California Road Scholar: More Stories Of The Golden State

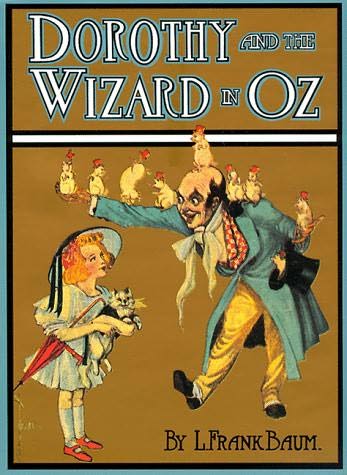

The cover of "Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz." In this -- volume 4 of the Oz series -- Dorothy starts out in California.

By PHYL VAN AMMERS

Joan Didion wrote, in The White Album (1979):

“Kilimanjaro belongs to Ernest Hemingway. Oxford, Mississippi, belongs to William Faulkner… a great deal of Honolulu has always belonged for me to James Jones… A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.”

Didion shaped the way we see California. She descended from pioneers in northern California and often writes with great and clear love but the enduring image I have of her writing is of the protagonist in Play It as It Lays (1970) driving endlessly and compulsively on the roads and freeways of Southern California, wandering through motels and bars, drinking and having sex with second rate actors.

John Steinbeck also shaped the way everyone looks at California. He loved it so radically that he remade it. In his Travels with Charley (1962), Steinbeck crosses the country with his poodle Charley as his companion. He goes through Monterey County and finds a great deal has changed since his childhood but concludes, “I printed once more on my eyes, south, west, and north, and then we hurried away from the permanent and changeless past where my mother is always shooting a wildcat and my father is always burning his name with his love.”

California’s permanent and changeless written travel past begins with the de Portola expedition through California.

Father Juan Crespi was the diarist on the expedition led by Captain Gaspar de Portola (1769) along with a group of 67 men.

Entering the area to become San Diego, Fray Crespi wrote:

“During this march, a good-sized throng of heathens along the way shouted at us a great deal in a loud chorus; all naked, heavily armed, and with large quivers on their backs and bows and arrows in their hands, and all went running along the crests of the hills in view alongside of us…. Our commander charged everyone that no one should shout back to them, as we did not understand what they might be saying to us; instead, the commander himself repeatedly made signs to them to come to the camp without fear, showing them beads and ribbons that he would present to them, but they would never pay attention to anything. They kept us waiting this way the entire day until close to sunset, when they all together gave a loud whoop and vanished from sight and were seen no more that night.”

They entered what is now Los Angeles through Elysian Park. Fr. Crespi wrote:

“After traveling about a league and a half through a pass between low hills we entered a very spacious valley, well grown with cottonwoods and alders, among which ran a beautiful river from north north-west and then doubling the point of a steep hill, it went on afterward to the south.” They also found oil bubbling out of the ground at what would become the La Brea Tar Pits.

At the location of what would one day be San Francisco, Fr. Font wrote:

“On leaving we ascended a small hill and then entered upon a mesa that was very green and flower- covered, with an abundance of wild violets. The mesa is very open, of considerable extent, and level, sloping a little toward the harbor. It must be about half a league wide and somewhat longer, getting narrower until it ends right at the white cliff. This mesa affords a most delightful view, for from it one sees a large part of the port and its islands, as far as the other side, the mouth of the harbor, and of the sea all that the sight can take in as far as beyond the farallones. Indeed, although in my travels I saw very good sites and beautiful country, I saw none which pleased me so much as this. And I think that if it could be well settled like Europe there would not be anything more beautiful in all the world, for it has the best advantages for founding in it a most beautiful city, with all the conveniences desired, by land as well as by sea, with that harbor so remark- able and so spacious, in which may be established shipyards, docks, and anything that might be wished.”

Sarah Royce (1819-1891) is probably best remembered, if she is remembered anymore, as the mother of California philosopher Josiah Royce, who got his bachelor’s degree from UC Berkeley in 1875. Royce Hall, on Royce Drive on the UCLA campus, is named after him. Royce Hall often shows up in movies and television shows as background. Frontier Lady: Recollections of the Gold Rush and Early California (published after her death in 1932), which are Sarah Royce’s diaries, show what it was like for women to set out for the “Golden Gate” from the eastern part of the United States.

She describes crossing the Missouri River:

“(O)n Friday the 8th of June we ventured ourselves and our little all, on board a very uncertain looking ferryboat and were slowly conveyed across the turbid and unfriendly-looking Missouri. The cattle were ‘swum’ across the stream; the men driving them in and frightening them off from the shore in various ways, until a few of the leaders reached the flats on the opposite side. As soon as they were seen to come out of the water there, the others easily followed. A few of the many thus crossed were driven by the strong current beyond the flats and lost, but most of them crossed safely. ….Not very far from the river we began to see the few scattering buildings of Trader’s Point, the Indian Agency for this part of Nebraska Territory.” (This point becomes Omaha City.)

Cholera first spread to the Americas about 1817. Because physicians sometimes treated it with arsenic in the United States, historians do not know how many of the Cholera victims actually died of poisoning.

The oldest of the men who joined Sarah’s wagon train complained of intense pain and sickness. A doctor diagnosed him with Cholera, gave him medicine, and the man died. Sarah wrote:

“….(A) storm began in the evening. The wind moaned fitfully, and rain fell constantly. I could not sleep. I rose and walked softly to the tent door, put the curtains aside and looked out. The body of the dead man lay stretched upon a rudely constructed bier beside our wagon a few rods off, the sheet that was stretched over it flapped in the wind with a sound that suggested the idea of some vindictive creature struggling restlessly in bonds; white its white flutterings, dimly seen, confirmed the ghastly fance. Not many yards beyond, a part of Indians – who had, for a day or two, been playing the part of friendly hangers-on to one of the large companies – had raised a rude skin tent, and built a fire, round which they were seated on the ground—looking unearthly in its flickering light, and chanting, hour after hour, a wild melancholy chant, varied by occasional high, shrill notes as of distressful appeal. The minor key ran through it all. I knew it was a death dirge.”

A typescript of Helen McCowen Carpenter’s (1856) diary of her pioneer travels to Potter Valley, near Ukiah, California is at the Henry E. Huntington Library. “A Trip Across the Plains in an Oxcart, 1857.” She became Mendocino County’s first American school teacher, became involved in civil life in the new little city, and helped her husband A.O. Carpenter take photographs of pioneer day Mendocino County. (See Aurelius O. Carpenter: Photographer of the Mendocino Frontier, published by the Grace Hudson Museum in 2006. Grace Hudson, “the Painter Lady,” was one of Helen’s children.)

William Henry Brewer (1828-1910) was an American botanist. He attended Yale in 1848 and studied soil chemistry. In 1855, he studied natural science at the University of Heidelberg, Munich to study organic chemistry, and then to Paris to study chemistry.

Shortly after Brewer’s wife and newborn son died, Josiah D. Whitney (1819-1896. Mount Whitney, the highest point in the continental United States, is named after him. ) invited Brewer to become the chief botanist of the California Geological Survey. He led field parties in the extensive survey of the geology of California. Mount Brewer in the Sierra Nevada mountain range and the rare spruce Picea breweriana are named after him.

Book 1 of Brewer’s Up and Down California comprises the years1860 to 1861. Chapter 2 is “Los Angeles and environs.”Chapter 3 is “More of Southern California.” Chapter 4 is “Starting northward. Chapter 5 “”Santa Barbara.” Chapter 6. “The Coast Road.” Chapter 7 is Salinas Valley and Monterey.

In Chapter 2, he sails from San Francisco on a steamer to San Pedro. He writes, “There are two small rocky islands just at the Golden Gate and they were completely covered with sea lions, a kind of large seal, apparently nearly as large as a walrus. They barked at us as we passed and many tumbled into the sea, but hundreds were basking in the sun or moving about with awkward motions.”

They stop the next day at San Luis Obispo and spend several hours collecting plants, all strange to him. (This sounds like what is today Pebble Beach.)

The arrive in San Pedro, “about 25 miles from here.” The journal does not exactly address where “here” is, but from the context, it is where he first camped for a time to study plants and geology.

They take a small steamer for six miles up the Los Angeles River. I find the idea of taking a small steamer for six miles up the Los Angeles River a little unsettling but this was in December, perhaps it had rained a lot, and perhaps before the river was channelized, it flowed more fully down towards Long Beach.

Looking at Google maps, it appears that six miles from the city of San Pedro up the Los Angeles River as it is today would have brought him to what is now East Compton. They have to wait until the next day for the remainder of their exploration party and set off to the “camp.” It takes about a day to reach the camp.

The camp is on a hill “near the town, perhaps a mile distant, a pretty place.”

He writes from his hill:

“Los Angeles is a city of some 3,500 or 4,000 inhabitants (Per the Los Angeles Almanac, the population in 1860 was 4,385.), nearly a century old, a regular old Spanish-Mexican town, built by the old padres, Catholic-Spanish missionaries, before the American independence. The houses are but one story, mostly built of adobe or sun-burnt brick, with very thick walls and flat roofs. They are so low because of earthquakes, and the style is Mexican. The inhabitants are a mixture of old Spanish, Indian, American and German Jews; the last two have come in lately….The only thing they appear to excel in is riding, and certainly have not seen such riders.”

“….As we stand on a hill over the town, which lies at our feet, one of the loveliest views I ever saw is spread out. Over the level plain to the southwest lies the Pacific, blue in the distance; to the north are the mountains of the Sierra Santa Monica; to the south, beneath us, lies the picturesque town with its flat roofs, the fertile plain and vineyards stretching away to a great distance, to the east, in the distance, are some mountains without name, their sides abrupt and broken (the San Gabriel mountains), while still above them stand the snow covered peaks of San Bernardino. The effect of the pepper, fig, olive, and palm trees in the foreground, with the snow in the distance, is very unusual.”

Brewer states the camp is on a great plain from the Pacific to the mountains. (I assume he means the hill is on the great plain), at a point located about twenty miles from the sea and fifteen miles from the (unnamed but these are the San Gabriel) mountains. The Santa Monica Mountain Range (including what is now Griffith Park) stands to the north of their camp.

In 1860, the town’s northern border bumped up against the Elysian Park hills, Ft. Moore hill, and Bunker Hill. Prudent Beaudry developed Bunker Hill in 1867. Jacob Philippi built the town’s first brewery and roadhouse on top of Ft. Moore hill in 1887. Los Angeles residents walked up the hill and rolled down drunk

Developers and the City have lowered Ft. Moore and Bunker Hill, but, Bunker Hill was the higher.

It looks to me like the explorers camped in the then-wilderness of Bunker Hill, which is now the site of the multi-story oligarchic office buildings that have become the iconic image of Los Angeles.

Ina Coolbrith was a fifteen year old girl living in Los Angeles when Brewer passed through it. She had her first poem published that year in the Star. She left Los Angeles for San Francisco a few years later.

Close to her death in 1925, she wrote: “Retrospect.”

“A breath of balm—of orange bloom!

By what strange fancy wafted me,

Through the lone starlight of the room?

And suddenly I seem to see

“The long, low vale, with tawny edge

Of hills, within the sunset glow;

Cool vine-rows through the cactus hedge,

And fluttering gleams of orchard snow.

“Far off, the slender line of white

Against the blue of ocean’s crest;

The slow sun sinking into night,

A quivering opal in the west.

“Somewhere a stream sings, far away;

Somewhere from out the hidden groves,

And dreamy as the dying day,

Comes the soft coo of mourning doves.

“One moment all the world is peace!

The years like clouds are rolled away,

And I am on those sunny leas,

A child, amid the flowers at play.”

From Yone Noguchi ((1875-1947), about his 1893 travels in California:

“I left San Jose in the early morning for Los Gatos, being given a chance to ride on a wagon by a kindly old farmer. As it was the latter part of April, both sides of the country road were perfectly covered by the cherry-blossoms in full glory. The morning freshness mingled with the fragrance of the flowers; as I was high up in the wagon, I was looking down the flat valley, and this unexpected flower-viewing….called my longing at once to sign in my mind.”

Dorothy Gale (Gage was Baum’s wife’s maiden name. Dorothy Gage was her niece. The real Dorothy only lived five months.) takes a train to stay with Aunt Em’s brother in Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz (1908) Her cousin Zeb picks her up in a buggy. There’s an earthquake, and the children and the horse – who begins to talk – fall through a crevice in the earth.

“The train from ‘Frisco was very late. It should have arrived at Hugson’s Siding at midnight, but it was already five o’clock and the gray dawn was breaking in the east when the little train slowly rumbled up to the open shed that served for the station-house. As it came to a stop the conductor called out in a loud voice:

‘Hugson’s Siding!’

“At once a little girl rose from her seat and walked to the door of the car, carrying a wicker suit-case in one hand and a round bird-cage covered up with newspapers in the other, while a parasol was tucked under her arm. The conductor helped her off the car and then the engineer started his train again, so that it puffed and groaned and moved slowly away up the track. The reason he was so late was because all through the night there were times when the solid earth shook and trembled under him, and the engineer was afraid that at any moment the rails might spread apart and an accident happen to his passengers. So he moved the cars slowly and with caution.”

“The houses of the city were all made of glass, so clear and transparent that one could look through the walls as easily as through a window. Dorothy saw, underneath the roof on which she stood, several rooms used for rest chambers, and even thought she could make out a number of queer forms huddled into the corners of these rooms.

“The roof beside them had a great hole smashed through it, and pieces of glass were lying scattered in every direction. A nearby steeple had been broken off short and the fragments lay heaped beside it. Other buildings were cracked in places or had corners chipped off from them; but they must have been very beautiful before these accidents had happened to mar their perfection. The rainbow tints from the colored suns fell upon the glass city softly and gave to the buildings many delicate, shifting hues which were very pretty to see.

“But not a sound had broken the stillness since the strangers had arrived, except that of their own voices. They began to wonder if there were no people to inhabit this magnificent city of the inner world…”

There was no Hugson’s Siding. There was no Hudson Ranch.

In Jack London’s Valley of the Moon (1913), one of London’s surrogates in the book – “Billy”– and one of his wife Charmian’s surrogates – “Saxon,” travel from Oakland. Billy is an outspoken racist. Key is heroine’s name. Saxon says, “We‘re Saxons, you an‘ me,…and all the Americans that are real Americans, you know, and not Dagoes and Japs and such.”

Jack London alarmed members of his socialist party by declaring, “What the Devil! I am first of all a white man and only then a Socialist!” And he wrote a friend, “Socialism is not an ideal system devised for the happiness of all men. It is devised so as to give more strength to [Northern European] races so that they may survive and inherit the earth to the extinction of the lesser, weaker races.”

White Californians were racist at the time but it’s never completely clear that London, at least in Valley of the Moon, was himself a racist. He also writes about Saxon’s and Billy’s trip on foot:

“It was a good afternoon’s tramp to Niles, passing through the town of Haywards; yet Saxon and Billy found time to diverge from the main county road and take the parallel roads through acres of intense cultivation where the land was farmed to the wheel-tracks. Saxon looked with amazement at these small, brown-skinned immigrants who came to the soil with nothing and yet made the soil pay for itself to the tune of two hundred, of five hundred, and of a thousand dollars an acre.

“On every hand was activity. Women and children were in the fields as well as men. The land was turned endlessly over and over. They seemed never to let it rest. And it rewarded them. It must reward them, or their children would not be able to go to school, nor would so many of them be able to drive by in rattletrap, second-hand buggies or in stout light wagons.

“’Look at their faces,’” Saxon said. “’They are happy and contented. They haven’t faces like the people in our neighborhood after the strikes began.’”

“’Oh, sure, they got a good thing,” Billy agreed. “You can see it stickin’ out all over them. But they needn’t get chesty with me, I can tell you that much just because they’ve jiggerooed us out of our land an’ everything.

“’But they’re not showing any signs of chestiness,” Saxon demurred.

“’No, they’re not, come to think of it. All the same, they ain’t so wise. I bet I could tell ’em a few about horses.’”

Charmian London’s hagiography of her husband’s life (The Book of Jack London by Charmian London, 1922) contains a more interesting tale about their horseback trip through Northern California after the 1906 earthquake. She called that trip “Jack London’s Magic Trail.”

The magic trail was more truthfully Charmian’s trail, one of the routes that she took with her aunt Netta – who was to become an editor of the Overland Monthly, where Netta was to introduce her to the new writer Jack London while he was still married to his first wife Bessie – when Netta was an itinerant travel writer.

Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife Fanny Osborne sailed from San Francisco to the South Seas, where they stayed until Stevenson’s death. The Londons wished to recreate their trip and commissioned a boat to be built at Hunter’s Point in San Francisco. Only the keel had been built before the 1906 earthquake, so the Londons had to postpone their sailing trip.

“A few minutes before five, on the morning of the 18th, upstairs at Wake Robin (the house that the Londons gave to Netta, her husband Roscoe Eames and lover the Reverend Edward Payne next to his “Beauty Ranch” in Glen Ellen) my eyes flew open inexplicably, and I wondered what had stirred me so early. I curled down for a morning nap, when suddenly the earth began to heave, with a sickening onrush of motion for an eternity of seconds. An abrupt pause, and then it seemed as if some great force laid hold of the globe and shook it like a Gargantuan rat. It was the longest half-minute I ever lived through; I lay quite still, watching the tree-tops thrash crazily, as if all the winds of all quarters were at loggerheads.”

Charmian and Jack got on their horses and rode up the side of Mount Sonoma and stopped to watch dust rising from the Napa State Hospital for the Infirm.

“Why, Mate Woman, ” Jack cried, his eyes big with surmise, “I shouldn’t wonder if San Francisco had sunk. That was some earthquake. We don’t know but the Atlantic may be washing up at the feet of the Rocky Mountains!” Charmian wrote that when they reached the top of the mountain, they saw smoke rising from both San Francisco and from Santa Rosa. Most of the buildings in San Francisco did not collapse in the earthquake: they burned when gas lines burst. Santa Rosa’s buildings collapsed, and the city burned.

Hatless, with toilet accessories and reading matter stowed in saddlebags behind Australian saddles, they set out northerly to see what the quake had wreaked upon rural California. At this and that resort, they felt the lighter tremblers that followed the big shake, marking the subsidence of the “Fault” that is supposed to enter from the seabed at Fort Bragg, and zigzag southeasterly across the state.

“From Glen Ellen, to Rincon Valley road, through Petrified Forest to Calistoga to Napa Valley. Calistoga to The Geysers. Thence to Lakeport, on Clear Lake, a by way of Highland Springs. We sailed on Clear Lake.

“Lakeport to Ukiah, via Laurel Dell, Blue Lakes. Ukiah to Willits. Through grandeurs of mountains and redwood forest to logging camp, `Alpine.’ Thence to Fort Bragg, on the coast.

“From Fort Bragg, down the coast, sleeping at lumber villages. Navarro, Albion, Greenwood. Thence to Booneville with luncheon at Philo. Philo to Cloverdale, thence to Brooke Sanitorium. Thence to Santa Rosa, and on down to Glen Ellen.”

The Altrurians of northern Santa Rosa built Brooke Sanitorium. Edward Payne, then a Unitarian minister from Berkeley who embraced Christian Socialism – a movement that stressed the importance of saving society before saving the individual, sought to foster brotherhood among all classes and stressed gradual change, interdependence and mutual obligation among men. Altruria was meant to demonstrate that men would work together willingly for a common good, and that this could be accomplished without violent revolution. (See, unpublished thesis submitted to the Sonoma State University, Shadows on the Land: Sonoma County’s Nineteenth Century Utopian Colonies, by Varene Anderson (1992)

There was, in 1987 when I followed the Magic Trail insofar as it was possible because roads had changed since 1906, a Rincon Valley Road, and no such road shows on the old maps kept in the Santa Rosa library collection. There is an area called Rincon Valley, and there was once a Rincon Valley school.

Charmian’s diary for those days kept in the Jack London collection in The Huntington Library reports that, on May 3, 1906, they rode 30 miles to Calistoga. I figure the Londons rode over what is now called Calistoga Road into Calistoga, and then to Healdsburg. The Calistoga Road begins on Highway 12, and it passes the Petrified Forest, which Robert Louis Stevenson had also visited when he and Fanny honeymooned in an old miner’s lodge in 1880. The lodge is now part of Robert Louis Stevenson State Park on Saint Helena Highway.

Stevenson wrote: “A rough smack of resin was in the air, and a crystal mountain purity. It came pouring over these green slopes by the oceanful. The woods sang aloud, and gave largely of their healthful breath. Gladness seemed to inhabit these upper zones, and we had left indifference behind us in the valley … There are days in a life when thus to climb out of the lowlands seems like scaling heaven.” (Works of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1901)

On May 4, 1906, Jack and Charmian rode up from Healdsburg to The Geysers at the top of the Mayacamas range, where they experienced an aftershock.

In the nineteenth century, stagecoach drivers drove tourists up the precipitous road to a hotel at the top. The hotel and resort are gone, and the geysers are now part of a PG&E plant.

According to a travel article in the August 31, 1869 Boston Journal, the trip was “perilous” and the driver “General Foss” took the road descending from the summit with break neck speed.

East of the Geyser Peak range is a canyon more than a thousand feet deep. A sharp transverse ridge, just wide enough on its narrow crest to afford a carriage road, bridged the chasm. The Boston Journal writer observed:

“Trees fly past like the wind; bushes dash angrily against the wheels; the passengers hold on as if for dear life; the ladies shut their eyes and grasp the arm of some male passenger; and speed down the declivity with lightning rapidity, the horses on a life jump, and General Foss, whip in hand, cracking it about their heads to urge them on. At every lurch of the coach one feels an instinctive dread of being tossed high in air and landed far below in a gorge, or, perchance, spitted upon the top of a sharp pine.”

In Silverado Squatters (1888), Stevenson wrote: “Along the unfenced abominable mountain roads, he (Foss) launches his team with small regard for human life or the doctrine of probabilities. Flinching travelers, who behold themselves coasting eternity at every corner, look with natural admiration at the driver’s huge, impassive, fleshy countenance.”

In Valley of the Moon, the protagonists reach Healdsburg, where Billy hires on as a coach driver.

“Each day the train disgorged passengers for the geysers, and Billy, as if accustomed to it all his life, took the reins of six horses and drove a full load over the mountains in stage time. The second trip he had Saxon beside him on the high box-seat.”

People traveled in the 1930s, most of them looking for work. In 1931, Carlos Bulosan (1913-1956), born in Luzon, the Philippines, he worked in West Coast restaurants and fields at the height of the Depression and became a labor organizer and a radical intellectual. In America Is in the Heart (1946) he wrote:

“I began to be afraid, riding alone in the freight train. I wanted suddenly to go back to Stockton and look for a job in the tomato fields, but the train was already traveling fast. I was in flight again, away from an unknown terror that seemed to follow me everywhere. Dark flight into another place, toward other enemies. But there was a clear sky and the night was alive with stars. I could still see the faint blaze of Stockton’s lights in the distance, a halo arching above it and fading into a blackdrop of darkness.

“In the early morning the train stopped a few miles from Niles, in the midst of a wide grape field. The grapes had been harvested and the bare vines were falling to the ground. The apricot trees were leafless. Three railroad detectives jumped out of a car and ran toward the boxcars. I ran to the vineyard and hid behind a smudge pot, waiting for the next train from Stockton. A few bunches of grapes still hung on the vines, so I filled my pockets and ran for the tracks when the train came….”

In John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath the Joad family leave ecological disaster in their home state during the Great Depression and travel through California looking for work, sometimes finding it, but the work and living conditions are terrible. The influx of “Okies” – meaning poor immigrants from Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, sometimes and Kansas — depressed the price of labor. The name became a term of derision that lasted a long time, even though World War II led to many higher paying jobs under better conditions. The City of Salinas burned Steinbeck’s novels, although now there’s a statue of him in front of the public library and many businesses have the word “Steinbeck” in their names.

Songs that emerged from the migration include Doye O’Dell’s Okies in California (1949), “Oakie Boggie” – the first rock n’roll song — by Jack Guthrie and His Oklahomans, Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee,”(1969), and Woodie Guthrie’s “Dust Bowl Ballads (1940), which included “Talkin’ Dust Bowl Blues,” “Tom Joad,” and “I Ain’t Got No Home in This World Anymore.”

Woodie Guthrie wrote, “Do Re Mi” about the Dust Bowl immigrants:

“Lots of folks back East, they say, is leavin’ home every day,

Beatin’ the hot old dusty way to the California line.

‘Cross the desert sands they roll, gettin’ out of that old dust bowl,

They think they’re goin’ to a sugar bowl, but here’s what they find

Now, the police at the port of entry say,

“You’re number fourteen thousand for today.”

“Oh, if you ain’t got the do re mi, folks, you ain’t got the do re mi,

Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee.

California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see;

But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot

If you ain’t got the do re mi.

“You want to buy you a home or a farm, that can’t deal nobody harm,

Or take your vacation by the mountains or sea.

Don’t swap your old cow for a car, you better stay right where you are,

Better take this little tip from me.

‘Cause I look through the want ads every day

But the headlines on the papers always say:

“If you ain’t got the do re mi, boys, you ain’t got the do re mi,

Why, you better go back to beautiful Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Georgia, Tennessee.

California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see;

But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot

If you ain’t got the do re mi.”

Dorothea Lange – funded by the Resettlement Administration — documented the Dust Bowl migrants in the 1930s. Her iconic photograph of a mother and her children, as “Migrant Mother” is public domain. The subject of her photograph was Florence Owens Thompson, who was picking beets with her children in Nipomo and traveling with them in an old Hudson.

Marxist writer Meridel Le Sueur (1990-1906)- wrote my favorite 1930s travel short story, “The Girl.”

The girl takes the inland wrote and goes through the Tehachapi Mountains. She reads up on the history of the mountains and lists all the Indian tribes and marks the route of the Friars to get to San Francisco where a teaching job waits her.

“She drove slowly through the hot yellow swells, around the firm curves; and the yellow light shone far off in the tawny valleys, where black mares, delicate haunched, grazed, flesh shining as the sun struck off them. The sun beat down like a golden body about to take form on the road ahead of her. She drove very slowly, and something began to loosen in her, and her eyes seemed to dilate and darken as she looked into the fold upon fold of earth flesh lying clear to the horizon….”

She picks up a young hitchhiker.

“They fell down the valley, yellow as a dream. The hills lifted themselves out on the edge of the light. The great animal flesh jointed mountains wrought a craving in her. There was not a tree, not a growth, just the bare swelling rondures of the mountains, the yellow hot swells, as if they were lifting and being driven through an ossified torrent.”

Jack Kerouac, On the Road (Viking Press 1957)

“…Madera, all the rest. Soon it got dusk, a grapy dusk, a purple dusk over tangerine groves and long melon fields; the sun the color of pressed grapes, slashed with burgundy red, the fields the color of love and Spanish mysteries. I stuck my head out the window and took deep breaths of the fragrant air. It was the most beautiful of all moments.”

“He drove me into buzzing Fresno and let me off by the south side of town. I went for a quick Coke in a little grocery by the tracks, and here came a melancholy Armenian youth along the red boxcars, and just at that moment a locomotive howled, and I said to myself, Yes, yes Saroyan’s town.”

“We got off the bus at Main Street, which was no different from where you get off a bus in Kansas City or Chicago or Boston — red brick, dirty, characters drifting by, trolleys grating in the hopeless dawn, the whorey smell of a city….

“South Main Street, where Terry and I took strolls with hot dogs, was a fantastic carnival of lights and wildness. Booted cops frisked people on practically every corner. The beatest characters of the country swarmed on the sidewalks — all of it under those soft Southern California stars that are lost in the brown halo of the huge desert encampment LA really is. You could smell tea, weed, I mean marijuana, floating in the air, together with the chili beans and beer. That grand wild sound of bop floated from beer parlors; it mixed medleys with every kind of cowboy and boogie-woogie in the American night. Everybody looked like Hassel. Wild Negroes with bop caps and goatees came laughing by; then long-haired broken down hipsters straight off Route 66 from New York; then old desert rats, carrying packs and heading for a park bench at the Plaza; then Methodist ministers with raveled sleeves, and an occasional Nature Boy saint in beard and sandals. ….”

Read:

The National Park Service provides an on-line trail guide to the Juan Bautista de Anza (1775- 1776) exploration of California. http://www.solideas.com/DeAnza/TrailGuide/. The full text of de Anza’s California expeditions is available through the Bancroft Library, the Library of the University of California. http://archive.org/stream/anzascaliforniae04bolt/anzascaliforniae04bolt_djvu.txt.

Valley of the Moon is available free on-line at http://www.readcentral.com/book/Jack-London/Read-The-Valley-of-the-Moon-Online.

Charmian London’s book is free online at

http://archive.org/details/bookofjack02londrich.

Pearsall and Erickson, The Californians: Writings of Their Past and Present, Volume II (San Francisco, Hesperian House 1961).

L. Frank Baum, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz, online at http://www.online-literature.com/baum/dorothy-and-the-wizard-in-oz

Brewer’s Up And Down California wasn’t published until after his death. The complete text is available for free on-line. (http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/up_and_down_california/)

Crespí, Juan: A Description of Distant Roads: Original Journals of the First Expedition into California, 1796-1770, edited and translated by Alan K. Brown, San Diego State University Press, 2001, ISBN 1-879691-64-7

Visit:

L. Frank Baum’s house Ozcot was at 1749 N. Cherokee in the Hollywood

District of Los Angeles. The site is occupied now by a bland apartment building.

Carmel Mission Cemetery, Carmel-by-the-Sea, where Fr. Crespi is buried.

Jack London State Park in Glen Ellen, California.

North Beach is next to Chinatown. On 1066 Broadway up a bit from Chinatown is the house where Victorian poet Ina Coolbrith lived in her later years. She died in a friend’s house in Berkeley in 1928. Road Scholars should visit the poet Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore. Ferlinghetti is 94, and the story I heard is that whenever he goes to North Beach he eats free at the restaurants nearby. Allen Ginsburg wrote, “Howl” at 1010 Montgomery. Kerouac lived at 29 Russell Street.

In the alley behind the bookstore is a round metal plaque set in the ground with a little Kerouac writing. Down the street is the Beat Museum, which shows a film about Kerouac, including a walking tour he took in the Sierras with the Beat nature poet Gary Snyder, who still lives in Grass Valley. Ferlinghetti talks in the film about Kerouac’s descent into alcoholism. The Mercury used in one of the films of On the Road is in the museum. Barbra

Streisand’s news photo is in the museum. The article reports, “I was happier as a Beatnik.”

The National Steinbeck Center in Salinas is within walking distance of the Amtrak station. http://www.steinbeck.org/. The depot, constructed in 1942 by the Southern Pacific Railroad, exhibits a pared down Spanish Revival style as influenced by the then-popular Art Deco movement. Spanish Revival elements include the red tile roof and stuccoed walls, while the Art Deco influence is visible in the rectilinear composition and clean lines.

There should be a portal in downtown Los Angeles and a portal in downtown San Francisco. Like the space travelers in the old Star Trek television series, someone fiddles with big dials and beams us from city. We disassemble into atoms and reassemble somewhere else.

You can fly in a jet in the real world but that means dull waits at airports, the mystery of baggage claims and annoying travel to and from airports. It is worth looking down at the state from the plane windows.

Amtrak’s Coast Starlight takes fourteen hours if you’re lucky. If you go on a major holiday bring food. Sit in the observation car and see places you can’t see from a car. (Eds note: The dining car still has pretty good food as well).

The Pacific Surfliner starts in Union Station and goes to San Luis Obispo, where you get on a bus and get off the bus at the Ferry Building. That takes twelve hours. There’s also a way through Bakersfield, which involves two buses and the San Joaquin train: nine hours.

Greyhound buses travel from East 7th Street, at the bottom end of downtown

Los Angeles – the first terminal was at 560 South Los Angeles Street — 9 hours and 25 minutes.

Driving through the Central Valley: 5 hours and 36 minutes. It is hard not to fall asleep while driving through the Central Valley. This journey can mean a blizzard on the Grapevine and tulle fog in winter with dangerous driving conditions or miserably hot coma-inducing episodes in summer. Spring isn’t bad. It takes me eight hours.

Driving along the coast: six hours and 38 minutes. I have been stuck on the 101 from downtown Los Angeles to Ventura for six hours and 38 minutes in heavy traffic and I do not believe Google maps.