Honey on the road to San Francisco with some of the Spanish explorers

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

“Cities of the Golden Gate,” Raymond Dabb Yelland, 1893. Most illustrations can be enlarged by clicking on them.

Prologue to the story of the Spanish exploration and settlement of California

Seasonal migrations of animals now extinct in California probably created the roads the native people used before the Spanish land exploration of California.

“The heyday of giant mammals in North America was the middle and late Pleistocene, an epoch that started 2.6 million years ago and ended 11,700 years ago, around the time the Earth was thawing out from the Ice Age. The gigantic beasts, which migrated from Asia across a now-vanished land bridge called Beringia, are known as Rancholabrean megafauna, after the famous La Brea tar pits in downtown Los Angeles — the graveyard of thousands of saber-toothed tigers, giant bison and other extinct animals.”[1]

The seasonal migrations of the large mammals may have created the substantial roads used by the indigenous people after their arrival.[2]

Paul S. Martin and Richard G. Klein argue that Paleoindian over-hunting led to the extinction of the megafauna.[3] Others argue that climate change was responsible for mammoth and mastodon extinctions. As the last major glaciation ended around 12,000 years ago, climate warmed too quickly for the megafauna to adapt.

Whichever theory is correct, no one disputes that Paleoindians in California hunted the large beasts. This meant they followed the large animals until they became extinct.

John Muir pointed out that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” The extinction of camels, horses, buffalo and the megafauna in California by about 11,000 years ago meant a different natural landscape from the ones the Indians inherited when they migrated into the area at least 15,000 years ago.

The roads created by large animals survived to support an extensive trade system before the Spanish arrived. These roads made the Spanish explorers’ journeys possible. The roads made it possible for the padres to establish the missions.

The roads the native people followed – howsoever those roads were created — may be discerned faintly in today’s palimpsest. Bernice Eastman Johnston’s California Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum, Highland Park, 1962) contains a map of Indian routes through Los Angeles, but these routes are partial: Indian routes were everywhere. Johnston does show the road that became known El Camino Viejo, the ancient road that appears in E.O.C. Ord’s 1849 La Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles. The road from the San Gabriel Mission area is designated on the map in the Johnston book as a straight line, rather, as two parallel straight lines.

La Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles was the first map and survey of Los Angeles, created thirteen years after the remnant population of the primary village in Los Angeles – Yang-Na – was evicted. It shows the same road – El Camino Viejo — with three branches that left the 1849 plaza area (formerly Yang-Na) at the location about where City Hall is today. One branch went to Santa Monica. Very roughly, that is today’s Wilshire Boulevard. One branch went towards the Cahuenga Pass and probably existed in 1850 – probably later, but it is not evident on either the Ord map or subsequent maps. The road to the mission is not evident on the Ord map.

The branch of El Camino Viejo that went east and then north is abruptly abandoned on the Ord map. It is difficult to discern it today but it is roughly Glendale Boulevard to Echo Park Lake, also not on the Ord map, although it should have been.

That easterly road may have been the connection with the road that went through what became the Feliz Rancho to the road in the Central Valley known later as El Camino Viejo a Los Angeles. That road ended at today’s Lake Merritt.

An ancient predecessor road probably is more or less today’s Ventura Boulevard. Highway 1 and the 101 freeway – after it leaves Ventura — probably followed ancient routes. First Street in San Jose becomes Monterey Road, which leads to Monterey. San Pablo Avenue in Contra Costa County probably started as an Indian road. Anza traveled through today’s Concord on today’s Willow Pass Road towards today’s Antioch. Fages traveled to Mt. Diablo along a road that is today more or less the 680.

Tracing roads the Spanish explorers followed from Los Angeles to the Bay area is a portal into the hunter-gatherer landscape of the indigenous people. Traveling with the Spanish explorers also partially reveals the American-era transformations of the landscapes, the obliteration of the native presence in Los Angeles and the misconceptions of early Spanish Colonial history because of American era biases.

Spain had no more legitimate claim to California than did any other European country. It was a country that looked backward by 1769, oblivious to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England and — while not blind to the Age of Enlightenment — nonetheless predicated its settlements in California on a feudalistic land ownership scheme tied to religion, a religion that still prosecuted in the New World what it believed was witchcraft, but which was actually the prosecution through inquisition of native beliefs.

Spanish discovery of the Golden Gate

Raymond Dabb Yelland’s 1893 painting “Cities of the Golden Gate” shows a perspective of the San Francisco Bay seen from a hill above Oakland. The time of day was afternoon. The small body of water in the middle ground was Lake Merritt, which then still joined San Antonio Creek.

The lake had been an arm of the San Francisco Bay formed where several creeks emptied into the bay.

“Framed by thousands of acres of surrounding tidal marsh, the slough occupied 500 watery acres at high tide and 375 acres of mudflats when the tide was low. Alder, sycamore, live oaks, and California bays lined the banks of the streams that emptied into it. Herds of deer, elk, and pronghorn antelopes grazed the grasslands around it. Foxes, bobcats, coyotes, and mountain lions prowled the hills above it; countless numbers of ducks and geese touched down upon its inlets and channels—the skies were dark with them.”[4]

By 1810, the Native Americans that had lived there had been relocated to the Mission San Jose. By 1820, the slough was part of the land grant to Sergeant Luis Maria Peralta. The Peralta were among the settlers with the 1776 Juan Bautista de Anza expedition. This group of settlers founded the San Francisco Presidio, Mission Santa Clara, and San Jose.

In 1868, Dr. Samuel Merritt, a mayor of Oakland proposed a dam between the estuary and the bay. The projects took until 1875 to complete.

The long piers extending into the Bay were the S.P.P.R. Narrow Gauge and the Oakland Mole. The Oakland Mole pointed at what was called at the time Goat Island, now called Treasure Island.

If the woman in the white dress were to turn around to face the Bay, she could not see the Golden Gate, the strait that is the entrance to the Bay from the Pacific Ocean. She could see the San Pablo Strait, which leads to San Pablo Bay.[5]

To see the Golden Gate, the woman would have had to walk north and northwest to reach to a hill that faced the Golden Gate without obstruction.

Below is a “Bird’s Eye” map of Oakland in 1900, created in 1899 by Fred Soderberg.

Clicking on the maps expands them. For a version of the closeup map that can be scrolled: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364o.pm000300. (Retrieved 12/1/2018)

From the Bird’s Eye map, it looks like it was possible to see the Golden Gate from the shore, perhaps from the site of the factories shown at the edge of the Bay.

In 1770 – 123 years before Yelland painted “Cities of the Golden Gate” — four soldiers left the Pedro Fages expedition campsite and traveled a long distance on horseback, returning to the camp at night. They were the first non-indigenous people to see the entrance from the Pacific Ocean to the San Francisco Bay. No one today knows where they rode to see the Golden Gate. Stanger and Brown, cited below, believed the soldiers saw it from the hills above Oakland.

Spanish ships did not see the entrance to the Bay from the Pacific Ocean for centuries, even though they sailed near it.

Frank M. Stanger and Alan K. Brown’s book Who Discovered the Golden Gate?[6] begins with a sketch of the Fallaron Islands seen from the ocean.

The Fallaron Islands or Fallarones (from the Spanish farallón meaning “pillar” or “sea cliff”) are a group of islands and sea stacks twenty-seven miles from the Golden Gate Bridge. Wind and water carved these cliffs and granitic spires.

Sir Francis Drake discovered the Fallarones in 1595, and Basque soldier, entrepreneur, and explorer navigator Sebastián Vizcaíno (1548-1624) charted them in 1603.

Dangerous shoals surround the Fallarones and the risks of navigating near them led to the late discovery of the Golden Gate.[7]

The Fallaron Islands camouflaged the passage into the San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean. Historians Rawls and Bean[8] add heavy fog and the fact that the Berkeley Hills, Alcatraz and Angel’s Island appear from a distance to comprise one shoreline to the reasons early navigators missed seeing the entrance to the Bay.

Who Discovered the Golden Gate? briefly mentions the possibility that Sir Francis Drake entered the Bay but Stanger and Brown find the evidence of Drake’s entry into the Bay thin. H. H. Bancroft in his History of California, weighed the different historical perspectives and determined Drake did not enter the San Francisco Bay.[9]

If Drake did enter the San Francisco Bay that knowledge was lost by the time Spanish land explorers saw the Bay.

Spain commissioned Portuguese-born Sebastián Rodríguez Cermeño

to establish a safe port on the Manila-Acapulco route, Cermeño landed his ship the San Agustin in present-day Drake’s Bay in 1595.

While Cermeño and part of his crew explored the surrounding region, a winter storm sunk their ship. Between seven and twelve men died and all goods – mostly silk, wax and porcelain – were lost. Cermeño named Drake’s Bay “La Bahia de San Francisco” after St. Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscan order.

The navigator and his crew of 80 men eventually made it back to Acapulco on a small launch that had been brought from the Philippines.

Cermeño failed to notice the entrance to today’s San Francisco Bay.

Stanger and Brown concluded that members of the first land expedition — the 1769 Gaspar de Portolá expedition — were the first non-Indians to see the Bay but did not see the Golden Gate.

A small part of the Portolá expedition discovered the strait — led by the expedition’s chief scout José Francisco Ortega — on November 1, 1769, purportedly from a high point on Sweeney Ridge near Pacifica and west of the San Francisco International Airport. That is, Ortega and his companion soldiers stood on a hill above the western side of the San Francisco Bay.

Portolá thought it was a tributary to Cermeño’s bay and called it the Estuary of the Bay of San Francisco.[10]

Discovery of Monterey Bay

The discovery of Monterey Bay preceded the discovery of the San Francisco Bay by 167 years.

Sebastián Vizcaíno (1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat. In 1601, the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico, the Conde de Monterrey, appointed Vizcaíno to locate safe harbors in Alta California for Spanish galleons to use on their return voyage from Manila to Spain. Vizcaíno was also to map in detail the coastline that Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo had first reconnoitered sixty years earlier.

Vizcaíno left Acapulco with three ships on May 5, 1602. On November 10, 1602, Vizcaíno entered and named San Diego Bay. Sailing up the coast, he named the Santa Barbara islands, Point Conception, the Santa Lucia Mountains and the bay he named Monterrey.

Vizcaíno’s ships entered the Monterey Bay on December 16, 1602.

Vizcaíno wrote:

“….The general, commissary, admiral, captains, ensign, and the rest of the men landed at once; and mass having been said and the day having cleared, there having been much fog, we found ourselves to be in the best port that could be desired, for being sheltered from all the winds, it has many pines for masts and yards, and live oaks and white oaks, and water in great quantity, all near the shore. The land is fertile, with a climate and soil like those of Castile; there is much wild game, such as harts, like young bulls, deer, buffalo,[11] very large bears, rabbits, hares, and many other animals and many game birds, such as geese, partridges, quail, crane, ducks, vultures, and many other kinds of birds which I will not mention lest it be wearisome. The land is thickly populated with numberless Indians, of whom a great many came several times to our camp. They appeared to be a gentle and peaceable people. They said by signs that inland there are many settlements. The food that these Indians most commonly eat, besides fish and crustaceans, consists of acorns and another nut larger than a chestnut.[12] This is what we were able to understand from them.”[13]

Vizcaíno’s description led to a flurry of interest in establishing a Spanish settlement at Monterey. The last proposed expedition was delayed and then cancelled in 1608.[14]

Monterey was to become the capitol of Baja and Alta California in 1776. This same year, Captain Juan Bautista de Anza arrived with the first settlers for Spanish California. Monterey was to be a stopping place for the San Francisco settlers as well as a presidio, where some of the settlers remained.

Reasons for the land expeditions to California

A frequent explanation of the reasons for the Spanish Crown to develop Alta California in 1769 — 161 years after the previous proposed expedition — was to protect a Spanish borderland from Russian or English intrusion.

There was not, however, any imminent threat from Russia or England in 1769, when Spain’s first exploration of California by land took place. Not until a little later did France, Russia, America and England show an interest.

Louis XVI of France sent Jean François de Galaup, Comte de Lapérouse to present-day California in 1786 as part of a voyage of discovery that explored both the north and south Pacific. Lapérouse stopped at the Presidio of San Francisco long enough to create an outline map of the Bay. Ships arrived from the New England states as early as 1787 for the sea otter trade.

George Vancouver’s exploration of the California coast in 1792—16 years later — did not lead to an invasion.

In about 1806 – 30 years later — the Russian-American Company’s director Nikolai Rezanov recommended that a settlement be established in California.

By about 1825, French, Russian, American and English fur hunters arrived on the California coast.

The roles of José de Gálvez y Gallardo and Father Junípero Serra y Ferrer in Spain’s decision to colonize Alta California

An explanation for the rumors about imminent English or Russian invasion begins with José de Gálvez y Gallardo, marqués de Sonora, Vistador of New Spain.

In 1769 Gálvez proposed consolidating and developing the far northwestern portion of the Empire – including undeveloped Alta California — under a huge governmental unit. According to historians John Rawls and Walton Bean, Gálvez spread gossip about imminent invasion by Russia.[15] .

Rawls and Bean attribute Spain’s expansion into Alta California to Gálvez’s intense personal ambitions. “…Although he was a brilliant, forceful, and generally successful administrator,” they wrote, “he was also unusually vain, selfish, ruthless, deceitful and unstable. It was, indeed, because of Gálvez’s possession of this very combination of qualities that the occupation of San Diego and Monterey, long considered and periodically given up as hopeless, actually materialized.”

Walton and Bean also documented that Gálvez once had a complete mental breakdown, and – on another occasion — that he planned to dress Guatemalan apes as soldiers to fight the Yuma Indians. There were no apes in Guatemala.

Gálvez prepared a series of expeditions of soldiers, artisans, Christian Indians and missionaries to push north into Alta California. He assigned Father Junípero Serra y Ferrer (1713-1784 — born Miguel José Serra Ferrer in Majorca) to head the missionary team into Alta California. Father Serra – eager to evangelize the Indians in Alta California – readily accepted.[16][17]

Santa Clara University professors Beebe and Senkewicz reveal the conflicts between Spanish secular and Franciscan religious objectives.

“ Junípero Serra was an eighteenth-century man whose fundamental angle of vision pointed toward the past.” [18] That is, Serra’s education and experience led him to look back at sixteenth century Spanish and colonial political models.

In the seventeenth century, on the other side of the continent Puritan minister Roger Williams (1603 to 1683) said that “Forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils.” He also said that (it is) against the testimony of Christ Jesus for the civil state to impose upon the souls of the people a religion. Jesus never called for the sword of steel to help the sword of spirit.” Williams was arrested and convicted of heresy and sedition, but the concept of separation of church and state became more common during the eighteenth century, promoted by the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment.

Beebe and Senkewicz also pointed out:

“The major social role the missions played was to train the indigenous people who managed to survive to be experienced and knowledgeable ranch hands.”[19] That had not been Serra’s objective in joining the expedition in 1769. His goal had been to save “the gentiles” from their native beliefs – about which he knew nothing – and to turn them into Catholic communicants. The mission system depended on agriculture. Agriculture required laborers, and the primary labor force was the native people.

The first governor of California that was not a military commander – Felipe de Neve – believed that the Indians did not need to be forcibly conscripted into the mission system. They would eventually become Catholic congregants, he felt. Inasmuch as the Los Angeles archives show that the non-native California Indian people excluded the Indians from attending mass on the ground they were dirty, he was probably correct.

Gálvez established a naval base at San Blas and, in 1768-1769, organized sea and land expeditions up the California coast to the projected Spanish outpost at the harbor named Monterrey by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602.[20]

The 1769 Portolá land expedition

The 1769 Portolá land expedition began in Loreto in Baja California. Five groups departed from Baja California and headed north for San Diego. Three groups traveled by sea while two others traveled by land with mule trains. Captain Fernando Rivera, moving north through Baja California, gathered horses and mules from the Catholic missions to supply his overland expedition.

The San Antonio arrived at San Diego on April 11th, and the San Carlos arrived on April 29th. Many of the crewmembers on both ships had fallen ill during the voyage, mostly from scurvy.

The crewmembers set up camp on the beach, surrounding it with an earthen parapet with two cannons mounted. From their ships’ sails and awnings they made two large hospital tents, as well as tents for the officers and priests. They gathered herbs hoping to save the sick men.

Two or three men died every day until the entire sea expedition shrunk from 90 to eight soldiers and eight sailors.[21]

Rivera’s column arrived on May 14. They built a camp on a hill now known as Old Town. They erected a stockade on land that later became the Presidio of San Diego.

Portolá led the second land group, which set out from Loreto. Father Serra joined this party as chaplain and diarist. Father Serra suffered a chronic infection of his left foot and leg and stayed behind, eventually catching up on a mule.

The San Carlos lost all of the ship’s officers, the boatswain, the launch coxswain and the storekeeper. Portolá placed all the remaining seamen on the San Antonio, which returned to San Blas.

After two weeks of recuperation, Portolá resumed the northward march to rediscover the port of Sebastián Vizcaíno had proposed – Monterey – 167 years before.

On that journey, Portolá left the campsite vaguely identified today as west of Alhambra on August 2, 1769. The explorer described the road they followed as “a good road.”

The next campsite was on the eastern side of the Los Angeles River at about the location of the Downey Recreation Center. On August 3rd, the expedition crossed the river at the place where the Broadway Bridge now spans the river.

They traveled a half league – 1.8 miles – and met the Indians of Yang-Na “on the road.”

The road they followed from the place they crossed the river was about where Baker Street is today, skirted the river, and went that half league along the continuation of the Indian crossing road later called “Toma Street.” The American-era city reconfigured Toma Street but its successor today is North Main Street or North Spring Street.

That road – the largest part of which was called Toma Street by the middle 1800s — brought the expedition to where City Hall stands today, then part of the native village of Yang-Na. That block was reconfigured in 1928.

The road became a road with three branches, called later El Camino Viejo. The expedition followed the branch that went west past the La Brea tar pits to Santa Monica. They could not find a way from Santa Monica over the mountains and doubled back, purportedly going over the Sepulveda Pass.[22]

On their return trip in January 1770, the expedition went over the Cahuenga Pass, possibly following a portion of the road that was to eventually become Sunset Boulevard, and probably joined the second branch of El Camino Viejo to enter Yang-Na and from there to the crossing place at the bottom of the Glendale Narrows.

The journey had been arduous, and they had resorted to eating their mules. Portolá wrote they returned to San Diego reeking of mule.

When Portolá returned to Mexico City in 1770, he urged that – if the Russians wanted Alta California, which he doubted – they should have it.

The 1770 Pedro Fages expedition from Monterey

Beginning on November 21,1770, Pedro Fages led an expedition from Monterey to the San Francisco Bay.[23] The expedition traveled 26 leagues (93.6 miles) to the bottom of what Fages called the estuary. From the Monterey Presidio to the bottom of the Bay is 80.2 miles using today’s roads, but he could have been as far as Milpitas.

Fages may have traveled as many leagues as he wrote that he had, or he may have estimated the distance by the number of hours traveled. If he was accurate in his distance estimate, he could have reached Fremont, although Fremont is not at the bottom of the Bay.

On November 28th:

“Four soldiers set out to explore the country and at night returned saying that they had traveled seven leagues (25.2 miles) to the north; that the country was good and level; that they had climbed to the top of a hill but had not been able to see to the end of an estuary which communicated with the one which lay at our left; …. They said, also that they had seen the mouth of the estuary, which they thought to be the one; which entered through the port of San Francisco.[24] This I confirm through having seen it.”[25]

If the soldiers traveled 25.2 miles north from Milpitas, they reached Castro Valley, which would not have given them a view of the Golden Gate.

If the soldiers traveled 25.2 miles from Fremont and had gone north and northeast into the hills, they would have been at the site of today’s Chabot Space and Science Center. It is possible to see the Golden Gate from a little above that point.

Stanger and Brown believed the soldiers’ vantage point was above Oakland.[26]

The place from which the unknown soldiers saw the Golden Gate depended largely on what Indian road led to that place. The road had to have been wide enough to accommodate at least four horses.

Horses, camels and other – including bigger – animals became extinct by about 12,000 years ago in California, roughly coincident with the arrival of human beings. Excavations at the Caldecott Tunnel (On the 24 freeway, five miles north of the Chabot Space and Science Center) unearthed two vertebrae of a Miocene camel species, the metatarsal bone of an ancient horse and other fossils. It is possible the first Indians in California followed the animal trails into the hills, and that they continued to use those roads after the extinctions up until 1772.

A better perspective of the Golden Gate would have been from the Berkeley hills. If you walk up towards the Lawrence Hall of Science and walk up the fire road through Strawberry Creek Canyon along the side of the hill, there is an unobstructed view of the Golden Gate – but then the distance calculations would be off.

The Fages expedition returned started their return trip on November 29. To have traveled as far as the soldiers say they did and returned sometime in the night, they had to have traveled for fourteen hours at a good clip – the horses running through part of the trip – without rest. The sun set on November 28, 1770 at 4:57 p.m. The sun rose at 7:10 a.m. They rode for at least four hours in darkness. If the scouting expedition traveled as far as Fages reported, it was impossible that Fages went to the location to travel up the hill to see the bay, so he could not have confirmed it “through having seen it” in 1770. Fages returned, however, in 1772, and this has to be when he saw the strait.

Rivera and Serra – 1773

Fernando Javier Rivera y Moncada led a small expedition to what would be San Francisco at the end of 1773. The members of this party became the first Europeans to walk the shores of what would be called the Golden Gate. Rivera believed the bleak, rainy Peninsula was a worthless site for settlement and wrote this to the Viceroy in Mexico.

Father Serra wished to establish a presidio and mission at the northern end of the San Francisco peninsula. Rivera was opposed to building more missions on the ground there were too few soldiers in Alta California to protect them, but he ultimately acceded to Serra’s wishes and explored the San Francisco Bay area in 1774.

The 1775-1776 San Francisco colonists led by Juan Bautista de Anza

Fog, storms, rocks along the coast, and scurvy made the sea route to Alta California perilous. To adequately populate what would become this Spanish Borderland to protect it from the possibility of foreign invasion, a land route from Mexico needed to be opened.

Juan Bautista de Anza was born in Fronteras, New Navarre (today Sonora, Mexico) near Arizpe in 1836. His family — on both sides — were military families. His Basque father Juan Bautista de Anza 1 had dreamed of being the one to open the land route. He died when Anza was three years old.

Anza had not been ordered to explore a land route: he asked to be the one to do it. He had to have known he might not have returned to his family. Apaches had killed Anza 1. He had to have known he was taking on a difficult, possibly quixotic responsibility.

On January 8, 1774, Anza set out from Tubac, near today’s Tucson, Arizona, with 3 padres, 20, soldiers, 11 servants, 35 mules, 65 cattle and 140 horses for Monterey. Anza recruited an Indian, Sebastian Tarabal – Tarabal had escaped from the San Gabriel Mission — to guide them along a southern route along the Rio Altar, and then they paralleled the modern Mexican border, crossing the Colorado River at its confluence with the Gila River, in the territory of the Yuma Indians. This expedition arrived at the San Gabriel Mission on March 22, 1774. They reached on April 19th.

Anza returned to Tubac – near Tucson, Arizona — by late May 1774. On October 2, 1774, the Spanish government promoted him to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and he was ordered to lead colonists through the land route from Mexico to Monterey. He also received an assignment to survey the area of San Francisco Bay for a favorable location for a presidio.[27]

The explanation for Anza’s second (1775-1776) journey is that he was ordered to take colonists to Monterey, and he was ordered to survey the area for a presidio.

Anza’s second expedition left El Real Presidio de San Miguel de Horcasitas in the center of the province of Sonora on September 29, 1775. He recruited the settlers from among the poorest people living in northern New Spain. The expedition’s diarist Father Font counted 240 people, including settlers, soldiers, the leaders, at least three Indian interpreters, vaqueros and muleteers. In a similar list, Anza counted 191 people left Tubac.[28] Over 1,000 animals came with them.[29]

The road through the desert was grueling and dangerous. Seventy-three years after the second expedition, a gold-seeker that followed the desert route wrote, “”Until one has crossed a barren desert, without food or water, under a burning tropical sun, at three miles an hour, one can form no conception of what misery is.” [30]

Vladimir Guerrero’s The Anza Trail describes both of Anza’s harrowing journeys through the desert to reach the San Gabriel Mission.[31] The winter journeys were also perilous and difficult.[32]

The 1775-1776 Anza expedition arrived in what is now Yuma, Arizona on November 15, 1775. They crossed the Colorado River with the assistance of the Yuma chief, Salvador Palma. They then passed through the Borrego Springs area of California, where they endured the coldest winter ever recorded.

On this journey, the Anza expedition passed through the shifting sandy wastelands west of Yuma. After they reached the haven of Sebastian (Harper’s Well) on December 18, dry camps alternated with wet camps. At a dry camp, thirsty cattle stampeded, and most were not recovered.

Anza reached the San Gabriel Mission on January 4, 1776. The mission could not support the expedition for long, and for a period, the members of the expedition went hungry. One soldier and several muleteers escaped, taking with them many of the horses.

I found no sketch or painting of the Mission San Gabriel before the current structure was built in about 1805. In 1776, the mission buildings were built of sticks and thatch. I substitute John Sykes sketch of the Carmel mission in 1794 to suggest what the Mission San Gabriel may have looked like in 1776.[33]

Anza and about two-thirds of the colonists and soldiers left the mission at 11:30 a.m. on February 21, 1776, and they traveled on the roads the expedition’s diarist Father Pedro Font described as “miry.” The roads in Southern California during the Spanish Colonial era were notoriously difficult in winter. Felipe de Neve called them impassable during the rainy season. The expedition’s mules were stuck in mud and slowed down travel.

Both Font and Anza described their journey from the Mission San Gabriel to the Los Angeles River as “two leagues.” This may be an estimate based on the time it took them to reach the crossing place – the area of river now spanned by the Broadway Bridge – rather than an exact measurement. An horse generally rode “one league” in one hour. A league was also 3.6 miles. The distance from the mission to the crossing place on today’s roads is closer to eight or nine miles, depending on the road.

Neither Font nor Anza described the river crossing. Inasmuch as the expedition crossed at the bottom of the Glendale Narrows – most likely at the same crossing place as the Portolá expedition had crossed the river — in February, it could have taken some time for all of the soldiers, settlers, muleteers and Indian guides to get through to the western bank.

They arrived by dusk at a place they called El Portezuelo after having traveled a total of what both Anza and Font said was five leagues. Sunset was at about 5:30 on February 21, 1776, and – according to Father Font – they had traveled five and a half hours.

The term “El Portezuelo” is – and was in 1776 – an archaic Latinized Spanish meaning the door. The “zuelo” part of the word could be derogatory or affectionate or could mean “little.”

The road from the place they crossed the river to the western bank is more or less North Spring Street. The native village of Yang-Na they had to have passed through is occupied by El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, City Hall and the front of Union Station.

It is not possible to follow Anza’s trail except very roughly through downtown Los Angeles because the 1776 landscape was obliterated.

Southern Pacific Railway occupied the land below the Broadway Bridge after 1876 – the “Ellis Island of Los Angeles.” The area through which Anza traveled towards Yang-Na that surrounded the banana slug shaped SP rail yard became industrial. In 2001, that area became the Los Angeles State Historic Park.

The road they followed had been a meandering Indian road.

In 1836, the Mexican-era City government evicted the native people from what remained of Yang-Na. That amorphous open space left after the eviction became “la plaza,” which was contracted and shaped as a rectangle by 1860 in the American era. By the 1870s, it became the circular “plaza vieja” downtown.

A portion of the road the expedition followed began at City Hall and then went north along El Camino Viejo – a tri-part road that no longer exists — northeast through the hills more or less along today’s Glendale Boulevard, along the rim of Arroyo de los Reyes – that area now partly occupied by Echo Park Lake.

The “Official map of Los Angeles County, California: compiled under instructions and by the order of the Board of Supervisors of Los Angeles County, created by Valentine James Rowan in 1888,” can be expanded.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4363l.la000023/?r=0.434,0.572,0.056,0.036,0.

In 1888, the former arroyo was a reservoir – and had been a reservoir since 1868. The black line through designates the train line that began as the Ostrich Farm train into Griffith Park. That route was the predecessor to today’s Sunset Boulevard. The lake went all the way to today’s Effie Street.

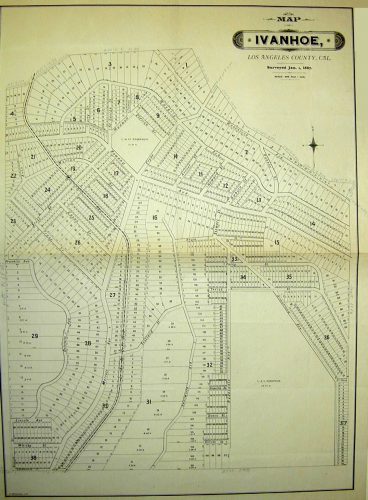

In 1888 – at least, according to this map, which, although “official,” is not accurate, especially in the area of “Ivanhoe,” then a “paper town” from the Boom of the Eighties” – the train tracks skirted the bottom of Reservoir Street.” Reservoir Street today ends abruptly above Silver Lake Boulevard. The street with the peculiar name Michael Toreno Street is today’s Micheltorena Street, named after the last Mexican governor of Alta California Manuel Micheltorena — the governor that confirmed the Feliz Rancho boundaries in 1843. This street is as steep as a roller coaster hill, maybe steeper.

The train line in the real landscape went along today’s Griffith Park Boulevard. Paralleling it is a double line indicating today’s Hyperion. In the real world, there is a steep hill between the rail line, “Michael Toreno Street” cresting it, and the next double line is at the bottom of the hill, now West Silver Lake Drive. The crooked double line to the right is today’s Silver Lake Boulevard. The meadow was the area between the last two double lines. Developers had planned a reservoir in the meadow as early as 1886, but it was not built as a reservoir until 1907, when William Mulholland engineered it.

Below is the 1886 subdivision map of Ivanhoe, a town that did not exist except on paper. The reservoir indicated towards the top, above Rowena Avenue, did exist before 1887. It is still there but no longer a reservoir. “Melrose Ave.” becomes “Clyde” on this subdivision map.

Sunset Boulevard occupied the upper portion of the former arroyo as of May 14, 1904.

Alvarado did not continue as far as Arroyo de los Reyes in 1776. The likely road Anza took through the hills was between Alvarado and Figueroa – the predecessor to today’s Glendale Boulevard.

Assuming Anza followed El Camino Viejo to the pass through the hills that once embraced Yang-Na and went roughly along Glendale Boulevard to the arroyo – and assuming the original contours of the arroyo were the same as the blob shape of Reservoir No. 4 – and assuming Anza skirted the bottoms of the steepest hills, the expedition went along the edge of the arroyo to the squiggly train route below the hills. As the map is incorrect, I can’t say whether they then went into the meadow and stopped for the night or followed the train route between the hills, crossed today’s Rowena and then descended to the flat area around today’s Los Feliz Boulevard and Riverside Drive.

The meadow fits within Font’s description of that day’s journey – that is, “on the right rises the snowy range, with another steep, steep range lying in front of it.” A person standing in the meadow – partly occupied today by Silver Lake – looked directly ahead at the snowy range (the San Gabriel Mountain Range) and directly ahead to the bottom peak of the “steep steep range” (the Verdugo Mountain Range).

The bottom of the Verdugo Mountain Range is still a steep peak. It may be seen near the Silver Lake Recreation Center at 1850 West Silver Lake Drive.

Font wrote that there was little water at the El Portezuelo campsite. If the Anza expedition had camped on the Los Angeles River, they would have had a lot of water. There was a spring and a creek in the meadow that became after 1907 Silver Lake.

Font’s directions, however, were to the north and northwest. To reach the meadow, the expedition would have traveled north, northeast and then north again.

To have seen the snowy mountains and the steep mountains on the right as they traveled, the Anza expedition would have had to have been traveling along a bank of the Los Angeles River or through Glendale and Burbank. The expedition, however, had crossed the river and then traveled three leagues – or three hours. They could not have camped in Glendale or Burbank. They could not have traveled north after crossing the river because the hills that are today’s Elysian Park descended to the river’s edge and still do.

Font could not have seen the “steep steep” range from the Cahuenga Pass. The distance from today’s City Hall over the pass to the location that the Anza Society has concluded was the February 21, 1776 campsite – Universal Studio – would have been considerably longer, and they could not have reached it by dusk.

In the 1868 George Hansen map – “Rancho de los Felis: division line, Coronel and Lick Properties” — the “Puerta Suela” was located in the Lick property.[34]

In a map from 1870, that area became “El Portrero.”[35] “El Portrero” means a landform that slopes upward to higher terrain. The area by 1870 meant the flat portion of the Feliz Rancho that could be irrigated. The Feliz heirs probably irrigated that land since 1855.[36]

By 1870 “El Portezuelo” could have been any of the Feliz Rancho that bordered the river and extended west, including today’s Silver Lake (and the area below it at least to today’s Sunset Boulevard), the area around Riverside Drive and Los Feliz Boulevard, and the corridor of land from about the former Walt Disney Studio along Hyperion Boulevard.

There were two areas with a spring and creek: an area in the Hyperion Boulevard corridor and Silver Lake.

The expedition continued to Monterey, reaching it on March 10th after a journey of 130 days and nearly 2,000 miles of travel.

The settlers remained in Monterey. They were to remain there for several months because of Military Governor of the Californias Fernando Rivera y Moncado’s opposition to a San Francisco settlement.

On March 23rd, Anza, Font, Lieutenant Moraga, eight soldiers from Tubac and several local guides continued to what is now San Francisco, where Anza sited the mission and the Presidio on March 28th. The Presidio was not built on the location Anza chose.

This smaller party went southward around the east end of the Bay, then northwest through today’s Berkeley to Rodeo Creek, through today’s Martinez to today’s Concord, where they camped on the arroyo near today’s Willow Pass Shopping Center and up Willow Pass Road to today’s Antioch.

From Antioch, they traveled southeast to the Livermore Valley, south along the edge of Crane Ridge into San Antonio Valley and Arroyo del Coyote, and finally south to today’s Salinas. By April 8th, Anza was back in Monterey.

What happened to the overland route Anza opened from Mexico for Spanish Colonization

Over three days – July 17, 18 and 1781 – Quechan Indians destroyed two Spanish mission-pueblos at the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers, at what would be known as the Yuma Crossing.

“’The Yuma Massacre closed the overland route to Alta California, and with it passed Alta California’s chance for early populous settlement. It meant that gold was reserved for discovery in 1848…. Alta California settled down to an Arcadian existence, able to live happily and well, and to keep out the casual foreigner but not populous enough to thrust back up the river valleys where the magic gold, which, had it been discovered, would at once have changed everything.’”[37][38]

The land route from Mexico through the desert that Anza opened for Spanish colonization was to remain closed for fifty years. Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821.

Epilogue

Gálvez’s vision of a colonized California sufficiently populated to withstand foreign invasion did not occur. Instead, the sparsely settled pueblos and presidios became an invitation to invasion.

If Spain had not sent its priests, soldiers and colonists to California, the United States would have taken the land but their soldiers and their settlers would have encountered even more difficulties because they would have faced a large number of Indians.

Without Mexican cattle, without Mexican agriculture, Americans would have had to ship in all supplies. The Gold Rush would have been postponed for a long time. That time might have been long enough for a compromise between the indigenous people and the American invaders – or not. There may have simply been a longer and bloodier genocide.

Father Serra did not achieve one of his dreams: to die a martyr. He did achieve his dream of personally converting the gentiles, introducing them to agriculture and crafts, at great human cost: the mission system introduced European diseases that killed the native people. He introduced concepts of shame and guilt and corporal punishment. Under the mission regime – although very much against the padres’ wishes — soldiers raped Indian women.

Pope Francis canonized Father Serra as a saint on September 23, 2015.

[1] Gary Kamiya, “When Columbian mammoths roamed San Francisco,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 27, 2015.

[2] See, e.g., George T. Jefferson, Judith L. Goldin, “Seasonal migration of Bison antiquus from Rancho La Brea,” Quaternary Research, Volume 31, Issue 1, January 1989, pages 107-112. Becky Oskin, “Swimming Mammoths Beat Humans to California,” Live Science, October 23, 2014. (Mammoths were in Northern America for 1 million years.)

[3] See, Paul S. Martin, Richard G. Klein, editors, Quaternary Extinctions ( University of Arizona Press 1989).

[4] Linda Watanabe McFerrin, “A Natural History of Oakland’s Lake Merritt,” Bay Nature magazine, January-March 2011. https://baynature.org/article/loving-lake-merritt/. (Retrieved 12/1/2018)

[5] From the Historic topographic maps of California: San Francisco Bay Region. Earth Sciences. UC Berkeley. http://servlet1.lib.berkeley.edu:8080/mapviewer/searchcoll.execute.logic?coll=histoposf. (Retrieved 11/29/2018)

[6] Frank M. Stanger and Alan K. Brown, Who Discovered the Golden Gate? The Explorers’ Own Accounts: How they discovered a hidden harbor and at last found its entrance (Published by the San Mateo County Historical Association 1969).

[7] “Devils Teeth, Mysterious Sharks,” Shark Stewards. http://sharkstewards.org/devils-teeth-mysterious-sharks/. (Retrieved 10/29/18) U.S. .Army Captain John C. Fremont looked at the narrow strait that separates for the Bay for the Pacific Ocean and said, “It is a golden gate to trade with the Orient. Until the 1840s, the strait was called Boca del Puerto de San Francisco.

[8] James J. Rawls and Walton Bean, California: an Interpretive History (McGraw Hill, 10th edition 2011)

[9] H. H. Bancroft, History of California, Vol. 1 1542-1800 (San Francisco, The History Company 1886), page 91.

[10] Herbert Eugene Bolton, Fray Juan Crespi, Missionary Explorer on the Pacific Coast 1769-1774 (University of California Press, Berkeley, California 1927) page xxxiii

[11] There were no buffalo in California in 1609. A relative — Bison Antiquus — became extinct between about 11,000 and 12,000 years ago in California at the end of the last glacial maximus. Paleo-Indians arrived in California at least 15,000 years ago. It is possible the Indians hunted these animals – and other large animals, like a relative to today’s camel, to extinction. Bison follow migratory trails – as do camels – and may have contributed to the creation of the Indian road system the land explorers followed.

[12] The nut larger than a chestnut could have been the California buckeye. The Indians, however, did not commonly eat them. The seeds, bark and flowers are toxic and can produce stomachache, spasms, diarrhea, disorientation and even death at high doses. The native people may have leached the nuts to remove toxicity. Acorns also had to be leached to remove tannic acid.

[13] Diary of Sebastian Vizcaino, 1602-1603, Document No. AJ-002, American Journeys Collection, Document No. AJ-002 (Wisconsin Historical Society Digital Library and Archives.) http://www.americanjourneys.org/pdf/AJ-002.pdf. (Retrieved 10/2018) , pages 90-92.

[14] Donald C. Cutter, “Plans for the Occupation of Upper California A New Look at the ‘Dark Age’ from 1602 to 1769.” The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society, Winter 1978, Volume 4, Number 1.

[15] John Rawls and Walton Bean, California: An Interpretive History (8th edition, McGraw Hill 2003). page 65.

[16] Herbert Ingram Priestly, José de Gálvez, Visitor-General of New Spain (University of California Press 1916), pp. 253- 254.

[17] Cutter, supra, contradicts the conclusion that theory that the 1769 scheme was a “madcap scheme of a mad genius” by providing a history of pre-Serra religious interest and royal concern from 1715 to colonize San Diego and Monterey.

[18] Beebe and Senkewicz, Junípero Serra : California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary (University of Oklahoma Press 2015), page 423-424.

[19] Id, page 424.

[20] In 1691, the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City, the Conde de Monterrey, appointed Vizcaino to lead an expedition to locate safe harbors in Alta California for Spanish Galleons to use on their return trip from Manila to Acapulco. The decision to develop Monterey was deferred for 163 years.

[21] The San Carlos ran aground in March 1775 when it was dispatched to Monterey. The crew of a rescue boat discovered that the San Carlos commander Diego de Manrique had gone insane and was armed with six pistols. The replacement captain was to shoot himself in the foot with one of the pistols Manrique had left behind.

[22] Scholars concur they went over the Sepulveda Pass but, looking at a late nineteenth century map, it seems the descent into the valley must have been very difficult.

[23] H. E. Bolton, “Expedition to the San Francisco Bay: Diary of Pedro Fages,” Publications of The Academy of Pacific Coast History, vol. 3. No. 2 (University of California, Berkeley, July 1911, pp. 143 -159.

[24] The early land explorers assumed “the Port of San Francisco” was Drake’s Bay.

[25] Bolton, Id, page 153.

[26] Stanger and Brown, page 19.

[27] Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, “Juan Bautista de Anza,” History.org. http://www.newmexicohistory.org/people/juan-bautista-de-anza. (Retrieved 10/16/18)

[28] Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, “Who Traveled with Anza?” http://www.solideas.com/DeAnza/TrailGuide/Anza_Roll_Call.html. (Retrieved 10/10/2018)

[29] Rose Marie Beebe, Robert M. Senkewicz, editors, Lands of Promise and Despair: Chronicles of Early California, 1535-1846 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015, originally published by Heyday Press) e-book.

[30] Aldous Huxley, “The Desert,” West of the West: Imagining California,” edited by Leonard Michaels, David Reid and Raquel Scherr (North Point Press, San Francisco 1989), page 320.

[31] Vladimir Guerrero, The Anza Trail and The Settling of California (Heyday Books 2006)

[32] Seminal Spanish Borderlands historian H. E. Bolton followed both journeys – sometimes on horseback, sometimes by automobile, and his wife drove the stretch between Berkley to Antioch. He went by train from Los Angeles on the Southern Pacific Railway.[32] Much of Bolton’s travel on the Anza trails was accomplished by 1909. Because of many projects as the head of the Bancroft Library and his teaching work at UC Berkeley, he did not complete his writing of the five volumes of Anza’s California Expeditions until 1929, published by A. A. Knopf between 1930 and 1939.

[33] “The Mission of San Carlos near Monterrey,” Captain George Vancouver, op cit.

[34] https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll4/id/11395/rec/7, “Rancho de los Felis: division-line; Coronel and Lick Properties, surveyed by George Hansen, 1868. (Retrieved 12/7/2018)

[35] “El Portrero or Irrigable Flat of the Rancho Los Feliz.” December 1870. https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll4/id/11397/rec/1. ( Retrieved 11/29/2018). The second map is also on the Huntington Digital archives. “Suela” means sole of a shoe. “Puerta” means door.

[36] Mayberry v. Alhambra Addition Water Co. July 22, 1899, The Pacific Reporter, Volume 58, pages 68, 70

[37] Charles Edward Chapman, cited in Mark Santiago, Yuma Crossing, Spanish Relations with the Quechans, 1779-1782, (The University of Arizona Press, Tucson 1998), page xi

[38] The “Arcadian existence” Guerrero described depended on scarcely paid Indian labor on land carved from Indian land.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.