Honey begins a three-part series on Helen Hunt Jackson

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

During the Victorian era on the east coast of the United States, the terrible voluminous roar of skirts worn over stockings, drawers, chemises, corsets strengthened with steel or whalebone, over as well the flexible cages of steel that supported the skirts and the layers of petticoats filled the rooms of houses.

The “angel in the house” ideal for Victorian women represented the ideology of gender: men dominated work outside the home and owned the political and legal system. Women were to raise virtuous children. Women were to be pure.

East coast privileged girls learned reading, writing and arithmetic but most people believed “important subjects” such as Latin, Greek or higher mathematics overtaxed women whose reasoning powers were too defective for such “masculine mysteries.”

Out of this white upper class female domestic milieu stepped a fleshy, very short upper middle class white woman writer with an unusually assured and balanced expression born Helen Maria Fiske in 1830 in Massachusetts.

Almost everyone seemed to admire her. A few loved her. Her reading audience was immense. A few members of Congress – of course, Congress was male — became irate but Congress did not entirely ignore her.

That Helen became a well-known poet and popular short story writer, was later commissioned by the federal government to research Mission Indians in Southern California, and wrote a book that led to cultural myths that were to transform California means the actual experience of women in the Victorian Era in the United States was more dimensional than the limited role cast for them.

In her youth, Helen married the man she loved – Edward Bissell Hunt — and they had two children. One of Helen’s sons died in infancy. Her husband died in a military accident. Her older boy died not long after.

“After her second son’s death Helen rarely spent time at home even after she remarried in her forties. Tragedy thrust her out of the idealized role for Victorian women. She wrote poetry that was quite popular but, as her friend Emily Dickinson commented, it didn’t “phosphoresce.” Dickinson was a poetic genius. Helen was a regular person who wrote for people like her until she surpassed herself in her fierce advocacy for this nation’s indigenous people.

“Helen published short stories most frequently and very successfully under the androgynous names “H.H.” (Helen Hunt) — and “Saxe Holme,” a made-up name.

Both H. H. and Saxe Holme stories describe people Helen encountered in Europe and in the United States who were not of her class. Although she wrote sympathetically, the subtext assumes caste distinctions. Helen precisely captured her lower class and foreign characters’ colorful broken or misspoken English. The effect of this writing was to create portrayals of quaintness and humor. Helen did not develop character. None of her subjects in these stories grow in understanding. Her plots were contrived and rather weird. The ideology of her time, unsurprisingly, permeated her work but she twisted it to reveal female courage. Her novel Ramona continued Helen’s approach to fiction, which meant that a work she intended to enlighten the public’s understanding of the American treatment of Southern California Indians was a melodrama, eventually turned into three melodramatic films: the first starring Mary Pickford in 1910, the second starring Dolores del Rio (1928), and the third starring Loretta Young (1936).

At one point in Helen’s earlier writing, she abruptly took a stand against corporal punishment of children. . She wrote, “I myself was whipped, not immoderately – not half so often as I deserved punishing in some way – but I never lacked anything but the power to kill every human being that struck me. I had as keen a sense of the outrage of a blow, at ten, as I have at forty.” Her outrage over cruelty grew out of her upbringing as the child of a Unitarian professor, probably the same person who beat her for not being at all the virtuous girl child that her sister was. This outrage against brutality was to underlie her later passionate activism on behalf of Native Americans.

“Helen visited California several times. She wrote about her travels in this state in 1872 — about twenty years after the state entered the union, six years after the end of the American civil war, and 12 years before she published Ramona. She was forty-two years old when she set off on her first trip to this state. She wrote that, when she decided to travel to California, it was a place as remote to her as Patagonia.

Helen’s California travel writing reads like long letters from a clever middle-aged friend who rapidly jotted down everything she saw and heard: her arrival through Truckee by train, across the Central Valley to San Francisco, to the Geysers near Healdsburg, to San Jose, by stage coach over the mountains to Santa Cruz, and to Los Angeles County and to Riverside and San Diego Counties. Through her published writing about the places she visited, we see through her eyes California twenty years after the Gold Rush.

“The California Helen saw is American, and it is largely Protestant. In 1871, the American population exceeded the Mexican and Indian populations for the first time. The “echoes” she hears in her 1872 piece about Los Angeles were the echoes of Mexican and Indian voices in by then the mostly Anglo city.

“Helen wrote in “Echoes in the City of Los Angeles”:

“The City of the Angels is a prosperous city now. It has business thoroughfares, blocks of fine stone buildings, hotels, shops, banks, and is growing daily. Its outlying regions are a great circuit of gardens, orchards, vineyards, and cornfields, and its suburbs are fast filling up with houses of a showy though cheap architecture. But it has not yet shaken off its past. A certain indefinable, delicious aroma from the old, ignorant, picturesque times lingers still — not only in byways and corners — but in the very center of its newest activities.

“Mexican women, their heads wrapped in black shawls, and their bright eyes peering out between the close-gathered folds, glide about everywhere; the soft Spanish speech is continually heard; long-robed priests hurry to and fro; and at each dawn ancient jangling bells from the Church of the Lady of the Angels ring out the night and in the day. Venders of strange commodities drive in stranger vehicles up and down the streets; antiquated carts piled high with oranges, their golden opulence contrasting weirdly with the shabbiness of their surroundings and the evident poverty of their owner; close following on the gold of one of these, one has sometimes the luck to see another cart, still more antiquated and rickety, piled high with something — he cannot imagine what — terracotta red in grotesque shape; it is fuel ,,, It is the roots and root-shoots of Manzanita and other shrubs. The colors are superb — terra-cotta reds, shading up to flesh pink, and down to dark mahogany; but the branches are grotesque beyond comparison: twists, queries (?) contortions, a boxful of them is an uncomfortable presence in one’s room, and putting them on the fire is like cremating the vertebra and double teeth of colossal monsters of the Pterodactyl period.

“The present plaza of the city is near the original plaza marked out at the time of the first settlement; the low adobe house of one of the early governors stands yet on its east side, and is still a habitable building.

“The plaza is a dusty and dismal little place, with a parsimonious fountain in the center, surrounded by spokes of thin turf, and walled at its outer circumference by a row of tall Monterey cypresses, shorn and clipped into the shape of huge croquettes or brad-awls standing broad end down. At all hours of the day idle boys and still idler men are to be seen basking on the fountain’s stone rim, or lying, face down, heels in air, in the triangles of shade made by the cypress croquettes. There is in Los Angeles much of this ancient and ingenious style of shearing and compressing foliage into unnatural and distorted shapes. It comes, no doubt, of lingering reverence for the traditions of what was thought beautiful in Spain centuries ago; and it gives to the town a certain quaint and foreign look, in admirable keeping with its irregular levels, zigzag, toppling precipices, and houses in tiers one above another.”

“One comes sometimes abruptly on a picture that seems bewilderingly un-American, of a precipice wall covered with bird-cage cottages, the little walled yard of one jutting out in a line with the chimney-tops of the next one below, and so on down to the street at the base of the hill. Wooden staircases and bits of terrace link and loop the odd little perches together; bright green pepper-trees, sometimes tall enough to shade two or three tiers of roofs, give a graceful plumed draping at the sides, and some of the steep fronts are covered with bloom, in solid curtains of geranium, sweet alyssum, heliotrope, and ivy. These terraced eyries (nests of birds of prey) are not the homes of the rich: the houses are Lilliputian in size, and of cheap quality; but they do more for the picturesqueness of the city than all the large, fine, and costly houses put together.

“Moreover, they are the only houses that command the situation, possess distance and a horizon. From some of these little ten-by-twelve flower-beds of homes is a stretch of view which makes each hour of the day a succession of changing splendors — the snowy peaks of San Bernardino and San Jacinto in the east and south; to the west, vast open country, billowy green with vineyard and orchard; beyond this, in clear weather, shining glints and threads of ocean, and again beyond, in the farthest outing, hill-crowned islands, misty blue against the sky. No one knows Los Angeles who does not climb to these sunny outlying heights, and roam and linger on them many a day. Nor, even thus lingering, will any one ever know more of Los Angeles than its lovely outward semblances and mysterious suggestions, unless he have the good fortune to win past the barrier of proud, sensitive, tender reserve, behind which is hid the life of the few remaining survivors of the old Spanish and Mexican Regime….”

In 1850 — when Los Angeles first became American — a series of bald, treeless hills separated by gullies dominated the City’s western horizon. By 1872, however, American real estate development had begun to climb those hills.

There were no tiny Mexican houses on a precipice reached by a wooden stairway on any of the hills that today spread west from downtown Los Angeles today: Bunker Hill, Fort (Moore) Hill, Angelino Heights, Elysian Park. There are only two photographs from the time of Helen’s first visit that show a city “built in irregular levels,” although the city’s growth was pretty haphazard, but these are photographs of a hill that no longer exists: an earthen lump that was part of “Pound Cake Hill,” which adjoined Bunker Hill and that was close to Mexican Los Angeles around the plaza.

Prudent Beaudry began the development of Bunker Hill in 1867, the tallest of the once grassy hills that embraced Los Angeles. By the time of Helen’s visit, the Crocker mansion stood on Bunker Hill. A 1872 photograph of the Crocker mansion shows a horse-drawn carriage in the foreground. Not until 1901, however, when the funicular Angel’s Flight was built, however, did access become convenient. Lowered considerably, skyscrapers stand on Bunker Hill today.

The Protestant cemetery was on top of Fort Hill. The street that went along the bottom of that hill was Eternidad – Eternity Street. The City about ten years later divided Fort Hill and Bunker Hill by digging a way through the hills with a trolley line, which was the genesis of Sunset Boulevard.

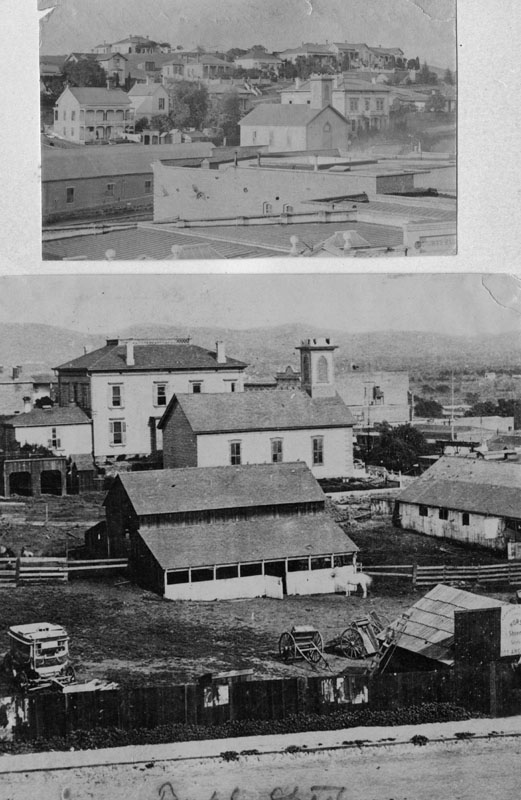

Photograph 1. What Los Angeles looked like in Helen Hunt Jackson’s time there. This photo is from the DWP. All the other photos of Los Angeles from that time are courtesy the Los Angeles Public Library downtown.

Photograph number two shows the other side of Pound Cake hill in 1871 – the side facing what will be Angelino Heights, then another grassy hill. Vigilantes lynched Michael Lachenais, a French property owner on Pound Cake hill the year before Helen’s arrival. Jacob Bell owned property next to his. Bell and Lachenais argued over the right to use water in the zanja – the water delivery system in ditches from the river) so Lachenais shot Bell and bragged about it.

Julian Chavez developed what was first called Chavez Canyon in the 1850s, but the houses on that hill – later Elysian Park (1886), Chavez Ravine, and which now includes Dodger Stadium – did not have the commanding views Helen described. In the film The Exiles, Native Americans living on Bunker Hill in the 1950s drive out to Elysian Park at night and sit on a hill top. The film was shot before Walter O’Malley ordered the deconstruction of an enormous hill in order to build his stadium – during that time, dust from the hill fell on the Echo Park neighborhoods for many months. From the hill, the main characters look down at the lights glittering like fireflies in Downtown out as far as the Pacific Ocean – but they do not have the perspective of the San Jacinto and San Bernardino Mountains from that vantage.

Imagine the comedic actor Melissa McCarthy – imagine her as tubercular and wearing a stiff corset and a huge skirt covering a steel cage climbing those very steep hills – and you may conclude it is unlikely that Helen climbed to those “sunny outlying hills.” A fit person can today climb all of those hills but now there are roads, and the hills are lower. One of the hills, the one I think Helen did climb, has been erased.

Photograph Three shows Los Angeles High School on Pound Cake Hill. The LAPL blurb indicates the Episcopal Church is in the foreground. I think it is the very steep roofed structure at the bottom of the incline leading to the school. The Church was on New High (later part of Broadway) and Temple.

Students reached the high school by going up a steep wooden stairway.

Photograph Four shows two views on the Congressional Church. This church was built in 1868 on Temple and New High. These do not show Los Angeles High School. Helen’s boarding house is the two- story building next to the church.

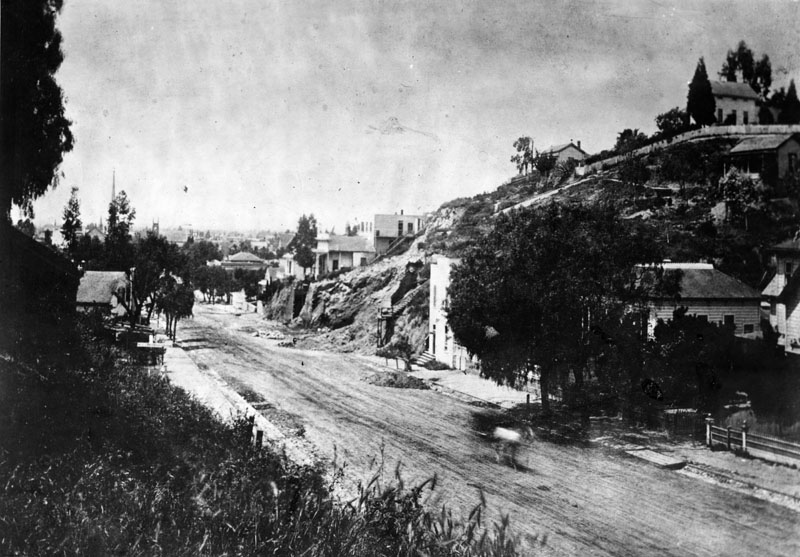

Photograph Five shows North Broadway in the area between First Street and “Temple Road” in after 1873 – the high school was built in 1873. You can see the First Congressional Church in the foreground next to a house.

In the pdf version of her piece “Echoes in the City of Los Angeles,” (The link is at the end of this essay.) an illustration shows a woman standing on the stairs. From the illustration, the wooden stairs are built against the south-western side of a building, so the stairs would be concealed in the Los Angeles Public Library photographs, which I labeled photographs numbers four and five.

Photograph Six shows the same area, shot from a slightly different perspective. This is North Broadway between First and Temple. In this photo, you can see what looks like a stairway in about the middle of the photograph. The hill has been excavated to create a dirt road. It is fairly steep. A wooden stairway can be seen in about the middle of the photograph. There are small houses, and one fairly large house at the top of the hill. There are paths connecting leading from either a very steep path or another stairway. I only see one tiny old house on the hill — perhaps two if that box-like structure on the wooden stairway counts. Outside frame of this photograph, however, there could have been at least several other tiny old houses. That hill on the right side of the photograph is gone. It is my candidate for “a precipice wall covered with bird-cage cottages, the little walled yard of one jutting out in a line with the chimney-tops of the next one below, and so on down to the street at the base of the hill.”

It is not difficult to imagine Helen walked about a block from her boarding house on the other side of the church to reach the little houses, at least some of which were reached by a wooden staircase.

In 1891, the City tore down the high school and built its second courthouse. The first courthouse was on Court Street. That imposing large red stone second courthouse building was the most impressive building in the City until 1928, when the present City Hall was built, an easy walking distance from Temple and Broadway. The Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center is at that location. City Hall is a little south of it. The United States Courthouse building occupies what had been the hill I believe Helen climbed. The Santa Ana freeway runs along the eastern-ish side of the federal building.

On the other side of the freeway and a little to the south stands the Pio Pico House, where Helen also stayed. The original plaza is on the east-north side of the Pio Pico House. Olvera Street, formerly Wine Street, is to the east of the plaza: “The present plaza of the city is near the original plaza marked out at the time of the first settlement; the low adobe house of one of the early governors stands yet on its east side, and is still a habitable building. “ The Avila Adobe, built in 1818 by Francisco Avila, still stands, restored after the 1870 earthquake. Francisco Avila was not a governor of Alta California. Pio Pico, however, was twice governor of Alta California (1832 and again 1845-46). Helen may have mixed up the history she heard.

In 1872, Helen could have easily walked from her previous lodging at the Pio Pico House to the western side of the hill that was once part of Pound Cake Hill. She fairly comfortably could have climbed that side of the hill and emerged on the North Broadway side of it. (Photograph four). The houses on its top would have had views of the orchards and vineyards to the south, the San Gabriel Mountains to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Today, a pound cake is often made in a Bundt cake pan, which is a circle with a hole in the middle but it is often also baked in a circular pan with a hole in the middle. The lynching photographs suggests the hill looked like a loaf, but early drawing of the city seen from the east side of the river shows Los Angeles High School sitting in what looks like a round lump. Victorian recipes indicate the baker should pour batter into spring form cake tins, which were round. The two shapes suggest that Pound Cake Hill, probably a round hill, was connected to a loaf shaped hill – Bunker Hill. k

The Stanley Mosk mailing address is 111 North Hill Street, a little to the north of the Fotlz Criminal Justice Center. I assume the street was named Hill because it went along the hill. Entering the Stanley Mosk on Hill, you enter the first floor of the courthouse. The courtrooms and offices don’t have windows. Judges’ chambers behind the courtrooms have windows. I have only been in one judge’s chambers, and I then had no interest in the view. If you take either the elevator or the escalator to the fourth floor, you exit the building on Grand, which is on Bunker Hill.

To capture the view that Helen described had go to the cafeteria on the ninth floor. You will then be at the approximate height of the top of the erased hill. If you go through the doors to the right side of the cafeteria as you come out of the elevator, you can see the Disney Music Center from one end, and the mountains on the other. If you go out the doors to the tables outside on the other side, and if the sky is as clear as it was before the invention of automobiles – maybe such a day rarely happens — you can see as far as Catalina Island.

Read:

http://stoltzfamily.us/2010/04/28/sonora-town-the-first-barrio-of-los-angeles/. (Retrieved May 11, 2014)

http://www.kcet.org/updaily/socal_focus/history/la-as-subject/the-lost-hills-of-los-angeles.html. (Retrieved July 5, 2014)

http://historylosangeles.blogspot.com/2010/02/lynching-of-lashenais.html.

(Retrieved July 5, 2014)

Jackson, “Bits of Travel at Home.”

http://www.cprr.org/Museum/Bits_of_Travel_at_Home.html .

Http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/bits_of_travel_at_home/to_ahwahne.html

(Retrieved May 11, 2014)

Jackson, “Echoes in the City of the Angels,” Glimpses of California and the Missions, 1886. https://archive.org/details/glimpsescalifor00jackgoog.

Jackson writing as Sax Holme. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10926/10926-h/10926-h.html (Retrieved July 6, 2014)

Antonio Coronel, “Tales of Mexican California,” Ed Doyce B. Nunis, Jr.

Edward D. Castillo, Native American Perspectives on the Hispanic Colonization of Alta California (1991)

Steven Hackel, Junipero Serra: California’s Founding Father (2013)

Dolores Hayden, Redesigning the American Dream (1984)

Valerie Sheres Mathes. (1990) Helen Hunt Jackson and Her Indian Reform Legacy. Page 40 has a map of the Indian villages Hunt visited.

Carey McWilliams, “Indian in the Closet,” Southern California: An Island on the Land. McWilliams took the title for his book from a comment by Helen Hunt Jackson. You can read this chapter on-line at: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/comm/steen/cogweb/Chumash/McWilliams.html

Douglas Monroy Thrown Among Strangers: The Making of Mexican Culture in Frontier California (1990)

Don Normark, Chavez Ravine. 1949. (1999). Mr. Normark took photographs of Chavez Ravine, previously Chavez Canyon, when he was a teenager. These wonderful photographs emphasize the lives of the people who used to live in the communities of Bishop, Loma Linda and Palo Verde. A good short history of what happened to these people, almost entirely people whose ancestors came from Mexico, as one of the results of the Red Scare triggered by powerful real estate interests can be read at http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/chavezravine/cr.html.

Ramon Guitierrez Ricard J. Orsi ( 1998) Edward Castillo and Robert H. Jackson, Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System.

Kate Phillips Helen Hunt Jackson A literary Life (2003)

Peter Reich (1994), Washington Law Review, volume 69, number 4. “Mission Revival Jurisprudence: State Courts and Hispanic Water Law Since 1850.” Professor Reich’s essay considers the mission revival cultural trope that began with Helen’s Ramona as an influence on legal doctrine.

Lionel Rolfe, Literary L.A. (Amazon just republished this as a paperback.)

David L. Ulin, Writing Los Angeles (2002)

Visit:

Angelino Heights

Angels Flight railway

Avila Adobe in Olvera Street

Elysian Park

http://www.publicartinla.com/Downtown/Broadway/Biddy_Mason/mason.html. The wall honoring Biddy Mason, established through the work of then-UCLA Professor of Urban Planning Dolores Hayden, stands behind the Bradbury Building in downtown Los Angeles.

Stanley Mosk Courthouse cafeteria

Pio Pico State Historic Park. http://www.piopico.org/.

Rancho Camulos Museum

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.