Bob Adelman, 85, Is Dead

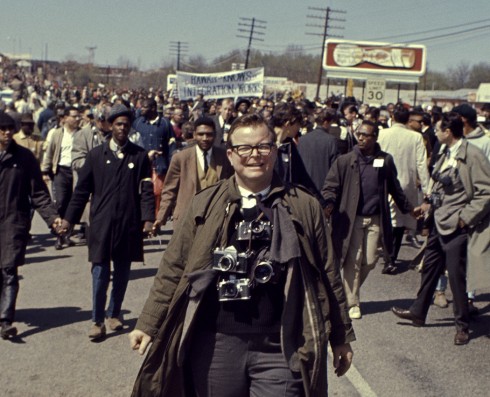

Bob Adelman, with marchers in Lowndes County on March 24, 1965 during the Selma-to-Mongomery march. ©Bob Adelman

By MARY REINHOLZ

The first news stories out of South Florida were sketchy. They raised troubling questions about the passing of renowned photographer Bob Adelman, a friend of this reporter for many years who was found dead March 19 at his home in Miami Beach. He was 85 and had been living alone for a month since the departure of a long time live-in girlfriend, a source said.

Adelman, a twice divorced native New Yorker, was best known for his pictures of the early civil rights movement, especially an iconic photograph he took of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering his 1963 “I have a dream speech” at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. He went on to chronicle a wide swath of American society over the next six decades, ranging from the world of high concept pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein to the seamy underground scene of hustlers and sex clubs in Manhattan.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivering his “I have a Dream” speech in 1963 at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. ©Bob Adelman

According to early reports from the Miami Herald, police cordoned off his art deco house with yellow crime scene tape and began interviewing neighbors after he was discovered unresponsive by a friend at 3 pm in the afternoon. He had a head wound, which fueled speculation of foul play. Other reports stated he had died of natural causes.

In the days that followed I prepared an obituary for The Villager, a weekly newspaper that covers the downtown New York neighborhoods where Adelman had worked and lived since the 1960s. I also contacted the Miami-Dade County Medical Examiners office about the precise cause of his death. In response, Darren J. Caprara, director of operations for The M.E., wrote back that Adelman had suffered a heart attack “and then injured his head when he fell.” He attributed his death to hypertensive and arteriosclerotic heart disease.

Several of his colleagues said Adelman had kept working up until the time of his demise. He was also a prolific book packager on diverse subjects, producing the bawdy “Tijuana Bibles-Art and Wit in America’s Forbidden Funnies, 1930s-1950s,” and put together many books with the Life magazine imprint and also his own. These included coffee table books on Hollywood royalty like Grace Kelly and Frank Sinatra. I was a California girl new to Manhattan when we first met in 1972 shortly after Adelman had published (with writer Susan Hall) a best seller called “Gentleman of Leisure.” It was an investigation into the shadowy turf of a dapper pimp named Silky and his “family” of adoring prostitutes who kept him groomed in three- piece suits and wide brimmed fedoras.

At that time, Adelman looked like a chubby blue eyed cherub in his safari suit. He had studied law at Harvard and held a masters degree in philosophy from Columbia University, specializing in aesthetics. He later explained to interviewers that he became interested in the civil rights struggle from watching Billy Holiday and Charlie Parker perform in jazz spots in nearby Harlem. He had also read about the sit-ins down South and found a cause he could believe in as a young man with no religious convictions.

“And of course the treatment of the demonstrators was very disturbing to me, and their courage was very moving,” he told a reporter for the New York Times in 2014. “I was a political idealist, so I went on a Freedom Ride to Maryland and eventually I became the National photographer for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and I worked with SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) too. For me to get involved in something, I had to see some purpose in it. I realized that my involvement would be very dangerous, but I had a long think with myself, and decided that this was something worth risking your life for. The photographs were very important. They were used as evidence in court cases, they were used to raise money for the movement.”

Early on in our friendship, Adelman struck me as your quintessential New York Jewish intellectual turned artist and activist. He was a Brooklyn born son of Eastern European immigrants who grew up in Far Rockaway, Queens during the great Depression and attended Stuyvesant High School,a premier public school for gifted students (all boys back then). He had a mischievous sense of humor and engaged in sexual banter that was disturbing to me at times. But it never went anywhere and eventually his jokes subsided. We worked on a couple of projects together, one involving a feminist group. And we kept in touch after he relocated to Miami Beach in the wake of Lichtenstein’s death in 1997.

Along the way, his photographs appeared in numerous museums, among them the Smithsonian and the Museum of Modern Art. He won awards, such as a Guggenheim Fellowship.

When he died, I had stark nighttime images of a vacated grocery with all the shelves stripped bare. For me, Adelman was also a big daddy figure, a superman at the supermarket who always seemed to be there for this lowly scribe, offering sensible career advice, recommending prospective employers he knew, warning about a sportswriter boyfriend who had broken my heart. I wondered why he chose to live alone after the breakup of a relationship with a much younger woman.

Stephen Watt, manager of Adelman’s archives in Miami Beach, insisted that his late boss had no problem living alone “and he rode his bicycle to the beach” on the day before he died. He described him as “one of a kind” and “much larger than life,” adding that his books included a tome on Soviet military power and one on the Bill of Rights, published with Ira Glasser, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union in New York for 23 years.

Watt noted that Adelman was planning on conducting his “last” lecture at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. on Bastille Day, July 14. He had been appointed a consulting photographer and lecturer at the Library in 2014. Adelman’s first lecture was on his book, “Andy Warhol’s first Fifteen Minutes of Fame,” during the Library’s National Book festival.

Andy Warhol at Gristedes market in New York City, 1965. ©Bob Adelman

During his early career, Adelman spent considerable time at Warhol’s notorious Factory, photographing the pop art eminence reclining languidly on his red couch and also while making several films.Adelman asked Warhol to accompany him to a Gristedes supermarket in Manhattan, so he could shoot him shopping for cans of Campbell’s soup and filling his shopping cart with boxes of Brillo, according to a website for the Westwood Gallery in SoHo, which held an exhibit of Adelman’s civil rights photographs in 2008 to mark the 40th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act. http://www.westwoodgallery.com/artists/bob-adelman/Writing

James Cavello, a founder and owner of the gallery, said he had been in contact with Adelman earlier this year. “He was here in New York, staying at the Waldorf, and talking about his print of of Roy Lichtenstein’s ‘Greene Street Mural,'” Cavello said, referring to Lichtenstein’s 96 and one half foot long masterwork that Adelman had photographed in 1984 at Leo Castelli’s gallery on Greene Street, also in SoHo.

“He was in the belly of the beast, in the middle of what was going on,” Cavello said of Adelman during a telephone conversation. “Whether it was civil rights or gay rights, Bob was there. He was amazing. How many individuals do you know who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King? He was a white Jewish photographer and he also photographed Malcolm X.”

Asked what it was like to work with Adelman, Cavello laughed and said, “Like most photographers, he was difficult. But he was a true artist with great integrity.” He plans to host a memorial for him when the Westwood Gallery moves to the gentrified Bowery in June. Adelman’s 72 inch long print of Lichtenstein’s “Greene Street Mural” will be on display.

Cavello attended a graveside funeral for Adelman held March 23 at Mt. Ararat Cemetery in Lindenhurst, Long Island. Survivors include his daughter Samantha Joy Reay, by his first wife, Trudy Vine; a sister, Delores Feldman, and three grandchildren.

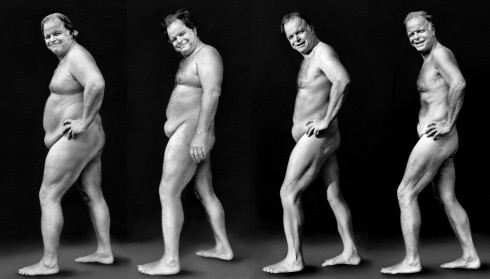

Although Adelman always seemed laidback and casual in his dealings with me, speaking in a soft voice bordering on a drawl, others who knew him say he was a driven and complicated man. He didn’t drink or smoke but struggled for years with his weight and photographed his “shrinking” size in nude pictures he took of himself for Esquire magazine. He once said in an interview: “When I photographed, I was intent on telling the truth as best I saw it and then to help in doing something about it.”

Famed novelist Ann Beattie, who was a friend and collaborator with Adelman since 1981 when she lived in Manhattan, said in an email that the quirky photographer was “not an easy person, but he was nevertheless his own person, and he was amazingly hard working, up until the day he died, and he always aspired to a more equitable balance of power. His convictions about social justice were formed early, and in a way everything he did touched on and elaborated his beliefs.”

Beattie wrote a revised introduction to Adelman’s updated 1990 book, “Carver Country,” which featured the gritty writings of Raymond Carver. Adelman illustrated them with his own photographs of Carver’s blue collar terrain. She said they “depicted not just the man (Carver) but the interrelationship of the landscape he inhabited and its influence on him.”

In response to a question, Beattie said Adelman was a socialist and also a lonely guy, known for making outrageously provocative comments that “justifiably” offended some women.

But not Lorraine Anne Davis, an appraiser of fine art photography based in Houston, who wrote in response to my obit in The Villager: “I was never offended when Bob flirted with me. He was just so damn funny and he never, ever stepped over the line.” She noted that when word came of his death, “I burst into tears. As James Taylor wrote…”‘But I always thought I’d see you again.'”

Adelman considered himself as something of a self-taught photographer. He had taken some photography classes at the New School in Greenwich Village from Russian photographer and designer Alexy Brodovitch, the legendary art director at Harper’s Bazaar, and became a protege of Jacques Lowe, official photographer for President John F. Kennedy.

One of his best known photographs shows four civil rights activists holding hands in Birmingham, Alabama, as police sprayed them with water cannon to clear the streets in 1963. In a 2008 interview with NPR, Adelman recalled that the hoses were so powerful they could “skin the bark off a tree.” He observed that a “single individual could not stand up (to the cannon). But as a group they could. And it became emblematic. The picture was actually part of the recruiting for the March on Washington.”

In those days, Adelman was often at the side of Martin Luther King and had access to other prominent civil rights activists like the writer James Baldwin. He got assignments from top publications such as Look, Life, and the New York Times Sunday Magazine. Many of his pictures from that era were collected in his 2007 book, “Mine Eyes have Seen: Becoming a Witness to the Struggle for Civil Rights.”

The title of that book shows a spiritual side to Adelman who, despite his atheism, felt his photographs of the civil rights movement were his way of “doing the Lord’s work” by exposing the underlying cruelty and injustice of segregation.

Although he seemed mainly focused on his work, Adelman had a strong sense of family that extended to his friends and collaborators. New York tax lawyer David Leavitt, 39, a son of Susan Hall who had partnered with Adelman in publishing six books after they both produced a series of articles on prostitution for New York Magazine, said that Adelman was like a father to him “for all my life. I loved him. He was incredibly generous and loving and good to me in many ways.”

Leavitt recalled how he would spend weekends with Adelman as a child on his lower Fifth Avenue studio where he worked and lived. He would join him on Sundays when the photographer would play chess with Roy Lichtenstein. He said Adelman developed films overnight “and he taught me how to print. He had a lot of energy and unparalleled intellect.”

John Loengard, a former picture editor at Life magazine who worked with Adelman during the 80s and also taught with him at The New School and the International Center for Photography, observed: “I never heard him say anything that was not intelligent.”

He noted that Adelman also had a special instinct about people and a “wonderful way of being able to get them to re-enact events that we would put in the magazine.” One of the most memorable of those, Loengard said, was when Adelman photographed a state trooper from Texas who angrily recalled being “handcuffed to Lee Harvey Oswald when Oswald was shot (by Jack Ruby in Dallas).”

Asked how Adelman was able to get close to such extraordinary characters, Loengard replied: “Most of us are too humble to ask, but Bob never hesitated to make contact. He was very sweet and had sides to him that I didn’t know about.”

Adelman was a gracious host to me and my cousin Pat Sullivan and his wife Lisa Lee when we visited his home in Miami Beach after touring the Everglades in 2004. He lived well. I remember the marble floors on the first level of his house and the pricey hard bound picture books he gave us before we left. Lisa was particularly impressed by Adelman’s photos of the Nobel Prize winning Irish playwright and novelist Samuel Beckett. The two of them started quoting fragments from his “The Unnameable” almost in unison: ” You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

Self-portraits of Bob Adelman losing 100 pounds from 1979-80, Esquire. ©Bob Adelman

Ann Beattie said she and her painter husband Lincoln Perry met with Adelman about a month and half before he died at a restaurant in Islamorada, about half way between his Miami Beach home “and our place in Key West.” After their meal, she wrote, Adelman decided to sit looking at the ocean that day. “He was humbled by things larger, greater than mere humans–though at the same time, he was totally attuned to particulars and to details,” she wrote. “He knew magnificence when he saw it, whether it be a landscape or a person. And he worked and had projects up until the moment he died–so many of them still putting forth his expressed and silent hope that we might still, as a society, draw together. Do better. In his own way, he certainly knew how to be someone’s friend.” #

*

Another version of this story first appeared March 31 in The Villager, a New York City weekly newspaper.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.