Tengo Kawana and Aomame’s Adventures in the World with Two Moons

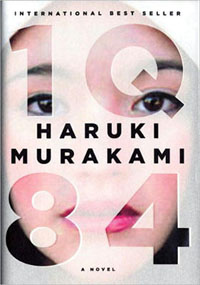

1Q84. By Haruki Murakami. Translated from the Japanese by Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel. Audible audiobook edition: 10-25-2011. Narrated by Allison Hiroto, Marc Vietor, and Mark Boyett. 46 hours and 50 minutes. Paper edition: 944 pages. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, October 25, 2011.

By Leslie Evans

I first encountered Haruki Murakami’s work only last year when I “read,” as an audiobook, as I do most fiction, his 1985 novel “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.” Literature began as oral storytelling and in our technological age it is to an important degree returning to those roots. It is common in works of fantasy for the conventions of the fantastic world, once established, to be presented with a strict faux realism to promote the suspension of disbelief. Murakami employs realism generously, but to a different end, long sequences of mundane detail are embedded in a world rich in surreal elements, whose rules and reasons are often never explained.

I first encountered Haruki Murakami’s work only last year when I “read,” as an audiobook, as I do most fiction, his 1985 novel “Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.” Literature began as oral storytelling and in our technological age it is to an important degree returning to those roots. It is common in works of fantasy for the conventions of the fantastic world, once established, to be presented with a strict faux realism to promote the suspension of disbelief. Murakami employs realism generously, but to a different end, long sequences of mundane detail are embedded in a world rich in surreal elements, whose rules and reasons are often never explained.

A common device for Murakami is to alternate chapters between two characters who are either intimately connected in some unknown way, or are the same person in different aspects. Hard-Boiled Wonderland concerns a nameless Calcutec, an encryption savant, who works for the System, a mysterious governmental agency tasked with keeping data secure. The Calcutec accepts an illicit job for a scientist who is perfecting technology to prevent sound from propagating (his daughter, when rayed by his device, can speak but no sound travels outward). The scientist’s laboratory is hidden deep in the sewers under Tokyo. This is the Hard-Boiled Wonderland. If it is bizarre the End of the World place is more so. The second character, in alternating chapters, also nameless, is a recent arrival in a strange walled town. No one who enters ever leaves. The town raises unicorns, who are left to die in the snow each winter. Every town dweller has had their shadow cut away from their bodies, the shadows soon dying, leaving the citizens with no shadow and, they say, no mind, but this seems to mean no affect, a condition that interests Murakami. This character, who has no memory of his previous life, is assigned to be a Dreamreader in the town library, where he spends his days placing his hands on the skulls of dead unicorns, which brings him visions that must be recorded. He makes secret visits to his dying shadow, which pleads with him for the two to try to escape.

We eventually find that the End of the World town is a construct inside the mind of the Calcutec, who in turn is informed that he has only days to live. Does the time his alter ego spends in the unicorn town come after his consciousness is extinguished in Hard-Boiled Wonderland so that is where he will go afterward, or do both of his variants expire when his time is up? It is never clear.

While the life of the Calcutec is frenetic, the chapters in the unicorn town are infinitely slow and meditative. The producers chose different readers for the two halves, the Dreamreader perfectly conveying the curious combination of a patient, memoryless man quietly exploring his new environment, and looking without haste for a way to escape it.

Murakami, who turns sixty-three in January 2012, is regarded as a postmodernist. He lived in the United States for nine years, between 1986 and 1995, where he taught writing at Yale and Tufts. He is criticized by the Japanese literary establishment for his many Western and American references. He has been prolific both as a novelist and as a translator, where he has done Japanese editions of F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Irving, Truman Capote, and numerous other authors. He has received many literary awards and prizes, but mostly from Western countries. Yet his most recent novel, 1Q84, sold a million copies in Japan the first month. It was published there in three hard-cover volumes in 2009-10. The English translation, by Jay Rubin and Philip Gabriel, runs to 944 pages. It was released in the United States on October 25, 2011.

1Q84 is a love story, an account of a ruthless religious cult, and a tale of parallel worlds, in which none of these terms match conventional expectations. As in Hard-Boiled Wonderland the chapters alternate between different characters; in the first two volumes, between the young woman Aomame, a martial arts and sports trainer, and Tengo Kawana, a math instructor in a Tokyo cram school who is an aspiring novelist on the side. In the third volume another voice enters, the morally and physically ugly Ushikawa, tasked by the cult with hunting down Aomame and Tengo.

The story takes place between April and December 1984. It begins with Aomame, thirty, in immaculate business attire, in a taxi caught in a traffic jam on a Tokyo elevated highway. Aomame means “green peas” (think of edomame, the green soybeans you get as an appetizer in Japanese restaurants), said to be a very unusual name in Japan. The cab radio is playing Leos Janacek’s 1926 Sinfonietta (now experiencing a surge in popularity due to 1Q84), which she inexplicably recognizes. We learn later that Tengo played timpani in a high school orchestra performance of this piece that Aomame knew nothing about. Ushikawa also listens to it, with a feeling that it has some significant meaning that he can’t quite grasp. The novel is full of these kinds of surreal illuminations.

Aomame, late for an appointment, steps out of the cab and descends an emergency staircase to take a subway to her destination. This marks her entrance into the parallel world she comes to call 1Q84, the Q standing for Question Mark. The title is also a pun in Japanese, as the pronunciation of Q (kyu) is the same as the number 9, so that spoken aloud 1Q84 and 1984 are the same.

Arriving at a high-end hotel, we learn that Aomame is a part-time assassin, there to kill a viciously abusive husband. Posing as a hotel staff member there to inspect the air conditioner, she stabs him in the back of the neck with a special ultrathin ice pick that leaves no mark.

Meanwhile Tengo has been serving as a volunteer reader for submissions to a literary award contest. He is strongly impressed with a novelette written by a seventeen-year-old girl, Eriko Fukada, who signs herself Fuka-Eri, also not a recognizable Japanese name. He proposes it to his editor, Komatsu, as a possible winner. Komatsu agrees but thinks the writing too unpolished. He persuades Tengo to secretly rewrite Fuka-Eri’s work in more literary style. This risky subterfuge works, the novelette wins first prize, then is published and becomes a best seller.

We are told that Fuka-Eri’s book is a surreal fantasy. It is about the life of a ten-year-old girl who lives in a rural commune in a world with two moons. She tends goats, and is blamed when one goat that is very important to the commune dies. She is locked up with the dead goat, where, during the night, Little People come out of the dead goat’s mouth and begin to weave an “air chrysalis,” a cocoonlike structure in which a replicant human grows, this image lifted from Invasion of the Body Snatchers, but somehow not as sinister when among the seven Little People, who leave the goat’s mouth at two inches high and grow to two feet, one is a “keeper of the beat” who says nothing but an occasional “Ho ho!” Charles Baxter in the New York Review of Books writes that “It is as if the Seven Dwarfs had gradually made their presence known and their powers understood in a novel by James T. Farrell.” Or Jack Finney!

This appears to be fiction until Aomame looks at the sky one night and sees two moons, the ordinary one, and a second, smaller, unevenly shaped, green moon. She is now in the world of 1Q84. The two worlds are almost identical, only a few small differences separate them: Tokyo police uniforms, a violent shootout between a cultish organization a few years back, and, mainly the Little People and the religious commune they dominate, a group called Sakigake (Forerunner), led, we eventually learn, by Fuka-Eri’s father.

The menace of Sakigake shadows the whole of the book. It is never clear if the Little People are good, evil, or neither. They come from yet another world. But through them Tamotsu Fukada, the group’s founder, is able to hear the Voice, which has become the most important thing in his followers’ lives. Publication of his daughter’s novel, which reveals the existence of the Little People to the world, even if no one takes it seriously, has stilled the Voice. It has created something like a disturbance in the Force in a Star Wars movie. This turns Sakigake’s attention toward Fuka-Eri, and, when they discover his role in the book, toward Tengo.

Aomame crosses paths with the cult through her work as an assassin for an elderly dowager, in which she sends the most brutal husbands of the refugees in the dowager’s home for abused women “to the other world.” It appears that Tamotsu Fukada, known to Sakigake only as Leader, is raping ten-year-old girls. The dowager puts him on Aomame’s transit list.

As children both Tengo and Aomame were denied love by their parents. Tengo’s mother disappeared when he was a toddler. His father, a remote and hostile man who made his living as a door-to-door fee collector for the NHK, the national television network, showed the child no affection, but dragged him along on his rounds to gain sympathy from deadbeat clients. Aomame’s parents belonged to a strict and self-isolating religious group, something like the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and they also forced her as a child to go with them on their door-to-door proselytizing.

The two children were in the same class in elementary school. Tengo was an athletic and math prodigy; Aomame, because of her unpopular religious clothing and manner was an outcast. They never spoke, but once only in the fifth grade she grasped his hand for perhaps a minute. Somehow the two fell in love at that moment. She transferred to another school, and 1Q84 takes up twenty years later, when they both come to realize that they have been carrying this deeply buried love around for two decades. They then begin to search for each other.

There are several murders in the course of the year. The one with the greatest consequences is Aomame’s murder of Leader. But nothing in 1Q84 is quite what it seems. A cardinal section of the novel is a long philosophical discussion Leader has with Aomame where she is alone with him in the hotel room where she had gone to kill him. He can read minds. He knows why she is there, and probably arranged it. He knows what Tengo feels for Aomame as well as what she feels for Tengo, even though the fated pair have hardly thought this through themselves. It is not clear that the ten-year-olds he has sex with are real people or the replicants created by the Little People, nor whether his actions have anything voluntary about them.

Throughout the book characters know things they had no means of knowing, or make deductions so improbably accurate that one has to suspect outside mental guidance. At other times they are, more realistically, frustratingly wrong in their surmises. There are occasionally scenes of explicit sex, but more often it will be descriptions of how Tengo’s older mistress holds his penis while they abstractedly talk about something else.

Through much of the book Aomame, after killing Leader, is in hiding from the cult, long stretches where the story is filled with the minutia of daily life in the confines of a single small room with the curtains drawn against the outside world. Similarly for Tengo, who spends a lot of time in his tiny apartment. We learn what he had for breakfast, how he cooked his dinner. When he is told his father is in a coma and dying in another town he goes there and long passages have him reading by his father’s bedside.

These scenes are reminiscent of the 1950s films by Yasujiro Ozu, such as Tokyo Story, depicting the extremely slow unfolding of daily life in tiny increments. In the case of Aomame and Tengo this is a rumination on loneliness and social isolation. The audio reading of this huge novel runs to just short of forty-seven hours. A substantial portion of that were these scenes in Tengo’s apartment and at his comatose father’s bedside, or at Aomame’s hideout. In the right frame of mind I found these prolonged interludes among the most pleasing parts, getting into another person’s skin at a time when nothing was happening and living it with them for a while. A little like an Anne Tyler novel.

For a while Fuka-Eri lives with Tengo, giving Murakami the opportunity to have a long digression in which Tengo reads her Chekhov’s book on Sakhalin, his 1890 nonfiction investigation of prison conditions on the Russian island just north of Japan. Most of Chekhov’s book deals with Russian prisoners, but Murakami has Tengo focus on Chekhov’s account of the indigenous Oroks. Even when the Russians built roads, the Oroks wouldn’t use them. They made their way across country, seeing no reason to become dependent on the alien construct. Fuka-Eri is fascinated by this point.

The air chrysalis fills with a replicant called a dohta. The dohta is linked mentally to its human model, the maza. The dohta is emotionally stunted. It is never clear if Fuka-Eri herself is the maza or a dohta. She lacks affect, is dyslexic, speaks little and then in an odd stilted way.

While her father, Leader, is genteel, his followers in Sakigake are coldblooded and ready to go to any lengths to reestablish a connection with the Voice of the Little People. They are the dark presence that defines the world of 1Q84, religious rather than Orwell’s political tyranny of that year. Murakami returned to Japan from America shortly after the Aum Shinrikyo cult’s sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway in 1995 that killed thirteen people and injured a thousand more. He interviewed 60 survivors of the attack, and then 8 members of the cult. He published the interviews in a nonfiction book, Underground. The Aum Shinrikyo interviews appeared separately in Japan but were included in the U.S. translation that appeared in 2000. The transmutation of Aum Shinrikyo into Sakigake also makes them less violent. Insofar as they are a threatening specter it is because they have frozen their lives into acolytes of the Voice, on which they have become desperately dependent for meaning.

Of their adversaries, the two lovers, Tengo was not even aware of the cult’s existence when he worked on Fuka-Eri’s manuscript. Aomame killed the cult’s founder while knowing almost nothing about its beliefs, believing him to be a sexual predator on young children, which was probably not true in the magical circle dominated by the Little People with its incomprehensible rules. Still, 1Q84 was a world to escape from no matter how much it resembled the ordinary 1984.

I have revealed more than I should of the story. I will leave unsaid what happens to Aomame and Tengo in what is coming to be regarded as Haruki Murakami’s masterpiece.