Honey goes around and around Griffith Park with Anza

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

This is an undated photograph of members of the Cahuenga village camping on the

Cahuenga Pass. Anza Society website.

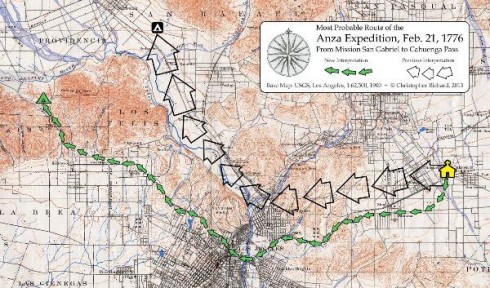

Old Way Stack Cropped is the map that accompanies Professor Quinn’s essay on the

Anza route. I got it from the Anza Society website.

It’s well known that Walt Disney first thought up Disneyland when he was sitting on a bench in front of the merry-go-round in Griffith Park (4730 Crystal Springs Drive). The Department of Parks and Recreation donated the bench to Main Street, U.S.A., so you have to go to Anaheim to see it. It’s currently on display in the Opera House lobby. James Dean’s bronze bust at the Griffith Park Observatory atop Mt. Hollywood (on the sidewalk to the west of the main lawn) commemorates the making of key scenes in Rebel Without A Cause. The 1960s Mission Impossible television series used the merry-go-round, the observatory, the tunnel – I think that’s the same tunnel as in Who Framed Roger Rabbit that is the entrance to Toontown – and the Bronson Caves. Griffith Park also sometimes played other planets in the television Star Trek series. Griffith Park ends on the western side a little to the east of Universal Studios. Before that, Griffith Park played a role as a civil war battlefield and many roles as a Far West landscape for cowboy films, both silent and talkie.

Long before movies and cartoons, the Griffith Park part of the Santa Monica Mountains was inhabited. The mouth of Fern Dell Canyon (Los Feliz Boulevard, Red Oak Drive, Fern Dell Place) was a Tongva village site. The Tongva village of Kah-Ween-ga (Cahuenga) was on the banks of the Los Angeles River, probably on the San Fernando Valley side of the pass. Indians lived in the Los Angeles area, including the San Gabriel Valley and the San Fernando Valley, for at least 8,000 years pre-contact with Europeans.

The first Europeans came by ship. It took quite some time before Europeans went into the interior of Alta California. Both the Portola and the Anza expeditions traveled through the Los Angeles area before the Spanish established the pueblo of Los Angeles. There is some dispute about what route the Anza expedition — 240 colonists, horses and pack mules accompanied Captain Anza on his second journey — took through Los Angeles from the San Gabriel Mission. Most sources feel that Anza went west, south and then north. I don’t think that. I think Anza went west-north-west, just as his diarist Fr. Font said. That makes a difference: most people feel he followed the Portola route to about the confluence of the arroyo seco and the LA River near what is now Elysian Park, and then through what would one day be downtown Los Angeles.

I think Anza went through Highland Park to about where Atwater Village is and crossed the river at about where the Hyperion Bridge is.

Most sources agree that Anza went up the gap between what is now called the Santa Monica Mountains and the Verdugo Mountains and camped over night at the northeast corner of Griffith Park and then went through the San Ferndando Valley. Scholars in the Anza Society, however, feel Anza went through Hollywood and over the Cahuenga Pass, camping at about the access road to Universal Studio. I agree with most sources and disagree with the Anza Society.

Spanish explorers reached the coast of California by the sixteenth century. In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno surveyed several locations in his coastal exploration, including San Diego, Santa Barbara and Monterey. For the next 160 years, the only settlements made by the Spanish were in Baja California.

The Gaspar de Portolà expedition in 1769–1770 jjjjpaved the way for Spanish colonization of Las Californias Province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (colonial Mexico). Father Juan Crespi was one of the diarists on the second expedition a year later.

Gaspar de Portola’s expedition crossed the river in 1769 at about the place where the Arroyo Seco meets it; that is, a short distance from the steepest hill in Elysian Park, a hill that stands out as you drive north on the Golden State Freeway and also if you drive towards it from Highland Park. The tall hill is a significant landmark for those attending games at Dodger Stadium. Fr. Crespi, who accompanied the expedition, named the river El Río de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles de Porciúncula. The name derived from a small town in Italy that housed the Porciuncula — the church where St. Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan order carried out his religious life. “Porciuncula” means a small portion of land, and upon it the church had been built. The river was to change course in 1825.

Fr. Crespi wrote on the second Portola expedition:

“After traveling about a league and a half through a pass between low hills we entered a very spacious valley, well grown with cottonwoods and alders, among which ran a beautiful river from north north-west and then doubling the point of a steep hill, it went on afterward to the south.” The expedition also found oil bubbling out of the ground at what would become the La Brea Tar Pits.

After crossing into the San Fernando Valley over the Sepulveda Pass, Fr. Crespi wrote:

“We saw a very pleasant and spacious valley. We descended to it and stopped close to a watering place, which is a large pool. Near it we found a village of heathen, very friendly and docile. We gave to this plain the name of Santa Catalina de Bononia de Los Encinos. It has on its hills and its valleys many live oak and walnuts. “ Motorists now drive over the Sepulveda Pass on the 405 to reach Encino.

Pere Fages – later second lieutenant Governor of Las Californias province of New Spain (1770-1774) and then the second Governor of Las Californias (1782-1791) – found an easier route to San Francisco than the coastal route followed by Portola, this one through Salinas and the Santa Clara Valley, today’s Route 101. Fages’ route became the preferred route.

Juan Bautista de Anza began his first expedition on January 8, 1774, accompanied by three padres, 20 soldiers, 11 servants, 35 mules, 65 cattle, and 140 horses from Tubac presidio, south of present-day Tucson Arizona. They reached the San Gabriel Mission on March 22, 1774, and to go north into the San Fernando Valley he crossed the Los Angeles River and went through the gap between the last steep hill of the Santa Monica Mountains and the Verdugo Mountains. They reached Monterey, capital of Alta California, on April 19, 1774. He returned to Tubac.

The viceroy and the king promoted Anza to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. He formed a second expedition to lead a group of colonists from Tubac to Alta California. With the cry, “Vayan subiendo!” (“Everyone mount.”) the second Anza journey began on October 2, 1775.

The 240 men, women and children in the expedition suffered greatly from the winter weather on the route to the Mission San Gabriel, which they reached in January 1776. The wife of the soldier Feliz died in childbirth, but during the trek the group added 3 infants. There were no roads, so pack mules carried their belongings.

This is what Friar Font, who accompanied the group as padre, diarist, cartographer and geographer, wrote about the Anza colonists travel from the San Gabriel Mission to the San Fernando Valley:

“February 21, Wednesday. I did the blessing of ashes; I said Mass, and during it, four words to the people who were remaining and to the rest of them who were going (who wept a bit since they regretted this separation) by using the gospel of the day to reaffirm what I had been saying to them in the talks I gave them. That is, that they had come in order to suffer and give an example of Christianity to the gentiles, etc., the whole of it amounting to exhorting both groups to repent for their faults and patience in hardship, etc., etc. We set out from Mission San Gabriel at a half past eleven in the morning and halted at a half past four in the afternoon at the spot called El Portezuelo having traveled for five leagues following a west-northwestward course with some veering to one side and the other. At two leagues we crossed the Porciuncula River, which carries a good amount of water and runs toward the San Pedro bight, and spreads out and loses itself upon the plains shortly before reaching the sea. The land was very green and flowery and the route had a few hills and a great deal of miry grounds created by the rains. This is why the pack train fell far in the rear. At the stopping place there is year-round water, although little of it, and sufficient firewood. As one goes along, far off on the left hand, upon the sea, lies the hill range forming the San Pedro bight, and on the right rises the snowy range, with another steep range lying in front of it.”

A “bight” is a curve or recess in a coastline or river. Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo discovered the bay that would be known as San Pedro in 1542. He named it for St. Peter of Alexandria because he found the bay on St. Peter’s feast day. Fr. Font knew enough about the geography of the Los Angeles basin to be able to explain that the river ran toward San Pedro. It might have been possible then to see the hill range forming the San Pedro bight from flat areas but today you couldn’t see it unless you climbed up something quite high in the Santa Monica Mountains.

The “snowy range” was probably the San Gabriel Mountains, which is sometimes snow-covered in wet winters. The smaller range then was the Verdugo Mountains. For Fr. Font to have seen these mountain ranges from the same trail as he saw the San Pedro bight means he had to have been at a summit in the Santa Monica Mountains. You can see both the San Pedro bight and the two ranges from the Griffith Park Observatory. Inasmuch as Font was in a group of 240 men, women and children on horseback, accompanied by pack mules, I’d hazard a guess that they did not climb up to a height where they could see both the mountain ranges and the bight at the same time.

Puertozuelo in modern dictionaries comes up as “pass.”

According to Josiah D. Whitney’s Studies in Geographical and Topographical Nomenclature (Cambridge University Press 1888), however, puertozuelo was more correctly a “divide” in older uses in California. Whitney maintained that English-speaking people in parts of the California Coast Ranges used the word puertozuelo to mean “the divide” up to the time that he wrote his book. The “divide” is the elevated boundary between areas that are drained by different water systems. A divide is also defined as a high point that determines the direction that rivers will flow.

As explained a little later, “El Puertozuelo” as used by Fr. Font is – so far – recognized by the National Park Service as that point in the Los Angeles River where the river goes around that last tall hill and abruptly heads south.

The Spanish league is about three miles as used in California and Texas. This means the Anza group traveled six miles to the Los Angeles River from the Mission following a west-northwestward course. Fr. Font was a “cosmographer,” and he was able to wrest the primitive geographic instrument from Anza and had a mathematical table he used to interpret readings. The area between the mission and the river contains several hills – some abrupt, small and steep, some quite tall. Today’s main roads from the mission to the river going in a north-north-westerly direction almost entirely are in the flat areas between the hills. It is about ten miles, however, along mostly York Boulevard from the mission to Atwater Village, which is on the banks of the concretized LA River. The river, of course, was not then contained in a concrete sepulcher, but if Anza went north-north-westerly, then they had to have crossed the river at where the Hyperion Bridge now crosses it or where the Los Feliz Bridge crosses it or at Rattlesnake Park. If Anza had taken that route, the group would have crossed the river after about 10 miles, or over 3 leagues. This area would have been boggy in rainy weather.

Anza would have crossed wherever it was the easiest. There was gravel in the riverbed then, so the pack animals and the horses would have been able to have a sure footing at either location. Generally, then, they may have traveled through Highland Park to Eagle Rock to Glassell Park, possibly over the river where the Fletcher Drive Bridge crosses it and then north along what is now Riverside Drive. Professor Ronald D. Quinn, however, in an essay published by the Anza Society, indicates Anza crossed the river at about the place where the Arroyo Seco joins it, near Elysian Park. In a rainy season, the confluence of the water in the river and the water in the arroyo would have made that point of crossing very difficult.

They reached “El Puertozuelo” after “five leagues.” It isn’t clear to me if Fr. Font meant five leagues from the mission or five leagues after crossing the river. The National Park Services recognizes this location as the John Ferraro Soccer field at the North-east end of Griffith Park. A bronze plaque near to the soccer field commemorates the Anza colonist’s first stopping place after they left the San Gabriel Mission. This is the location identified by Professor Herbert Eugene Bolton in his seminal work Anza’s California Expeditions (1931)

The woman who lost her life giving birth on the Anza trail was the wife of soldier Juan Feliz. Later on, Governor Fages granted Juan Feliz grazing rights to one league-square of land that included all of Griffith Park, and that included “El Puertozuelo,” the Anza stopping place. The Feliz adobe is the ranger station on Crystal Springs road, although much changed. Antonio de Coronel, once mayor of Los Angeles, eventually acquired the Feliz Rancho, after him Griffith J. Griffith acquired the land, which included much of what is now the Silver Lake district, and he donated that big chunk of real estate, including El Puertozuelo,” to the City of Los Angeles.

Several Anza scholars in the Anza Society, including Phil Valdez, Jr., a descendant of a soldier in the Anza expedition and immediate past president of the Anza Society, however, argue that the colonists took a different route.

Professor Ronald D. Quinn writes: “In 1931 Herbert Bolton…., wrote that Anza had passed north of the Los Angeles Basin, following the Los Angeles River around the east end of the Hollywood Hills, skirting contemporary Griffith Park, through the Glendale Narrows and into the San Fernando Valley.” (http://anzasociety.org/Cahuenga.html.)

Professor Quinn argues that the Anza colonists went across the river down by Elysian Park and then went north along what would one day be Sunset Boulevard and then went up over the Cahuenga Pass into the San Fernando Valley. He attaches a map – a map that started as a 1908 topographic map but which has been cropped – showing that Anza went west south-west instead of as Fr. Font wrote west north-west, crossing the river at about the steep Elysian Park hill. Notes on the map indicate Christopher Richard designed the cropped map.

Christopher Richard, former curator of aquatic biology at the Oakland Museum weighed in for the Downtown to Hollywood route and gave another reason why Anza would have decided to go a new way.

Richard wrote, “‘The area labeled Providencia (Burbank, Studio City) would have had numerous seeps, mires, sausals, and other riparian thickets; in short, not a good area for travel with hoofed animals. The relatively small elevation gain and loss over Cahuenga Pass would have been readily offset by the better footing for the livestock.’”

“The argument in favor of the Hollywood route is further strengthened by the weather that particular winter. It is clear from Font’s diaries that it had been rainy at the very time they crossed the Los Angeles area (Dec 1775 – Feb 1776). As the Anza Expedition crossed Los Angeles on February 21 Font describes very miry ground created by the rains, which caused the pack train to fall behind the rest of the expedition. Earlier in the winter, on New Year’s Day, they had taken an entire day to cross the swollen Santa Ana River at the City of Riverside. On the other hand, they reported no difficulty three days later in crossing the flood plain of the mighty San Gabriel River as they approached the San Gabriel Mission, although Font noted the wide alluvial fan that still exists at the mouth of its mountain canyon. Not long before Anza arrived in the winter of 1776, the San Gabriel Mission was moved north from its original location due to flooding of the San Gabriel River….”

Anza scholar Alan Brown wrote that the February 21 campsite was in Hollywood at the south end of the Cahuenga Pass, placing the campsite on what would be the site of the Hollywood Bowl. Quinn’s opinion, based on the distance Anza covered the next day, that the site was on the north end of the pass, about the exit from the freeway to Universal Studios.

Fr. Font wrote in his diary:

“February 22, Thursday. We set out from El Portezuelo at eight o’clock in the morning and halted at a quarter past three in the afternoon at the spot called El Agua Escondido, which lies before the spot called El Tirunfo where we hoped to arrive today. We traveled nine leagues on a westward course with some veering. Shortly after setting out from the stopping place, we came into a very spacious valley called Santa Isabel, at the middle of which and at a little over three leagues is the place called Nogales, which is a small spring of water like a little lake, issuing in the midst of the plain, near which there are small walnut trees. And at about seven leagues, we came to the foot of the mountains, which together with the range which we crossed the gap yesterday, and today have been leaving upon our left, and with the other range running in front of the snowy range of mountains, which we had been having on our right, make this valley and it ends here. We went into a hollow, which has a very small amount of water and then spent about two leagues going over grades as far as the stopping place, with also a hollow with little water and a good many live oaks. It is formed by a number of hills belonging to a mountain spur that departs from the main range and extends toward the sea. Because of the windings about, our course turned as far as southwestward. Along the way we saw gentiles, although just a few of them and they were naked and entirely weaponless. Even so, they refused to approach us.”

I don’t know but the very spacious valley may have been the entire San Fernando Valley. There was a thermal hot springs and a lake in Encino. The distance from the northeast end of Griffith Park to Encino is 13.5 miles. It seems from reading this – to me it does – that Anza rode from the end of Griffith Park on the valley side near what would one day be the Providencia Rancho (Burbank mostly) – to Woodland Hills in one day.

According to Google maps, that journey on foot is 18.4 miles.

My money is on the site that Bolton identified as the Anza stopping place in 1776: the northeast corner of Griffith Park.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.