Honey investigates the site of the first pueblo of Los Angeles

Many people who visit Los Angeles believe that the city began around the “Old Plaza,” the plaza near Olvera Street. The newer plaza was “La plaza abaja,” which is now called Pershing Square, and that plaza began in 1849.

A plaque across from the Old Plaza commemorates the founding of the city. It states: “On September 4, 1781, eleven families of pobladores (44 persons including children) arrived at this place from the Gulf of California to establish a pueblo which was to become the City of Los Angeles. This colonization ordered by King Carlos III was carried out under the direction of Governor Felipe de Neve.”

Wikipedia states that the area around the plaza was the city’s center under Spanish rule (1791 to 1821), and Mexican rule (1821-1847). The Spanish founded Los Angeles in 1781.

Wikipedia almost immediately in the same essay contradicts its early statement. “The original pueblo was built to the southeast of the current plaza along the Los Angeles River. In 1815, a flood washed away the original pueblo, and it was rebuilt farther from the river at the location of the current plaza.” This portion of the Wikipedia essay cites the Department of Public Works for Los Angeles County. http://dpw.lacounty.gov/wmd/watershed/LA/History.cfm.

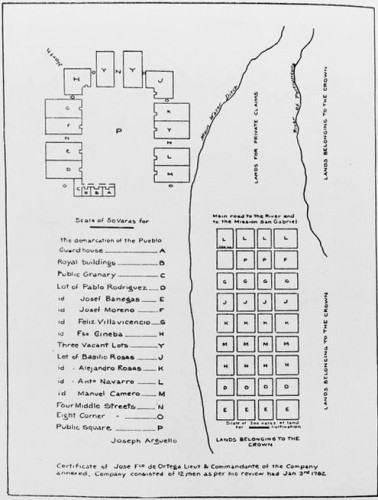

Map of LA in 1783. Courtesy

of Bancroft Library.

Zanja Madre Map shows LA in the 1860s.

Ina Coolbrith lived on Arcadia Street

Courtesy of Bancroft Library.

The Department of Public Works website actually reports: “In 1815 the Los Angeles River floods washed away the original Pueblo de Los Angeles.” That article does not indicate where the first pueblo was.

A major flood did shift the river’s course in 1815 from the eastern to the western side of the valley. Historians believe the original settlers may have had to move the plaza several times, however, before 1815.

In about 17 69, Father Juan Crespi, a Franciscan priest who, more than a decade earlier, accompanied the Gaspar de Portola expedition – first European land expedition through California – recommended a site for the pueblo. The location he recommended was at the confluence of the Arroyo Seco and the Los Angeles River. He described the confluence as “very well lined with large trees, sycamores, willows, cottonwoods, and very large live oaks.”

De Neve based his siting of the pueblo on Crespi’s recommendation.

The plan De Neve drew for the future pueblo accompanies this essay. Someone translated the words into English; nonetheless, it is the same design as the original. The plan envisioned a ditch to carry water from the river to the pueblo, including the original plaza (“P” on the plan), later to be called “the zanja madre,” under the Spanish regime, simply “la zanja,” from a point on the river.

The Zanja Madre was placed at a location close to present-day Broadway at the foot of the Elysian Hills by the river. An earth and brush dam, called a toma, was created to pool up the water into the ditch which then ran along an elevated slope down to the pueblo and from there to agricultural land.

The zanja carried the water along the south-eastern side of the pueblo and south from there to land allotments, called “suertes.” “Suerte” in Spanish means “luck,” but in Spanish land ownership, the term meant a lot to grow food, and the primary food grown by the Spanish settlers was corn.

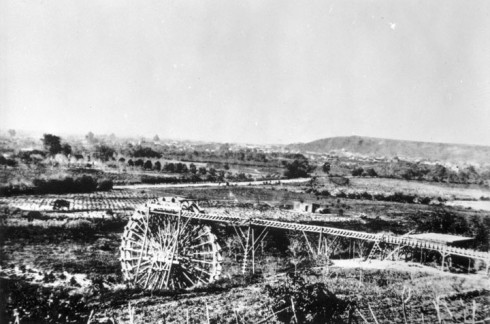

The Americans after 1850 lined the zanja with brick to reduce evaporation. In 1863, a private water company built a water wheel at the place where the Broadway bridge crosses the river to increase the water flow. The zanja was the primary water source for the city until the early twentieth century. William Mulholland’s first job in Los Angeles was as a maintenance worker on the water ditch, working for the “zanjero,” the most highly paid official in the city.

In 2005, amateur archeologists found a piece of the zanja madre near New Chinatown in the area known once as “the corn fields.”

Looking back at de Neve’s design, the original pueblo was sited a little to the north-west of the suertes. The present-day Los Angeles State Historic Park, the address for which is 1245 North Spring Street, was once called “the Cornfields.” The edge of the Cornfields closest to the river is near the Broadway Bridge. The other end of the park is near New Chinatown. It is today, and possibly in the nineteenth century, about a fifteen-minute walk from today’s plaza near Olvera Street to the beginning of the area once referred to as the Cornfields.

Water Wheel installed on LA

River near future Broadway Bridge.

1870s. Courtesy of LAPL

The current belief as that the area called “the Cornfields” had that name because that was the location for the Southern Pacific Railroad’s river station – it was still a railroad area in my childhood – and the theory is that the Cornfields had that name because corn kernels fell from the trains. The more likely explanation is that, before the Southern Pacific Railroad built the river station in 1875, that the area had been the actual cornfields for the original pueblo.

If the de Neve design is accurate, and if “the Cornfields” were the suertes established by the first settlers, that places the site of the first pueblo – and the beginning of Los Angeles – at around an area between the park and North Broadway.

The poet Ina Coolrbrith when she was a young wife named Josephine D. Carsley, lived in an adobe house connected to her husband Robert Carsley’s Salamander Ironworks from 1858 to sometime in 1861. Abel Stearns, “Old Horseface,” a Jewish convert to Catholicism married to Arcadia Bandini, owned their property. The location of the Salamander Ironworks is where the 101 Freeway goes through downtown near Arcadia Street.

The Carsley couple had a child, probably a boy, in 1861. The Carsley divorce file at the Huntington Library does not show the existence of a child. Robert and Josephine’s divorce concluded on December 30, 1861. If the child had been alive, he would have been mentioned in the divorce, because the law at the time assumed that a child born during a marriage was the husband’s child. The divorce decree not only dissolved the marriage, it also annulled it and made it void from its inception. Under today’s marriage laws, the marriage could not be both annulled and dissolved.

Ina Coolbrith wrote that her autobiography was to be found in her poetry.

Ina’s poem, “The Mother’s Grief,” suggests there had been a child.

“So fair the sun rose yester-morn, the mountain cliffs adorning; the golden tassels of the corn danced in the breath of the morning; the cool clear stream that runs before, such happy words were saying.

“And in the open cottage door my pretty babe was playing. Aslant the sill a sunbeam lay; I laughed in careless pleasure to see his little hand essay to grasp the shining treasure.

“Today no shafts of golden flame across the sill are lying; today I call my baby’s name, and hear no lisped replying; today – ah, baby mine, today – God holds thee in His keeping!”

“And yet I weep, as one pale ray breaks in upon they sleeping – I weep to see its shining bands reach, with a fond endeavor, to where the little restless hands are crossed in rest forever.”

The poem’s images – mountain cliffs, corn tassels, a cool stream – suggest the San Gabriel Mountains that rise as gigantic background to the pueblo, and indicate there was a cornfield at the edge of the pueblo that extended to the Los Angeles River. Corn in California is harvested from June to August, dry season in Los Angeles, so the river may have been a stream.

The following year – 1862 – was “the Great Flood.” The rains did not seem to end, and the pueblo residents lost all value they had in their land. Even Abel Stearns could not sell his lands at any price.

This small poem about a mother’s grief reveals that there were cornfields in 1861, not far from where she, her husband Robert, and the child lived. There was no other area for cornfields in 1861, that could have grown the corn she describes in her poem but the area within the Los Angeles State Historic Park.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.