AWAITING MY OLD FRIEND BEN’S DAILY VOICE

By Bob Vickrey

None of us standing on the shore should have been surprised when a large pod of dolphins surfaced near the paddle boarders who had formed a circle just offshore.

Our friend Ben’s ashes were being scattered in the emerald-green Pacific waters less than a half-mile from his home. We had assembled for a modest memorial service at Will Rogers State Beach in Pacific Palisades, California to remember and honor a writer who had left a deeply felt legacy of not only his written words, but also for the impact he had made on the lives of those who knew him.

It seemed so fitting and proper that the dolphins should surface in time to welcome the man who had enjoyed a life-long love affair with the ocean they had shared. Ben was a storyteller whose very source and inspiration for writing had been the sea itself.

I find it a bit uncanny that after losing my friend over a decade ago, that I still chuckle over something he said all these years later. Ben took a rather light-hearted view of the world he lived in, and lingering memories of his words still lift my spirits as I go about my day. Perhaps, I had been wrong in my doubt about the possibility that the abiding presence of a friend could make such an indelible impact on one’s life.

Ben Masselink was a television screenwriter, novelist, newspaper columnist, and teacher whom I met after moving to Los Angeles where we shared an office complex in our suburban village. He had a warm and charismatic personality, and his humor and genuine kindheartedness attracted people of all ages.

Ben was tall and thin, and easily recognizable as he strolled through the village wearing his walking shorts, flip-flops, and his signature red ascot tied haphazardly around his neck. He always had a string that was visible above the collar line of his pull-over shirt. A short pencil was attached to the string under his shirt for note-taking in case someone said something that triggered an idea he liked. In his back pocket he reached for a folded, often slightly damp (from his morning swim) index card.

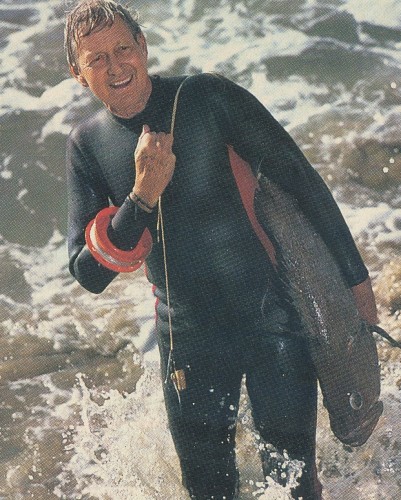

His many newspaper columns reflected his simple storytelling skill, and he found an ideal audience with those readers who wanted an escape from the stark headlines on page one. His tales usually involved his wife Dee, or of a lifetime of rich experiences at his ‘other home’—those chilly compelling waters of the Pacific. He was an avid swimmer, body surfer, and fisherman whose decades of outdoor beach life had inspired his writing.

Those note cards often found their way into unsuspecting places: on your front door, under your car windshield wipers, or occasionally mixed in with the daily mail. One read simply: “If Dee had married Don Ho and you passed her walking along the beach, you’d likely greet her with a Hi Dee Ho.” Another read: “If Fredrick March had married Tuesday Weld they could have named their daughter Tuesday March the 2nd.” When he had a funny thought, his friends got to enjoy the moment with him.

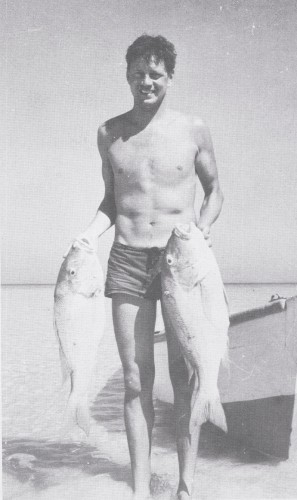

Ben had attended DePauw University in Indiana and joined the military service during World War II. As a sergeant in the Marines, he served in the Marshall Islands and Okinawa. He became founding editor of the USMC Pendleton Scout and somewhere in the South Pacific he decided that he wanted to become a writer.

He returned to Southern California after the war and became a tile-setter’s helper, but also wrote stories for magazines like Collier’sand the Saturday Evening Post to help support himself. He wrote a series of adventure novels including: The Crackerjack Marines,The Danger Islands, and The Deadliest Weapon.

Ben’s many television credits reflected an easy-going, elegant, but often irreverent style. He wrote many of the scripts for shows like: Marcus Welby, M.D., Dr. Kildare, Hawaii Five-O, and Barnaby Jones. He worked on projects for producers Roy Disney, Robert Greenwalt, and Aaron Spelling.

He reconnected with the noted fashion designer and artist Jo Lathwood, whom he had met before he went overseas and began a long relationship that lasted more than two decades. They lived together in her apartment in Santa Monica Canyon.

Jo’s art gallery in the canyon had become quite the Westside social spot for artists and writers. She and Ben hosted many a party there featuring star-studded guest lists. Acclaimed English writer Christopher Isherwood, artist Don Bachardy, and glamour photographer Peter Gowland regularly attended her soirees. Director Elia Kazan and playwright Tennessee Williams were often seen among the crowd. On several occasions, Dorothy Parker flew in from New York to join the party.

At one particular party, Ben was rather surprised to find himself engaged in conversation with actor Clark Gable who asked what he did for a living. Ben told him he was a tile-setter and proceeded to show Gable his work in the bathroom of the studio. Gable seemed fascinated with the skill and wanted Ben to teach him the details of tile work. Ben never mentioned to Gable that he was also writing and publishing books.

In the mid-1950s, Ben was swimming in the ocean at State Beach in Santa Monica when he literally swam into a young woman named Dee who would eventually become his wife. Dee Humphrey was a beautiful and petite ballet dancer who was then married and had an infant daughter.

Their meeting blossomed into a friendship spanning many years, and when Ben received word that Dee had separated from her husband, he wrote her a long letter declaring his undying love for her. Dee seemed stunned by his rather shocking admission, but found that she was more receptive to his proposal than she had expected. They eventually moved to Venice and married as Ben became a second father to Dee’s young daughter Heather.

When I was invited to their Palisades home overlooking Temescal Canyon in the 1980s, you could always count on the presence of a lively group of writers and raconteurs at one of the many dinner parties they hosted. That is where I first met writer Bob Pirosh who had once written for the Marx Brothers when he was a very young man. He could mimic the cadence of Groucho’s speech and by the time I left the party, I thought I’d had dinner with Groucho himself. Ben always encouraged storytelling at his table, but there was no one better at telling a story than the host himself.

He taught creative writing for 20 years at the University of Southern California where many of his students hung on his every word and followed him like he was the Pied Piper of Hamlin. He offered them encouragement while warning them of the sobering realities and challenges that came with the writing profession.

Ben was a man who had always loved people, the sea, and travel. However, on the day he turned 70, he declared in his newspaper column that there were no longer any excuses necessary in turning down an invitation to a social gathering. He wrote that a simple: “I don’t want to go” should now suffice. Ben decided he had officially become a ‘curmudgeon.’ He considered his new option one of the few advantages of getting old.

In later years, he was happy to be at home with Dee and near enough to the water where he could take his morning swim. He continued to write his column for a local newspaper entitled, “Tales of an Ancient Beachcomber.”

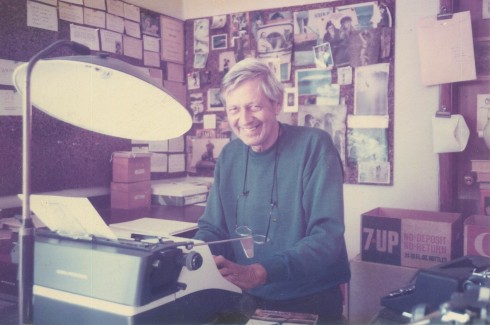

Ben always seemed a contented man when surrounded by his Underwood, Royal, and various other vintage manual typewriters in his cluttered office. Ben never once considered converting to a computer and giving up his loyalty to the manual typewriters he had written on since WWII. Reams of finished work were stacked in boxes along the walls that reached halfway to the ceiling. He claimed that all the boxes were organized with his unique personal system and that he could find any document that he had ever written. I tested him once. He found the story.

One of those typewriters (a Facit) sits on a bookshelf in my study where I write today. Dee had given it to me after Ben’s death in January of 2000. His weathered green beach hat still covers the keyboard. A yellowed sheet of copy paper is still embedded in the carriage. It was likely one of the last pieces he had worked on before his death, but it was not a story for publication. Instead, it appears to be notes written to himself about pushing forward with his life and work.

“The end is nothing. The journey is all. Real success is in the work itself.” The message continued: “No regrets, no worries. Look on the lighter side. Most men are as happy as they make up their minds to be. Live now!”

I rolled the paper back into its original position in the typewriter carriage and carefully placed Ben’s floppy old beach hat back over the keyboard where it belonged. As I lingered in the room, I listened quietly for a long moment, then turned out the light and gently closed the door.

Bob Vickrey is a freelance writer whose columns appear in several Southwestern daily newspapers including the Houston Chronicle and the Ft. Worth Star-Telegram. He is a member of the Board of Contributors for the Waco Tribune-Herald. He lives in Pacific Palisades, Ca.