Deep In Echo Park, A Bohemian Nexus

BY LIONEL ROLFE

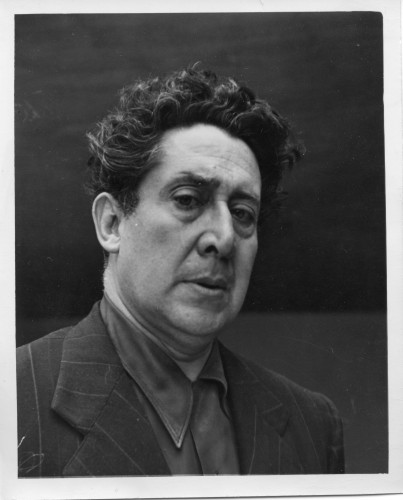

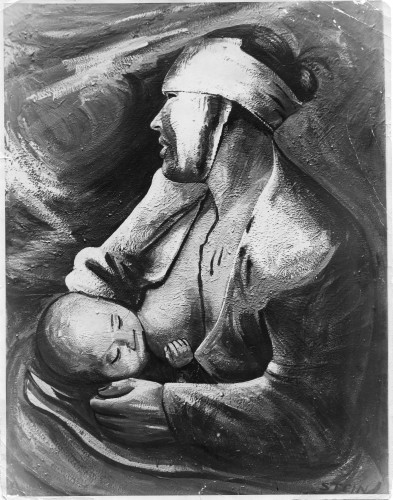

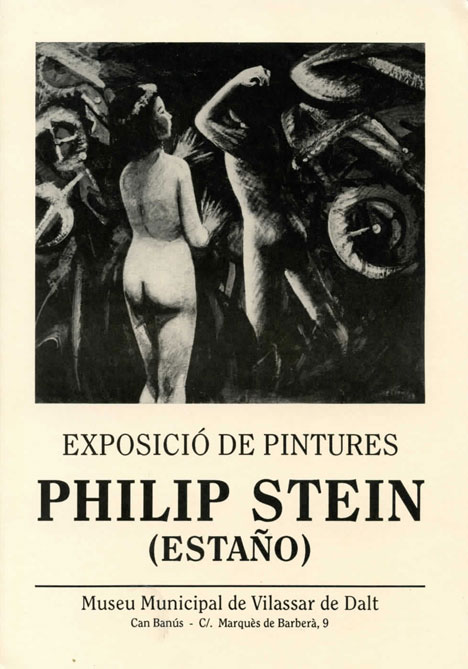

Long time Echo Park residents Anne Stein and Gary Leonard are planning to showcase the paintings of Anne’s father, Philip Stein, at their Take My Picture Gallery in downtown Los Angeles. They are doing so as the restored Siqueiros mural “American Tropical” is about to be unveiled in Olvera Street.

The timing is not just coincidence.

First, Gary Leonard has been a character and photographer around town for many years. He was becoming known as a photographer 20 years ago when he came to the attention of Los Angeles by creating a gigantic “sculpture” over most of the front yard of his house at the top of Echo Park Avenue. He was using such miscellaneous items as garden tools, car parts, household items and even a replica of a World War II bomb in its construction. The sculpture even had an archway to the front door hidden behind it, built with scraps of metal, rusty bedsprings, bicycle chains and dolls.

Leonard was building the sculpture as a kind of act of outrage and therapy at the financial and psychological problems a terrible divorce was putting on him. He had lived in the house at 2446 Echo Park Avenue for more than a decade and now it looked like he was going to loose it.

Some of his neighbors liked their eccentric neighbor’s artwork. One fan put up a spotlight that lit up Leonard’s artwork at night, creating a garish and surrealistic scene. There were some who regarded his artwork as the neighborhood’s Watts Towers. Then other neighbors did not like what he had done at all, and banded together to push him out.

Since then, he has pursued his “Take My Picture” column in several newspapers, first gaining attention in the old Los Angeles Reader, City Beat, the Downtown News and now LA Observed. He has even opened up a gallery in downtown by the same name.

Anne Stein was born in Mexico City in the 1950s because her father had left Los Angeles on the GI bill to study art in San Miguel. He ended up working with the great Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros between 1948 and 1958 on most of his major murals. He then brought his family back to the New York area and except for an eight year sojourn in Spain, spent the rest of his life as an artist and activist in the east.

When Stein died at 90 in 2009, Anne and Gary rented a truck and drove the artwork from New York to Echo Park and then installed the paintings at Take My Picture gallery.

Siqueiros had been commissioned to paint three murals in Los Angeles. “American Tropical” at El Pueblo was whitewashed within a month of its completion in 1932. Mexican revolutionaries, or any revolutionaries, never found Los Angeles a friendly place.

At the beginning of the century, Ricardo Magon, a major architect of the 1921 Mexican Revolution, lived and did his work in Los Angeles. Like Siqueiros, Magon was punished–spending a year in an American prison–the result, primarily, of the enmity of the Los Angeles Times editor and publisher Gen. Otis, who was also a big landlord in Mexico and an avid supporter of the dictator Porfirio Diaz.

Otis ran Los Angeles like his personal fiefdom, and he hated Magon, just as he most surely would have hated Siqueiros.

In the 1980s Stein wrote Siqueiros: His Life and Works, still the major biography of Siqueiros.

Phil had done set design for the New York theaters, studied art at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, then he came to Los Angeles and went to Chouinard. Then as a Columbia studios set designer, he got involved in the great 1946 Hollywood strike, Vallen said. He spent several months in jail in Lincoln Heights for his efforts.

When he and his wife left Los Angeles and moved to Mexico City, Stein was a veteran of the Great Depression as well as World War II, where he had been a meteorologist. After the war, with the help of the GI bill, he pursued a career in the thing he had cared about the most–art.

Mark Vallen, a well-known artist and art historian with his own blog (http://www.art-for-a-change.com/Vallen/vallen.htm), said Stein had a very special relationship with Siqueiros.

“Stein went to work for Siqueiros for 10 years and that relationship grew and deepened. Siqueiros gave him the name Estano. Stein-Estano was at first one of several Siqueiros assistants, but he became the main assistant and got involved with several of his greatest murals in Mexico City during that time,” Vallen said.

Vallen said that Stein became “so closely aligned with Siqueiros” people hardly knew Stein was a significant artist in his own right, heavily influenced by the American jazz scene.

When Stein died in 2009, the New York Times noted his passing with a substantial article about “Phil Stein, Muralist Who Adorned Village Vanguard Club Dies At 90.”

The famed jazz club, which is still going, was run and founded by Stein’s sister, Lorraine Gordon and her husband, Max Gordon. For years, there were three large Stein murals on the club’s triangle of walls, two were removed because of water damage but the mural on the back wall remains. Stein loved hot jazz like Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong, but was less excited by the cool jazz performed at the Vanguard.

“What sustained Stein, and enabled him “to go to hell and back,what sustained his art, was the thought that art could make the world a better place and that was the school of American realism,” Vallen said. For Stein, the great Mexican muralist was the inevitable mentor.

“Unfortunately fame eluded Stein because he was persistent in following realism when the abstract was dominating,” Vallen said, noting that Stein wasn’t going to go any where any way because this was the time of McCarthy, when the United States flirted heavily with fascism. “Maybe things will be different with the passing of time,” Vallen said.

Vallen said his own interest in Siqueiros began when his parents took him downtown and showed him where the mural in Olvera Street was.

This was in the 1950s, and Vallen was six or seven years old. He was fascinated by why it had been whitewashed. “There were enemies coming from all quarters,” he said. “Siqueiros’ politics were very clear,” he said, admitting he was “amazed” that the mural is getting such love and care now when the forces of fascism are once again swirling around.

Luckily, Vallen said, there are “some people who love this mural and understand its historic significance,” adding “I’m sure there are others who will snipe at him.”

Vallen is grateful that the Getty Museum has been a main proponent behind restoring “American Tropical.” They did so despite the fact that “American Tropical” is, after all, a Siqueiros, thus its themes are revolutionary, speaking up unabashedly about the oppression of American Imperialism and Mexican Indians.

Siqueiros was, of course, one of the trio of great Mexican muralists, including Diego Rivera and Jose Orozco. The three of them created the Mexican muralist movement, which had its roots in the most classic of traditions, the Renaissance muralists of Italy.

In preparation for the unveiling of “American Tropical,” the city fathers of Los Angeles declared April 20 “Siqueiros Day” and even though Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa has lost much of his credibility with folks on his political left, he talked glowingly of the great man. He just didn’t use terms like “American Imperialism.” Just as well, Vallen said.

Vallen complimented Mayor Villaraigosa for managing to avoid being overly political when he endorsed efforts to save the mural for posterity.

Anne said that a turning point for her father before Siqueiros came as a 15-year-old teenager growing up poor in New Jersey, Stein used to catch the tail winds of trucks, as he rode his bicycle out to Newark Airport. He loved experimental airplanes and liked to photograph them with his homemade camera. Like a lot of folks who grew up in the Depression, he was good with designing and keeping machines working. Anne said that her father talked about watching Archile Gorky painting a mural on a building at the airport. Archile Gorky was an artist who insisted he was related to Maxim Gorky. He was not. He had been born in Armenia, escaped the Genocide, and ended up in New York where he became a significant artist. He was what would now be called a “social realist,” not part of the “modern art” movement. For Stein, encountering Gorky, triggered a revelation that art could be a higher calling.

Like many others of that age, Stein was a dedicated and talented artist who was also highly political. He had come to the conclusion that he needed Siqueiros because Siqueiros was not just an artist, he was the greatest revolutionary artist of all time. The muralists all owed their inspiration to the Renaissance fresco painters. Think of the Italian renaissance mural painting in the 1500s–think of Michelangelo painting the ceilings and walls of the Sistine Chapel.

For Stein, meeting Siqueiros was a turning point. “It solved the problem of the basis of my art,” he said.

Plainly, Anne said, Siqueiros had had an enormous impact not only on her father but a lot of other people. “His energy, his world view, the boldness of his painting, all became very embedded in people around him.”

The paintings of Philip Stein can be previewed at Take My Picture Gallery at 860 S. Broadway.

*