Honey Reveals The Truth About Little Red Riding Hood

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste.) Honey van Blossom

I will tell you the true story of Little Red Riding Hood.

The true story isn’t about our fear of wildness or our fear of sexuality — although it could have been that story and perhaps that’s the story behind the red cloak: red as in blood, the danger if nature, or blood as in menstrual blood. Little Red Riding Hood was not a child but menstruating.

The “Little” part comes from a mistranslation from the original in the Dutch Roodkapje. In Dutch, tje/pje/kje/je/etje..etc, are suffixes added to nouns/adjectives/adverbs, to make something sound small or to show intimacy. That suffix is called the diminutive. Roodkapje meant something like, “Dear” Red Hood.

“Kap” means a hood worn over the head and shoulders when used as a noun. The woman, whoever she was, wore a red hood over her head. Moreover, there is no “riding” in Roodkapje. I couldn’t locate in a dictionary or on-line Internet search a thing called a “riding hood” except if the reference is to a “little red riding hood.”

If the story originated in German – but it may have originated elsewhere — the linguistic analysis is almost the same. The young woman wore a dear red hat to show she was available to the right wolf. It was a signal to him.

In one interpretation, Red Riding Hood is a parable of sexual maturity. In this interpretation, the red cloak symbolizes the blood of the menstrual cycle. In one fairy tale version, the wolf threatens the girl’s virginity. The wolf symbolizes a man, who could be a lover, seducer or sexual predator.

Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1922 version, page 774) uses the Red Riding Hood story to suggest the link between fairy tales and our primitive past. In more modern times, Katherine Mansfield retold the story in “The Little Governess,” and before that Charlotte Bronte retold the story in Jane Eyre: Mr. Rochester is the wolf, and he keeps the wife he’s driven mad in his attic. Jane tames him only after he’s blinded in the fire that kills his mad wife. Weakened, he needs her, and so her passion for him no longer puts her in danger.

The false stories about the wolf pose him, first, as male, and then they also describe him as ravenous — and the true wolf was indeed those things, or at least, sometimes these things, except this wolf, the wolf in the real story, was ravenous for experience. Full of joy, apparently nonchalant but not, what he wanted to know was everything. He, like the pagan, the Mayan, the European wolf — the wolf all women long for but who can consume them unless they can weaken him – had an appalling lack of humor. Wolves are not funny. Coyotes yes. Dogs often. Wolves no.

The true story is this.

They were all liars in that village. They played easy listening music on the radio that made them crazy because it spun a myth of safety, and no one is safe. The villagers said they believed they would be resurrected after death if they worked in their dreary jobs that were without grace and obeyed the municipal laws and they violated the municipal laws. They complained about taxes that gave money to the poor, the sick and the disabled, although they were often poor, sick and disabled. They eschewed cooperation but believed that competition and consumption were key to moral life. They believed things were always the same.

The grandmother had been baking sugar cookies for the wolf and putting them into the fruitcake tin to keep them fresh when her daughter and son-in-law came home unexpectedly and the wolf didn’t know what to do and ran around and hoped into bed and covered himself with blankets and the grandmother joined him, which looked very out of the ordinary to her family when they opened the bedroom door, so they lied and said the wolf ate the grandmother.

He was a vulnerable animal — as tender as the first spring mallow — and his eyes were light green in the sunlight and only profound and brown in shadow but he was often in shadow because he was, after all is said and done, a wolf.

The false story paints Little Red Riding Hood as an innocent, because the liars in the village wanted to see her as a virgin. She was in the true story innocent but not in their sense. In the extraordinary sense, which is the true version of the story, her innocence lay in knowing the lies in the village were lies: our only responsibility is to be kind because we all die, work must be joyous for the same reason, and law is unnecessary if we are free.

Because she was young, Little Red Riding Hood had no pity. It took years for her to look back at the village she came from and the harrowing winters and to think, “I miss them.” but by then it was too late.

She saw the wolf in the forest. She spun the wool. She dyed it red with Cochineal — cactus berries concentrated when female beetles eat them. She knitted her dear red hat. So maybe the forest itself was a lie, and the first red riding hood story began in Mexico, although I think the wolf lived in Los Angeles where the Cochineal cacti grow along the old red car easement.

One day, in late afternoon, the wolf burst from the forest and ran along its edge. The light burnished his fur. He was glorious.

She threw on her hat and ran on four feet to the wolf and ran alongside him. Her cloak fell from her shoulders. She was naked and sleek as she raced the sinuous light towards the end of day.

The primeval wolf and primeval woman went fast across miles of land with no farms on them, the primordial land, rich and warm under their feet, “Take me,” said the wolf. She did.

The wolf and the woman changed because everything does all of the time and also because during the moment of their mating that seemed to them as if it went on forever they knew they were both helpless.

When she was an old woman, she walked to the edge of the field, where the tents stood. These were the tents were she stored memories.

It was early spring, and an oriole sung in a nearby tree. A duck out on the lake called. When she first built the tents, there had been doves. She used to lie in her bed in the morning and look at the mountains,, and that was the first thing she heard: the doves.

In the first tent she kept things from her village, where she had lived with the liars. There was a yellow ceramic rooster with holes on its head for salt, a brush with soft bristles that had a silver back inscribed with her grandmother’s maiden name, and a jar of dried lilac, a Frank Sinatra song.

She went to the tent of her school and there was the carpet she saw in art class when she was fifteen – a completely imagined carpet but one so precisely woven she counted the threads that made up the field of tulip, hyacinth, carnation, and rose, bordered with animations of the wolf – that told her the future ahead of her.

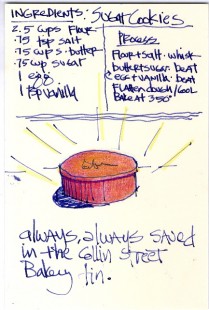

The things inside the wolf’s tent were spare. There were delicate fish bones, small and medium-sized mammal bones, and the lemon sugar cookies the grandmother made rested inside of a yellow fruitcake tin. The lemon rind made all the difference. The wolf had been unable to resist them. They were not good for him and made him fat and they reminded him of love.

(The grandmother’s recipe for sugar cookies follows but his mother forgot to write down about the lemon rind.)

Image courtesy of Rhett Beavers (2010)