City Spends $100 Million a Year on Homeless, Mostly with Few Results

Leslie Evans

City Administrative Officer Miguel A. Santana released a 21-page report on L.A. homelessness April 16 to a chorus of criticism. The annual costs were much higher than people expected, conservatively at least $100 million, and precious little of that went to housing or other expenses that got anyone off the streets.

The amount looked like a lot, but in a city budget of $8.57 billion it came to just .017%, mainly showing that the city doesn’t take homelessness seriously and hasn’t made a significant investment in trying to end it.

Santana’s report concluded that the main achievement of the recent period has been the creation of the Coordinated Entry System (CES), which is working to replace the multiple first-come, first-served places where homeless people register for the extremely limited amount of housing, now with a citywide coordinated database that ranks applicants on the basis of need.

Beyond that, while 15 city agencies interact with the homeless, the study found “no consistent process across departments in interactions with homeless individuals, homeless encampments, or other issues related to homelessness, and no systematic efforts to connect the homeless with assessment and case management.”

Basically city agencies telephone or email the grossly under-funded 19 staff members of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s Emergency Response Team (ERT), the police, or, if a homeless person is ill, the Fire Department paramedics. This is where the great majority of the $100 million expense is incurred.

The report said that LAPD “estimated that it spent anywhere from $53.6 million to $87.3 million in one year on interactions with the homeless, not including costs incurred from patrol officers’ time.” Some 14.23% of all LAPD arrests are of transients.

The Fire Department estimated at least 6.6 percent of its ambulance transports were for homeless patients.

Critics of the report demand that the money be spent on housing instead of “criminalizing the homeless.” Large numbers of the homeless are mentally ill, or addicted to drugs or alcohol. This is not something created by the police, but a failure of the government, when long-term institutionalized mental patients were made homeless at the beginning of the 1970s when existing institutions turned them out on the streets, and promised community housing and mental clinics were never provided. Later generations have followed on their heels, where they were joined by long-term structural unemployed, as jobs were outsourced overseas. Many people who lost their housing fell into addiction and alcoholism.

There is a high level of petty crime and violence in this population, both as perpetrators and as victims. $6 million of LAPD’s expenses, for example, go to a mental evaluation team of mental health professionals, and $6.7 million goes to its Safer Cities Initiative in Skid Row, which has as one of its functions protecting the homeless from gang members and drug dealers. Obviously most of the .017% of the city budget now spent to maintain order, to clean camps, to provide what mental health services there are, and the essential ambulance and hospital services cannot be taken away to build housing. And if every penny were removed, prorated over the 23,000 homeless who were on the city streets in 2013 (we don’t yet have the numbers from the 2015 count), it would total $4,348 per person, not enough to house very many people. Plainly a massive additional effort is needed to eradicate homelessness in our city, not some reallocation of the tiny amount now being spent. To have some sense of scale, a single building, the U.S. Bank tower, at 633 W. Fifth Street, back in 1989 cost $350 million to build.

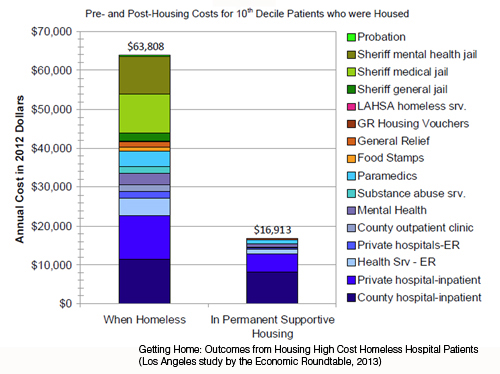

The City Administrative Officer’s report doesn’t include the cost of the homeless on Los Angeles’ health care system. In a 2013 study of homeless patients in Los Angeles hospitals by the Economic Roundtable (Getting Home: Outcomes from Housing High Cost Homeless Hospital Patients) they found that the most chronically ill 10% of homeless patients cost the hospitals an average of $63,808 each when living on the street. When provided housing, this dropped to $16,913.

Miguel Santana’s report says it is in favor of a policy of “housing first,” of not demanding that homeless people go sober or give up drugs to get a place to live. Successful Housing First pilot projects have been carried out in Anchorage, Alaska, Atlanta, Austin, TX, Chicago, Denver, New York, Philadelphia, Portland, Oregon, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, DC.

So far, this seems to be just an aspiration in Los Angeles. There is extremely little money for real housing. The city agencies just mainly call LAHSA’s Emergency Response Team. But only in cases where people have just been dumped on the street and don’t know where to go are these teams likely to have much impact, or where the homeless person has been unable to establish a stable tent or home-made shelter. Usually all an outreach team can promise is a few nights in a crowded and often dangerous city dormitory. This is most effective for priority cases, mainly for families with children or young people or someone sleeping unprotected in an alley.

There is no realistic incentive for a homeless person to abandon a tent or their own carefully constructed shelter, where they have possessions they can’t carry to a city shelter, as in my photo above, taken a few days ago on the 42nd Street bridge over the Harbor Freeway. That man would lose his belongings, only have to move again in a day or two. So, often the phone call gives the feeling that we have done something, but until there is the offer of housing, the feeling is usually illusory. If the offer didn’t include housing it was too little.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.