DENIS JOHNSTON ON SHAW

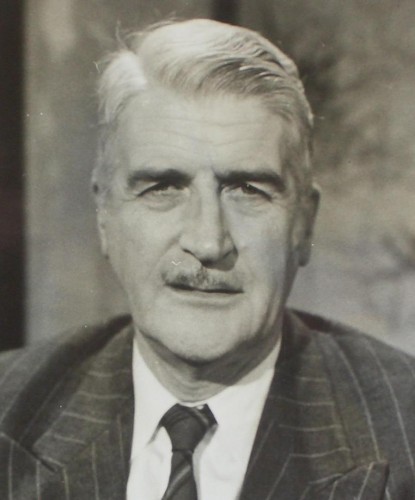

Denis Johnston was an Irish playwright who knew George Bernard Shaw and wrote about him. This article was compiled and edited by his son Rory Johnston, who works as a wire service editor in Los Angeles. Johnston (1901-84) was the last of the generation of Sean O’Casey, Micheál MacLiammóir, Barry Fitzgerald, F.J. McCormick and others who brought the Irish theatre its world-wide fame. He was a protégé of Yeats and Shaw. His first play The Old Lady Says “No!” took Dublin by storm in 1929 with its extraordinary originality and put the Dublin Gate Theatre on the map. His second play The Moon in the Yellow River (1931) established his international reputation. It has been performed on many stages around the globe in five different languages and in various mediums, its cast including such names as Jack Hawkins, Errol Flynn, James Mason, Claude Rains, and James Coco.

When I was a schoolboy in Dublin I went to the Abbey Theatre one evening expecting to see an amusing play by Lady Gregory called The Workhouse Ward. I was disappointed to find there had been some mistake, and that instead I was in for a debate between a fat man called Chesterton and a thin man called Shaw. What the subject was I don’t remember, but the fat man was very bluff and jolly, and tried to raise a laugh at the expense of the thin man by praising drink and overeating and good living generally. But then the thin man got to his feet.

“My friend,” he said, “always reminds me of a piece of music we’ve all heard, called The Merry Peasant. You know how it goes: Ta-ra, Ta-ra, Ta-ra-ra-ra-ra-ra…” With that he brought down the house. In that moment I decided that Shaw was all right, and I have never had any occasion to change my opinion.

In 1934 my play The Moon in the Yellow River had been produced in Dublin and New York but not in England. It had had what the agents call a mixed reception; it was appreciated by half the critics and cursed by the other half. The publicity for the play consisted of the publication in parallel columns of opposite views by the critics. The first production at the Abbey Theatre had received a good notice in the Irish Times, so I sent the notice to Bernard Shaw and asked if I could see him. To my great surprise I was invited to lunch.

Whitehall Court had the National Liberal Club at one end and Shaw at the other – a very natural progression from right to left, or the reverse, whichever way round you chose to look at it. The one has been described as the only club in London with a smokeroom in the tradition of Euston Station. The other was the only playwright in the world who could tell the film industry that he would not have his plays improved upon by script hacks. I speculated upon this as I went up in the lift, and was shown into his well-windowed sitting-room overlooking the river and the excavated palace of the Stuarts. As I looked around me, I noted the bust of Shaw by Rodin, and the portrait of Shaw by Augustus John, and the statuette of Shaw on the occasional table. Then I came to the book lying in state on the main table, and I noticed with deepening emotion that it was the Complete Plays of Bernard Shaw. I said to myself, I know exactly what’s going to happen – the same thing that always happens with far more modest celebrities – Fair Words, a little polite encouragement, a patronising pat on the head, and then – the door. That would be all.

Then he came in. I suppose that he really wanted to hear a bit of gossip about the Abbey and some of his acquaintances there, because this is what our conversation turned on to begin with. From this we went on to talk about his own work – on how Dubliners were taking John Bull’s Other Island these days and did they appear to like Major Barbara? I was also lucky in being in a position to tell him how Caesar and Cleopatra was being handled in Vienna, and what I had thought of Winifred Lenihan as Saint Joan in New York. None of this was tactically planned on my part, and it interested me as much as him. We discussed how he was proposing to rewrite Cymbeline, and the row with the Lord Lieutenant over Blanco Posnet. He was charming and it was all delightful, and it was not until I was going down in the lift that I suddenly realised that the one thing we had never mentioned was my beastly play. I tried to stop the machinery and go back, but it was no use. I’d been shanghaied and I knew it. I’d been sold down the river by a lot of interesting conversation and I hadn’t even had my quota of Fair Words.

But here’s the funny thing about Shaw – the thing that made his good works so different from anybody else’s. He promised nothing; he gave no honeyed phrases; he didn’t condescend to encourage me. In fact, so far from being encouraging, Shaw’s usual line with authors was that anybody who aspires to be a writer and needs encouragement had better be discouraged. But that summer, for no apparent reason, my play was being produced by Barry Jackson and the Birmingham Rep. company at the Malvern Festival, where Shaw was the King Pin. I don’t say why, and I don’t know why. Maybe it was just a coincidence. But it is the kind of coincidence that happened in the orbit of Shaw, and if I have to choose between that and the more usual form of encouragement, I know which I prefer every time. Indeed the only comment I ever got from Shaw on any of my work was a postcard which said rather peremptorily: “Why don’t you write more plays?”

Shaw to my mind more than anybody else is at the root of the ways of thinking that dominate the English-speaking communities of today. I say this from some experience in teaching his works to young people. I can remember the time, reading his prefaces at the age of twenty, when I thought that he was just trying to be perverse or funny, and making up my mind not to allow him to irritate or confuse me. Then a few years later, I passed through a sort of conversion to Shaw and accepted him as a prophet, pointing the way to a new and better state of Society. Now I find that a younger generation who are still going to and enjoying his plays find nothing odd or difficult about them. They take his views as a matter of course, and indeed often speak of them as rather old-fashioned and obvious. We live in fact in a Shavian world – with Shavian education, Shavian economics, a Shavian view of sex and marriage, and certainly a Shavian attitude towards religion.

I found him to be a very friendly person, once you set his mind at rest that you were not trying to get anything out of him. Indeed until his last days when he had become a sort of world figurehead, he was rather like one of those showing-off schoolboys that we all know who love to propound riddles and conundrums and laugh uproariously when we fail to give the proper answer. Apart from the fact that he had this wonderful command of words, and this great facility of writing well-constructed controversial plays, he was not unlike a great many other people whom one knew. I have met Shaws on the board of the Bank of Ireland. I have met Shaw as several Dublin architects, and even as a woman with a Girton accent shooting her mouth off to a captive audience in a Donnybrook bus. They don’t happen to write good plays, but this is a talent rather than an aspect of character.

He could become as muddle-headed as anyone when he succumbed to the fascination of his own villains – a very peculiar characteristic that he had. Major Barbara is packed with anti-Shavian nonsense. Listen carefully to some of the rubbish that comes from the lips of his Caesar and his Captain Brassbound. Consider dispassionately many of his leading women – Candida, Ann Whitefield, Hesione Hushabye, Vivie Warren, and you can realise why he never married – really married. Yet he got away with it – not through Shavianism but thanks to brilliant writing: Joan’s defence of herself, Father Keegan’s description of the Trinity, the love scene in You Never Can Tell, the Frenchman’s speech in Fanny. Of course we laughed and enjoyed him at the time, but let’s face it. On maturer consideration at this distance, Shaw was not unlike lots of us – a well-meaning Rich Man lying about his wealth and terrified at the prospect of becoming a poor man.

For all his Fabian activities and long residence in Hertfordshire, he was peculiarly Irish to the end in insisting that he was hard-up. Living in America for any length of time makes one used to people who pretend that they are better off than they actually are – loving to show off their supposed wealth through big cars and bigger hospitality – and very nice too, if you’re a guest. It always comes as a surprise to me to rediscover that back in Ireland the reverse is largely the case. We have, of course, our financial showoffs, but as a rule the technique is to insist that we have no money at all. This may be due to the presence of a high proportion of spongers in our midst, combined with a traditional fear of being considered mean. But there it is, and Shaw was a good example of it.

He must have been a millionaire several times over at the time of his death, but at that age I believe that he had really convinced himself that he was financially ruined, and that every time he had another revival or sold some more film rights, he would roar that it was costing him more in socialist income tax than he could possibly earn from the deal. His instinct was to be kind in the extreme to people and causes he approved of, but it had to be in secret. It was entirely thanks to him that any English manager would touch my plays; but he never would admit that he had even read them.

I was not one of his closest friends and for a very good reason. You couldn’t sit under that Upas Tree any more than you could sit under the shade of Yeats – if you intended to have any ideas of your own. Like all good children (including Shaw himself) you had to get out into your own little bit of sunlight, and contradict your spiritual parents if your instructions were going to be of any use to you – if you have learnt the lesson of private judgment which they themselves had taught. I don’t even know whether he appreciated the fact. I’d like to think so, but I don’t know because like nearly all really great men, Shaw was as vain as they come, where his own morale was concerned, and like all Dubliners he was particularly sensitive to the malicious scepticism of his own home town, and of other people however raised from the same stable.

It is because I have learnt from Shaw that same scepticism of greatness and a profound dislike of anything that savours of magic that I find it impossible to speak reverentially of him now – not in spite of the fact that he is dead, but because of the fact that he is dead – and if such an attitude requires any justification I can only quote something he once said to me. “Don’t bother,” he said, “about anything they say of you behind your back. The fact that it’s behind your back at least proves that they have a regard for you. It’s only what they say to your face that must be taken seriously.”

Now that remark and the implications behind it illustrate a side of Shaw which is not often talked about but which is quite as important as any of his prefaces.

He is supposed to have been an arch-advocate of the Economic Motive, a millionaire socialist with an eye wide open to the value of money. Maybe he was but what I say is – the more he was, the more fascinating it is to find such a man – like all other great men I have ever met – a prey to the entirely uneconomic sin of Vanity. And by Vanity I don’t mean the thing that schoolchildren are sneering at when they say of one another, “He thinks a lot of himself.” Shaw had every reason to think a lot of himself and if he did it wouldn’t matter. I mean that entirely irrational emotion all mixed up with morale that inspires one man to squander his substance in showing off and another to go to his grave rather than make the best of a mistake.

There was no economic motive behind the writing of his last half-a-dozen plays. Nor did he write them because he had something to say. One of the most significant things about Shaw is the fact that he had really nothing at all to say about any of the fascinating issues that the years after 1939 raised.

Nobody can blame him for this. He was a very old man. The point that I want to make is that he himself would have been furious at this excuse – and that – granting this – he still went on writing plays and what is more he wanted people to tell him that they were good.

One of the most memorable days I spent with Shaw was as early as 1935. It was at Malvern. The conversation of both him and his wife came round again and again to the same subject. It was either Too True to be Good or On the Rocks. I can’t honestly remember which. All I do remember is that I knew what I was supposed to say and it was that this dim work – whichever it was – was his best play. Not Joan or Heartbreak House or Man and Superman but Too True to be Good. And why? Well you can decide that for yourself. But I believe it was because he was not satisfied with what he had already done. He must still write better and better plays even when he had nothing more to say. Perfectly understandable I agree, in any ordinary mortal motivated by pride and all the irrational complexes that follow from pride. And that is just what I want to say that Shaw was.

To another Dubliner one of the most revealing things about Shaw is the fact that only in his old age did he ever reveal what to him appears to have been a terrible secret – the fact that for a short time in his early youth he attended Marlboro Street School and could never bring himself to mention this perfectly respectable fact for seventy years. It’s true that he did mention it in the end but only at the end, and what a block of social and religious pride this reveals in his mind can only really be appreciated by an Irish Protestant. These sorts of things in a man’s background may seem trivial and unimportant but they give clues to the assumptions and the snobismes of the formative years of his life that are far more lasting than anything that happens later on. The rest is veneer and intellectual. His childhood is what we have got to know about – not what he says about himself. And I’m personally quite sure that there are other secrets in his life that he has not revealed at all. This must be clear from the regular pattern of his treatment of biographers.

If you were to tell Shaw that you intended to examine and write about his life, he would at first forbid you to do so. Then if you went on and said you were going to do it whether he helped you or not, he usually went to the other extreme and loaded you down with information about his past. Of course this may just have been natural bonté on his part. It may on the other hand have been the reaction of a man who didn’t want you to dig out the facts for yourself.

What the real facts about his background may be I do not know, and I don’t believe that his definitive biography has been written as yet in this connection. I am sure that there is nothing to his discredit in it, but I am not at all sure that he didn’t think that there was and that he had a quaintly Victorian fear about our finding out.

The fact is that he was a much more interesting person – as a person – than either he or the Shavolaters would have us believe. If he had his way he would have us regard him as a keen and clear-sighted intellect that was always right in what he said both politically and philosophically and who never made a slip-up or did a foolish thing all his life through. And the fact that he has so successfully rammed this view down the throats of the public is at the back of the incredible dullness of nearly everything we know about Shaw’s life. All honour to his plays and his prefaces for which he has been amply rewarded and for which he needs no further praise from me. But really his life and his example, his knickerbockers and his vegetables, his Fabian pamphlets and his delicate fuss over actresses – it’s all so like Ayot St Lawrence, which is about as an undistinguished a villa as is going. And none of it does justice to the Shaw inside – this pastiche of at least six of the seven deadly sins – I think we may probably omit Lust from the list, but none of the others.

His life is a striking example of the peril of success. After a life of contradicting everybody, the world suddenly turned round and agreed with him, and as his advice had always been amusing and stimulating but almost invariably wrong, the world became an intolerable place to live in and he had nobody to blame but himself. No wonder he had nothing further to say.

What a subject for a play by himself! One of the reasons for the extraordinary vigour of some of his arguments was the fact that he was not at all superior to prejudice – prejudice based on purely personal feelings. He was prejudiced for instance about education and about the medical profession. He was prejudiced – I believe – about people like Oscar Wilde – not that he didn’t stand up for Wilde after the disaster. But he used to deprecate Wilde as a writer in spite of – or maybe because of – all he owed to Wilde’s style himself. To the end he could never bring himself to admit that The Importance of Being Earnest was a good play. The man who wrote the Revolutionists’ Handbook and created John Tanner could never bring himself to admit that he owed anything to Wilde. If he owed anything to anybody he would insist that it was to the author of Cool as a Cucumber. It was the prejudice, I suggest, of Synge Street against Merrion Square – to use another Dublinism – and he never got over it. Compare this with his attitude towards O’Casey who was not Merrion Square and was proud of that fact. He always spoke very highly of O’Casey. In fact I remember him once saying that the Second Act of The Silver Tassie – the War Act – was the finest thing that had ever been written for the stage. Well it is a good act, but to describe it with a generalisation of that kind can hardly be a considered judgment. It was an expression of regard based on – should one say – the opposite of prejudice. Shaw in fact was not innocent of emotional judgments. And thank goodness for it, I say. Because the picture he liked to paint of himself as a bright Smartie who always knew the answer and said it just before everybody else is a boring picture – like one of those frightful children who always knows the answers to other people’s riddles and says it with a nasty laugh – and it’s one that he doesn’t deserve.

Nor was he a particularly kind person as is so often said about him. In his old age he used to repudiate most of the rude remarks about other people that have been attributed to him. But here again I don’t think he was doing himself justice. He could be exceedingly unkind particularly to other writers. It is sometimes said how much he helped aspiring authors like T.E. Lawrence. But the fact is, it wasn’t Shaw who took up T.E. Lawrence at all. It was Mrs Shaw.

And if I may venture a private opinion I think that if it hadn’t been for Mrs Shaw – a formidable though very charming old lady who definitely kept him in order – he would have had a great many more enemies than he did have. It is a lamentable thing that she didn’t survive him. It would have saved his latter years from some situations which can hardly be spoken about yet but which I hope have been described permanently for posterity, because they make a fantastic ending to the life of a very great man that is almost as sardonic as the last days of Swift.

I once asked him if he had ever managed to collect any royalties from a certain character who owed some to me as well. Shaw gave a snort of laughter and said, “My dear fellow do you expect to get paid? You’re very well off if he hasn’t borrowed from you.” Next week I did actually get a request for a loan of £20.

A few weeks before the Blitz on London began during the last war, we were once again alone in his London apartment, standing by one of the windows and looking down on an adjacent area cleared of its buildings, where excavations were taking place probably in preparation for the coming holocaust. And it suddenly struck me as odd that in the course of our conversation over lunch no mention whatever had been made – or invited – about the war, its merits or its probable outcome. He had always been most vocal on the subject of the First War even to the extent of incurring some unpopularity. Yet he appeared to have nothing to say about this one, and showed no wish to brood upon the subject. Was this because it seemed that the picture of the Human Race as depicted in the last part of Back to Methuselah was turning out to be so much nonsense? Maybe the future world to which we were heading was not going to be one of permanently superb weather in which our descendants, rejoicing in Greek classical names, would be gambolling around an Embryo emerging, not from a sordid vulva, but from a cleanly egg, and their Elders, with three hundred years of experience to their credit, would look on, while brooding over the charms of pure mathematics. Or had he come to wonder, if Hitler was beaten in the end, whether there was not a distinct possibility that the West might find itself saddled with a Shavian society?

By this I mean a future dedicated to the Shavian objectives of more money for less work for rich and poor alike, for a dictatorship of the unemployed and the encouragement of delinquent youth, for fun in punishment in more enjoyable jails with compulsory bail and prizes for popular pickets, and concordats, universal oneupmanship and possibly mixed rugby football – which as a matter of fact I have since seen.

I find it hard to believe that Shaw looked forward with any degree of pleasure to this sort of triumph over Fascism, although he struggled against it for another ten years and with another bunch of plays. For it might be said that Hitler’s war had killed his taste for magnificent villains in his best parts. There were no more Andrew Undershafts, no Brassbounds or Napoleons, no return of Joan’s Inquisitor, or even of General Burgoyne. Instead he wrote of Edward VIII under a thin disguise, and of Lawrence of Arabia, neither of whom are of the old Shavian calibre, any more than are any of his later women.

Nevertheless he is the personality on whose shoulders most people of my generation, assuming they have any thought processes at all, are sitting. And this applies both as regards our successes and our mistakes. Although dangerous to imitate, he was, until recently, the inspiration of a whole generation of modern dramatists. On the other hand, as a critic of the current scene he seems to have set a disastrous example to all the second-rate journalists of the day.

At the time of his ninetieth birthday in 1946, when all the British and American press was roaring to get interviews and photographs of him, and offering untold sums that would have further ruined his tax situation, he fought them all off with statements that he was far too busy and hated birthdays anyhow – both of which excuses were quite untrue. As Programme Director of BBC Television at the time and as a fellow Dubliner I was one of our easiest contacts with Shaw. So I took on the job, and knowing the peculiarities of the man, I didn’t ask him directly to let us come and see him.

Taking it as an assumption that nobody even knew about his significant age, I wrote him a brief note mentioning the fact that the first play to be presented on the new BBC Radio Third Programme was to be Man and Superman in its entirety, and that we hoped he would enjoy it. I passed on some casual news about Dublin and the Abbey and how odd it was that so many of us Irish were helping to make something out of television – the only service of its kind at the time – and I finished up with some expressions of regret that none of our viewers, most of whom loved his plays, would ever be able to see him in person.

A day or two later, back came one of his postcards. “The thing is not impossible… As I shall have to stage manage it myself you must let me know exactly how long it is to be… I must do some talking; so do not rush your camera men down and take me by surprise. I shall need a day or two to write the play. GBS.” Next week there we were out at Ayot St Lawrence with a camera crew and no interviewers. Just Shaw himself, talking extemporaneously, or so it seemed, for half an hour, out in the sunlight in his garden, with an occasional background of Britain’s new jet planes zooming overhead, much to the discomfiture of the cameraman, who wanted to stop work till the interruption was past. But I wouldn’t let them stop, for it was no interruption, but the sound of the post-war world bidding farewell to Shaw precisely as he was saying the same to us – Good Bye – (waving his hand) Good Bye – Good Bye.

It was in fact Good Bye, and a greater gift to Dublin and to England’s infant television than Shaw ever knew about, because, at the time, the newsreels were doing their best to kill the coming medium as a news service by refusing us any of their films. But as soon as they discovered that we had an exclusive of Shaw on the ninetieth birthday, they had to lift the ban and come to terms, which has been the case ever since. Shaw: undoubtedly a great man who would do anything for his home town and camp followers, provided he wasn’t asked.

Shortly afterwards we read Man and Superman over the air including the stage directions, during that first week of the Third Programme. It took about six hours, and I was pleased to be asked to read the stage directions myself, probably on account of my Dublin accent, which I am told was not unlike Shaw’s. Shaw made no comment, but many years later Colin Wilson did, in the collection of essays edited by Michael Holroyd entitled “The Genius of Shaw”. In 1946 Wilson was a nihilistic alienated 15-year-old. He describes how he came home from the cinema that night in October to switch on the new Third Programme and heard the opening words of Act Three spoken by a narrator: “Evening in the Sierra Nevada. Rolling slopes of brown with olive trees…”

At first I was amused and excited – it was more witty and intelligent than anything I had ever heard on the radio. And then as Don Juan began to speak about the purpose of human existence, I experienced a sensation like cold water being poured down my back. “Life was driving at brains – at its darling object: an organ by which it can attain not only self-consciousness but self-understanding.” It was as if a bubble had burst; [my] deep underlying sense of detachment and futility disappeared; someone else was talking about the problem that I thought incommunicable. When I went to bed after midnight, I felt exhausted and slightly stunned; yet underneath the confusion, there was a deep certainty that my life had changed.

Copyright 1996 by Rory Johnston.