How Important Are Flying Wings In These Coming Years Of City Planning And Grand Universal Design

By LIONEL ROLFE

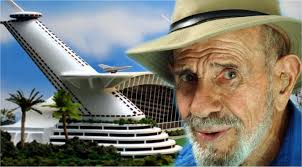

Back before the Golden State (5) Freeway was finished in the early 1950s, I had a mentor who owned a lab on Riverside Drive in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles. He was a short, dark man, a Turkish Jew born in Harlem in 1916 of parents from Istanbul and Haifa. Like his ill-educated parents, futurist Jacque Fresco had no verifiable college degree. But he had nonetheless become famous as an industrial designer, specifically for the flying wing aircraft that he helped create with Los Angeles aviation pioneer Jack Northrop. He was Aircraft Designer for the Northrop Division of Douglas Aircraft, Los Angeles, California, in1939. Fresco and Northrop had disagreements but they nonetheless worked together closely.

This March, Fresco, who has worked as both designer and inventor in several fields, turned 100 years old and the UN presented him with an award for his work in city planning. It was on this occasion that I talked with him.

I had first walked in Fresco’s lab when I was about 10 years of age—probably in 1952. Our discussion immediately took me back to meeting the flying wing guy.

I remember walking into that place, which always sent you through a kitchen full of good things to eat and then into a study full of several fascinating objects, including oscilloscopes, as well as a giant model of a fly that was several feet long. The place had amazing couches and beds where the students listened carefully to Fresco. During our last talk, Fresco surprised me by arguing city planning had become more important to people than flying around on flying wings and driving in curvy cars. He reminded me of a term that I first heard when I attended school at his lab. The word was “cybernetics” — the design of machines to make better machines than those produced by human hands. Fresco was certainly a pioneer of the idea of artificial intelligence, among other attributes. But at the heart of his thinking was cybernetics.

Like so many others in the ‘30s, he was a radical supporter of the Communist Party who later became a technocrat. Cybernetics became the ideology of technology.

By the time he was 14, Fresco had traveled the country, hopping freight cars heading away from the East Coast. As a technocrat his background became pure science. He had grown up in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of Brooklyn, mostly among Ashkenazi Jews — unlike him. He was Sephardi, while most people in the neighborhood who ate herring on the weekend were Ashkenazi, not like his parents who enjoyed beans and marijuana on the Sabbath.

In 1939 he left the coldness of the Northeast and headed toward Los Angeles. He never got a degree in physics or aeronautics. Formal education was “all bust for him,” a friend said.

By the time he hooked up with Northrop in the late ‘30 and early ‘40s, they were both working on the flying wing project for the Northrop Division of the Douglas Aircraft Co. The two men argued about their respective designs, but it was Northrop’s concepts that were commissioned and built. The Air Force grounded Northrop’s design after one of them crashed. Local news broadcaster Clete Roberts was a well-known public affairs commentator who went into the design aspect of the revolutionary aircraft, pointing out that Fresco’s designs were never tested as a result.

Fresco was not just my “flying wing” prefab guide maker—he was a man who wanted his students to understand the mechanisms that drove not only airplanes and cities, but also cars, trains and galaxies.

Nearly everything he emphasized were enemies of cybernetics of the ‘40s and ‘50s, a concept invented by Norbert Weiner at MIT, who considered it a formalization of the notion of feedback — something that occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause-and-effect that forms a circuit or loop — with implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, neuroscience, philosophy, and the organization of society.

Fresco was never a religionist. He was a mechanist, who saw mechanisms as the explanation for what made things happen throughout the universe, much as did Jacques Loeb, the German physiologist and biologist of the early part of the last century, a down-home mechanist.

The point of cybernetics was simply that it was a design that allowed machines—i.e. computers—to create new machines.

During our last talk, Fresco surprised me by arguing that perhaps city planning had become more important to people than flying around on flying wings and driving in curvy cars. He wanted machines to make better machines than those produced by human hands. Fresco was certainly a pioneer of the idea of artificial intelligence, among other attributes. So cybernetics was at the heart of his thinking.

At first he was a communist—like most others in his time—but he quickly became a Technocrat. He was more a scientist than a politician. He had grown up in Brooklyn, following science more than any other technique Most of the Jews in Brooklyn were Ashkenazi—he was a Sephardi, an Arabic kind of Jew. The Ashkenazi ate herring and smoked marijuana on Friday. But he was, as he said, more a scientist.

In 1939, he left the coldness of Brooklyn, and headed toward Los Angeles. He never got a degree in physics or aeronautics. Formal education was “all bust for him,” a friend said. But he got plenty of education from his time in Los Angeles and later Florida.

Fresco was never a religionist. He was a mechanist, who saw mechanisms as the explanation for what made things happen throughout the universe, much as did Jacques Loeb, the German physiologist and biologist of the early part of the last century. He was and no doubt remains a deep and abiding anti-mystic”

Among Fresco’s supporters was Earl “Madman” Muntz who wanted Fresco to create prefabricated industrial facilities—which his laboratory was. Fresco became an architectural critic for Muntz homes, designing low cost housing for the Muntz trend home. Muntz put up $500,000 for the design.

The lab was initially made of aluminum and glass at Stage 8 of the Warner Bros Sunset for three months. Although there was a lot of interest in the home, it never went anywhere. Muntz was born in 1914 and lived until 1897, used his oddball “Madman” person, using costumes, stunts and the like creating a 4-track cartridge that was a predecessor to the eight track cartridge developed by Lear Industries He created an alter ego who sold cars and television sets. He sold stuff from the 1930s until his death in 1987.

He was a pioneer with his oddball “Madman” persona Earl Muntz – an alter ego who generated publicity with his unusual costumes, stunts, and outrageous claims. Muntz also pioneered car stereos[1] by creating the Muntz Stereo-Pak, better known as the 4-track cartridge, a predecessor to the 8-track cartridge developed by Lear Industries.[2]

Fresco was not unlike Muntz. Many of those who disliked him were no doubt a bit turned off by his wearing a beard. Asked why he refused to shave, he asked his inquisitors why they didn’t just relent and allow their beards to grow. That was his spirit.

But those who disliked him were no doubt turned off by more than just his wearing of a beard. The style remained. As far back as the ‘70s, Jacque was interviewed by Larry King in a full interview. And there have been a whole series of documentaries and books since then.

Since the time I got to know him, Fresco developed a strong following—including being a speaker on utopian studies in Florida as well as a guest lecturer on future planning in Dubai. He was a speaker at the Technical University in Vienna, and a guest speaker at conference in china and Nigeria.

The Venus Project was developed with his associate Roxanne Meadows for which a 25-acre facility was developed and national and international attention has been obtained.

This year a large contingent of filmmakers showed up to interview me about my early memories. They were held by Rob Shan Lone, a London-baseball webographer and filmmaker. The gang took over my living room in an apartment near where the old lab was a built. I talked my way crazy. The film is due out next year, and it is called “Fresco.”

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.