Honey And Lands Of The Sun

By Honey van Blossom

(Honey is a Belgian Marxist former strip-tease artiste)

Honey and Lands of the Sun

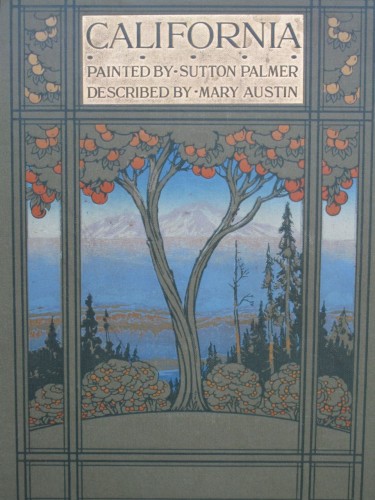

In 1913, Mary Austin lived for a time in London. According to Lawrence Powell, in California Classics: The Creative Literature of the Golden State (First published in 1971), Mary Austin was asked to write a series of essays to accompany British painter Sutton Palmer’s watercolors of California. Adam and Charles Black published California, Land of the Sun in 1915. The book did not appear in the United States until 1927, published without the paintings as the Lands of the Sun.

Powell wrote:

“It is a lyrical hymn to California, its contours and configurations of seacoast, valleys and mountains. This book holds a special place in my remembered reading because of the circumstances in which I discovered it. The place was Paris on a rainy afternoon in May, mild and yet too wet for walking. I sheltered under the umbrella of a bookstall on the…Quay of the Goldsmiths – and there I chanced upon a worn copy of The Lands of the Sun”

I was more fortunate than Lawrence Powell. On a summer day in 1985, I walked into the Santa Cruz Public Library in downtown Santa Cruz, An oil painting of Josephine McCracken in old age hung on the wall. McCracken had not only been a prolific writer and Ina Coolbrith’s close friend, she had helped save the last of the Old Growth redwoods growing in the Santa Cruz Mountains. From a page on the library’s website I retrieved thirty years later:

“In an article published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel on March 7, 1900, she wrote of the plight of the giants that were destroyed, not only by fire but by axe. Her message was quickly taken up by nature lovers throughout the world. Through the efforts of these concerned people the Sempervirens Club of California was founded and in March, 1901, the first California Redwood Park was founded at Big Basin, near Boulder Creek, in the northern Santa Cruz Mountains.”

I went to the shelves. At some point in the library’s history, a librarian had ordered a copy of the original 1915 edition with the charming color plates. It wasn’t kept in a vault. I checked it out.

For the first and only time in my life, I thought of stealing a book. I claimed I lost it. The first librarian, the one who ordered the book, was probably long dead. One of her successors said I would have to pay $50 in fines and penalties.

I came to my senses. Some day, some one else – a teacher, a librarian, an historian, an environmentalist, someone – would find that book if I returned it to the library. As it turned out, an El Nino would destroy almost all of the books and photographs I had collected about California literature, which I kept then in my younger daughter’s dilapidated Berkeley garage.

I returned the book. At the end of this conclusion is a link to a digitized reprint of the first book with the paintings still clear. Later editions contain blurred copies of the paintings.

Sutton Palmer lived between 1854 and 1933. He showed paintings in New York in 1880, so the paintings may have been created as long as thirty years before Mary Austin wrote her essays about them and so may show an earlier California. My assumption is supported by Austin’s passage:

“Too much of what I describe has utterly vanished, too much more has utterly changed, so blatant and bristling with triumphs over the unresisting beauty of the wild, that it would be difficult indeed for one to lose himself in that delighted sense of the whole that was the special privilege of those who came to California in the last quarter of the century and before it.”

Austin began with California Native American stories. Those stories may not be accurate. She didn’t translate original oral literature but re-wrote them as what she called “Re-expressions.” Years later, Theodora Kroeber would “re-express” California native myths, and Theodora’s daughter Ursula Le Guinn would imagine a future indigenous world in the Bay Area in her utopian Always Coming Home (1986).

In 1923, — unmentioned in Powell’s California Classics essay — Austin published The American Rhythm, which compared modern (1920s) poetry with American-Indian songs and chants from the entire continent. Austin’s writing after her first young book – Land of Little Rain – comes across as stilted, as pretentious and as humorless as she personally came across to people, but her insights were remarkable. Austin included in The American Rhythm the deep and unusual perception that traditional Indian dancing was also a form of oral literature.

California’s first people had no boundary between their art forms in the abstract designs woven into baskets, dance, petroglyphs, myths and songs. Stepping back and looking at the integration of the first people with their natural environment, it is impossible for me to distinguish any yet known aspect of their lives that was not art and that was not spiritual.

Austin concluded Lands of the Sun with a premonition of a time when a writer of the future will create a work that integrates the stories of all of the state’s people and create a new vision that encompasses its wildness.

Austin was, it seems, aware that she was not that writer. That was not like her. She told Gertrude Atherton, “You know, I am the best woman writer in the world.” Gertrude said, “Mary, that isn’t true.” Austin, having no sense of humor in what Gertrude thought of nonetheless as Austin’s “prodigious” brain, did not laugh.

The text of the two versions may differ; that is, I don’t recall this passage that Lawrence Powell cited:

“’In two or three generations, when towns have taken on the tone of time, and the courageous wild has re-established itself in by-lanes and corners, a writer may be born, one instinctively at one with his natural environment, and so be able to give satisfying expression to that wholeness. In the meantime let this book stand as a marker, if for no more than the sketched pattern of a suggested recovery.’”

The convention today is to say that “a generation” is either twenty or twenty-five years.

I don’t know what Austin meant when she wrote in 1915, but we have not yet had the time when the courageous wild has re-established itself, and I do not think the cities have taken on the tone of time, and so far it seems to me that no one writer could ever give a satisfactory expression of this island on the land.

Suggested reading:

Lawrence Powell, California Classics (Capra Press 1971)

http://scplweb.santacruzpl.org/history/people/josmc.shtml. (Retrieved August 21, 2015) Notice the photograph of Josephine MacCracken as an old woman standing next to the young actor Zasu Pitts, who performed in the Von Stronheim film Greed, an adaption of Frank Norris’s novel MacTeague. Zasu Pitts grew up in Santa Cruz.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/api/volumes/oclc/2487449.html. University of California digital copy of California, Land of the Sun. Go to “Full Copy.” (Retrieved August 21, 2015) The paintings unfortunately are blurred.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.