CHAPTER 11 “TOKEN GESTURES” FROM UMBERTO TOSI’S NOVEL, OUR OWN KIND

(Umberto Tosi, author of Ophelia Rising, was an editor and staff writer for the Los Angeles Times from 1959-1971.)

Roy Wolfe slides onto the barstool next to Benny and lights a Camel. “Gotta quit these things.”

Roy Wolfe slides onto the barstool next to Benny and lights a Camel. “Gotta quit these things.”

“More doctors smoke camels than any other cigarette.” Gordon feeds the line.

“He’d walk a mile for a Camel,” Benny cues off the ad that actually had just flashed on the muted bar TV, and bums one off Roy.

Roy acknowledges Gordon with a sidelong glance, elbows Benny, gives him a fag and lets him light up off of his. “Fraternizing with the enemy again, Benny?” Smoke envelopes them in a blue-gray twilight like doomed doughboys in World War I trenches.

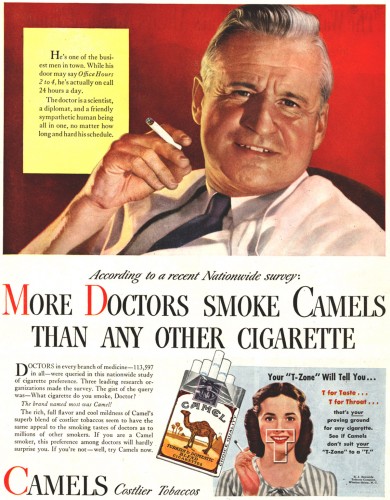

Camel Cigarette ad from the period, with slogan quoted in Nino’s text

Roy reminds Benny of a younger Nat King Cole, with high forehead, sculpted cheekbones and an easy, kind of sexy smile, but a gravelly voice. He doesn’t trust himself to say that to anyone, for fear it will sound like he thinks all black people look alike.

Maybe. Benny is white, after all – a whiter shade of pale. Procol Harum’s pseudo-psychedelic one-trick hit gives Benny a contact high and a case of hives, because he has to grit his teeth and give a shit-eating smile whenever people mention the title as a cool way of letting him know they notice he’s an albino.

“Yeah? Well then, where are my 16 vestal virgins?”

“Leaving for the coast.”

“Yeah. Har har. Then I’m shit out of luck.”

Roy, he knows, feels the same about people telling him he looks like Nat Cole. “I even get asked for my fuckin’ autograph,” he’s confided to Benny a few times. “I can’t even carry a tune… I tell ’em, hey, no, I’m Bo Diddley. Unless it’s a cop who pulls me over, then I shut the fuck up. I get a lot of that.”

“Driving while Bo Diddley. That’s a serious charge,” Benny puffs, stifles a cough and balances his Camel on the ashtray.

Gordon drains off his Scotch. “We were just discussing scifi.”

“Benny knows lots about outer space,” Roy says takes a drag and nods to the bartender to pour him his usual bourbon, rocks. “He’s out there a lot.”

They spar a while like that, glancing at each other’s reflections between whiskey bottles in the big bar mirror. Then all at once, they go quiet into their own thoughts amid the ripples of bar chatter.

“Well, gotta go.” Gordon puts cash down and gives a high sign to the bartender. “See you gentlemen in the papers.” Gordon stands up.

“Watch for my big Howard Hughes exposé,” Roy gives him deadpan, off the mirror.

Howard Hughes from the 1940s

“Been done,” says Gordon, and is out the door.

“Must be hard to breathe, stuffed that far back in the closet.” Roy knows everyone’s secrets, including that Gordon keeps a Tab Hunter look-alike, men’s swimwear model named Stevie up in Silver Lake.

“Well?” Benny raises his eyebrows. “What happened with Sherman?

Last time they talked, Roy had been on his way to a showdown with the city editor over a South Central cops-and-kids story that had been spiked. “Next time you see me, I might be unemployed,” he had told Benny, “maybe even hauled off for aggravated assault on an editor.”

“Yeah, yeah.” Benny had waved him on. “Sherman will back down. Times can’t afford to lose you, especially right now.”

Roy had just spent ten days on the road covering uprisings in major cities after the MLK assassination – reporting from the incendiary hearts of the war zones that America’s urban centers had become since the killing. His dispatches had appeared on the left shoulder of page one, day after day – lucid, lyrical, personal stories that conveyed to safely insulated Los Angelenos what it was like for those at ground zero. He portrayed a family holed up in an attic all night in burning Philadelphia. He took readers along on patrol with a leader of the Blackstone Rangers out to protect black-owned businesses amid the burning and looting of Chicago’s sprawling West Side.

Even the watered down, trimmed versions that ran each day had power, but Benny had read the originals as they had come in on the wire unedited, and was nearly as appalled as the author himself. His editors mouthed glib excuses on Roy’s return – citing space considerations, never race, nor their obvious inclination to censor whatever they found disturbing.

The supreme irony was that the paper that more than any other, defined L.A., kept its best urban reporter as far away from Los Angeles as possible.

Only the managing editor – tall, square-jawed, blunt-spoken, cigar-chomping Frank Harbin, the one everyone called “Lurch,” was candid about the editorial board’s thinking: “We could start another Watts riot running stuff like you write raw.”

That was after Roy had filed a story about a two LAPD officers beating up a black kid they had stopped on his way to a prom and sexually harassing his date in the back seat of a squad car by slipping a loaded gun between her legs. The story was all checked out, multiple sources an all, but the editors killed it.

Roy listened, then responded in a low voice. “It’s not my job to second-guess events, just to tell the truth as I see it, and not protect the police or politicians, not even to keep peace and civil order.”

He kept his cool. But they seemed to send him out of L.A. a lot more often after that run-in. Perhaps it was coincidence. But it kept him from stirring things up in the Times’ backyard for a while.

“You keep ignoring this kind of thing, and you will have another uprising, bigger than the last when black folks have had enough of it,” Roy had prophesied, accurately, but that was not to happen until 1991, and no one who knew the real L.A., as opposed to the TV cop show one, was surprised.

Interior, Redwood Bar & Grill, downtown LA, 2nd St.

Again, Roy zipped it. He had learned how to play this game a long time back, as eager young reporter for the Paris International Herald Tribune, just out of Columbia J-school. He had covered a different war then, in Algeria, and its bloody Pied-Noir terrorist aftermath in France.

The Times had hired Roy right after the Watts Riots of 1964 when the Chandler Family flagship didn’t have but one black reporter and he, an inexperienced hire from the its truck dispatch office. That didn’t signal, as Roy found out, any expansion in the paper’s curiosity about South Central once the uprising ended.

Roy goes over it all once again at the Redwood bar with Benny, letting off steam. “You were right. Sherman caved, but it’s just a ruse. They will start all over again next time I file.”

“Killing you with kindness,” Benny noted.

“… and Wonder Bread. Truth is, I can’t afford to quit. I got kids to support.”

“I know that one,” Benny added. “Except I’m not exactly indispensable.”

Benny fills Roy in on his wild encounter with the Prophet of Spring Street. Roy listens and nods.

In comes Jorge. “Well if it isn’t Pinky and Blue Gum. Mind if I join you losers?”

“Tortilla Fats!.” Roy raises a mock toast to the robust Jorge Ramos and motions for him to sit. Jorge waves to the waitress for his usual Negra Modelo. He grins like he’s reading your mind, and usually is. He smooths strands of gray-speckled straight black hair back from his forehead with chubby hands, a boyish gesture, contradicted by the intensity of his brown, wide-set eyes that move about the room, pinpointing everyone and everything.

The waitress is quick with his beer, which he sips straight from the bottle, setting aside the little lime wedge. “Here we are, los tokens de estrange senora la Reina de Los Angeles Tiempo. Representing America’s oppressed minorities… even you, whiter-than-whitey,” he grins at Benny.

“… by staying drunk and invisible.” Roy waves his glass.

Benny joins the toast but says nothing. He can never get comfortable with that stuff.

Roy coughs, put out his cigarette and sips his bourbon, neat. “Benny here was just telling me about how he saw that crazy sonofabitch street preacher ranting on Bobby Kennedy and waving a gun.”

“Well, it wasn’t that dramatic.” Benny coughs, self-consciously.

Jorge pats Benny’s shoulder. “Que loco, that one. I need ear plugs when he comes down the street. Hey, it could happen. Anything could. Look at what happened to JFK and now, Martin Luther King, and in, hell, every day in Saigon, you know every step could be your last.” Jorge had just returned from six months reporting in Vietnam, before that, the Dominican Republic on the civil war there – anything to keep their best – and only – hawk-eyed Latino reporter from reporting on East L.A.

Roy takes a breath, and cuts in: “You know what comes into your mind at the moment of death?”

Jorge: “How would you know?”

Roy: “Trust me. In Korea, 1951.”

Benny: “Okay. Your girlfriend? Your wife? Kids? The best lay you ever had? If you forgot to pay your light bill?”

“None of the above. It’s surprise! You’re fucking surprised! We know everybody dies, but we always automatically think that meant someone else. You can’t believe it’s you. You say to yourself, ‘fuck, so this is it? I can’t fucking believe this.’”

“Really?”

“Just felt a thud that laid me out, heard nothing – pain came later. Sniper. Bullets travel faster than sound, you kno

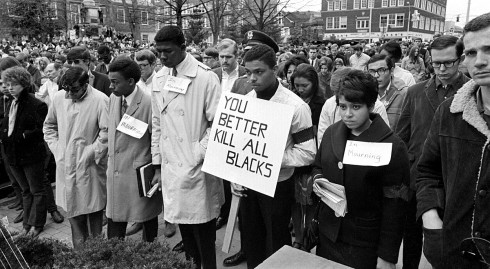

MLK assassination day-of-mourning demonstration, 1968.

You don’t hear the shot.” Roy had been wounded in Korea.

Jorge: “Yeah, but that wasn’t really your last thought, as it turned out. Maybe you were surprised because you knew it wasn’t your time, Roy.”

“It’s never anyone’s time.”

Benny: “You suppose Martin Luther King was surprised when that sniper put out his lights?”

Roy: “He got it in the head. Bullets fly faster than sound. He wouldn’t have heard it coming.”

Jorge: “But he knew what was coming… What he said to the garbage workers there in Memphis, the night before he got it. ‘I been to the mountain’…” Makes your blood run cold.

Benny: “Why does it have to be this way?”

Roy shakes his head and draws on another Camel. “The night desk guy, you know …”

Jorge: “Stumpy Charlie, the one-armed copy bandit.”

Roy: “Yeah, Him. He stands over my desk. I’m pounding out copy for deadline. I look up. He puts his good hand over his heart and says, ‘Roy? My condolences on the death of Martin Luther King.’ I tell him: ‘Okay – and I’ll be sure to convey that to Wasatch for you too.’”

Benny laughs uncomfortably. “Well, he was trying, I guess.”

Roy: “Yeah. Cold. I admit it. But he doesn’t get it. It ain’t my loss. It’s everybody’s fucking loss, and he doesn’t need to apologize for the white race, not to me, anyway. I don’t give two bits for his guilt. I refuse to be Token Man, pretend-integrating the Times to make anybody feel better. And I don’t want to go to fucking Africa either, or live in any black power nation. This is my fucking country as much as yours, warts and all. I just want a nice house, my kid in a nice school. Black folks aren’t the problem, the bigots are and I can’t fix them. They need to fix themselves.”

Jorge applauds. “Nice speech. You should run for President.”

Roy grunts a chuckle. “Don’t make me laugh.”

Benny starts to get up. “Well, guys. It’s been a bit of heaven.”

Roy nods. “Hey, I’ll dig around about Preacher Man. Okay? I want to do something on Bobby anyway, if I can get the okay.”

“Cool. Thanks.” Benny heads off. It’s his last full week with the kids before the court decision is due. And who knows after that?

####

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.