Honey Talks About Where Los Angeles Began, Part 1

NOTES FROM ABOVE GROUND

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

Introduction

“128. When it began, Los Angeles had no riverfront, harbor, or highway to somewhere else more important. Before Colonel de Neve opened his notebook and drew a plan showing house lots around a plaza and the church, Los Angeles had no explanation.” D. J. Waldie, Holy Land: a Suburban Memoir (St. Martin’s Griffin`1996).

Waldie’s misunderstandings about the birthplace of Los Angeles are common among those that think about it at all. Neve did not open a notebook and draw a plan. Before the Spanish pueblo of Los Angeles was founded in 1781, no one needed somewhere else more important to go to because the idea of somewhere else more important would have been incomprehensible to anyone living in the region, except possibly the padres of the two missions, but the padres were dedicated to conversions of the native people to Catholicism.

Los Angeles began as far as we now know in a large native village that was near, perhaps partly under, where City Hall now stands and extended to today’s Fletcher Bowron Square.

Felipe de Neve was governor of the Californias when he organized the founding of the Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles in 1781, although it is true that he earned the rank of colonel in 1774.

José Darío Argüello (1753-1828) drew a map in 1786 of the pueblo as it was five years after its founding.. https://www.kcet.org/lost-la/the-first-map-of-los-angeles-may-be-older-than-you-think. (Retrieved 6/17/2016). This link takes you to the map translated into English. https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/happy-birthday-los-angeles-but-is-the-story-of-the-citys-founding-a-myth. (Retrieved 6/17/2016) Under Neve’s orders, Argüello had led the first ten Los Angeles pobladores to the site of the pueblo that grew into Los Angeles in June 1781.

There was no church on Argüello’s map. The church would not be built until the pueblo had moved several times and its cornerstone not laid until 1817, so it wasn’t on the 1786 map.

Neve’s Reglamento (1780) described with words what each settler was to receive – building lots and field allotments surrounded by pasture, ownership rights (Feudal rights: the properties could not be sold.), even how many shoes a settler could have. There was no plan with images of house lots around a plaza in the Reglamento.

Los Angeles had a riverfront when it began. A riverfront is the land or area along a river. Indian people in the lived near the Los Angeles River, during all of its many changes in riverbed including when the Los Angeles River became the same as the San Gabriel River for a long time. The Indians did not need a harbor. They put their reed and plank boats into the ocean waves and paddled out to the Channel Islands with swordfish leaping around them and porpoises grinning ear-to-ear.

A highway is a main road, especially one connecting major towns or cities. Los Angeles had highways before 1780 that went to the Mohave people on the east, and a highway that went west past UCLA to Pacific Palisades where Ronald Reagan would one day live in an all electric house given to him by General Electric not all the far from the house of author Henry Miller. Los Angeles had two highways to the San Fernando Valley, and a highway through the Tehachapi Mountains to the Oakland Estuary. This network of highways became El Camino Viejo and El Camino Real. The nexus of the highways from San Diego to Oakland was Yang-Na.

If there is a mystery about where the Indian village stood in 1781, it is why the written history that we have about its location is confusing. One reason for the confusion is that the location of the Indian village is that the pueblo moved several times.

In the early years of the original pueblo, located near the mouth of what would be called “the Zanja Madre,” close to where the Broadway Bridge crosses the river, the native people and the pobladores maintained a collaborative relationship. Yang-Na was still then at a distance of less than two miles from the pueblo.

In about 1792, eleven years after the Spanish government founded the pueblo, it moved to a second location, probably southeast of where Union Station stands. This location was also about 2 miles from Yang-Na. The river flooded the second pueblo and destroyed its buildings in the winter of 1814-1815.

The third pueblo and its plaza, referred to as “the Old Pueblo” and the “Old Plaza.” The Catholic church laid the cornerstone for a parish church at the bottom of the Old Pueblo, on an eastern corner. The pueblo then moved to its next location in 1818.

The present plaza, and the area called “the birthplace of Los Angeles,” existed as a pueblo under Spanish, and then under Mexican, law from about 1818 to 1835, when the Mexican government declared it was a city. The parish church, popularly called “La Placita,” was complete in 1822.

In 1835, the city council – the ayuntamiento – removed the native people living in Yang-Na to a location a little to the southeast of today’s Union Station and established the Rancheria de los Poblanos and required the Indians to elect an alcalde — a mayor. After about ten years, the ayuntamiento relocated the native people again, this time across the river from Rancheria de los Poblanos to found El Pueblito, which lasted two years.

The San Gabriel Mission’s greatest number of neophytes was 1701, reached in the year 1817.

In 1834, the San Gabriel Mission and the San Fernando Mission lands were secularized, a change opposed both by the mission padres and by the more conservative members of the pueblo. These lands had been extensive, and all had been built and cultivated by Indians. Yang-Na had continued for as long as it did because the native labor force was critical for those that owned the ranchos – and who often lived in the pueblo much of the year – and for the work done in the pueblo itself. Some of the former neophytes moved to Yang-Na to work in the pueblo.

Some of the remaining people of Yang-Na moved to other rancherias or to the mountains. Some found work in the vineyards and orchards owned by European and United States emigrants to Los Angeles.

Pio Pico, Antonio Coronel, and Don Benito (Benjamin) Wilson sympathized with the plight of the native workers and relied on them for cheap labor. Pio Pico was himself partly of Indian and African descent. Coronel advocated on behalf of the Mission Indians. Hugo Reid, from Scotland, acquired his vast landholdings through his wife Victoria, who had been an assistant key keeper at the San Gabriel Mission. Abel Stearns (“Horseface”) acquired vast lands in Southern California that had been native lands.

Some of the natives that could not find work were sold at auction. In 1850, the American state legislature passed a statute that allowed the enslavement of Indians.

Another reason for the confusion about the location of Yang-Na in later years is that the Indians were both necessary and despised.

The original pobladores were mostly dark people. Luis Quintero and Antonio Mesa’s ancestors were African. Quintero’s wife Maria Petra Rubio was Mulatta, Pablo Rodriguez was Indian, and so was his wife. Alejandro Rosas and his wife were Indian. Jose Maria Vanegas and his wife were Indian. Jose Navarro was Mestizo and his wife was Mulatta. Manuel Camero was Mulatto, and his wife was Mulatta. Jose Fernando de Velasco y Lara was a Spaniard, but his wife was Indian. Jose Navarro was Mestizo. His wife was Mulatta.

Later emigrants to the pueblo, like Coronel and the United States and European settlers, were white.

Those that employed native labor became the “Californios” and they were gente de razón – “people of reason,” or Hispanicized settlers. Pursuant to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ceded Mexican lands to the United States, former citizens of Mexico, or gente de razón, were by definition “white.”

After California became a state, former residents of the southern states in the United States moved to Los Angeles, and, within a short time, the gente de razón became grouped together as “Mexicans.” When Lincoln was assassinated, one new resident of Los Angeles went berserk with joy at hearing the news.

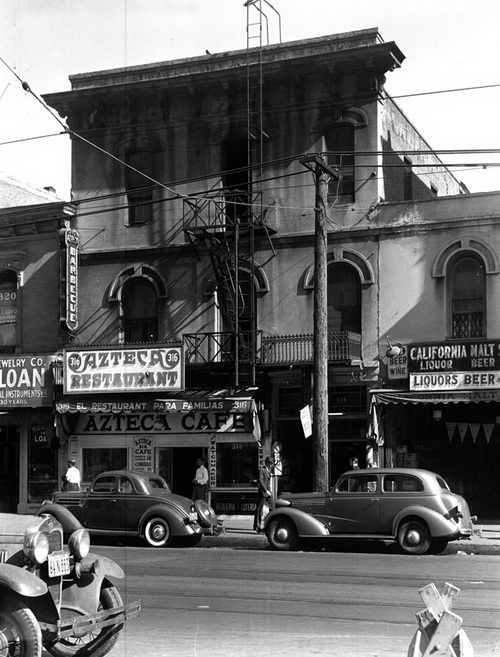

The “Mexicans,” and emigrants from Sonora during the Gold Rush, moved to an area a little north of the pueblo to what became Sonora Town, the first barrio in Los Angeles. Adobe houses from the Mexican era stood in places in Sonora Town even after it became New Chinatown.

The Americans later confabulated a faux and self-contradictory history that masked the importance of the native people to L.A.’s history.

California’s seminal historian H. H. Bancroft, California’s relied on testimonies taken by two interviewers. Antonio Coronel was one of the witnesses to L.A.’s past. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1834. Coronel knew where Yang Na had been, but so far I found no statements by Coronel about the location of the Indian village.

Hugo Reid knew where Yang Na was. His in-laws had lived in it. The legend of Victoria Reid is that her parents were among the ruling elite. He arrived in Los Angeles in 1832, when Yang-Na still stood where it had been back in 1769, when the first Spanish explorers arrived, minus the hunting and gathering territory it once had. He wrote a series of 22 letters, published in 1852 – after the city’s leadership relocated the people of Yang-Na twice – about the Indians. The letters provide an important ethnographic portrait of the native people but Reid did not write about where the village had once stood.

This is a city full of myths. Hollywood makes them, although none of them so far are about the people that lived here first, except the film about real Indians played by real Indians living on Bunker Hill in 1960, when Bunker Hill was a run down neighborhood of decaying Victorian-era mansions and low rent tenements: The Exiles (1961), but it’s not about the people that lived in Los Angeles first, the ones that lived in the plateau near the river in the village of Yang-Na.

Yang-Na: the beginning of L.A.

People sometimes remember Indians lived in LA before the Spanish explorers passed through when road or real estate excavations uncover native remains or artifacts. In 2011, excavation of what will be the outdoor space of La Plaza de Cultura y Artes downtown near Olvera street unearthed the bones of the first settlers of Los Angeles – Native Americans, Spanish, Mexican and European people and their intermarried descendants.

Native people, probably Chumash, lived in Los Angeles County for from 2,500 years ago to 9,000 years ago in the wetlands area near Ballona Creek. http://westerndigs.org/history-of-ancient-los-angeles-was-driven-by-its-wetlands-8000-year-survey-finds/. A later people merged with or supplanted them about 2,000 years ago, arriving from the Mojave. Archeologists excavating a housing development site found a milling site 8,000 years old 30 miles east of downtown Los Angeles. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/tech/science/discoveries/2006-03-03-prehistoric-mill_x.htm. In 1914, remains of a woman were found in La Brea Rancho. 2009 carbon dating shows them to be 10,000 years old. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2009/11/the-skeleton-that-the-page-museum-doesnt-want-you-to-see.html. (These sites were all retrieved 6/14/2016).

The native people that lived in Los Angeles are today sometimes called the Tongva. Some descendants prefer the name Kizh. The Spanish missionaries that founded the Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, founded in 1771, called the people that lived in Los Angeles and on those Channel Islands called San Nicolas, Santa Barbara, Santa Catalina by the name Gabrieliño or Gabrieleño, which the Americans wrote as Gabrielino. The Spanish called the Tongva people that lived in the San Fernando Valley Fernandeño because of their association with Mission San Fernando Rey de España, founded in 1797.

The Tongva people populated a territory covering almost 4,000 miles, including the island villages, Orange County, and most of Los Angeles County.

Kent G. Lightfoot and Otis Parrish, California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction (University of California Press 2009):

“We have good evidence that in some times and places Native peoples experienced poor health and hardships brought about by periodic food shortages, parasites, endemic diseases, violence, warfare and political manipulations.” The periods of greatest violence coincided with periods of resource depletion and resource depletion coincided with extended droughts, one of which lasted 43 years.

The people living in the big trading village that became Los Angeles referred to themselves with a word in their language that meant river. The village itself was by some called Yang-Na, or yaanga and by others as Yabit.

McCawley found evidence of another large village in the area: “’Veberovit’ as ‘en la Rancheria inmediata al Pueblo Los Angeles.’” Mission San Gabriel converted 31 converts from “Geverobit” between 1788 and 1809, which suggests a modestly sized village, recruitment problems, or that the settlers from Mexico needed the Indians’ labor too much to let them leave to live at the Mission.

Yang-Na probably had all the problems of any big village with a lot of people living in it: increased susceptibility to illness, a less than egalitarian hierarchy of elite niches, sewage disposal. Its people were not living up in the mountains throwing spears at bears. Some of the closely woven conical homes housed up to fifty people, and big villages had at least 400 people living in them. Yang-Na was a very big village.

William McCawley, The First Angelinos: The Gabrielino Indians of Los Angeles County (Malki Museum Press, Morongo Indian Reservation 1996):

“Inland communities maintained permanent geographical territories or usage areas which, according to studies of the inland Luiseno, probably averaged 30 square mines….these territories are sometimes referred to by the Spanish term Rancheria. … Within its territory, or Rancheria, each community maintained a primary settlement as well as a variety of hunting and gathering areas, ritual sites, and other special use locations. These subsidiary sites might be periodically occupied while a special activity, such as acorn gathering, was under way; once that activity was completed the population would return to the main settlement.” Later, “Adjacent to the settlements were large cleared areas which were used as playing fields for races and games. Sweat huts were commonly located near streams or pools of water which were used for rinsing, while the special huts occupied by women during menstruation were located near the outskirts of the settlement….The center of each community was occupied by an unroofed sacred enclosure known as the yovaar…” The fence was formed of short stakes and intertwined willow branches that reached eight feet high. The enclosure was about fifty feet in diameter.

The yovaar seems to have been the spatial equivalent of the plaza in the Spanish colonial pueblo. What they did in the yovaar was not the equivalent of the plaza:

Lightfoot and Parrish:

“The Chinigchinich cult, involving the ingestion of the toloache plant (Datura wrightii), also called jimsonweed, played a particularly important role among Tongva and Luiseno communities in early historic times, as observed by Spanish explorers and missionaries. The drug produced hallucinations and visions among participants, and it was widely used in the initiation rites of young boys and girls, as well as the initiation rites of new members into the Chinigchinich cult. Various ceremonies centering around the Chinigchinich cult typically involved the construction of a shrine or alter, which might include various offerings, such as feather, coyote skins, arrows, and the remains of raptors. In front of the shrine, one or more participants created one or more intricate, colorful sand paintings depicting various aspects of the universe. The participants destroyed the paintings at the end of the ceremony.”

Gabrielino houses ranged from 12 to 50 feet in diameter. The floor plan, before missionization, was circular. The roof was dome-shaped. They were tightly woven of reeds and willows and “proof against rain and were warm and comfortable.” A trench caught runoff that might enter during a storm. Tule mats covered the reed floor. The Indians used rugs and blankets of rabbit, bear and sea-otter hides.

See: http://www.tongvapeople.org/?page_id=696. (Retrieved 6/12/16).

The primary area of a village, then, would be perhaps 4,000 feet in diameter, not including the large cleared areas.. Hunting and gathering areas surrounded it, making the territory of a village quite large.

The location of Yang-Na was near City Hall.

American historians that wrote the first Spanish pueblo was adjacent to Yaanga or Yang-Na (or Yabit), could have meant the community of homes in the football field sized area, or they could have meant an area perhaps the size of the Los Angeles Arboretum and Botanical Garden. To the 18th century Indian mind, Yang-Na would have been the larger area. To the Spanish and then Mexican and then American mind, Yaanga would have translated to the smaller area because that size would have corresponded to their ideas of a village.

The village was located in an area near water but high enough to avoid damage by flooding. “(P)ermanent communities,” according to McCawley’s research, “typically developed near the interfaces of several environmental zones or interfaces.” Location near different environmental zones allowed the native people to reach plants and animals that might be depleted in one zone but thriving in another.

McCawley, in The First Angelinos, states the exact location of Yang-Na, the “Indian precursor” to the city of Los Angeles is uncertain. “The original community was abandoned sometime prior to 1836….and was succeeded by a series of later rancherias inhabited by Gabrielino and other Indian refugees.” McCawley places, nonetheless, the 1769 location at around City Hall.

McCawley’s description of location of the village could not have included the extensive areas needed for basket-making, boat-making, playing fields, and for hunting and gathering, which he elsewhere describes.

No one abandoned Yang-Na. His use of the word “abandoned” suggests that one day the native people voluntarily moved to other rancherias some with Gabrielino and some with other Indian refugees.

Actually, the Mexican-era city council took the property. There was no legal impediment to its doing so. There was no treaty. There was up to then probably no survey of Los Angeles. Land titles, the way we think of them today, did not exist. No one recorded deeds but the Indians did not have deeds.

In 1785, under the authority of the Spanish government, each pueblo became entitled to own “the extent of four leagues in a square.” What that precisely meant was unclear but the pueblo owned a large amount of land, and Yang-Na was within whatever was meant by “four leagues in a square.” Antonio Coronel, Juan Sepulveda, and Cristobal Aguilar may have surveyed municipally owned lands in 1834, starting from La Placita. If there was such a survey, it is lost.

The council then moved the former community of Yang-Na and moved them all to another location. After a few years, the city council allowed a vineyard or vineyards to be build on the second village site and relocated the native people again to the east side of the river.

One suggestion for the pre-1781 site of Yang-Na is the area surrounding El Aliso, after which Aliso Street is named.

In an 1870 photograph of the plaza area, a giant sycamore looms: El Aliso. http://waterandpower.org/museum/Early_Plaza_of_LA_(Page_1).html.

El Aliso, although a significant landmark for the native people all over Southern California, was not the site of Yang-Na when the Spanish explorers arrived and not the site of Yang-Na during the years the pioneers from Mexico lived in L.A.

A 1860s photograph at the Braun Research Library Collection at the Autry museum shows rather more clearly the dominating mass of El Aliso to the south, perhaps about where the train tracks behind Union Station now travel.

Once part of a riparian forest, El Aliso was about 400 years old at the time it was cut down in 1892. The village of Yang-Na most likely existed before El Aliso was a sapling. So, although El Aliso comes up occasionally in references to Yang-Na, it was not the site of the village during the time eight Tongva men walked from it to meet Father Crespi in 1769; it was not the site of the village when the 44 pioneer settlers walked from their camp near the San Gabriel Mission in 1781: it was not the site the Mexican-era city chose to relocate the native people involuntarily in 1835; and it was not the site the city chose to relocate the villagers during the beginning of the American occupation in 1847.

The people of Yang-Na helped the first settlers build the first pueblo and the irrigation system during the Spanish era

Oakland Museum historian Louise Pubols writes an explanation of early interactions between the pobladores and the native people and the 1835-1836 relocation of Yang-Na in “Born Global: From Pueblo to Statehood,” in a collection of essays about Los Angeles, with an introduction by William Deverell and Greg Hise, in A Companion to Los Angeles (Wiley-Blackwell 2010).

Dr. Pubols writes:

“Yaagna men constructed and maintained the zanja system, built adobe houses and public buildings, and tended horses and cattle. Yaagna women ground corn and prepared food, washed clothing, weeded gardens, and hauled water and wood. Both cultivated and harvested corn, beans and melons. In exchange, settlers made no demands that they convert to Christianity, allowed them freedom of movement, and gave them one-third to one-half of the harvest, or paid them in manufactured items such as cotton cloth, glass beads, knives and hatchets. Native people might also acquire these goods in exchange for baskets, clay and soapstone bows, rabbit blankets, or tanned deer, seal and sea other pelts…”

Pubols may be imprecise about who built the zanja system. Other sources indicate the settlers’ children, some of them quite young, built the brush, stick and mud toma that impounded the river water for the zanja, or irrigation ditch, and that the settlers from Mexico dug the first zanja.

Also, the Indians helped the original settlers build the first homes, which were huts built of brush and willow sticks. Most sources concur the settlers lived in the brush huts for two years before building adobe houses. One source indicates the pobladores in the two successful pueblos – Los Angeles and San Jose — lived in brush huts until the founding of the Pueblo de Branciforte, near Santa Cruz (1797); that is, for sixteen years.

Pubols continues: “Settlers and Indians danced, gambled and attended fiestas together, and sometimes formed casual unions. But other settlers, more formally, sponsored Indian children in baptism and married Indian wives…”

Secularization of the missions caused changes in the relationships with the gente de razón and the native people

Pubols goes on to describe the changes to Yang-Na that resulted from the liberal movement of the gente de razón — mostly centered in Monterey, to break free of Mexico after Mexico became independent from Spain.

The Liberals obtained the secularization of the mission lands, which the conservative and mission factions opposed. “For Mexican liberals,” she writes, “secularization was a tool in the construction of a new Mexican nation. Not only would it break the power of the Church in civil affairs but also it would liberate both the Indians and the land of California. Former neophytes, along with other private citizens, could create family farms and ranches from the undeveloped tracts of mission land, and boost the national economy in the process…

“As the mission estates lost their blacksmiths, weavers, and carpenters, the town increased the number of urban craftsmen and artisans.”

“…(T) population in the town itself (of Indians) actually increased, from 2000 in 1820, to 553 (of 1,088) in 1836, and 650 (of 1,250) in 1844, as ex-neophytes flocked to Los Angeles in search of work, outnumbering the gentile population. George Harwood Phillips has studied the devastating effect this migration had on the political and economic power of the Indians of Yaagna. Unable to find enough work to support their increased numbers, the population became increasingly unable to negotiate the terms of their employment, and fell victim to economic exploitation.”

The Mexican-era city council moved the people of Yang-Na out of their village so the city could expand into the former village

In 1835, the ayuntamiento – the governing council of the tiny Mexican city of Los Angeles – moved the native people that remained in that village, and including those Tongva that had been freed from their ties to the missions, to municipally owned land closer to the river, a little south of Union Station somewhere between the vicinity of where the Twin Towers Correctional Facility now stands to the 101 where it crosses the river and merges into the San Bernardino Freeway. Google maps show Yang-Na at that location. The city’s name for the relocation site was Rancheria de Poblanos.

The relocation site was also not in the area of El Aliso.

El Aliso stood in the courtyard of the Vignes Winery by 1830. The Vignes Winery was composed of 100 acres in the area now bound by Aliso Street and Alameda, east of Little Tokyo. Yang-Na, after its people moved from their earlier permanent location, could not have been moved to the purported location of El Aliso in 1835, because the Vignes vineyard encompassed that area down to Seventh Street.

The first commercial citrus acreage in the state (The first orange and lemon groves in California was planted at the Mission San Gabriel in 1804.) was planted when William Wolfskill planted the seeds he got from the mission in 1840, encompassing 165 acres bounded by North Alameda and East Ninth. The main entrance of the Wolfskill orchard was at 239 North Alameda.

That orchard was a little south of where El Aliso stood, and it is south of where Pubols states the relocated Yang-Na stood. The orchard’s location indicates that part of the outskirts of Los Angeles had become valuable land by 1835.

Moreover, from the 1860s photograph that showed the giant sycamore, the tree stood close to the river and to the west of Union Station. Rancheria de Poblanos had to have been between Twin Towers and Cesar Chavez Boulevard, most likely along North Vignes Street, inasmuch as the tree stood in the Vignes courtyard.

The village of Yang-Na included the area where City Hall stands

For those who lived in what would become L.A. before the summer of 1781, the natural big landmarks were the ancient roads, the river — although it changed shape and sometimes changed course altogether – the San Gabriel Mountains, the Santa Monica Mountain range with its tit-like bump above the river and its coccyx in the sharp hill above Elysian Park, the tar pits, the stump-filled Arroyo Seco, El Aliso – the remaining 400 year old sycamore — and the ocean. The smaller geographic landmarks of unusual rocks, or particular rocks, or historic river changes are for now lost to us.

There were low hills – a tip of one showed behind a building in a 19th century photograph and Hill Street once traversed a hill – and the big hills that became known as Fort Moore Hill, Bunker Hill, and Pound Cake Hill. Pound Cake Hill now accommodates the Stanley Mosk Courthouse. You enter the first floor of the Courthouse on Hill Street and emerge on the fourth on Grand. We can no longer see the “pound cake” shape. Fort Moore Hill and Bunker Hill both have been considerably lowered.

The National Park Service consensus, based on the research by U.C. Berkeley Professor Herbert E. Bolton (1870-1953) is that the Portolá expedition (1769, comprised of 63 men on horseback and pack mules) crossed the river on their way from the San Gabriel River at a saddle in the hills in the Elysian Valley (Frogtown). http://www.anzahistorictrail.org/blog/post/48. Fr. Crespi’s diary entry mentions the Arroyo Seco, which enters the river near Figueroa, at the bottom end of Frogtown.

Spain had several definitions of league. A Spanish colonial league was roughly the distance traveled on horseback in an hour, officially 2.5 miles after 1536. (Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold, Compilation of Colonial Spanish Terms and Document Related Phrases. (SHHR Press, 1998).

A City of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering history computes a “league” during the Mexican-era Los Angeles (Beginning in 1821) as 2.63 miles.

Miguel Costansó (1741–1814), original name Miquel Constançó, accompanied the Portolá expedition. He was an engineer, cartographer and astronomer. Crespi may have relied on Costansó’s calculations to determine distance. Crespi’s description, however, does not entirely make sense if they did cross the river at the Broadway Bridge. If they went west – as he wrote that they did — they would have had to climb through what is now Elysian Park. Indian main roads that became El Camino Viejo, which Portolá followed, did not climb those hills.

Crespi wrote they marched west:

“After one-half league’s march, we approached the Rancheria of this locality.”

The Spanish referred to Indian villages as Rancherias. By “Rancheria,” Crespi would have meant the woven huts surrounding the yovaar. Crespi was born in Majorca in 1721 – the same island where Father Serra had been born in 1713 — arriving in New Spain in 1749, probably leaving from Cadiz, well into middle age when he first saw Yang-Na. Crespi would have understood “village” as Serra would have; that is, a collection of homes surrounded by agricultural fields.

Steven Hackel’s biography of Father Serra describes Majorca as mostly owned by a few rich families and worked by those who leased it or worked as day laborers during Serra’s youth. Illiteracy was common. Most people in Petra, Serra’s village, lived in agricultural flatlands surrounding the town, working as hired hands.

Crespi wrote the expedition went west over good pasturing land, which means they did not climb hills and so could not have traveled directly west.

Traveling southwest, through the area informally called The Cornfields, now the Los Angeles State Historic Park 1.25 miles – roughly 8,000 feet. If they started at the Broadway Bridge and went 1.25 south, they would have been around today’s Third Street. If they had gone southwest, perhaps somewhere around Disney Hall; inasmuch as Disney Hall is on a hill, which used to be an even steeper hill than it is now, then they most likely encountered what they perceived as the Rancheria at around City Hall.

W.W. Robinson, in Los Angeles from the Days of the Pueblo (1981 The California Historical Society), places the village of Yang-Na “in the area of the present City Hall and perhaps on the site of the pioneer hotel, the Bella Union.” Robinson was a professional title searcher but he bases this conclusion on the work of previous historians.

This location corresponds to the nexus of El Camino Viejo in downtown Los Angles indicated in the Ord survey, discussed in the chapter of this book on El Camino Viejo. The map is available online through the Los Angeles Public Library website.

In 1849, Edward Ord surveyed what is today downtown in his “Plan de la Ciudad de Los Angeles.” The Ord survey showed streets, drainage, vineyards, gardens, and churches. The city part was narrow and small. Through it ran the ditch called the zanja that brought water from the river. The area to the west was comprised of fields, as with the area south of where Union Station stands. Those portions within the land still owned by the city were mostly to the west to where Pershing Square is and north of farms. Ord squared those into a grid for sale by the city to raise money for municipal purposes. The planned grid went as far to the north as the hills that surrounded the city: the steep hills now called Elysian Park, the somewhat less steep hills of that would be called Fort Moore and Bunker Hill, and further along, the hills that would be called Angelino Heights, Echo Park, and the hills south of Sunset in today’s Silver Lake District.

The branches of El Camino Viejo in the Ord survey met at a location around City Hall.

Over the years since the American occupation of Los Angeles, the site of Yang-Na has been described as “near” the pueblo, “adjacent to the pueblo,” and that the pueblo was built “right on top” of Yang-Na. Americans, like the Spanish, would have understood Yang-Na to be the collection of homes around the open space fenced with brush. For the native people living in Yang-Na, all of what is now downtown to the river on the east, perhaps to Fern Dell on the northwest, south as far at least to the 101 Freeway, would have been Yang-Na.

In the 1820s, an adobe home stood at what is the site current City Hall, which indicates either that the Spanish-era and the Mexican-era gente de razón had begun building in the central village area, or that a Tongva resident of the village built an adobe house.

In August 1853, John Temple sold the lot to the City and to Los Angeles County.

By 1820, three years after the plaza moved to its present location, and 39 years after the founding of the pueblo – wherever the pueblo first stood — therefore, the native people inhabited a much smaller area than they had in 1769.

Part of the village part of Yang-Na stood at the location of the Bella Union Hotel, at about where the Triforium stands.

In 1835, “three American trappers” – William Wolfskill, Joseph Paulding and Richard Laughlin – built a one-story adobe on the east side of Commercial Street, one block east of Main Street as a home for Isaac Williams, a New England merchant who arrived in Los Angeles in 1832. The location is the Fletcher Bowron Square, 300 block of North Main, between Temple and Aliso Streets.

Pio Pico bought the adobe to use as an office in 1845 when he first became governor of California. Still a one-story structure, it became for a short time the capitol building of Alta California. By 1851, it had become the Bella Union Hotel, when a second story was added. A third story was added in 1869.

California Historical Landmark 656 on the 300 block of North Main Street states, “Near this spot stood the Bella Union Hotel, long a social and political center. Here, on October 7, 1858, the first Butterfield Overland Mail stage from the east arrived after leaving St. Louis. Warren Hall was the driver, and Waterman Ormsby, a reporter, the only passenger.”

Governor of Alta California, pursuant to his power under the Spanish government granted Juan Jose Dominguez the San Pedro grant in 1784 (48,000 acres). He also granted Manuel Nieto “Los Nietos” in 1784 (167,000 acres) and the San Rafael grant to José María Verdugo in 1784 (36,400 acres). In 1787, he granted Jose Vicente Feliz the Rancho Los Feliz (6,647 acres). Antonio Maria Lugo acquired Rancho San Antonio – today’s Bell, Bell Gardens, Maywood, Huntington Park, Vernon, Cudahy, South Gate, Lynwood and Commerce – in 1810. This is a partial list.

The grants initially were not owned by the grantees; rather, Spanish law dictated that the Spanish government owned the land and the grantees obtained the use of them. If the land was not developed, the land reverted to the king of Spain. Some grantees lost their rights to the land because they could not prove they used the land. After Mexico gained its independence from Spain, and after the secularization of the missions, grants had to be approved by the governor and the legislature. Once they were approved, however, they were no longer usufruct ownership and became closer to the English – and American – idea of private property. The three Spanish pueblos – first, San Jose, and then Los Angeles, and for a brief time Branciforte (now part of Santa Cruz) – owned lands dominated by the principal that pueblos owned four leagues square surrounding each pueblo.

By 1835, enormous ranchos surrounded the pueblo, largely given over to cattle ranching. These were all heavily dependent on Tongva labor. The pueblo, or municipal lands, remained undeveloped until the American government’s occupation after 1850. The idea behind municipal ownership was to prevent speculation. The American governments subdivided the land and either sold at auction or gave it away. American water ownership rights – a hybrid legal system, partly based on riparian ownership rights — led to a further diminution of the legacy of municipal ownership, although the city later successfully challenged these rights in court. Owners of land on water’s riparian rights, derived from English law, depleted the aquifers and exhausted the artesian springs.

The ideal of private ownership of land was an English law development that began as a result of the Crusades, which, along with economic changes, contributed to the writing of the Magna Carta, a charter between King John of England and the barons. The myth of the liberties expressed in the Magna Carta contributed to the various Enclosure Acts, which reduced commonly owned lands, and to a series of laws that contributed to the English idea, later reflected in the American Constitution’s Fifth Amendment, that the private ownership of property was the bulwark against tyranny.

The long English and then American tradition of private ownership of land was a given by the time of the American occupation of California, and contrasted with the Spanish ideas about ownership tempered by social constraints. It reached its most extreme form in California, but the primary reason for the American sale and sometimes gifts of municipal land was to raise taxes.

Peter Reich, “Dismantling the Pueblo: Hispanic Municipal Land Rights in California 1850, The American Journal of Legal History, October 2001, Volume XLV, Number 4:

“The commodification of American town commons had the effect of loosening town governments’ ability to control land uses, and thus their economic, political and social authority. Early nineteenth century Americans assumed, in the words of legal historian William Hurst that as land became a trade-able commodity ‘the normal destination of the public domain should rest in private hands.’”

Professor Reich contrasts the American view with the colonial Spanish view:

“The pueblo’s form derived from Spanish Renaissance planning traditions, which allocated conveniently located space for the benefit of the community, intermixed with a variety of residential and agricultural lots. Towns in the north of New Spain and Mexico were usually laid out around a central plaza faced by official and church buildings, with surrounding lots distributed to the colonists, and private fields, common lands, and other municipal property placed on the fringes.”

The native people in California did not fit within either system. They had no idea of private ownership before 1781.

The Indians became laborers, first for the missions and later for the pueblos and the ranchos, although some escaped. These were “fugitives.”

McCawley:

“The community of Yaanga survived until 1830 or 1836, although in later years it may have resembled a refugee camp more than a community. Yaanga was ‘adjacent to’ the pueblo of Los Angeles. Indians from Yaanga supplied the pueblo with cheap labor as well as many of the material goods used by settlers. This interdependency undoubtedly helped Yaanga to survive longer than most other Gabrielino communities.”

W.W. Robinson, in “The Indians of Los Angeles: As Revealed by City Archives,” The Quarterly: Historical Society of Southern California, Vol. 20, No. 4 (December 1938), pp. 156-172): “Its existence (The Indian encampment around and south of El Aliso after about 1836, the Rancheria de Poblanos) gave rise to the later fiction that it was the original Yang-Na.”

The ayuntamiento moved the people living in the Rancheria de Poblanos across the river to found the community called “El Pueblito” so that Johan Groningen could establish a vineyard.

W.W. Robinson found that, in 1838, Juan Domingo moved onto the Rancheria de Poblanos and started to cultivate a vineyard. The City fined Domingo.

W. W. Robinson in copying the official documents did not note that Juan Domingo’s birth name was Johan Groningen. Groningen was a carpenter on the Danube, which sank in San Pedro harbor. Groningen swam to shore and decided to stay.

From An Illustrated History of Southern California (The Lewis Publishing Company, 1890), page 754, “He (“Juan Domingo”) planted a vineyard, married Miss Felis, planted a vineyard on Alameda Street, and lived there until he died, December 18, 1859, leaving a large family and many friends.” This book is available free on-line at: https://archive.org/stream/illustratedhistofsc00lewi#page/754/mode/2up.

The obituary of Reymunda Feliz de Romero – the wife of “Juan Domingo” — in the Los Angeles Times on February 26, 1908, reports she was born in Los Angeles in 1809. Her father was Juan Feliz, who owned the Los Feliz Rancho, a part of which was then – and is now – Griffith Park. Her mother was Maria Ignacio Verdugo, owner of the Verdugo Rancho. According to the obituary, the old Feliz homestead, where Senora Romero was born, was on Aliso Street near “what is now Lyon Street.” That location was the location of the Rancheria de Poblanos.

This was not the old Feliz homestead. Homestead in English means just property, with sub-meanings of a house, maybe a farmstead, from the word “toft,” meaning the site for a dwelling. The Feliz family’s rancho was enormous. It was bounded on the east by the Los Angeles River, included Griffith Park and the Hollywood Hills almost to today’s Universal Studios, and includes today’s Los Feliz district to about Vermont and Prospect and part of the Silver Lake district. Romero’s ancestor Jose Vicente Feliz – a soldier with the Anza expedition and Comisionado of the Los Angeles Pueblo – received the grant for Rancho Los Feliz in 1795. Maugana was the site of the Tongva Rancheria preceding the grant. Maugana was located in what is now Hollywood. The Feliz adobe was built in the 1830s, and it still stands in Griffith Park (Park Ranger’s Headquarters.) Most of the rancheros lived in the pueblo in the early years. Romero, born in 1809, may have been born in an adobe house in the pueblo, and she may have returned to what had been the pueblo when she died.

After Juan Feliz died, Maria Ygnacia Verdugo claimed her late husband’s property, the Feliz Rancho. She then married Juan Diego Verdugo but continued to occupy Rancho Los Feliz. In 1853, she deeded a portion of the rancho to her daughters.

According to Mike Eberts in Griffith Park: A Centennial History (The Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 1996), the daughters sold their portion for $1 an acre. Maria Ygancia Verdugo deeded the remainder to her son Antonio. The “Indian retainers” were probably not the Indians Romero’s husband had relocated but her employees, the ones that did the work on her vineyard. Mrs. Jose Dolores Sepulveda, born in 1840, was Juan Domingo’s only surviving daughter in 1908, when her mother died. Jose was one of the sons of Francisco Sepulveda, grantee of San Vicente y Santa Monica grant in 1839. Sepulveda Canyon is named after Francisco Sepulveda. There is no Ogler Street in Los Angeles. The Sepulveda House, built in 1887 by Eloisa Martinez de Sepulveda, is between Olvera Street and Main Street.

Senora Romero was not born on Aliso Street near Lyon Street. This was the vineyard property Groningen/Domingo attempted first to just take from the native people that had been moved to the area. The City Council fined him, and then he petitioned to have the Indians removed to the other side of the river and he paid the City $200 for the land.

The records W.W. Robinson located show that in July 1839, Groningen’s (Domingo’s) neighbor Luis Vignes said he was taking Rancheria de Poblanos to increase his vineyard. The ayuntamiento told him he couldn’t do that.

In 1845 Juan Domingo asked that the Indians be removed from the land near the Vignes orchards. In the same year, the council decided that the Indians could not attend the church for mass because they were dirty and other people would get dirty clothes from sitting near them. In June 1845, the Police Commission recommended removing the Indians but washerwomen would be allowed to use the zanja for washing clothes. In December, the city moved the Indians across the river and gave the land below El Aliso to Juan Domingo and Raymond Feliz.

In December 1845, Juan Domingo bought the land that had been the Rancheria de Poblanos for $200, supported in his effort by Pio Pico, who needed $200 for a trip he needed to make.

The Romero obituary stated that the 25 acres of that property “embraced more than 25 acres and the establishment was one of the most lordly in the pueblo. The buildings were all of adobe, the main house being a rambling affair with patio and wide verandas. Surrounding it were the houses of the Indian retainers…”

Senora Feliz de Romero lived at the vineyard property her husband bought from ayuntamiento until she became quite old and moved to her daughter’s house, Mrs. Louisa Domingo de Sepulveda at 307 Ogler. Casa de Don Dolores Sepulveda was located three blocks south of Bundy. Dolores was one of the sons of Francisco Sepulveda, grantee of the rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica. He had trouble getting his title cleared and died when he was shot with an arrow on his return trip from Monterey. By 1908, his wife would have been living somewhere else. I find no “Ogler Street.” The Sepulveda House, however, located on Olvera Street, built by Anastacia Sepulveda, still stands. Anastacia built the house as a boarding house.

Juan Domingo’s wife lived almost 100 years. Her family’s wealth grew from land where Tongva people had lived for at least 13,000 years. She not only frequently saw native people in her daily life, she became their employer. She was alive when Mexico won its independence from Spain. The creeks that ran from her family’s hills watered the meadows between the Silver Lake hills.

Her Dutch-born husband subdivided the southern end of the former Feliz rancho: the Los Feliz district, Los Feliz Boulevard to the river, the Silver Lake District to about the middle of the reservoir (presently a big hole in the ground), creating the first farms in that part of Los Angeles, farms that in reality continued to exist in spite of the 1886 subdivision map that gave Scotch names to the streets.

The Autry’s Collections online reveals a survey of the southern boundary of the Los Feliz Rancho. “Nellie M. Bustillos and Family, descendants of Don Jose Dolores Sepulveda” donated the survey. That is, descendants of the Dutch sailor that swam ashore to San Pedro and had the influence to have the native people thrown off land he wanted to cultivate as a vineyard, and one owner of a portion of the Feliz Rancho, Senora Romera. The Los Feliz Rancho’s southern boundary was land owned by the City of Los Angeles, which included part of the Silver Lake reservoir. http://collections.theautry.org/mwebcgi/mweb.exe?request=image;hex=98_91_2.jpg;link=173198, Some of the water that fed the Silver Lake reservoir came from land and water rights owned by Senora Verdugo in 1852.

The survey’s date is December 22, 1856. Mr. Juan Domingo – the same Dutch sailor – commissioned the survey. If he succeeded in subdividing the property and selling it, the purchasers created smaller ranches and farms up to the boundary with the municipality. In 1886, during the “Rose Dawn” after the railroad reached Los Angeles, developers created two “paper towns,” that is, towns created by subdivision maps that were fictional. Two of those paper towns that had been created through subdivision maps within the 1856 survey were Ivanhoe and Kenilworth. The Ivanhoe subdivision became the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles after William Mulholland built the reservoir, which is presently a big dirt hole.

The city evicted the Indians living in El Pueblito after the American occupation

According to Pubols, basing her conclusion on W.W. Robinson’s Land in California (1938), in 1845, the city forced the residents of Rancheria de Poblanos to move across the river from the location that is now Commercial and Alameda Streets.

From an 1872 map on the Huntington Library digital website, “Old Aliso Road” crossed what was then several branches and marshes related to the Los Angeles River. The road crossed to the main highway to the San Gabriel Mission. http://hdl.huntington.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15150coll4/id/7475/rec/19.

El Pueblito, if it moved “across the river,” was located in an area that roughly corresponds to the area south of today’s Cesar Chavez Avenue and north of the San Bernardino Freeway.

The Mexican residents of Los Angeles put up on defense to the invasion by the combined forces of Commodore Stockton and Brigadier General Kearny, and John Fremont, Andres Pico (Pio Pico’s brother) and six others signed articles of capitulation in January 1847. The articles were informal; that is, the federal government was engaged in war against Mexico (1846-1848) and it the war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 2, 1848).

American soldiers garrisoned in Los Angeles following their military take over frequently gathered in Pueblito for sex and to drink brandy.

W.W. Robinson’s research found that on November 8, 1848, the city ordered the Indians to leave El Pueblito and razed the settlement. From then on, whoever employed the native people had to keep them on their premises and not let them off. If an Indian was self-employed, he had to stay outside of city limits and not to live with other Indians. If an Indian couldn’t find work within four days, then he was to be forced to work on public works.

In August 1850, the City Council decided Americans were to help with “the Indian problem.” The Indians were to be auctioned off to private people to work on fines for not finding work and for drunkenness. Inasmuch as the Americans paid the Indians with brandy, drunkenness after six days of heavy labor became a common occurrence.

That was the end of Yang-Na. The Tongva people, however, continue. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLITAq0aJinsQF6fvmXBmTLtdU5W6KWEbR. (Retrieved 6/12/16)

Yang-Na became L.A.’s civic center.

As what happened to the site of the village of Yang-Na:

John Temple built a city hall/market house that opened in 1859. It was located on Main, Spring, Market and Court Streets, a site south of Temple Street that is under today’s City Hall.

The first brick building, a small jail, was built behind this first city hall, enclosed behind a ten-foot fence built to keep vigilantes out. Condemned prisoners were hung on the gallows in the jail yard. The street behind the back of the fence was at first called “Jail Street” and later Franklin.

Horace Bell, a lawyer and the author of Reminiscences of A Ranger: Early Times in Southern California, wrote about the Bella Union:

“The house was a one-story flat-roofed adobe, with a corral in the rear, extending to Los Angeles Street with the usual great Spanish portal near which stood a little frame house, one room above and one below. The lower room had the sign “Imprenta” over the door fronting on Los Angeles Street, which meant that the Star was published therein. The room upstairs was used as a dormitory for the printers and the editors. . . On the north side . . . were numerous pigeon-holes, or dog-kennels. These were the rooms for the guests of the Bella Union. In rainy weather the primitive earthen floor was sometimes, and generally, rendered quite muddy the percolations from the roof above. . . . The rooms were not over 6×9 (feet) in size. Such were the ordinary dormitories of the hotel advertised as being the “best hotel south of San Francisco.” If a very aristocratic guest came along, a great sacrifice was made in his favor, and he was permitted to sleep on the little billiard table.(In the bar) during that time were the most bandit, cut-throat looking set (of people) that the writer had ever set his youthful eyes upon. . . . all . . . had slung to their rear the never-failing pair of Colts,generally with the accompaniment of the bowie knife.”

A parking lot replaced the Bella Union in 1940.

The Triforium, that six-story of colored glass public art (Installed 1975), now rises at the edge of the Fletcher Bowron Square at Temple and Main.

That location about where the Bella Union stood and, a short walk to where City Hall stands, is most likely the place where the largest trading village of native people stood at the time the Spanish soldier Gaspar de Portolá i Rovira led the first land expedition to what would become the City of Los Angeles in 1769, accompanied by Fr. Juan Crespi, the expedition’s prolific diarist.

In the early 1860s, a reservoir for water from the Zanja Madre stood in the middle of the plaza, which was then still a rectangle probably 200 feet by 300 feet.

An adobe structure stood on a hill behind the La Fayette Hotel and restaurant, built between 1850 and 1856. That adobe was at first used as a jail and later turned into a residence. Prudent Beaudry later leveled that hill.

The La Fayette Hotel was located next to an open space of dirt, behind which ran was called “Nigger Alley” by the Americans, “Calle de los Negros” by the Spanish-speaking people – today Los Angeles and Arcadia Street behind the Chinese American Museum near the 101.

In the 1850s, this 500 square foot place was lined with – according to a letter written on June 29, 1882 by Horace Bell with “saloons, gambling hells, and disreputable dives. It was a cosmopolitan street. Representatives of different races and many nations frequented it. Here the ignoble red man, crazed with aguardiente, fought his battles, the swarthy Sonorian plied his stealthy dagger, and the click of the revolver mingled with the clink of gold at the gambling table when some chivalric American felt that his word of ‘honah’ had been impugned.” https://ladailymirror.com/2011/10/13/calle-de-los-negros-a-vanished-landmark/. (Retrieved 6/6/16).

In 1861, the City and the County built the “Clock Tower Courthouse” across the street from Temple city hall/market house. Jail Street became Court Street, which went up to the then undeveloped hill on which Beaudry was to develop Bunker Hill. There is no longer a Court Street downtown, but there is West Court Street, which snakes from the eastern edge of the Vista Hermosa Park, continues below Temple and below Echo Park Lake and ends near Alvarado.

In 1928, the city straightened the triangle of land crossed by Main, Spring, Market, Court and Franklin Streets and built today’s City Hall on it, now bounded by Main, Temple, First and Spring Streets.

The answer to the question of where did Los Angeles start is impossible to answer for now. Some day, archeological findings in a parking lot excavation or under a sewer pipe may give information about when Yang-Na began. A short answer is that in 1769, the huts and central space of Yang-Na were between City Hall and the Triforium.

Yang-Na’s was larger than the village hut area – so although it is not true that the Olvera Street area near the plaza downtown was the “birthplace of Los Angeles” in 1781 — it might well have been its birthplace thousands of years ago.

The pueblo rebuilt, in 1818, in about the area native people chose as the best location for their primary village.

Selected other sources:

Translators and those trained in Colonial Spanish calligraphy and history compiled original writings from the time just before and after the founding of the pueblo of Nuestra Senora de los Angeles in 1781. These are contained in The Founding Documents of Los Angeles: A Bilingual Edition, edited with an Introduction by Doyce B. Nunis, Jr. (Historical Society of Southern California and the Zamarano Club of Los Angeles 2004). This is a second revised edition. The first revised edition was published in 1931, printed in the Annual Publications of the Historical Society of Southern California, Volume XV, Part I. This collection includes Charles Lummis’s translation of Neve’s Reglamento.

John Bankston, Fray Juan Crespi (Mitchell Lane Publishers 2004). This is a book from ages of about 8-12.

J. M. Guinn, “From Pueblo To Ciudad: The Municipal and Territorial Expansion of Los Angeles,” Southern California Quarterly (Los Angeles County Pioneers of Southern California, Historical Society of Southern California 1907), Volume VII, page 216, et seq.

Steven W. Hackel, Junipero Serra: California’s Founding Father (Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Strauss and Giroux 2013). See also, https://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/history-of-san-gabriel-arcangel-mission.htm.

Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering, “Four Leagues Square.” http://eng.lacity.org/aboutus/4leagues/4leagues.pdf, In 1850, the California legislature decided “4 leagues square” actually meant “four square miles,” but the City brought its claim of ownership to the Land Act Commission and won back its “4 leagues square.”

Los Angeles County document about County Supervisor Antonio Coronel. http://file.lacounty.gov/lac/acoronel.pdf. (Retrieved 6/28/16)

W. W. Robinson, Los Angeles from the Days of the Pueblo (California Historical Society (1959)

Starr, Kevin, Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era (Oxford University Press 1986)

D. J. Waldie, Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir (St. Martin’s Press 1997)

https://archive.org/stream/reminiscencesofr00bellrich/reminiscencesofr00bellrich_djvu.txt. (Retrieved 6/11/2016)

https://archive.org/details/sixtyyearsinsout00newmrich. (Retrieved 6/11/16)

Visit:

Angel’s Walk: http://www.angelswalkla.org/pdfs/AWLA_UNIONSTATION_GUIDEBOOK.pdf.

City Hall

The Sepulveda House

The Triforium

The Ranger Station in Griffith Park, once the Feliz adobe

Lightfoot and Parrish recommend the Malki Museum (www.malki.museum.org), the oldest all Indian museum in Southern California, located on the Morongo Indian Reservation. “The annual Malki Fiesta attracts large crowds of both Indians and non-Indians to the reservation, who sample local Native foods, view and buy Indian crafts, and enjoy Indian dances.” The authors also recommend the Satwiwa Native American Indian Culture Center (www.satwiwa.org), a partnership between Chumash and Tongva people and the National Park Service.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.