Honey and the mystery of El Portezuelo

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

[In order to see the detail of the maps and some of the larger photos, you can click on them to see the full size.]

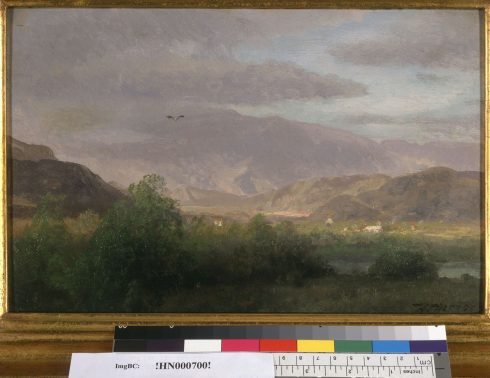

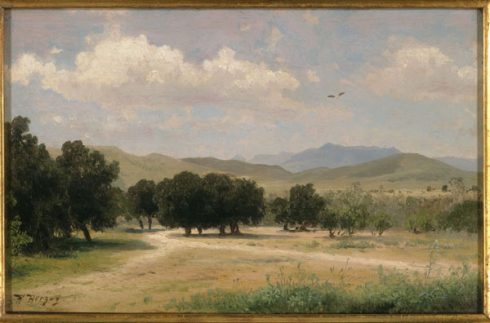

This is an untitled picture, but labeled by the Bancroft library as “a valley near Los Angeles.” It is dated circa 1870. Bancroft Library, the Robert Honeyman, Jr. Collection of Early Californian Art and Western Americana.

[A first part of this study appeared in this column on July 1, titled “Honey’s Search for El Portezuela.”]

A young sailor kept a diary of his voyage on the brig Pilgrim, published as a book in 1840 as Two Years Before the Mast.

The sailor – Richard Henry Dana – arrived in Alta California when it was a province of Mexico, and no longer a Spanish colony. He visited the small city of Los Angeles in 1835.

In his chapter “California and Its Inhabitants,” he wrote, “In the hands of an enterprising people, what a country this might be!”

Dana wrote what most people in the U.S. that had time to think about it believed: the United States should take the Mexican land in Alta California, and eventually, the United States did succeed.

The United States coveted California, even before gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. The term “Manifest Destiny,” coined in 1845, expressed an already existing philosophy that drove 19th century U.S. territorial expansion – the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire North American continent.

The democracy part was spurious. California was by then part of a large republic. They had as much democracy as had white men in the United States. Mexico had outlawed slavery in 1821. One of the California’s legislature’s first acts in 1850 was to pass a law legalizing the slavery of Indians.

California became a state in 1850, and Dana’s dream for California was realized. The more enterprising people had arrived.

The city government sold off its Spanish and Mexican legacy of open land and sub-divided it for sale. When it didn’t sell, the city gave land away to make the other plots more attractive. No provision for open space was made except for Elysian Park in 1886 – and that was because it was too steeply hilled to develop.

The enterprising people’s notion of land ownership took hold: land was to sell; its primary purpose was to be sold at the highest price.

Laborers from Mexico and China arrived as an aftermath of the Gold Rush, supplanting the legal slavery of Indians, providing an underpaid proletariat class.

The riverbed was plundered of its gravel, which had contributed minerals to the earth during floods, and industry contaminated it. The Southern Pacific Railway arrived, setting off a real estate boom. The boom didn’t last but the trolley system originally devised as a way to encourage development did, and, in time, brought more land in for sale.

Griffith J. Griffith donated Griffith Park – the largest part of his purchase of the Feliz Rancho – and complained that people cut down the oak trees for firewood.

The zanja system of water delivery established in Spanish Colonial days was abandoned at the turn of the twentieth century. William Mulholland engineered the aqueduct from the Owens Valley. Water was piped in from the Colorado River.

Oil wells pulled petroleum from the ground. The city built streets and bored tunnels through the hills. It excavated a route for Sunset Boulevard through one of the hills in 1909. It capped the springs and ran them underground in pipes as wastewater.

Automobiles changed the air quality and increased the distance from the city’s core where land could be divided.

The US Corps of Army Engineers deepened and widened the Los Angeles River and encased it in concrete so that the once clear flows of water went to the sea. Many people that live on the Westside don’t know there is a river; rather that there was a river. They don’t see the homeless encampments in the brush that grew through the soft bottom of the Glendale Narrows.

Freeways lengthened the reach of real estate developers at taxpayer expense. Fort Moore hill was excavated for the Hollywood Freeway. Old streets alongside it end in the freeway and sometimes take up again on the other side of it.

The orange groves with their vivid globes of fruit hanging from dark green leaves disappeared into subdivisions. One historic orange grove remains at the edge of California State University Northridge.

Until 1948, racially restrictive covenants divided Los Angeles into places where people of Mexican, Japanese, Chinese, and African descent and Jewish people were allowed to live and where they could not. South Los Angeles, for a time an African-American ghetto, increasingly home to people that arrive from south of the border, remains underserved.

If you take the Blue Line from downtown over those areas, you pass by faceless sweatshops, and – when the train is elevated – the small old houses have barred windows but you can see that once the neighborhoods were charming. If you drive through the south of Los Angeles, the impression is different: concrete, almost no trees, and little shade.

The city’s zoning law left the area below the SPPR railway station industrial, interspersed with the small homes of working people, and now a seemingly lifeless area of warehouses and parking lots.

If the Spanish explorers saw Los Angeles today, they would not know where they were. If people of our time were transported in a time machine to the Los Angeles of the Spanish explorers, we would not know where we had landed.

This essay’s hunt for one place in the unfamiliar country of Los Angeles as it was in the eighteenth century illuminates the transformation of the land at the hands of the enterprising people. It was El Portezuelo, a stopping point in February 1776 for Juan Bautista de Anza as he brought colonists for the San Francisco Presidio through Los Angeles and camped there on their way.

Professor H. E. Bolton of UC Berkeley began the search for El Portezuelo in 1909. By then, however, the landscape had changed so much that the pioneer of Spanish borderlands research and writing could not find it, or, if he did find it, had worked out the wrong way to get there.

The search for El Portezuelo might lead to reconsideration of the present enterprising peoples’ marketing of land and to rediscovery of the injustice done to the native people and from that to discovery of new ways of doing things so that Los Angeles may endure.

Ursula Le Guinn, daughter of Indian ethnology professor A.L. Kroeber, suggested that reconsideration of our modern world in her 1986 utopian novel, Always Going Home. She set her novel in the Bay area. Unsurprisingly — in that her father’s research and writing on the California Indians framed her vision – Le Guinn’s imagined future in this novel is drawn from California Indian life.

This treasure hunt for a place once called El Portezuelo leads through the lost landscape of the city to and through places that make up the shapes in our memories and in our dreams just before we wake. It takes those who live in Los Angeles to places they see every day.

The Anza expedition of 1775-1776

Spain began colonizing Alta California with the Portola expedition of 1769 to 1770. Colonies were established at San Diego and Monterey, with a presidio and Franciscan mission at each location. The Mission San Gabriel was established in 1771. In 1775, the fathers moved the mission to its present location. In 1776, the mission was not the sturdy building we see today. It was a remote outpost built with reeds and sticks, with a thatched roof.

Anza scholar Professor Vladimir Guerrero wrote: “Due to the coastal currents and prevailing winds, to sail north from New Spain to Alta California sometimes took twice to three times as long as crossing the Atlantic. Even the short distance from San Blas on the mainland to La Paz at the tip of Baja California could take two to three weeks.”[1]

In 1772, Juan Bautista de Anza proposed an expedition to Alta California to the Viceroy of New Spain, following a land route from Tubac Presidio, south of present-day Tucson Arizona. The King of Spain approved Anza’s proposal. Anza left Tubac on January 8, 1774, with three padres, 20 soldiers, 35 mules, 65 cattle and 140 horses. On the first expedition, an Indian that had fled the San Gabriel Mission – Sebastian Tarabal – guided the expedition.

Anza reached the San Gabriel Mission at its first location on March 22, 1774, and Monterey on April 19th. He returned to Tubac by late May. On October 2, 1774, Anza was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Anza guided a second expedition that got under way on October 23, 1775, and arrived at the second site of the San Gabriel Mission in January 1776. The second expedition included Franciscan Father Pedro Font, chosen for his services as a chaplain and for his ability to read latitudes. Anza, however, kept Font’s sextant for most of the journey. Font’s diary provided most of the description of the journey, and he prepared a map. Over 240 people, including women and children, accompanied this expedition. They took 695 horses and mules.

On February 21, 1776, this large expedition passed through Los Angeles, and they stopped to rest about five o’clock, just before the sunset.

Anza and Father Font both mentioned the name El Portezuelo in connection with the campsite.

The scholarly dispute over the location of El Portezuelo

Herbert Eugene Bolton in his five volumes of Anza’s California Expeditions (1930) placed El Portezuelo at the end of the last Griffith Park hill where the river begins its turn to the south – today’s John C. Ferraro Soccer Field.

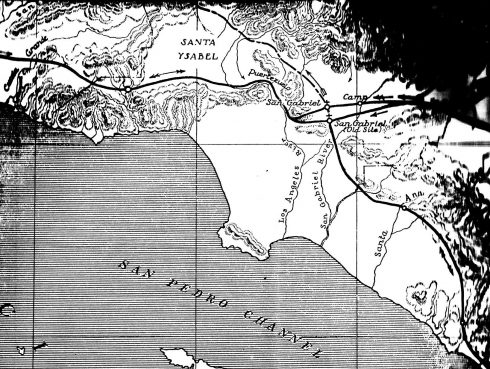

Bolton’s footnote 2 on page 105 of volume III of his Anza’s California Expeditions states, “The route was evidently along the line of the Southern Pacific Railroad through Alhambra to Los Angeles River, thence northwest up the river through the Portezuelo. Camp was at the turn of the mountains west of Glendale.”

Bolton’s map facing page 152, An Outpost of Empire,[2] indicated Anza stayed at the San Gabriel Mission then traveled north to “Portezuelo” along the river, which was not possible in 1776.

On this map, Bolton located “Portezuelo” at the edge of land at the bottom of the tall hill where the river bends and turns south – between the Santa Monica Mountains and the Verdugo Mountains, which suggests Bolton thought Portezuelo was the same thing as the Narrows – except that on page 359, Bolton wrote that El Portezuelo was near Glendale, which was and is on the east side of the river. His proposed site for the campsite was on the west side of the river.

Bolton stated Anza crossed the river, impliedly at the same place as Portola had crossed it, at the bottom of the Glendale Narrows, and then traveled upriver. There was no road going upriver from the Glendale Narrows because the Elysian Park hills descended to the edge of the river.

If Anza traveled to the site Bolton proposed in February then he traveled by some other route – a route that led through Yang-Na to another road that began at the western edge of the Indian village.

W.W. Robinson identified El Portezuelo as the site of modern Burbank.[3] This was Mariano Verdugo’s land grant, which was on the eastern side of the river and was called the Rancho San Rafael; however, Rancho Portezuelo was absorbed into the Rancho San Rafael, and he sold it to Mission San Fernando Rey in 1810. There is no indication in the journals that Anza crossed the river heading west and then re-crossed it to go back west to camp in Burbank.

Rancho Portezuelo was a 1795 grant. M. M. Livingston, in “The Earliest Spanish Land Grants in California,” states – without a footnote – that Rancho Portezuelo was in today’s San Fernando Valley.[4]

In 1871 Rancho Portezuelo was part of the San Rafael Rancho, also known as the Verdugo ranch. The San Rafael Rancho included Burbank, Glendale and La Canada cities. During that time Rancho Portezuelo was in the pass between the Verdugo Rancho and the Rancho Feliz, although separated by the river. (The Feliz Rancho also included an edge of today’s Burbank, and that area is in the San Fernando Valley.)

Vladimir Guerrero places the campsite in Glendale in his 2006 book, The Anza Trail and the Settling of California. As with W.W. Robinson’s theory that the campsite was in Burbank, the problem with this theory is there is no evidence in the journals that Anza crossed the Los Angeles River twice on February 21, 1776.

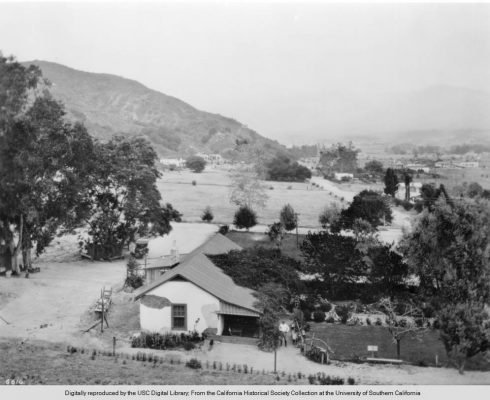

Following is a photograph of the Verdugo ranch house, built in 1860. The photograph is dated 1924 and shows the downslope of a Griffith Park hill (formerly part of the Feliz Rancho). The Verdugo family owned the land on the eastern side of the river that became Glendale, Glassell Park, Forest Lawn, and Lincoln Park. That was the San Raphael Rancho.

H.E. Bolton’s purported site is at the bottom of the hill in the background of this photograph.

Part of what is today Glendale was called Porto Suelo on the Verdugo Ranch, which means “I carry floor.” Before Glendale was named Glendale, the founding fathers of the town considered calling it Porto Suelo. Presumably, some of the founding fathers spoke a little Spanish, but the word “El Portezuelo” isn’t a word today’s native Spanish speakers recognize.

The photograph is significant in locating El Portezuelo because the similarity in names suggests that Bolton’s designation of the area where different creeks and washes joined the Los Angeles River may have been correct: all of the area along the Glendale Narrows was at one time Portezuelo.

The Anza Society concluded several years ago that Anza crossed the Hollywood Hills and camped in the vicinity of the studios, meaning Universal Studios, which does stand on a plateau once referred to as El Portezuelo de Cahuenga.[5] Robert G. Cowan, in Ranchos of California, sited “portezuela” (sic) at Universal City.[6] Jackson Mayers[7] also places Anza’s campground on the Cahuenga Pass. The Friends of the River guide to the Los Angeles River also places El Portezuelo as the Cahuenga Pass, “with the campsite along the river near present-day Universal Studios.”[8]

The reason for believing that Anza could not have camped at the site Bolton identified is because the land on the eastern side of the river in the Glendale area was marshy, and the mules could not have made it through, at least, not in February.

Bolton did not write that Anza traveled through today’s Glendale. Anza crossed the river at the regular place, a little over two leagues from the San Gabriel Mission, at the place where today’s Broadway Bridge stands, a tad below the bottom of the Glendale Narrows. An attack on Bolton’s position on the ground the soil was muddy in Glendale is an attack on a straw man.

The first governor of Alta California, Phelipe de Neve, passed through Los Angeles on his way to Monterey in 1777.

The governor’s biographer wrote:

“Neve himself, with reference to the Los Angeles area, complained that from the time of the first rains in November it was impossible to move the mule trains, and that ‘even counting on the rains stopping in February, the roads are impassable for more than a month afterwards.’”[9]

“The previous winter, that of 1776-1777, had been one of the driest yet experienced in California by the Spaniards.”[10]

The winter before that, presumably was one of the wet years with roads mules could not get through; nonetheless, Anza got them through the mud. He was a brilliant leader. Of course he would have taken the expedition along a relatively drier route, the route through Yang-Na eventually called El Camino Viejo.

The hills that surrounded Los Angeles in 1776 determined Anza’s route

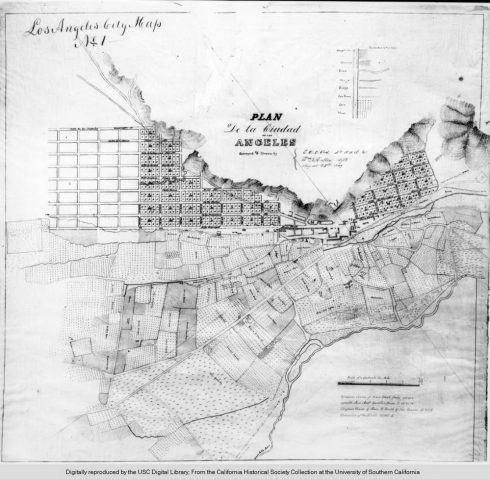

William Rich Hutton assisted E.O.C. Ord in making the August 1849 La Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles, the first survey of Los Angeles. The contract for the survey was for a map “two leagues to the four winds.”[11] The center of the map was the front of the church (completed in 1822). Ord’s compass “worked beautifully at first, but latterly it has proved less correct.”[12]

The copies of the map that exist do not show two leagues to the four winds. The map stops in the north at the top of the hills that embraced the small city. That hill was Fort Moore Hill, which no longer exists.

The map also does not go as far as the end of the Elysian Park Hills to the east, nor does it show the lands closer to the upper portion of the river nor the land below the Elysian Park hills.

A copy of the map found on the USC Digital Library is below.[13] There is no known original of this map.

Detail from E. O. C. Ord 1849 map of Los Angeles. The three-branching El Camino Viejo can be seen in upper left corner.

The small icon in the middle through which Ord or Hutton drew lines indicating north, south, east and west indicates La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, popularly called La Placita, completed in 1822. The nickname La Placita may have been a description of the small plaza once next to the church.

The area in the immediate area around the church is shown as empty. That area shows no plaza. The empty area was, by 1849, called “La Plaza.”

In 1836, the city’s ayuntamiento evicted the Indian people that were living in the open area. That empty area – and probably at the time of the Anza expedition a much larger area – was the Native American village of Yang-Na.[14] People that are today called Tongva lived in the Los Angeles area for at least 2,000 years – superseding an earlier Indian people.

Human beings lived in the area now the City of Los Angeles for at least 10,000 years. In 1959-1960, Phil C. Orr, curator of anthropology and Paleontology at the Santa Barbara Museum, excavated two femora and named them the “Arlington Springs Man.” His remains dated to 13,000 years ago.

No one knows how long Yang-Na was a central trading village, the wealthiest of the Southern California Indian people. The remains of “La Brea Woman” found in the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles in 1914, have been dated at 10,220-10,250 years ago. The village – at the junction of several Indian roads – may have been inhabited for a very long time.

As one comparison with the rest of the world, from about 11,500 years ago the eight Neolithic founder crops began to be cultivated in the Levant.

California’s Indians were hunter-gatherers at the time of Juan Bautista de Anza’s journey through Los Angeles in 1776. They were aware of Indian agricultural practices east of California: they traded with those people. Runners from the Mohave traveled about 60 miles a day – presumably on late spring and summer days when the sun rises earlier and sets earlier.

The Indian roads descended through the San Bernardino Mountains into the San Gabriel Valley and one crossed the Los Angeles River.[15]

On August 3, 1769, Portola and on February 21, 1776, Anza crossed the river at the same place: the part of the storm channel called the Los Angeles River spanned by today’s Broadway Bridge.

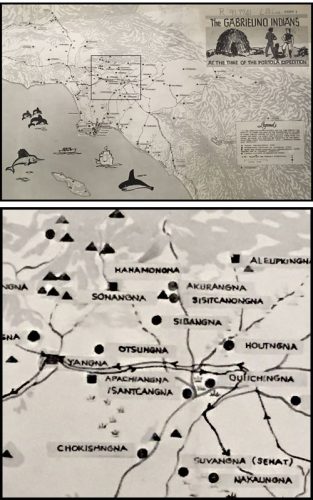

Bernice Eastman Johnston’s California Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum, Highland Park, 1962) contains a map of Indian routes through Los Angeles, but these routes seem partial, and in one place a village is in the wrong place. The map shows two routes across the river but there was only one: Father Crespi on August 2, 1769, saw the Arroyo Seco to the north.[16] He did not mention a second road just above the road Gaspar de Portola followed in 1769.

Detail from Bernice Eastman Johnston’s map of Indian routes through Los Angeles in The Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum, Highland Park, 1962).

The Ord map shows the road that heads to the northwest beginning on top of a small empty isosceles triangle. The triangle was to be reconfigured into a square in 1928. This area is where today’s City Hall stands.

This road traveled along the base of the hills, first as a street and then through the area with little squares, which was still, in 1849, undeveloped land. A creek passed, in the Ord map, down the north side of today’s Bunker Hill. That creek was to create a small park for about ten years, the Second Street Park, at the intersection of today’s First Street, Second Street and Glendale Boulevard.

The Ord map does not show that there was an arroyo almost immediately behind the hills, through which that same creek also flowed. The arroyo behind the hills was called after the Spanish occupation Arroyo de los Reyes. In 1868, it became Reservoir No. 4. It is today Echo Park Lake.

If you stand at the edge of Echo Park Lake nearest today’s Sunset Boulevard, by the 1930s statue Lady of the Lake, you see the skyscrapers that now stand on Bunker Hill.

As Ord’s compass was not working well, the lines depicting El Camino Viejo[17] may only be roughly correct.

El Camino Viejo continued, on the map, past today’s Figueroa Street, which then ended at the hills. The road split a little above Figueroa. One branch went in a westerly direction. That branch was for a time called El Camino de los Indios, the road the 1769 Portola expedition took past the La Brea tar pits to Santa Monica on August 3, 1769.

One branch continued a short distance and split again.

One of the secondary branches went along the hills towards the Cahuenga Pass. In January 1770, Portola returned to Los Angeles over the Cahuenga Pass.

The remaining road went through a pass in the hills. That branch is today’s Glendale Boulevard, which today runs alongside Echo Park Lake.

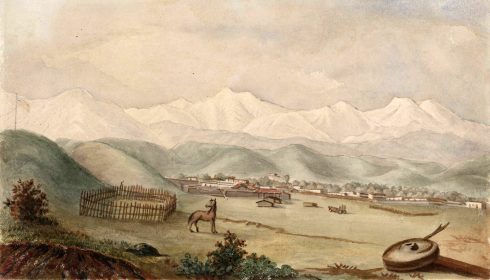

One of Hutton’s paintings shows the hills that he drew on the Ord map.

William Rich Hutton’s 1848 watercolor of the tiny Mexican city of Los Angeles showed the San Gabriel Mountains snow-covered in winter. The hill closest to the viewer is today’s Bunker Hill. The more distant hills are those that comprise today’s Elysian Park. The faint flag in the painting once flew over Fort Moore hill, which stretched from Temple Street to today’s Cesar Chavez Avenue.

The surrounding hills were tawny when Hutton painted them in August 1848. California’s hills are still green after heavy winter rains, and so they were most likely green in the winter of 1848.

During the millennia Indians lived in Los Angeles, however, those hills were blanketed with perennial native bunch grasses – also dark green in winter, but some green all year, some silver, silver blue, reddish green. Some of the native grasses flowered.[18] These were the hills the Spanish Colonial explorers, the Franciscan missionaries, and the first expeditions of Spanish settlers saw – Hutton’s hills, only before the Spanish and Mexican era occupants of Los Angeles brought sheep and cattle. Mediterranean (exotic) grasses now dominate California’s hills.

El Camino Viejo — roughly sketched in the Southwest Museum’s 1962 map called “The Gabrielino Indians at the time of the Portola Expedition” — shows the Cahuenga Pass route, the road to Santa Monica, and another road that headed east through the hills left of the village of Yang-Na at the time of the first Spanish Colonial land expedition in 1769.[19]

The detail of the Los Angeles area in the Southwest museum map shows the Portola expedition crossing the Los Angeles River a little above the confluence with the Arroyo Seco. Father Crespi in his journal wrote on August 2, 1769, that he could see the confluence of the Arroyo Seco with the river a little to the north of the crossing place.

Upriver on the detail are two or three Indian villages on the river and then an oblong marked Manamongna, probably the site of a village referred to elsewhere as Muhungna, which Eastman Johnston indicated was probably in the location of the Tujunga Wash.[20] The area delineated for Muhanga is large and vague. Comparing that area with a modern map, it looks as if Allen Welts drew the village in an uncertain area well below the Tujunga Wash.

The village of Yangna is designated on the Allen Welts map by a big square. From this map, it appears the Portola expedition – both on August 3, 1769, and later on the return trip in January 1770 passed through Yang-Na. This location corresponds with the Portola journal, which indicates the expedition traveled from the place they crossed the river about a half a league and they met Indians “on the road.” From Yang-Na headed north is a road with two branches. One of the branches goes to the north, presumably in the direction of the Cahuenga Pass. There is also a less well-delineated road headed north. Another road heads to Sonangna[21] and beyond that to Manamongna.[22] This is probably another pronunciation of Maawanga on what would be the Los Feliz Rancho.

The 1937 Kirkman-Harriman Pictorial and Historical Map of Los Angeles County 1860-1937, a copy of which may be explored on the Los Angeles Public Library website,[23] shows different routes through Los Angeles. The map is purportedly of Los Angeles in 1860. In 1860, there was no Yang-Na. The map shows, however, teepee icons representing other Indian villages, which also did not exist in 1860.[24] The Tongva people did not live in teepees.

The roads on the Southwest Museum map and the Kirkman map cannot be reconciled. Neither the Los Angeles Public Library nor the Huntington librarian in the text below its copy of the Kirkman map[25] show the sources George Kirkman and William Harriman used.

The road to Manamongna (in the Southwest Museum map) appears to have been reached by two routes: a path across hills, which looks like it started at about Solano Canyon, and the branching road from Yang-Na, which becomes less distinct after it passes through the hills.

Allen Welts – the artist that created the Southwest Museum map, seems not to have considered the 1849 E.O.C. Ord map/survey – La Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles — which showed the road from Yang-Na (“La Plaza” by 1849) starting as one road that separated into three, not two branches.

German-American artist Herman Herzog (1831-1932) arrived in California in 1873. He left the west in 1874. Much of the area behind the hills in the painting shown should have been included in the Ord map; whether the distance measured was one league or two leagues.

When Herzog painted his valley near Los Angeles paintings, those hills still embraced Los Angeles.

In 1873, Figueroa still stopped at the hills. In 1873, there was no Sunset Boulevard, although a portion of it may have begun as an Indian route.

Two of Herzog’s paintings were probably created in the area behind the hills.

Today’s neighborhoods of Belmont, Echo Park, Silver Lake and Los Feliz were behind the hills in Hutton’s painting. Angelino Heights is one of the hills behind Hutton’s hills. The Broadway tunnel (1901-1949), the Third Street tunnel (1901- ), the Hill Street tunnels (1909-49), and the Second Street tunnel (1924), bored through the hills. Dodger Stadium is in the hills nearest the river, the Elysian Park (1886) hills. Below the Elysian Park hills and along the river is Elysian Valley, better known as Frogtown. This area was agricultural by about 1860. After 1876, when Southern Pacific Railway reached Los Angeles, railway workers moved into the area, and it was then called Gopher Flats. The way for Sunset Boulevard dug through the hills in 1909. Fort Moore Hill was excavated for the 101 Freeway.

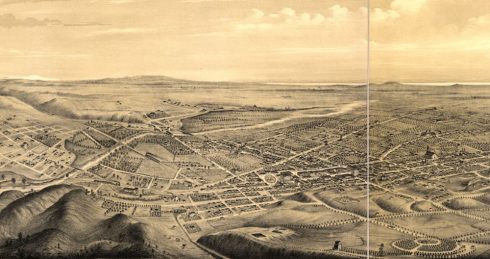

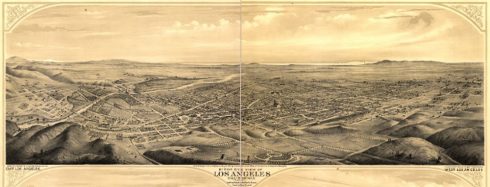

The map called “Birds eye view of Los Angeles, California”[26] from 1877, shows Los Angeles as mostly developed on the western side of the Los Angeles River. It appears the artist stood on the hills above Los Angeles to draw the map.

“Birds Eye View of Los Angeles, California.” Eli Sheldon Glover, Library of Congress. (A.L. Bancroft & Co. Lithographer, San Francisco, 1877) . Because of the unusually large size of the map and the limitations of computer screens we are present this map at three zoom levels to make the details more accessible.

The map is of Los Angeles as it was in 1877. Each of the three zoom levels can be clicked to see in more detail.

The long line of hills in the distance on the map marked the hills of the Palos Verdes Peninsula. The artist suggested the river with white.

In this “Birds eye view” of the city, trains – one marked “S.P.R.R.” – passed along tracks to and from the Southern Pacific Railroad River Station below the hills once called Stone Quarry Hills (Elysian Park after 1886).

The road behind the Southern Pacific train yard downtown started at the river and joined Alameda, which led into the plaza area.

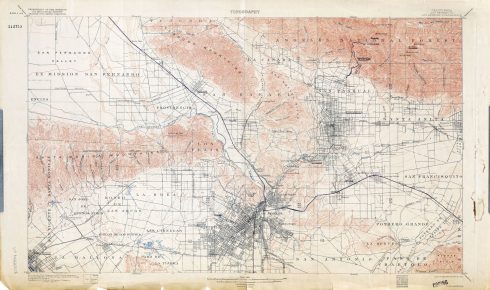

An 1894 topographical map shows Los Angeles County. The map is too large to copy here but it is on a collection of maps in the Perry-Castaneda Library Map, University of Texas Libraries. The link below opens to show a Los Angeles still only lightly developed behind the hills that loomed above the intensely developed downtown area.

This map can be clicked for a substantial enlargement. The actual map is far larger still and can be seen at the link in this paragraph. Perry-Castaneda Library Map Collection, University of Texas Libraries. http://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/topo/california/txu-pclmaps-topo-ca-los_angeles-1894.jpg The map is from the Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, George Otis Smith, Director. (Retrieved 8/15/2018)_

This map – a Department of the Interior USGS map — shows both Echo Park Lake and the tiny lake that once was fed by the same stream – both once arroyos through which flowed the same creek. In 1894 three creeks fed Reservoir No. 4 (Echo Park Lake). One creek emanated from where Baxter Street School in Echo Park is now. Another emanated from a spring on the other side of the hill – where Saint Teresa of Avila Church stands on the corner of Glendale Boulevard and Fargo Street, close to the 2 Freeway, and a short distance from where the Selig Polyscope Company – California’s first permanent movie studio – was built in 1909. Closer to Echo Park Lake was the Max Sennett studio, where Charlie Chaplin would begin his film career in Los Angeles in 1911. The silent film era corridor, ending in Tom Mix’s Mixville on today’s Glendale Boulevard and Teviot (now a shopping mall with a Starbuck’s and a 365 grocery store) was called Edendale.

The third creek that fed Reservoir No. 4 may not have been a natural creek but a ditch that zigzagged from the river. If it was a man-made ditch, it was dug in 1868, when Reservoir No. 4 was created.

The Department of the Interior topographical map shows the contours of the river before it was a storm channel. There seems to be no clear road from downtown to the Cahuenga Pass except by a streetcar line. This map shows there was a train track from the Southern Pacific Railway rail yard[27] that led a small distance at the base of Elysian Park and then crossed the river to go to the place marked Tropico.

The map produced by the Southwest Museum showed a footpath over the hills that were around Yang-Na. The 1894 topographical map suggests that footpath became the road dug into the Elysian Hills in 1860 for development in Solano Canyon. In 1894, that road meandered around in the Elysian Park hills but did not reach the Glendale Narrows.

In 1886, the Ostrich Farm Railway created a segment of today’s Sunset Boulevard (completed in 1909). Griffith J. Griffith’s Ostrich farm at today’s Crystal Springs picnic ground did not last long. By 1894, the topographic map shows the train line no longer went to Griffith Park but turned west at today’s Hollywood junction.

Any of the roads that reached the Glendale Narrows – if Anza went through the hills to reach the Glendale Narrows – that existed in 1894 may have started as Indian roads.

In 1894, a road could be followed from Echo Park Lake to the area that is today’s Frogtown. Another 1894 road went along what is today’s Glendale Boulevard through Edendale to the river at today’s Fletcher Drive.

In 1894, that road also turned at the bottom of what realtors call Waverly Heights and traveled along today’s Rowena past the “paper town” of Ivanhoe (subdivided, but not developed, during the Boom of the Eighties).

That road to Ivanhoe was near another spring that fed what was known as Sacatela Creek. The spring was capped in the early twentieth century, and the water run underground in pipes. John Marshall High School stands at that location. The Ivanhoe road continued in 1894 to join today’s Los Feliz Boulevard and, about a half a mile to the east was a large open area near the William Mulholland Memorial Fountain.

William Mulholland Memorial Fountain shortly after its opening in 1940 at the southwest corner of Los Feliz Blvd and Riverside Drive. This is from the Los Feliz Improvement Association site. https://www.lfia.org/historic-photo-display/.

Across today’s Riverside Drive is the Griffith Park Swimming Pool. Until the Golden Street Freeway cut into that flat portion of the park in 1960, there was a large flat area that ended in the Glendale Narrows. A children’s park with a today no doubt illegal carousel was located in that flat area. You could walk into the river from the children’s park until 1960.

That area was marked on an 1868 George Hansen map – “Rancho de los Felis: division line, Coronel and Lick Properties[28] — as “Puerta Suela.”[29] A place named El Portezuelo was on the Feliz Rancho. There is no map showing El Portezuelo anywhere else on the Feliz Rancho.

In 1894, there was a road from what was in 1868 “Puerta Suela” past Crystal Springs (Lago de Portezuelo in 1843, Crystal Springs picnic ground now) to the place H.E. Bolton posited as the location of the 1776 Anza campsite, which Bolton contended was El Portezuelo. The distance between “Puerta Suela” and Bolton’s site is 3.1 miles. The road from Puerta Suela today is Crystal Springs Drive until it reaches the Autry Museum, and, after that, the road is North Zoo Drive.

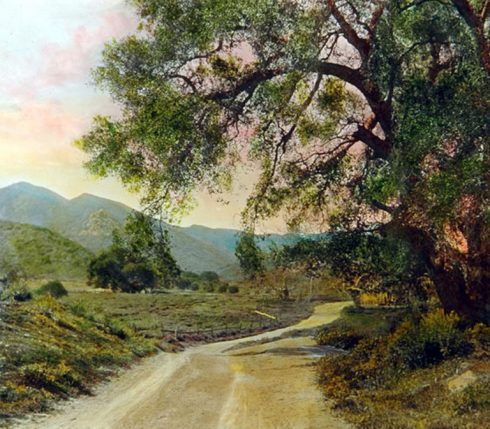

The photo is a lanternslide from the Los Feliz Improvement Association, id. It shows the road towards Crystal Springs in 1900.

Jose Vicente Feliz received the grant for the Feliz Rancho in about 1895. His rancho ended at the boundary to the City of Los Angeles’ “four leagues square.” Governor Micheltorena confirmed the grant to an heir in 1843.[30]

In 1775, Feliz joined the expedition of Juan Bautista de Anza to bring the San Francisco colonists to California. Along with his pregnant wife and eight children he departed from Tubac, Arizona in 1775. His wife died in childbirth on the road. He was to be one of the soldiers to accompany the settlers to the site of the first Spanish Colonial village in 1781.

Feliz knew the location of the place Anza and Father Pedro Font called El Portezuelo. For this reason, I feel the February 21, 1786, campsite was on the Glendale Narrows in the large grassy area opposite the Mulholland Fountain.

The Herzog painting at the beginning of this essay shows the San Gabriel Mountains above three or four hills: Herzog’s perspective was from the east. The afternoon light from the western sky dappled the leaves in the painting. The hills are not Hutton’s hills; rather they are hills behind Hutton’s hills. Two paths join to form a path through oak trees.

Anza passed through Los Angeles in February, when the hills were green. The hills would have been greener in 1776 at any time of the year, for the climate then in Los Angeles was wetter and colder.

The Los Angeles River in the second Herzog painting is probably the length of blue color near the right side in the second painting of a valley near Los Angeles. The San Gabriel Mountains appear closer in this painting. The pyramid shaped hill may be Mount Washington.[31]

If Anza in 1776 did not travel to the place on the Feliz Rancho named El Portezuelo, then he could have traveled up to where Franklin and Cahuenga meet – also on a branch of El Camino Viejo – and then over the hill down to the plateau of land where Universal Studios is today.

W.W. Robinson, in “Parade out of the Past,”[32] reported an interview with an elderly resident of Los Angeles, which described an 1868 parade over El Camino Viejo from the old Encino ranch house in the San Fernando Valley:

“A great plain spread out before us where now Hollywood and Los Angeles lie. No buildings or houses in sight – just a green plain covered with alfilaria grass and with cattle of the ranches grazing. We went in the direction of the tar pits area, and then came in on the old highway. We crossed the thin alkaline stream that has since been made into Westlake (now MacArthur) Park, and continued on the road that curved toward the pueblo. It followed the lines of least resistance and coincided in part with the present Wilshire Boulevard, skirted the base of hills that we almost forget exist….” (Alfilaria grass is a European weed grown for forage in the dry regions of the southwestern United States – also called pin grass.)[33]

W.W. Robinson identified the beginning of El Camino Viejo as “the old highway that in pueblo days passed just south and west of the new Statler Hotel site.” Robinson wrote this essay in 1952. The Statler was demolished in 2013. The Wilshire Grand Tower replaced it and its address is 900 Wilshire Boulevard. Below is a photograph of Wilshire Boulevard and Grand Avenue in 1948.

Wilshire Boulevard and Grand Avenue, 1948. Photograph courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library. Most of the buildings in this photograph have been demolished.

Juan Bautista de Anza wrote about February 21, 1776:

“At half past eleven, when everything was ready for the march, I set forth with seventeen of the soldiers and the same number of the families destined to remain in this California, besides six of my company. Four of these last are remaining here to await Lieutenant Moraga, as has been said, also to escort the cattle belonging to the colonists. I set out on the regular road to Monte Rey, which we followed for a little more than a league to the southwest. Continuing for another league to the west-southwest, we crossed the Porciuncula River. After this we made three more leagues, traveling until five o’clock in the afternoon, having marched five and a half hours, when we halted at El Portezuelo, where the night was passed. Notwithstanding that for a number of days past it has not rained very hard, the road has been so heavy that many of the mules which carried the loads fell down.”[34]

Alan K. Brown translated and edited the journal of Pedro Font, O.F.M.[35] Brown depended in part on the discovery by Spanish Franciscan historian Luis Soto Perez, who published a manuscript that was the actual draft journal that Font wrote during the course of his travels.[36]

Father Font wrote:

“[February] 21, Wednesday, I did the blessing of ashes; I said Mass, and during it four words to the people who were remaining and to the rest of them who were going (who wept a bit since they regretted this separation), by using the gospel of the day to reaffirm what I had been saying to them in the talks I gave them. That is, that they had come in order to suffer and give an example of Christianity to the gentiles, etc., the whole of it amounting to exhorting both groups to repent for their faults and patience in hardship, etc., etc. We went out from Mission San Gabriel at a half past eleven in the morning and halted at a half past four in the afternoon at the spot called El Portezuelo having traveled for five leagues following a west-northwestward course with some veering to one side and the other. At two leagues we crossed the Porciuncula River, which carries a good amount of water and runs toward the San Pedro bight, and spreads out and loses itself upon the plains shortly before reaching the sea. The land was very green and flowery and the route had a few hills and a great deal of miry grounds created by the rains. This is why the pack train fell far in the rear.[37] At the stopping place there is year-round water, although little of it, and sufficient firewood. As one goes along, far off on the left hand, upon the sea, lies the hill range forming the San Pedro bight, and on the right rises the snowy range, with another steep, steep range lying in front of it.”[38]

The “snowy range” was the range of the San Gabriel Mountains. Official records of snowfall in Los Angeles began in 1877. Measureable snow fell in downtown Los Angeles in 1882, 1932 and 1949. The last time snow fell somewhere in the Los Angeles basin was in 1962. Los Angeles is roughly five degrees Fahrenheit warmer than it was a century ago.[39] Snow, however, sometimes still covers the tops of the San Gabriel Mountains. The smaller “steep sided” range was the Verdugo Mountains.

A “bight” is a curve or recess in a coastline, river or other geographical feature. It typically indicates a large, open bay. Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo discovered the bay that would be known as San Pedro in 1542. Font did not see the bight itself from wherever it was that he stood; rather, he saw a hill range that formed the bight “far off on the left hand, upon the sea.” He was probably looking at the Palos Verdes peninsula.

Font and Anza agreed the expedition traveled two leagues to the Los Angeles River and that they crossed the river. Two leagues — if they measured the distances as they traveled — was 7.2 miles. The shortest distance on “the regular road” – the road Portola took before the mission was established — on today’s roads is 8.1 miles.

That discrepancy suggests that neither Font nor Anza measured the distance but that they estimated it. Another measure of the Spanish Colonial league was the distance a horse traveled walking in one hour. Fresh from a respite at the mission to the river, they traveled, then, two hours.

Their total distance was about five leagues from the mission to the stopping place. That translates to a total distance of 18 miles. If they did not measure the distances but estimated them they traveled for three hours after crossing the river.

Font wrote that they stopped at half past four in the afternoon – five hours of travel including the mules stuck in mud. Anza wrote they stopped at five in the afternoon. That is, they traveled at a pace measured by the horses for between five and five and a half hours, not that they traveled exactly 18 miles.

Although Bolton described Anza’s first trip through Los Angeles as one that went through a much different landscape, Anza’s familiarity with the route he took in 1776 indicates he had been through there previously. Sebastian Tarabal either guided him on the first trip or the guide interpreted the language of the local people so that Anza would understand the roads.

Bolton placed El Portezuelo at the location where the Los Angeles River turns south at the top of the Glendale Narrows. That location corresponds to one meaning of el portezuelo.

According to Josiah D. Whitney:[40]

“The summit of the pass is called the divide or water-shed. In this last word the ‘shed’ has not the present meaning, but an obsolescent one of ‘part’ or ‘divide’…. Skeat says: ‘The old sense to part is nearly obsolete, except in water-shed, the ridge which parts river-systems….The ‘water-shed’ of any river basin limits its ‘area of catchment,’ as the hydraulic engineers call it.” Portezuelo, also spelled ‘portachuelo,’[41] is the Spanish for ‘divide’ and this word is – or was, a few years ago – in current use among English-speaking people in parts of the California Coast Ranges.”

When Anza wrote “when we halted at El Portezuelo…” he may have meant Bolton’s designated location.

Another interpretation is that the expedition halted at the western bank of the Glendale Narrows. Bolton’s remark that Anza traveled up the river along the western side of the Glendale Narrows is based on a belief there was a road from the regular crossing place along the river all the way to the top of the Glendale Narrows.

In 1860, there was no road. A short distance above the fording place, the Elysian Park hills came down to the river, blocking a route for over 200 people and their animals to pass.

Frogtown, also known as Elysian Valley. Bordered on the north by Atwater Village, on the northeast and east by Glassell Park, on the southeast by Cypress Park, on the south and southwest by Elysian Park and on the west and northwest by Echo Park and Silver Lake. The Los Angeles River is on the north and east, Riverside Drive on the west and Fletcher Drive on the northwest.

Assuming Anza followed the same road as Portola had followed seven years earlier, Anza also traveled 1.8 miles from the crossing place to the beginning of the ancient Indian road called eventually El Camino Viejo.

As may be seen from a detail of the 1849 E.O.C. Ord/William Rich Hutton La Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles, a road left the by-then plaza area and traveled north. One branch went towards Santa Monica. That’s the branch Portola followed in 1769. One branch went towards the Cahuenga Pass. The Portola expedition returned in January 1770 to Los Angeles by the Cahuenga Pass route. Father Font wrote they traveled “following a west-northwestward course with some veering to one side and the other.” This suggests the Anza expedition traveled to Yang-Na, then northwest – the Cahuenga arm of El Camino Viejo.

On the other hand, Font also wrote “and on the right rises the snowy range, with another steep, steep range lying in front of it.” He could have seen the San Gabriel Mountains when they crossed the river. He only had to have looked behind him. He could not, however, have seen the “steep, steep range lying in front of it” except from a place along the Los Angeles River. He could not have seen the Verdugo Mountains from the Cahuenga Pass, nor could he have seen the Verdugo Mountains from a Universal Studios location.

What does Portezuelo mean?

In the 17th century, Miguel Cervantes mentioned a portezuelo in Don Quixote, which a translator interpreted as “a gate.”

The meaning of the word, however, may be quite a bit older than the passing reference in Don Quixote. Old Castilian or Medieval Spanish was originally a colloquial Latin spoken in the provinces of the Roman Empire that provided the root for the early form of the Spanish language that was spoken on the Iberian Peninsula from the 10th century until about the beginning of the 15th century.[42]

“Porte” in Latin means “the gates.” The suffix “zuelo” in Spanish is the same as “-uelo. It also is of Latin origin.”[43] Taken literally – if it may be taken literally because languages morph and it is an archaic word – the word could have meant gate. The “zuelo” part does not translate well but adds a value that could be derogatory, relate to affection, or mean small.

The “Compilation of Colonial Spanish Terms”[44] does not list Portezuelo as a Spanish Colonial term. Portachuelo, however, is a contemporary Spanish word for a gap opened in the convergence of two mountains. The etymology of the word portachuelo in a Spanish dictionary is listed as portichuelo, and porticuelo is “Puerto bajo en las estribaciones de una montaña. (Low port in the foothills of a mountain)

The modern dictionary’s explanation of the origin of “portezuelo” may be imprecise; at least, as there was no port at the foothills of a mountain in the Los Angeles area except for the San Pedro harbor, which wasn’t really port in 1776, and wasn’t actually in the foothills of a mountains. Ships moored, however, in the Bay of Smokes during the Spanish Colonial period, and Font referred to the bight of San Pedro in his diary.

A nineteenth century land claims survey referred to the Portezuelo as an opening or gate through which a road passed.[45]

Anza wrote, “After this we made three more leagues, traveling until five o’clock in the afternoon, having marched five and a half hours, when we halted at El Portezuelo, where the night was passed….”

Anza could have meant the expedition reached the Glendale Narrows and stopped.

Blake Gumprecht described the river:

“The river as it is now recognized meandered east along the base of the Santa Monica Mountains through present-day Universal City and Burbank before turning southeast near Griffith Park, where it followed the eastern terminus of the mountains. Verdugo Wash and the Arroyo Seco, dry most of the year, added to its flow during winter months. The river reached the coastal plain via a gap between two hills known as the Glendale Narrows, the San Fernando Valley’s only outlet to the sea, so named because the hills on both sides of the river come progressively closer together farther south until they are but a few hundred yards apart near Elysian Park…..The river through this section provided all the water needed by the city of Los Angeles for more than a century.”[46]

If Anza meant the expedition halted at “a gate” between mountains, that also did not mean El Portezuelo de Cahuenga: the Cahuenga Pass is a saddle of land through one mountain range. Font wrote that there were “a few hills” on the road to the campsite. The road on El Camino Viejo to the Cahuenga Pass was on a plain.

Bolton’s proposed location could be interpreted as a gate or a gap; it was at the end of the Santa Monica Mountains and on the other side stood the Verdugo Mountains.

The gate or gap between mountains could have meant the gap between the steep Stone Quarry hills (Elysian Park) and the Santa Monica Mountain Range. If that was the gap, then El Portezuelo on the Feliz Rancho was Anza’s El Portezuelo.

There were hills on the route through the hills on the branch of El Camino Viejo that went east through a pass in the hills to Arroyo de los Reyes (today’s Echo Park Lake): Angelino Heights, the Echo Park hills, the Silver Lake hills, and the once continuous hill once called “Waverly Heights.”

Conclusion

The mystery of El Portezuelo is that it was lost. The archaic name most likely referred to the entire area through which the Los Angeles River is narrowed by hills before reaching the plain, beginning at the last hill in today’s Griffith Park; this is, the area we call the Glendale Narrows.

Geography determined Anza passed at the bottom of the Narrows, traveled through Yang-Na and went either to the Universal Studio site or to the place later called El Portezuelo on the Feliz Rancho; that is, the area around the Griffith Park Swimming pool and the Mulholland Fountain, but, really, probably the area that is under the Golden State freeway where the river swung out creating land from which Father Font could have stood and seen the Verdugo Mountains.

The shortest distance using today’s streets from the Broadway Bridge crossing area, assuming Anza went through Yang-Na – he had to have – to Universal studios is 3.72 leagues.

The distance to El Portezuelo was 2.694 leagues.

[1] Vladimir Guerrero, The Anza Trail and the Settling of California (Heyday Books, 2006), p. xii.

[2] Herbert Eugene Bolton, Anza’s California Expeditions, Volume 1, An Outpost of Empire (University of California Press, Berkeley, California 1930).

[3] W.W. Robinson, Land in California: The Story of Mission Land, Ranches, Mining Claims, Railroad Grants, Land Scrip, Homesteads, Tidelands (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1948), page 50.

[4] M. M. Livingston, “The Earliest Spanish Land Grants in California,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California (1914), pp. 195-199, at page 199.

[5] Email exchange from Joe Myers, Anza Society, August 7, 2018.

[6] Robert G. Cowan, Ranchos of California, a List of Spanish Concessions, 1775-1822, and Mexican Grants, 1822-1846 (Fresno. California, Academy Library Guild, 1956), p. 62. Cowan defined Portezuela (sic) as a land grant to Mariano de Luz Verdugo in 1795, Cowan did not cite his authority. He wrote that it was once part of the Verdugo Rancho. There were two Verdugo land grants in that area.

[7] Jackson Mayers, Burbank History (James W. Anderson, Burbank, California 1975)

[8] Joe Linton, Down by the Los Angeles River: Friends of the Los Angeles River’s Official Guide (Wilderness Press 2005), page 94.

[9] Edwin A. Beilharz, Felipe de Neve: First Governor of California (California Historical Society, San Francisco 1971), page 100. Neve himself spelled his name Phelipe. Some sources list him as the fourth governor of Alta California. The first three were military commanders before civil administration was established.

[10] Id, page 101.

[11] William Rich Hutton, Glances at California 1847-1853 (Diaries and Letters of William Rich Hutton, Surveyor, With a Brief Mem

oir and Notes by Willard O. Waters) (The Huntington Library, San Marino 1942), page 16. Elsewhere, Hutton wrote “By tradition they are entitled to four leagues square, but there is no law or title in this part of the country to show the right to a yard of ground, except the ordering this establishment, which specifies nothing.” (page 15). Also, “We go from the hills to the river & from the grave yard as far as the last house south of town… in addition, we are to measure 4 leagues, north, south, east & west of the church, & mark the corners as those of the town lands.” (pages 17 and 18)

[12] Id, page 13.

[13] http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15799coll65/id/12770/rec/2. (Retrieved 8/23/2018)

[14] Yang-Na is the most commonly used name for the village.

[15] John W. Robinson, “Winged Feet in the Dust: Long-Distance Trade Routes in Aboriginal California.” The California Territorial Quarterly, Number 52, Winter 2002, pages 4-17. See, James T. Davis, “Trade Routes and Economic Exchange Among the Indians of California,” Aboriginal California Three Studies in Cultural History (The University of California Archaeological Research Facility, second printing 1966).

[16] Allen Welts drew the map. The work was based on a number of sources: A.L. Kroeber’s map of California Indians; Thomas Workman Temple II provided items from early California records in the Bancroft Library, Dr. Gerald Smith, director of the San Bernardino County Museum, and Don Meadows, of Santa Ana, contributed notes from their firsthand archeological studies. The Department of Water and Power, City of Los Angeles, traced ancient waterways. ( Carl S. Denzel, Director, Southwest Museum, July 1962, forward in Bernice Eastman Johnston’s California’s Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum 1962)), pages iii to vi.

[17] The entire three-branched route was, at one time, called El Camino Viejo. In time, historians referred to the branch Leo Carrillo, in his autobiography and recollection of early Californio stories, referred to as Calle de los Indios became thought of as El Camino Viejo. See, Leo Carrillo, The California I Love (Prentice-Hall 1961). El Camino Viejo at one or two of its northern termini probably connected with the road through the Central Valley called El Camino Viejo a Los Angeles.

[18] See, Sheila Barry, Stephanie Larson, and Melvin George, “California Native Grasslands: A Historical Perspective.” Grasslands, Winter 2006.

[19] Allen Welts drew the map. The work was based on a number of sources: A.L. Kroeber’s map of California Indians; Thomas Workman Temple II provided items from early California records in the Bancroft Library, Dr. Gerald Smith, director of the San Bernardino County Museum, and Don Meadows, of Santa Ana, contributed notes from their firsthand archeological studies. The Department of Water and Power, City of Los Angeles, traced ancient waterways. Carl S. Denzel, Director, Southwest Museum, July 1962, forward in Bernice Eastman Johnston’s California’s Gabrielino Indians (Southwest Museum 1962), pages iii to vi.

[20] Bernice Eastman Johnston, Id, page 126.

[21] The only reference to Sonangna is in San Marino County, so this might be a mistake in the map. See, Eastman, page 164. William McCawley, The First Angelinos (A Malki Museum Press/Ballena Press Cooperative Publication, lists Sonaanga near the San Gabriel mission, citing Hugo Reid but a similarly named place in a ravine where the Old Los Angeles crossed the river. Page 41).

[22] William McCawley, Id, mentions the village of Maawagna on the Feliz Rancho, at page 55, upriver from Yang-Na on the other side of hills. See Map 9, facing page 57, of McCawley’s book.

[23] http://tessa.lapl.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/maps/id/29/rec/2. (Retrieved 8/16/2018) A more complete map – but harder to see – is on the Huntington Digital Library. http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15150coll4/id/1536. (Retrieved 8/16/2018).

[24] The padres of the San Gabriel Mission (1771) and the San Fernando Mission conscripted the Tongva people. Largely as a result of confinement in the missions, more of California’s mission Indians died than were born. The contagious illnesses included small pox, measles, pneumonia and syphilis. The non-Indian settlers and non-mission Indians also died, but the native people had no immunities to these diseases. See, Sherburne F. Cook, The Conflict Between the California Indian and White Civilization (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California 1976), pages 197 to 226. The government in Mexico City secularized the missions in 1834. Little of the mission lands went to the Indians. The mission Indians that remained had no villages left. Some of the Southern California Indians went to Yang-Na, which remained until 1836. The remaining Indians relocated to a created village, La Rancheria de los Poblanos, where they remained for ten years until the Dutch immigrant re-named Juan Domingo – who married one of the Feliz heirs – successfully petitioned for that land so he could establish a vineyard. The former residents of Yang-Na moved across the river to another created village – El Pueblito – a community that lasted two years. See, e.g., W.W. Robinson, The Indians of Los Angeles: Story of the Liquidation of a People (Dawson’s Bookstore 1952).

[25] http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15150coll4/id/1536. (Retrieved 8/23/2018.

[26] “Birds Eye View of Los Angeles, California.” Eli Sheldon Glover, Library of Congress. (A.L. Bancroft & Co. Lithographer, San Francisco, 1877) https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364l.pm000260/?r=-0.086,0.115,0.389,0.168,0. (Retrieved 7/19/2018).

[27] SP arrived in Los Angeles in 1876 and acquired a large portion of what was before that agricultural land. The Los Angeles State Historic Park occupies the former rail yard, and a sign in the park indicates its popular name – the Cornfield – probably has no connection to an actual cornfield. This area, however, is in the same area designated as the suertes – agricultural plots – in the copy of the 1786 Jose Arguello map of the first Spanish Colonial village, established in 1781. The original of the map was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco, but H. H. Bancroft sent a team of his researchers to the Provincial Archives, and one of them copied the Arguello map by hand.

[28] “Rancho de los Felis: division-line, Coronel and Lick properties,” http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15150coll4/id/11395/rec/7. (Retrieved 6/17/2018)

[29] In Spanish, puerta means door and suela means the sole of a shoe.

[30] Mitcheltorena Street in the Silver Lake District goes up a steep hill. Although the street appears on an 1880s subdivision map, it does not appear on the 1894 map.

[31] The Bancroft listing states the blue area is an arroyo. There were two arroyos through which the same creek flowed in this part of Los Angeles. One was Arroyo de los Reyes but this became Reservoir No. 4 in 1868, and it is now Echo Park Lake. The second arroyo was at the intersection of First Street, Second Street and Glendale Boulevard. This became for a short time Second Street Park. The perspectives seem wrong for both of these watery areas to be the light blue image.

[32] W.W. Robinson, in “Parade out of the Past.” Historical Society of Southern California, Volume XXXIV December 1952, Volume 4, p. 306

[33] By the “old highway,” the narrator seems to have meant the main branch of El Camino Viejo, also called “Calle de los Indios,” that led to Santa Monica. If he left Encino, he may have come over the Sepulveda Pass. It sounds as if he did because they went in the direction of the tar pits and then reached MacArthur Park, then a thin alkaline stream.

[34] Herbert E. Bolton, Anza’s California Expeditions, Volume III (University of California Press, 1930). page 107, “Anza’s Diary.”

[35] Alan K. Brown, translator and editor, With Anza to California, 1775-1776: The Journal of Pedro Font, O.F.M. (The Arthur H. Clark Company, an imprint of the University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma 2011).

[36] Id, page 9.

[37] Mule hooves are smaller than horse hooves.

[38] Brown, page 215.

[39] Nathan Masters, “Why Doesn’t It Snow in L.A. Anymore?” KCET. Lost L.A., December 9, 2016. https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/why-hasnt-it-snowed-in-los-angeles-since-1962. (Retrieved 6/10, 2018).

[40] Josiah D. Whitney, Names and Places Studies in Geographical and Topographical Nomenclature (Cambridge University Press 1888), page 141.

[41] Portachuelo today means an opening between two mountains, a pass, or a gap.

[42] Ralph Penny, A History of the Spanish Language (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom, first published 1991, Second edition 2002), pages 2-9.

[43] “Sufijo de origen latino que aporta un valor diminutivo y afectivo o despectivo.”

[44] Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold, “Compilation of Colonial Spanish Terms And Documented Phrases” (SHHAR Press, Midway City, California), copyright 1998). http://www.somosprimos.com/spanishterms/spanishterms.htm. (Retrieved 7/12/2018)

[45] “Private Land Claims,” page 1431, Miscellaneous Documents of the Senate of the United States 1878-’79. Page 1431.

[46] Blake Gumprecht, The Los Angeles River: Its Life, Death and Possible Rebirth (The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore & London, 1999), pages 15 and 16.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.