Mary Reinholz Writes About Harlan Ellison

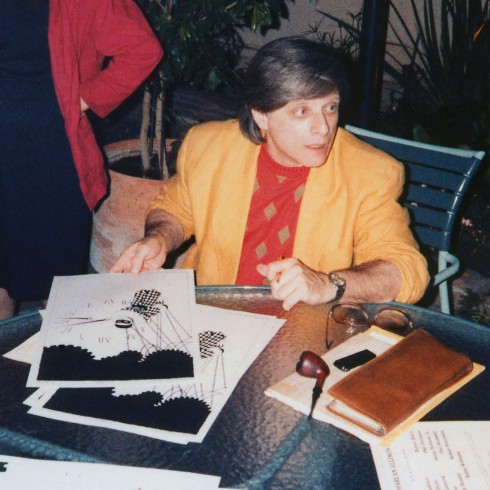

All photos are by Jill Bauman. This is Ellison at the L.A. Press Club.

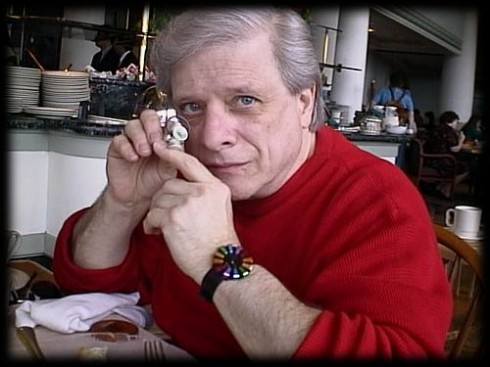

Ellison with the green lantern ring

Ellison with wife Susan

MARY REINHOLZ

Way back in 1965, not long after Harlan Ellison had completed a screenplay called “The Oscar,” he was confronted by Frank Sinatra in a pool room at the Daisy, a private Beverly Hills club on Rodeo Drive.

The crooner, formally attired and holding a drink, took exception to Ellison’s game warden boots, according to New Journalist Gay Talese, who wrote a celebrated article for Esquire, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” that cites a clash between the two men.

Sinatra, close to 50 at the time and accompanied by four friends, asked the jockey-sized Ellison three times if he knew what the make of his boots was. Three times Ellison replied in the negative, finally telling Sinatra, “Look, I dunno, man.”

Talese recounted how the poolroom fell silent. Sinatra sauntered over to the much younger man, someone he didn’t know. “You expecting a storm?”

Ellison snapped back. “Is there any reason why you’re talking to me?”

“I don’t like the way you’re dressed,” Sinatra said.

“Hate to shake you up, but I dress to suit myself,” Ellison said.

The exchange, wrote Talese, lasted three minutes even after Sinatra told Ellison that his screenplay “was a piece of crap.” Twice.

All that went down more than 50 years ago. Ol’ Blue Eyes, who could have ruined more than a writer’s career, is long gone and Ellison, 81, a combative (some say crazy) little guy with big cajones, now has enough literary accolades to fill a panel truck with suitably dark windows. He’s still writing in his fashion despite a debilitating stroke in 2014.

“Since the stroke, my right side is still paralyzed, but I can still type with two fingers,” he says during a recent call to his hillside home off Mulholland Drive. “I still get around. I get up and get into the wheelchair. I went to a [science fiction] convention in St. Louis and they all seemed to take it well. No one stoned me, even though I have this reputation of being a tough old bagel that’s hard to chew. A couple of times, I’ve done (spoken word) recordings. But mostly I lie in bed and watch the ceiling.”

It’s hard to imagine Ellison, a longtime friend of this writer, just watching the ceiling. Over the decades, he has stood up to studio heads, sued film and TV producers, punched a critic in public, gone through four divorces, battled depression and kept on writing. He says he has always had his own voice and never imitated anyone — apparently not even when he was using a pseudonym, Cordwainer Bird, to signal readers that his work had been mangled by varied powers that be.

In more recent years, he had this to say to more than 240 people who had distributed his writings on the Web without his permission: “If you put your hand into my pocket, you’ll drag back six inches of bloody stump.”

Yes, the legendary Los Angeles author can make Tony Soprano’s boys sound like pussycats.

That’s not surprising since Ellison, best known for his New Wave science fiction (a label that he loathes), has also written hardboiled crime stories and crossed over into many other genres during a career spanning six decades.

“I think he’s an original,” says David Ulin, the Los Angeles Times’ former book critic and a lecturer at USC’s Master of Professional Writing program. “I read him as a little kid and love his work. He’s versatile and uncategorizable. He works across the media with graphic novels, comic books, everything. I think there’s a really interesting sensibility at the heart of his writing: curiosity and righteous indignation. There’s a deep emotional chord.”

Back in the Day

At intervals during our conversations, Ellison shouts out questions to Sharon Buck, his longtime assistant, who is in another room, and to his fifth wife, Susan Toth, a petite woman from the British Midlands. They met in England and have been married 30 years.

Ellison also remains deeply wedded to his work. December saw the hardcover publication of “Can & Can’tankerous,” which includes previously uncollected short stories and a tribute to Ray Bradbury, and in September the ninth edition of “Ellison Wonderland” was released; the collection was first published 52 years ago.

A third Ellison biography is expected to be published next year. It’s an authorized one written by Nat Segaloff, who has penned several books about Hollywood royalty, the latest on director John Huston. In “Dreams with Sharp Teeth,” a 2008 documentary directed by Erik Nelson, there are interviews with Ellison who admits he once sent a dead gopher to a publisher in the mail and others with his deceased crony Robin Williams, who committed suicide in 2014.

One of Ellison’s more notorious friends is the long dead L. Ron Hubbard, founder of the controversial Church of Scientology, which has a branch in Old Pasadena at 35 S. Raymond Ave. He met him early in his career, when they were both writing pulp fiction in New York.

“Oh God, Ron and I were friends. I knew Ron very well,” Ellison says. “Back in the 1940s, he was a pulp writer and he would write on a big roll of butcher’s paper, and he’d rip off the pages. When he was done, he would take them to John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding Science magazine. I met Ron in Brooklyn. He was complaining about working too hard and wanting more money. Lester del Rey (a well-known science fiction writer) said he should write articles. He came out with (theories) of Dianetics and John went for it. We were all laughing. Everybody knew it was bullshit. But it seemed like a good idea.”

Elllison said Hubbard used to give him advice because “I was a dangerous little guy in those days.”

He joined a street gang in Brooklyn’s Red Hook district to write his first novel, “Web in the City,” and soon after was drafted into the Army in 1957, serving two years. He came to Los Angeles in 1962. Ellison’s work habits show a kind of military discipline. In the aftermath of his stroke, he pecks out words on a portable typewriter, usually an Olympia, which he keeps at his house in Sherman Oaks. Crammed with pop culture artifacts and books, it’s nicknamed the Lost Aztec Temple of Mars.

Wildly Prolific

The second child of a dentist who did time for transporting bootleg liquor, Ellison was born in Cleveland, Ohio and grew up in Painesville, the only Jewish kid in his elementary school. He says he always wanted to be a writer and has been using typewriters since age 14. He tried working with laptops, but says they make mistakes. That would be unacceptable for a man who has produced perfectly spelled and double-spaced scripts while sitting in book store windows, pounding away on the keys at 120 words per minute in part to promote his view that writing is a craft and “not magic,” according to Segaloff.

Paul Krassner, a founder of the Yippies and former editor of The Realist, his satirical magazine that ceased publication in 2001, recalls a crowd gathering to watch Ellison typing up a storm in a department store window and wondering why a writer about the future would work with a relic of the past.

Krassner calls Ellison “very opinionated, but fearless of a negative response. For example, he wrote an anti-marijuana introduction to my anthology, ‘Pot Stories for the Soul: An Updated Edition for a Stoned America.’” Krassner sent Ellison $100 for his contribution to “Pot Stories,” but says he would only accept $10.

It should be said here that Ellison doesn’t smoke anything. He gave up smoking a pipe after suffering a heart attack in 1994, and has undergone quadruple coronary artery surgery. He also doesn’t drink.

What moral compass guides this gifted but stormy scribe?

“Harlan is a situational ethicist,” says Segaloff. “Like those of us who were raised without constraints, we impose our own, more severe morality upon others. Harlan believes that a person who wrongs him (or others) and, worse, does not take responsibility for his actions, deserves what he gets.”

Indeed, Ellison has gone to great lengths to see that people who caused him grief get theirs, something evident during his college days. He jokes about receiving a degree in the “pharmacology of horse manure,” but acknowledges he was thrown out of Ohio State University, reportedly for hitting a professor who had disparaged his writing.

For some 20 years after that incident, Ellison sent the professor copies of every piece of writing he published and every award he received. For starters, that would include multiple Hugos, Nebulas, Edgars and PEN’s Silver Pen Award for his columns in LA Weekly defending the First Amendment.

He’s touted as wildly prolific, but reports of Ellison’s exact output vary. He appears to have written at least 75 books and published more than 1,700 short stories, dozens of teleplays and screenplays, plus comic books, audio books, and arts criticism — the latter including two collections of his television columns, “The Glass Teat,” for the Los Angeles Free Press. He’s also edited two respected short story anthologies: 1967’s “Dangerous Visions” and 1972’s “Again Dangerous Visions.”

His older short stories are classics in speculative fiction, the term he prefers to use to describe his writing. “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream,” a post-apocalyptic fantasy about the last five people on Earth being tortured to death by a computer, was included in “The Top of the Volcano,” a 2014 collection of 23 of Ellison’s award-winning stories. Here are some opening lines:

“Limp, the body of Gorrister hung from the pink palette; unsupported — hanging high above us in the computer chamber, and it did not shiver in the chill, oily breeze that blew eternally through the main cavern. The body hung head down attached to the underside of the palette by the sole of its right foot.”

From the same collection, Ellison’s “A Boy and His Dog,” set in a Southwestern American wasteland after a nuclear war, garnered a 1970 Nebula award for best novella. Don Johnson starred in the 1975 film — which the late radical feminist writer Joanna Russ, a friend of Ellison, denounced as outrageously sexist. Even Ellison protested the “chauvinistic” sentences in the movie’s ending. In the following passage from the printed version of “A Boy,” his tough guy narrator muses about the doomed “chick” he’s about to rape:

“She was brushing out her hair. It hung way down the back. The flashlight didn’t make it clear enough to tell if she had red hair or chestnut, but it wasn’t blonde, which was good, and that was because I dug redheads. She had nice tits, though. I couldn’t see her face, the hair was hanging down all smooth and wavy and cut off her profile.”

Knight magazine, a now defunct West Hollywood publication modeled after Playboy, published “A Boy and his Dog” as a cover story in the late 1960s with an illustration by Ellison’s artist friends Leo and Dianne Dillon, according to Beverly Hills writer Jared Rutter, a former editor at Knight.

Rutter has warm memories of working with Ellison. “He was such a fire-bringer. His energy was almost demonic,” he recalls. “For two or three years he wrote many stories for Knight and Adam (a brother publication). He also brought in as contributors many of his colleagues, like Norman Spinrad and Theodore Sturgeon. He always seemed to me very generous.” Rutter adds, “But you wouldn’t want to mess with him.”

‘That’s how I do it’

Ellison, famously litigious, wrested a settlement in 2009 from CBS Paramount Television for failure to pay him royalties from licensing deals earned by the mega-corporation from his popular 1967 “Star Trek” episode “The City on the Edge of Forever.” And that’s for starters. Ellison claims to have won all of his lawsuits, including one against AOL.

Along the way, he successfully defended himself against a 1979 libel suit brought by Michael Fleisher, author of DC Comics’ violent “Spectre” series. Ellison had dubbed both Fleisher and the series variously as “insane,” “bug fuck” and “derange-o” in an industry magazine interview. Los Angeles lawyer, Henry Holmes Jr., was not available for comment.

Science fiction author Ben Bova, a six-time Hugo Award winner, reportedly joined Ellison in a lawsuit against Paramount and ABC for plagiarizing portions of their short story “Brillo” for the short-lived 1976-77 television series “Future Cop.” They won a judgment for $337,000.

Bova believes the media has turned Ellison into an enfant terrible. “His reputation has been created largely by people who don’t know him. Harlan has always struck me as like a Jewish rabbi who is horrified by the way the world runs and he wants to make it right. He has justifiable anger. Above all else, he’s one of hell of a writer.”

Notes Bova: “Harlan is a good friend and a much better person than people realize.”

Ellison, whom the Washington Post has called “one of America’s greatest living short story writers,” joined the bloody 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He was a friend and mentor of the late African-American novelist Octavia E. Butler, the first black woman to achieve international prominence within the largely white male bastion of science fiction writing. She grew up in a racially mixed neighborhood of Pasadena. Ellison was one of three people to whom Butler dedicated her 1994 book “Mind of My Mind.”

Butler, who died in 2006 at 58, was an unknown young writer when she first met Ellison at a workshop. “She was one of my students and came to me as part of a (program) the Writers Guild had decided to put together to bring in Latino and black female outsiders,” he recalls. “She came to me with a story. I took a look at it and knew how good it was. We talked about it and workshopped it and it went on from there. I was just one step on her way up. She did it all herself. She was a stalwart woman.”

Ellison claims he has no idea where his creativity comes from, but notes that he has written for the markets from the get-go.

“I take my place at the table and ask myself, ‘What will I do today?’ That’s how I do it,” he says. “I think you’re at the cutting edge when you stay close to the heart and draw a little blood.”

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.