Honey explains the first roads through Los Angeles

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

Misperceptions about the role of the aboriginal people of Southern California in building the city begin with the road system, a system possibly 13,000 years old. Understanding the native American road system is a way to reveal that human behavior is not static, that the world of people is not one thing determined by immutable rules, but that it can be – and has been – much different from what it is now.

“In the New World,” wrote Carl Sauer in his 1932 monograph The Road to Cibola, “the routes of great explorations usually have become historic highways and thus has been forged a link connecting the distant past with the modern present. For the explorers followed main trails beaten by many generations of Indian travel.”

John W. Robinson wrote, “Winged Feet in the Dust: Long-Distance Trade Routes in Aboriginal California,” (The California Territorial Quarterly, Number 52, Winter 2002, pages 4 to 17.) Robinson traced those Native American routes for which written records remained. From Robinson’s descriptions and the map that Laurence G. Jones produced, the very traveled Mojave River Route descended through the San Bernardino Mountains into the San Gabriel Valley and crossed the Los Angeles River.

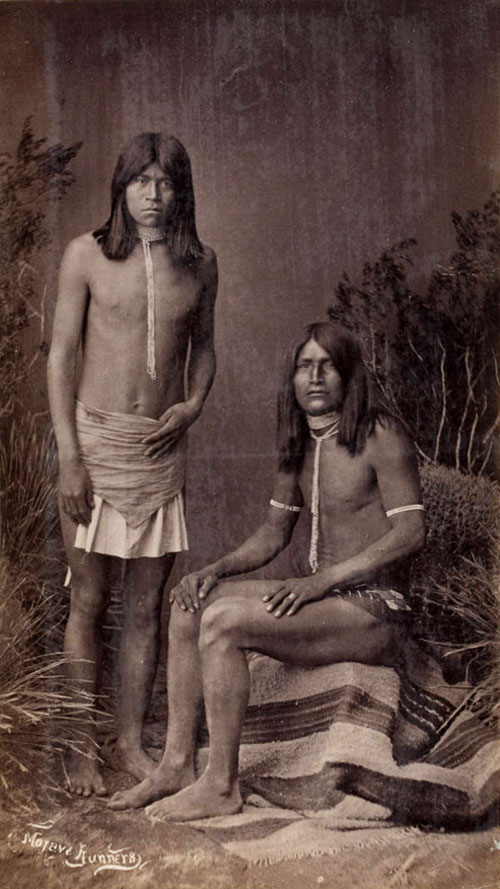

Mojave runners. Huntington Digital Library.

- Frank Randall photographed two young Mohave runners sometime between 1883 and 1888. (The photograph is found in the Huntington Library digital archives.) Mohave runners carried traded goods in baskets on their heads and also baskets on their backs connected with twine ropes to their heads. They traveled sixty miles a day. Long-distance elite runners today, carrying bottles of water, can run up to 100 miles a day. Indian runners did not carry water. They did not have a carbohydrate-based diet.

That route was probably the route that the first Europeans in California used to get to and then to ford the Los Angeles River. The place where the native people crossed the river was the place that the first Europeans used to ford the river because that was where the native road went.

We know that the Portolá expedition came along a “good road” from the San Gabriel valley campsite to what is today the location of the Downey Recreation Center in Lincoln Heights, camped there on August 2, 1769, and then used the native’s crossing to reach the western bank next to the last Elysian Park hill. We know this because Gaspar de Portolá and an accompanying Franciscan monk wrote descriptions of the route they took.

The Juan Bautista de Anza expedition probably took the same route across the river and later Alta California’s first governor Felipe de Neve probably followed the same route and forded at the same place. That crossing place or ford is part of the reason Neve sited the future pueblo of Los Angeles where he did – where the Metrolink storage area is located on the western bank of today’s river, 1.25 miles east-northeast from the primary trading village of Yang-Na.

Mohave runners “covered vast distances to bring Pueblo pottery to the coastal tribes, and carried Chumash shell beads back to the Indians of present-day Arizona and New Mexico.” (Robinson, page 8).

Robinson describes three major trail systems – the Mojave, Halchedhoma and Yuma that reached the Pacific coast. Additionally, “A multitude of foot paths followed every watercourse, went up every canyon and crossed every pass, joining almost every tribal group who lived in the vast coastal, valley, mountain and desert regions.”

The 10 freeway now traverses the San Gorgiono Pass. The western end is today’s city of Banning. In 1852, a writer for a San Francisco newspaper described the portion of the trail from the San Gorgiono Pass:

“The earth is worn deep, and along its course the surface is strewn with broken pottery. In may of the soft rocks the imprints of the feet of men and animals are plainly visible. The road is not much over a foot wide, and from it branch off side-paths leading to springs or other sources of water…” (Robinson, page 8). That description may well have also fit the road that the Spanish took from the San Gabriel Valley to the Los Angeles River.

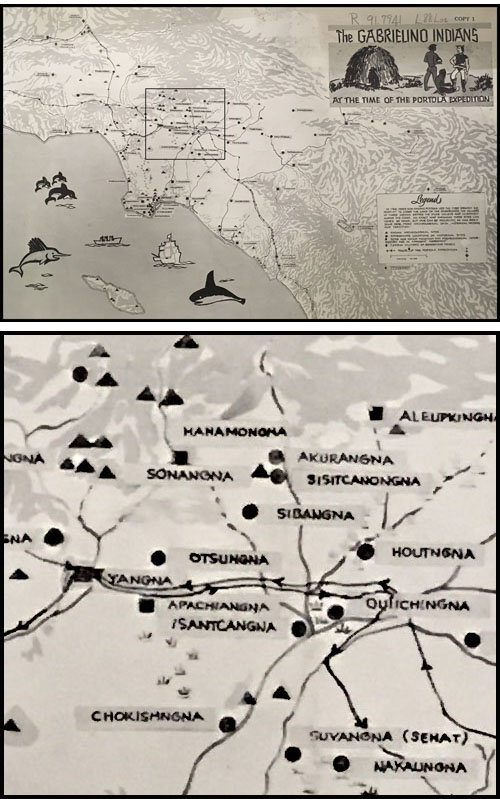

The map that accompanies this essay shows some of the trails used by the Tongva people at the time the first Europeans traveled through California. The Southwest Museum in Highland Park prepared the map from archeological data, historical records and tradition. The route sketched on it with arrows is the route of the 1769 land expedition and also of the 1770 return trip.

It looks from this map that the expedition traveled north from San Diego on an Indian road – probably part of today’s 15 freeway — that took them into the San Gabriel Valley and then they camped for two nights and then traveled west perhaps 13 miles along a route that is probably Mission Road to Downey Avenue and across the Los Angeles River along what is more or less North Broadway through New Chinatown to the Civic Center, where the primary trading village of Yangna was located. From there the expedition went along what is today Wilshire Boulevard past the tar pits to West Los Angeles, and then over the Sepulveda Pass through the eastern part of the San Fernando Valley along what is today the 405 to the five and then to Castaic and then west to Ventura on what is today Route 126.

On the way back, the Spanish explorers took a shorter route on what looks like Ventura Boulevard to Cahuenga (the 101 to Franklin) back to Yangna, back over the river to Ouichangna and then took a shorter route back to San Diego, which looks like today’s 5 freeway for part of the distance, and then joining the first route at a village named Hurrukngna. (The Tongva Nation Map compiled by Militant Angeleno places the village of Hutukgna at about that location, which is today’s Anaheim, so the first Spaniards in California got as far as where Disneyland is now before connecting up with their first road to return to San Diego.

The Southwest Museum map is a little misleading; that is, according to Professor Bolton, the expedition went west as far as Santa Monica, and then double backed to the Sepulveda Pass (the 405). The map of The Gabrielino Indians at the Time of the Portola Expedition does not show that they traveled to the beach before heading over the Sepulveda Pass.

The Southwest Museum map may be seen at the Los Angeles Public Library in the history department of the Central Branch, and in several other libraries in California.

The Southwest Museum map appears in Bernice Eastman Johnston’s California’s Gabrielino Indians, published by the Southwest Museum in Highland Park in 1962.

From the prefatory materials in Johnston’s book, it appears the map is partly based on Alfred Kroeber’s 1925 Handbook of the Indians of California. The map author or authors then superimposed over the Indian roads the route Spanish borderlands historian Herbert Bolton annotated from his translation of Father Juan Crespi’s diary in Fray Juan Crespi: Missionary Explorer on the Pacific Coast, 1769-1774 (University of California Press, Berkeley 1927). The first Spanish march through the Los Angeles area begins on page 146

Kroeber (1876-1960) was the first professor of ethnology at U.C. Berkeley, and he wrote a stunning amount and formidable quality of work on California Indians, all of it now available on-line.

Kroeber believed the Gabrielino cultural pattern encountered by the Spanish in the eighteenth century had crystallized as early as 1200 AD and that shortly before the Spanish arrived on land in 1769, the population was about 5,000. He began his work with the few remaining Gabrielino people with C. Hart Merriam in 1903. Kroeber and other researchers also drew on Hugo Reid’s writing. Reid’s wife Victoria was a Gabrielino, probably born in what had been the primary trading village of Yang-Na, which was located where today’s Civic Center is in Los Angeles.

The Gabrielino Indian trails at the time of the Portola expedition. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library. Above: the full map. Below: Detail of the area around what is now Downtown Los Angeles, marked with a square on the larger map.

Don Benito Wilson’s advocacy for protection of the remaining Indian people in Southern California also underlies some of the Kroeber’s research.

Kroeber concluded (page 621 and following of Handbook), that the Gabrielino were the wealthiest of all the Shoshonean people in California. Their influence spread from their villages on Santa Catalina and San Clemente islands as far south as San Diego to the interior Luiseno people in today’s Riverside County and up into the Oakland estuary – Lake Merritt today.

Kroeber wrote: “Between the coast and interior trade was considerable. The shore people gave shell beads, dried fish, sea otter furs, and soapstone vessels.

They received deerskins, seeds and perhaps acorns.” (Handbook, page 630). The works of later ethnologists and archeologists reveal the native people also exchanged pottery, woven textiles, dried fish, seaweed, obsidian, and vegetables, like corn and squash, that traveled well. The extensive trade system softened periods of environmental depletion and exemplified cooperative human behavior.

Kroeber mentions that the first contact between the Gabrielino and the Spanish was in 1542, when Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo set foot on California soil, and again in 1602, when the Gabrielino received a visit under Sebastian Vizcaino. The Spanish considered the Gabrielino people a special race of “white Indians” because of their light skin color.

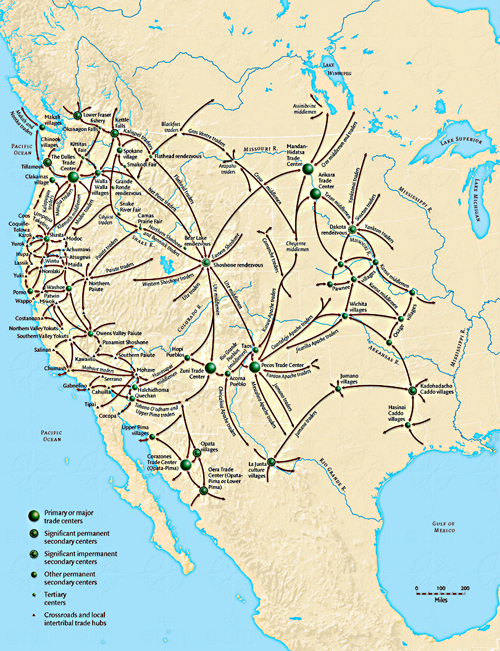

California abalone shells from pre-contact periods reached as far northeast as today’s Wisconsin. The most significant trade routes to and from and with California may be seen in the map from the Smithsonian that accompanies this essay.

Smithsonian Institution map of native American trade routes through a little of Mexico, some of Canada and the United States.

The English translation from the Gaspar de Portolá diary entry for August 2, 1769 is: “We proceeded for three hours on a good road, and halted near a river about fourteen yards wide.[1] On this day we felt four or five earthquakes.”[2]

The river that the expedition crossed on August 3, 1769 was today’s concrete channel through which water runs, which we call the Los Angeles River.

Father Crespi, one of the two Franciscan padres that accompanied the expedition, named the river El Río de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles de Porciúncula.

On the return trip through what is now the City of Los Angeles in January 1770, Portolá camped at about the entrance to the Hollywood Freeway on Franklin and went from there to what is now the unincorporated area of Bassett.

No one wrote how wide the river was on January 17, 1770, when the expedition returned from its exploration through Alta California along the coast and then north-northeast to today’s city of Antioch on the Delta. Portolá merely wrote: “The 17th we proceeded for about five hours, making the same distance as in two marches on the previous journey and came out on the Llano de la Puente.”

Llano de la Puente means “plain of the bridge.” At the end of July 1769, the expedition members had built a temporary bridge to cross the miry San Gabriel River. Today, the location is the city of La Puente. In 1769, it was the Tongva village of Awinga.

Friar Juan Crespi wrote: “We crossed the plain in a south-easterly direction, arrived at the river and forded it….”

The expedition consisted of 64 persons that had set out from San Diego on July 14, 1769, and it included two personal servants, two Franciscan priests, 27 cuera – leather jacket soldiers – an engineer/cartographer, 15 Indians from Baja California, and 7 muleteers. Most rode horses. The mules were pack animals. Baja Indians had linguistic and ancestral ties with Alta California people in the Los Angeles region.

They all proceeded on “a good road” according to Portolá’s diary.

In April 1770, Portolá led a second, smaller expedition from San Diego to Monterey. He followed the same route as he had followed on the January 1770 return trip.

The San Francisco Colony led by Juan Bautista de Anza followed what appears to be the same road as had the Portola expedition.

On February 21, 1776, Anza wrote “I set out on the regular road to Monte Rey, which we followed for a little more than a league to the southwest. Continuing for another league to the west-southwest (Friar Font, who accompanied Anza, wrote that the journey was directly west after they had traveled for a league to the southwest.) we crossed the Porciuncula River.”

In 1776, the regular road was very likely the good road. Anza left the San Gabriel Mission; the mission had been moved to its present location – now 428 South Mission Drive — in 1775. Spanish borderlands scholar H. E. Bolton located the Portola campsite at a place a little west of Alhambra. The two expeditions started, that is, at about the same location before traveling towards the Los Angeles River.

“Los Pobladores” – descendants of the fist settlers – annually celebrate the city’s 1781 birthday by walking from the San Gabriel Mission to El Pueblo. Actually, the settlers came in two groups, rather than one, so it was not one walk.

At the end of the walk, Los Pobladores arrive in the plaza near Olvera Street. The plaza downtown was not laid out until sometime between 1825 and 1830. In 1781, the edge of the Tongva village of Yang-Na occupied that area, and the people spoke a Uto-Aztecan language. Los Pobladores arrive at the wrong location.

Los Pobladores also travel along the wrong road to reach the wrong place to celebrate the birthday of the City of Los Angeles. So long as the City continues to celebrate the wrong road and the wrong beginning, with Chilean flautists playing Andean music and Aztec dancers in feathered headdresses stamping out whatever it is they stamp out in the plaza, the real people that built Los Angeles remain forgotten.

Other sources:

Aboriginal California Three Studies in Cultural History (The University of California Archaeological Research Facility, second printing 1966), James T. Davis, “Trade Routes and Economic Exchange Among the Indians of California.”

https://www.desertusa.com/desert-trails/native-americans-trails.html. Jay Sharp, “Native American Trails.”

Archival records in Seville showed that the first “Spanish” settlers were mostly mulatto, Indian, African, and Mestizo. So far, I haven’t found which Mexican native people contributed to the dna of the pobladores. Many came from Sinaloa. I recommend Ralph L. Beals, The Acaxee, A Mountain People of Durango and Sinoala (University of California, Berkeley 1933), Lesley Byrd Simpson, Studies in the Administration of the Indians in New Spain (University of California Press 1934), A.L. Kroeber, Uto-Aztecan Languages of Mexico (University of California Press 1934).

- W. Robinson Los Angeles from the Days of the Pueblo (Revised with an introduction by Doyce B. Nunis, Jr.) (Published by the California Historical Society (1981). Imagination fills in the gaps of knowledge. Robinson, an outstanding amateur historian, wrote, at page 9, “In 1815, because of severe flooding, the site was relocated just northwest of the present-day Plaza, and later moved to its present location.” This statement, which those people that even ask the question “where was Los Angeles first located?” believe to be correct, is imprecise, and the imprecision is important. The settlers outgrew the original site by 1790. There were only 12 areas designated as home sites around the first plaza.

Subsequent settlers and descendants of settlers built adobes along the mesa above the first agricultural fields along the bottom of the Elysian Park hills – today’s Chinatown – moving gradually to the southwest. They had built homes into what had been Yang-Na before today’s Olvera Street plaza was laid out. The residents collected funds to build a church beginning in 1811, and Fr. Gil from the San Gabriel Mission laid the cornerstone for the foundation of the church in 1814, a year before the 1815 flood. The 1815 flood as well as the 1801 flood inundated the agricultural fields established after 1790 in the area north of today’s Broadway Bridge. Those fields became contaminated with river sand, and the residents of Los Angeles abandoned them for agricultural purposes. There is no information – other than partially remembered anecdotal information – about what happened to the original plaza and the original adobe houses. The decaying remains of the pueblo proper could have existed until 1876, when Southern Pacific changed the landscape of that area to build train tracks.

[1] The river was actually rather wider than the English translation indicated. The Spanish version of his entry indicated the river was 14 pasos across, not yards. A “paso” was about 55 inches. The river was 770 inches — 64 feet or 21 yards — across in August 1769.

[2] Diary of Gaspar de Portolá During the California Expedition of 1769-1770, originally published in the Academy of Pacific Coast History, v. 1, no. 3 (October 1909). Edited by Donald Smith, Assistant Professor of History and Geography, University of California, Frank Teggart, Curator of the Academy of Pacific Coast History, publisher Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. The editors obtained the manuscript from the Bancroft Library, at Berkeley. The manuscript arrived with other materials that H.H. Bancroft sold the university in 1905. The manuscript Teggart used was preserved in the Sutro Library, San Francisco. Bancroft obtained the manuscript from M. Alphonse Pinart, who purportedly obtained it from Mexico City on October 10, 1881.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.