California, volume 1, p. 333.

The regulations of 1772 stated that the first objective of the royal government was to convert natives. After that, the goal was to gather them in mission towns to civilize them. These objectives – to save the souls of the native people through removing them from their ancient way of life – were not the same as the Crown’s interest.

Spain needed secular pueblos to feed the presidio soldiers and needed the soldiers to fend off claims on California by other countries English flags flew from ships along the Pacific Coast of California beginning in the mid-sixteenth century. Sir Francis Drake had claimed California for England in 1579. Bourbon King Carlos III of Spain believed the English intended to reclaim California. The British not only had 13 colonies on the East Coast but also several islands in the Caribbean and had recently taken Canada from the French.

Russia’s maritime fur trade of mostly sea otter and fur seals pressed down from Alaska. Sea vessels flying the double-headed eagle, the Russian empire’s flag, would twenty years later dominate the Pacific Northwest waters as far south as San Francisco.

Spain’s Law of the Indies, however much Father Serra opposed it, remained in effect until the establishment of Mexico’s independence and, after Mexico adapted the Crown’s rules, until the American conquest. (Rodman, op cit.)

Neve’s town planning regulations, which copied portions of the Law of the Indies, and which King Carlos III approved, implemented the earlier secular law and superseded the Echeveste regulations.

The governor’s regulations served to replace Father Serra’s religious-based town planning with secular planning. King Carlos III approved them.

Early maps show the original plaza, like the Olvera Street plaza laid out almost a half a century later, was cocked at an angle.

In about 1876, historian H. H. Bancroft employed Thomas Savage to copy maps and texts in the provincial archives. Savage was born in Cuba and spoke and wrote Spanish fluently. Thomas Savage wrote, “Report of Labors in Archives and Procuring Material for History of California, 1876-9.” This is collection number BANC MSS C-191 v. 1; BANC MSS C-191 OS Box 1, located at the Bancroft Library. The provincial archives were destroyed in the 1906 fire, so all we have are the copies of documents prepared by Savage and his assistants for H. H. Bancroft.

Bancroft’s collections of historical research survived two fires, including the 1906 fire and sold his library to UC Berkeley. Thomas Savage’s copies of three maps that had been made from the originals that were later destroyed.

The Argüello map may be seen at Title [Puebla de la Reyna de Los Angeles] / Josef Arguello (firmado).Author Arguello, José Dario, 1753-1828. Published [1782], Location Call No. Status

Bancroft BANC MSS C-A 2 AVAILABLE LIB USE ONLY

MANUSCRIPT MAP. Direct Link http://oskicat.berkeley.edu/record=b10795042~S60

Although the library does have this map in with 1782 records, a note next to the map in the physical document says, “sin fecha, sin lugar.”

The Coronel map (turned right-side up) is quite a bit like another map, also at the Bancroft Library but on film, which Neal Harlow reprinted as map 1a in Maps and Surveys of the Pueblo Lands of Los Angeles (Dawson’s Book Shop, 1976, Los Angeles) (the “Harlow map”).

The Harlow map is shelved at the Bancroft in an oversize folder containing “Plano de el Pueblo de la Reyna de Los Angeles,” page 100, shelved in Unit A. Call No. BANC MSS C-A 52-53 FILM. Map 1a corresponds to a sketch made by Thomas Savage or one of his assistants, copied in 1877 from the provincial archives and printed in Bancroft’s California History, volume 1.

Both the Harlow map and the Coronel map were created sometime after the Argüello map. The correct order in time was: 1. The Argüello map; 2. The Harlow map; and 3. The Coronel map.

The Argüello map showed farming lots allocated to nine households, and all of the farm lots lay below the road. The area designated as “firma para propios” or common land was still empty whenever the map was created. Three building sites marked “Y” were empty (There is no name next to the designation “Y,” and no farm lot allocated to “Y.”). That only 9 families received land allocations suggests H. H. Bancroft may have been wrong when he said that Argüello created the map in 1786. Eleven families arrived, in two groups, in 1781. One household, consisting of “Chino” Antonio Miranda of Manila and his daughter, stayed behind in Baja California. Twelve lots would have been allocated in June 1781 for the anticipated twelve families, but three would have remained empty, waiting for the second group to arrive later in the summer, and for Antonio Miranda – who never arrived. This map may have been created as early as June 1781.

The Coronel map, “Land Case Map D-1435,” may be seen on the Bancroft website at http://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/hb7d5nb48n/?brand=oac4&layout=metadata. The writing on the top of this map reads: “Estado que comprende las suertes de tierras correspondientes del pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles [Calif.] : medidas por D~rn. del S[eñ]or. Coronel, y Govorgn. Phelipe de Webs. y es rns. como siguen.”

Antonio Coronel arrived from Mexico with his parents in 1834 when he was seventeen. The Coronel map was used as an exhibit for the city’s claim to Four League’s Square of municipal land pursuant to the 1851 Land Act, created to implement the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. There was no Governor de Webs, only Governor de Neve. The sound of the letter “v” in Spanish is “b.” Neve wrote his first name as Phelipe.

Coronel had several positions in local government. He was both mayor of Los Angeles and County Assessor. The book he painstakingly put together and published in 1854, the Los Angeles Assessor’s Book, 1854, is at California State University, Northridge, Oviatt Library, Special Collections.

The Coronel map and the Harlow map both show the symbol of the cross on top of the pueblo proper. (On one side of the rectangle the map shows the word fragment “Pue,” and on the other side, the maps shows “blo.”)

The Harlow map and the Coronel map both showed four blocks of land below the river. Because there was no scale on either map, it is difficult to estimate how big these blocks were. The Coronel map shows the start (a line) of one block of land and 23 square blocks and four rectangles of land in the “firma para propios.” The Harlow map shows only 22 squares above the road and four rectangles. The 1790 census of Los Angles revealed 24 families lived in the pueblo. These maps were probably therefore created around 1790.

The map created of the by then city of Los Angeles plaza was a survey/map by E.O.C. Ord completed in August 1849. This was a map centered on the new plaza, the rectangle that was very near the present-day Olvera Street marketplace. There is no reference in the Ord survey to the original pueblo proper or to the original plaza. The original plaza is not on the survey at all.

The February 2, 1848, signing in Mexico of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American war. The peace treaty ceded the Mexican territories of Alta California and a large area comprising roughly half of New Mexico, most of Arizona, Nevada, Utah and parts of Wyoming and Colorado.

Beginning on April 3, 1849, General Bennet C. Riley exercised the duties of Provincial Governor during a period of Congressional inaction in making California a state. Riley sent a request during this interregnum to the Ayunamiento (city council) of Los Angeles for a map of the city and information as to titles and the methods of granting city lots.

The Alcalde of Los Angeles informed Riley that there was no map; there had never been one; and there was no surveyor in Los Angeles to make one. There was also no information about titles and as to the methods of granting city lots – that consisted of someone taking a lot, building an adobe, and moving into it.

From the old Los Angeles archives, dated June 9, 1849:

“Resolved: That this honorable body desiring to have this done, requests the Territorial Government to send down a surveyor to do this work, for which he will receive pay out of the municipal funds, and should they not suffice by reason of other demands having to be met, then he can be paid with un-appropriated lands, should the government give its consent.”

Governor Riley sent Lieutenant E.O.C. Ord, of Company F, the Third Artillery, an engineer and surveyor, to Los Angeles.

The center point for the E.O.C. Ord survey of the city of Los Angeles – completed in August 1849 – was the front of La Iglesia de Placita, completed in 1822, which faced the plaza. The artist William R. Hutton – Ord’s partner – did not draw the plaza on the survey; it is shown only as an empty space.

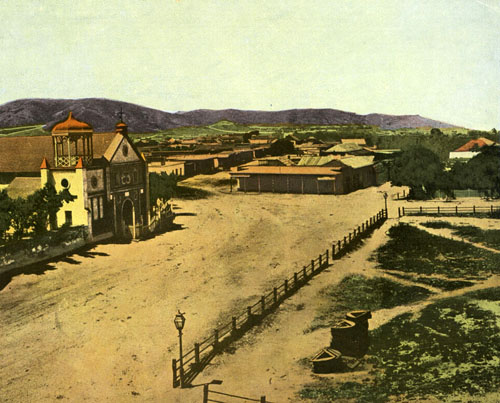

In 1849, the plaza was a rectangle. It had been a rectangle when it was laid out between 1825 and 1830. In an 1869 photograph, it was still a rectangle. By 1873, it was a circle.

Calle Principal and an edge of the plaza in 1869. Courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library

The rectangular plaza was not oriented north to south, east to west; rather, it was built at an angle with its left hand corner pointed north. See, Crouch.

The E.O.C. Ord survey established the streets downtown at an angle that duplicated the angle of the rectangular plaza because Ord and his partner centered the survey at about the front of the church. Until he completed his survey, which was partly a plan for future subdivisions of the municipally owned lands, the roads around the plaza were haphazard, mostly paths between adobe houses, and the houses were built wherever anyone put them.

Until 1849, the boundaries were guesswork: people had just built wherever they wanted after the original pueblo proper was officially established on September 4, 1781. The streets were by and large paths between the adobe residences before 1849.

After, the survey:

“Some residents found their homes standing halfway between two streets because adobes had been built in random locations with haphazard paths leading to them.” Janice Marschner, California A Snapshot in Time 1850, p. 49.(Coleman Ranch Press, Sacramento, CA, Third publication 2002).

It was not until 1828, after Mexico’s revolution, that citizens living in California could acquire absolute title to real property, Rodman, op cit., at page 14. Title to the pueblo’s building lots and agricultural lands remained with the king and reverted to the king if the settlers did not use the land when California was Spain’s. There was, however, no record of any title to land in Los Angeles by the 1830s. Possession was not just 99% of the law; it was all of the law. The Los Angeles cabilido did not plan streets around the plaza; no one planned much of anything. The Ord survey began the governmental process of straightening out streets from the ravel of alleys, as well as recording the prehistoric road (“El Camino Viejo”) and the Toma Road.

Because Ord centered the survey/map at the present plaza instead of at the original plaza in order to determine the four leagues square of municipally owned land, and did not have access to the Coronel or Harlow maps, he did not include the area at the base of the last Elysian Park hill above today’s Broadway Bridge and did not include any area on the east side of the river, which should have been included because the four leagues square should have been measured from the original pueblo proper site.

We cannot see from the Ord survey/map the route that Crespi, probably Anza, and probably Anza took to reach the original site.

The Olvera Street plaza was cocked at an angle because the original plaza sited above today’s Broadway Bridge was cocked at an angle.

Mexican control of Alta California was weak. Nonetheless, the shape, dimensions and orientation of the plaza near today’s Olvera Street corresponded to requirements in Spain’s Law of the Indies. Although Rodman maintains the Law of the Indies applied up to the time of the American conquest, he also remarks elsewhere that the Californios did not feel they needed any legal system and could handle matters without one.

The Cabilido may have followed Neve’s 1782 instruction for the founding of pueblos, even though the pueblo was about 50 years old by that time. Neve’s instruction was likely a political ploy because he had already founded the Los Angeles pueblo proper at an angle.

The angle of the base of the flank of a hill in today’s Elysian Park is probably the primary reason the streets downtown – about 1.5 miles away from that hill – were laid out at an angle rather than from north to south, and east to west.

The angle of that hill in Los Angeles, rather than vigorous conformance to the Law of the Indies is probably responsible for the angle of the downtown streets and for the angle of streets in downtown San Jose and for the angle of two streets in Santa Cruz.

You may see the original site of the pueblo proper if you ride in a car in the passenger seat and drive west across the river over the Broadway Bridge and look down as you pass over the river’s concrete channel. The site is a triangle of land crossed by railroad tracks. If the car driver travels at about 30 mph, you will have about a minute to see it.

Additional sources:

Edwin A. Beilharz, Felipe de Neve, First Governor of California (California Historical Society 1971)

Glen Creason, “CityDig: Map No. 178: The Zanja Madre in 1868.” http://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-map-no-178-the-zanja-madre-in-1868/. (Retrieved 10/30/2016)

Glen Creason, “CityDig: We’ve Hit the Mother Ditch,” April 24, 2014, Los Angeles Magazine. http://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/citydig-weve-hit-the-mother-ditch/. (Retrieved 10/30/2016).

Crouch, Garr and Mundigo, Spanish City Planning in North America (The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London, England, 1982).

Mark J. Denger, California Center for Military History, “The Two Forts of Fort Hill: The Siege of Los Angeles and Fort Moore.” https://web.archive.org/web/20070208184315/http://www.militarymuseum.org/FtMoore2.html. (Retrieved 10/17/2016)

Mark J. Denger and Charles R. Cresap, California Center for Military History, “Californians and the Military: Major General Edward Otho Cresap Ord.” http://www.militarymuseum.org/Ord.html. (Retrieved 10/12/2016)

William David Estrada, The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space (University of Texas Press 2008)

James Miller Guinn, Historical and Biographical Record of Southern California (Chicago, Chapman Publishing Co. 1902),

- M. Guinn’s conviction that the original plaza was located a little uphill of the Olvera Street plaza was based on his belief that there was a barracks in the original pueblo and that its location had been very near the Olvera Street plaza. See, for example, “Historic Houses of Los Angeles,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, Vol. 3, No. 4 (1896), pages 62-69).

James Miller Guinn, “The Passing of Our Historic Street Names,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Vol. 9. No. 1-2 (1912-1913), pp. 59-64. Guinn was often incorrect in his conclusions. He contended, in this essay, that Governor de Neve created Calle Principal. Calle Principal did not exist until the plaza existed between 1825 and 1830. Felipe de Neve died in 1784.

Blake Gumprecht, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death and Possible Rebirth (John Hopkins University Press, 1st Paper Back Edition (2001).

- M. Guinn, “The Plan of Old Los Angeles and the Story of its Highways and Byways,” Historical Society of Southern California Annual Publication, volume 3, 1893-96.

Carla Hall, “Leave the Zanja Madre – the ‘Mother Ditch’ – in the Ground in Chinatown.” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 2014.

Neal Harlow, Maps and Surveys of the Pueblo Lands of Los Angeles, (Dawson’s Book Shop, Los Angeles, 1976)

Owen Jarus, “Early Urban Planning: Ancient Mayan City Built on Grid,” LifeScience, April 29, 2015. http://www.livescience.com/50659-early-mayan-city-mapped.html. (Retrieved 10/6/2016)

- Gregg Layne, “Edward Otho Cresap Ord: Soldier and Surveyor,” Quarterly Publication (Historical Society of Southern California) Vol. 17, No. 4 (December 1935), pp. 139-142.

William M. Mason, Los Angeles Under the Spanish Flag (Southern California Genealogical Society, Inc. Burbank, California 2004)

Nathan Masters, “Why L.A. Has Clashing Street Grids,” KCET, Lost L.A., January 25, 2012.

https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/why-la-has-clashing-street-grids. (Retrieved 10/16/2016)

Nathan Masters, “The Lost Hills of Downtown Los Angeles,” KCET, Lost L.A., October 13, 2011. https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/the-lost-hills-of-downtown-los-angeles. (Retrieved 10/20/2016).

Zelia Nuttall, “Royal Ordinances Concerning the Laying Out of New Towns,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 1922), pp. 249-254, published by Duke University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2506027.pdf. (Retrieved 10/6/2016. Original access: 08-10-2016).

Edward Otho Cresap Ord Papers, 1850-1883. Bancroft Library, BANK MSS C-B 479.

Donald B. Robertson, Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History: California, (Caxton Press, First edition, 1998), page 139.

The Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles, “Historical Perspective.” http://www.lacourt.org/generalinfo/aboutthecourt/GI_AC004.aspx. (Retrieved 10/16/2016)

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.