Two Hills in Concord

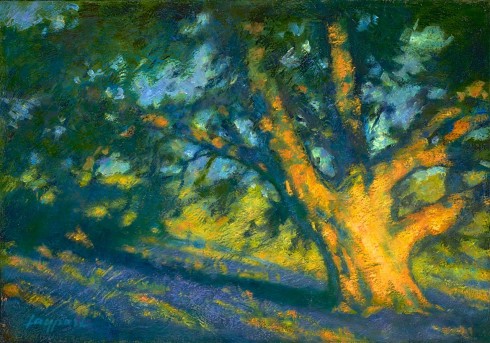

TWO PAINTINGS BY BOB LAYPORT: THE HILL AND THE OAK

BOTH PAINTINGS; Copyright 2015 Bob Layport

BY PHYL VAN AMMERS

OUR SPECIAL NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CORRESPONDENT

A multi-use trail that runs behind schools, houses and shopping malls from a road near the Delta at Bay Point down to Walnut Creek is a lesson in history. That history is camouflaged by the transformation of the East Bay by freeways, water and sewage systems, and intense real estate development.

To many Californians, the geography of that area is unknown. I have to start off with, “Go east from Oakland.” Most people know where Oakland is. Even those who know where Oakland is don’t know anything about the California Delta.

The Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, or California Delta, is an expansive inland river delta and estuary in Northern California in the United States. The Delta is formed at the western edge of the Central Valley by the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and lies just east of where the rivers enter Suisun Bay.

Since the mid-19th century, most of the region has been gradually claimed for agriculture. Wind erosion and oxidation have led to widespread subsidence on the Central Delta islands; much of the Delta region today sits below sea level, behind levees earning it the nickname “California’s Holland.” Much of the water supply for central and southern California is also derived from here via pumps located at the southern end of the Delta, which deliver water for irrigation in the San Joaquin Valley and municipal water supply for southern California.

I spent my first year here lost. I don’t have GPS. If I had it, I’d turn it off because the GPS voice is inhumanly patient and insistent. My daughter has lived in this area since 2001. Without GPS, she’d to this day be lost.

The first episode of the American occupation in Concord and Walnut Creek was agricultural, starting with small orchards and dairy farms and wheat fields, and then comprised mostly of orchards with dirt roads separating the towns. There are still orchards, horse ranches and farms in the countryside located on back routes punctuated by those giant houses with no yards and shopping malls.

These newer developments look like towns designed by aliens from outer space might look like if the aliens had no concept of joy or beauty.

The Contra Costa Canal Trail is an asphalted route for bicyclists and walkers and runners. The trail runs from Willow Pass Road in Concord — interrupted by Treat Boulevard and by smaller street crossings with signals — to the city of Walnut Creek. The City of Concord barricaded the center divider on Treat as if that would stop bicyclists from crossing the busy thoroughfare. A sign directs walkers and bicyclists uphill to a crossing signal. Most people ride downhill instead and lift their bicycles over the center divider where there is no barricade.

Willow Pass Road continues from that end of the trail up to and then under the California Delta Highway (Highway 4), where it becomes Bailey Road to the Port Chicago Highway.

On July 17, 1944, at the Port Chicago Naval magazine, 320 sailors and civilians died and 390 were wounded when munitions detonated. The casualties were mostly enlisted African-American sailors, who had received no training in loading munitions. The blast destroyed houses and stores for miles around. The unsafe conditions continued. A month later, fifty sailors refused to work under those conditions. They were court-martialed and convicted of mutiny. That protest – and other protests against race-biased working conditions in the Navy during 1944 and 1945 — led to the desegregation of Navy forces.

At the end of the Contra Costa Trail, the bicyclists can go into the City of Walnut Creek, now an upscale city with high-end stores and pricey homes. Or they can head towards Pleasant Hill, or continue to Pleasanton. The entire route is also called the Iron Horse Regional Trail. Between the cities of Concord and Pleasanton the route follows the Southern Pacific Railroad right-of-way established in 1891 and abandoned in 1977.

A portion of the Iron Horse Regional Trail – that part between the top of Willow Pass Road near the Delta, not far from Port Chicago to Walnut Creek – traverses this almost incomprehensible suburban geography along the routes taken by the first non-Indian people. They saw a much different landscape: an arroyo, two hills, marshes, animals, oaks, and an Indian village. This was the primordial East Bay, the land as it was for ten millenniums.

In 1772, Spanish explorers led by Captain Pedro Fages and Father Juan Crespi became the first non-Indians to cross that area. In 1776 Juan Bautista de Anza expedition followed the trail, beginning in Hermosillo in Sonora with recruited settlers and animals, stopping at the Mission San Gabriel, continuing up the coast to San Jose, and then looping around through what would one day be Concord to found the mission at Yerba Buena. The Delta de Anza Regional Trail follows the de Anza expedition’s route. The expedition included Juan Salvio Pacheco. His grandson Salvio Pacheco founded what he called “Todos Los Santos,” which the Americans called “Concord.” All that is left of Todos Los Santos is the plaza in downtown Concord, Salvio Pachecho’s adobe transformed into a business complex on Arroyo Street, and Fernando Pachecho’s adobe built in 1846, now used as an office.

On April 2, 1776, the expedition camped at an arroyo with wholesome water they named the Arroyo of Santa Angela de Fulgino, now the arroyo into Walnut Creek.

The next morning they set off in a North-Westerly direction to what was later called Willow Pass and reached a hill, following the Crespi description of the area. From the top of the hill, they saw the river divided into three branches. They saw they could not get through the marshes.

De Anza’s diarist Pedro Font wrote on April 3, the day after the expedition camped at Walnut Creek that they came across a large herd of deer about “7 spans” high, with antlers two yards across. http://www.anzahistorictrail.org/visit/explorer

They continued to the East-Northeast for two and a half leagues (A “league” was about 2.6 miles.), until they found a Rancheria of about 400 Indians, who greeted them peacefully and “even with trepidation” and gave them gifts of salmon, and the Spanish reciprocated with “the usual presents.”

The expedition continued for another league to another hill, and there Anza saw a confusion of water, tule beds, forest and a vast plain (the Central Valley). To the east of the plain rose the Sierra Nevada, white from the summit down. He saw then that the river he had named Rio de San Francisco was not a river (It was the Delta.) He descended the hill and they camped for the night at an abandoned Rancheria in a grove of oaks at the location of what is now Antioch, and they gave up trying to reach Point Reyes and returned to Monterey.

The first hill de Anza climbed had to be what is today called Lime Ridge, a dedicated open space. Six and a half miles in a North-Northeasterly direction is the top of Willow Pass Road, where it descends to Bay Point. Because the bicycle path stops at Willow Pass Road, a bicyclist has to go along the gravel and weed road shoulder up to what is called the De Anza Trail. The bicycle trail I take, therefore, approximates the route that the De Anza expedition took 230 years ago.

The trail today, starting at Walnut Creek, passes over what was once a river – probably the “arroyo.” (An arroyo is a watercourse in an arid region.) Oaks and California walnuts shade that part of the route. It crosses Bancroft – where historian H. H. Bancroft had his rural home and raised fruit trees around the turn of the twentieth century. The corner of Bancroft and Treat is a shopping mall, and the trail goes behind it and behind the fenced backyards of suburban houses.

In summer at dusk I take the short cut over a little bridge and up a dirt road through part of the Lime Ridge Open Space.

The ridge is above the sound of automobile traffic. All I hear at this place is wind and an owl. Two people walk slowly past me followed by Rin Tin Tin dogs wearing bells on their collars. I hear the bells. The tinkling bells grow distant. The people are gone. The sky deepens.

I am alone with the swoop of hill going upwards. Dry grass grows on the hill, and grass rustles. The brush on the hill moves in the wind.

At the summit of the ridge, another path winds up a neighbor hill to my left. To my right, are other hills and at the end of them Mt. Diablo rises. There are no houses visible, and no telephone and electrical wires can be seen. Coyotes and rattlesnakes and burrowing animals live on the ridge but I haven’t seen them.

This meditative place is what California was like in its dry seasons since the last Ice Age except then there were tremendous herds of elk, deer and antelope and the grizzly bears. Salmon swam in the streams, The Bay Miwok, a shamanistic people settled here about 10,000 years ago, but earlier migrations had walked from the north and passed through it. Metal clanged for the first time in 1772. Horses neighed for the first time in that part of California. The Fages explorers and the de Anza expedition left nothing behind but grass bent under boots and hooves.

For about 10,000 dry seasons, all people saw on this ridge was what I see when I take the short cut. Ten thousand years ago, an early Anatolian people developed agriculture for the first time near the Tigres and Euphrates Rivers. They built the first temple at Gobekli Tepe near modern Urfa, and then the first agricultural city. That’s how long ago ten thousand years is. It was the time re-told in the Bible’s Book of Genesis.

California’s first people heard the inhalation of breath, and then the wind and the doves. Their shamans translated for them nature’s spirits: the spirit I see moving in the long grass and imagine in the bending branches. They heard the wind and the ancestors of the owl I hear. Their minds were quieter than ours.

I bought two oil paintings from Bob Layport. He is an artist who lives in Glendale. The street to his house goes towards the giant San Gabriel Mountains. One of the two paintings is of brush, grass and shadows. A print of this painting accompanies this essay. The print does not show up as well as the original painting, which conveys quiet and profound mystery. Words get in the way, words like “capture” and “conveys.” As soon as I use words, mystery dissipates.

In another direction, I walk in the morning through this suburban neighborhood to Newhall Park, once called Turtle Creek, and there is a creek at the top, and a real estate development on one side of it called Turtle Creek. I cross Treat Boulevard and walk up another incline and I am then on another ridge. Majestic oaks grow on this ridge. This ridge is also high, and from its highest point – a memorial to men and women killed in two of our wars – I can see vast distances as well as I can from Lime Ridge.

Most California Indians developed the acorn culture sometime after the disappearance of the mega fauna. The native people wove large baskets to contain the acorns, and these baskets hung from the powerful arms of the oak trees. All trees have had symbolic meaning since very ancient times. The Norse people came from Central Asia and brought the idea that the mistletoe that hangs in oaks was the secret life of the oak. The oak is the golden bough. In some versions of the Greek myth about Jason, his golden fleece is hung from an oak. Jesus’s cross was made of wood but no one agrees on the tree it was made from.

Sir James George Frazer (1854-1941) published his twelve- volume The Golden Bough in 1922. Frazer wrote, “The worship of the oak tree or of the oak god appears to have been shared by all the branches of the Aryan stock in Europe. Both Greeks and Italians associated the tree with their highest god, Zeus or Jupiter, the divinity of the sky, the rain, and the thunder. Perhaps the oldest and certainly one of the most famous sanctuaries in Greece was that of Dodona, where Zeus was revered in the oracular oak. The thunderstorms which are said to rage at Dodona more frequently than anywhere else in Europe, would render the spot a fitting home for the god whose voice was heard alike in the rustling of the oak leaves and in the crash of thunder.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) wrote a poem that school children used to memorize. My stepfather – who would be 100 years old if he were alive now – recited the poem about once a month. By the time I was in school, we did not memorize any poetry.

This is Longfellow’s poem:

“Eliot’s Oak”

“Thou ancient oak! whose myriad leaves are loud with sounds of unintelligible speech. “Sounds as of surges on a shingly beach,

Or multitudinous murmurs of a crowd;

With some mysterious gift of tongues

endowed,

Thou speakest a different dialect to each;

To me a

language that no man can teach,

Of a lost race, long vanished like a cloud underneath thy shade, in days remote,

Seated like

Abraham at eventide

Beneath the oaks of Mamre, the unknown

Apostle of the Indians, Eliot, wrote

his Bible in a language that

hath died

And is forgotten, save by thee alone.”

“Mamre” may be a reference to a Canaanite cultic shrine dedicated to the supreme, sky god of the Cananite pantheon. From pottery shards found in Palestine, the shrine was in use from 2600 to 2000 BCE. In the biblical account, Mamre was the site where Abraham set up his tents to camp, built an altar, and heard divine tidings from three angels.

Sacvan Bercovitch, in The Cambridge History of American Literature: Volume 4, explained that John Eliot’s Indian Bible, printed in 1663, was the first Bible printed in America. In Longfellow’s sonnet, Eliot’s Bible is a figure for the defeat of translation. Every line in the sonnet is devoted to linguistic imagery; but every line marks linguistic default. The leaves, though ‘loud with sounds,’ amount only to ‘unintelligible speech.’ The oak has a ‘mysterious gift of tongues,’ speaking in myriad dialects, but as a language that ‘no man can teach.’ As for Eliot’s translation, for all of the devotion of its task, in the end it too is unintelligible, the emblem of a ‘lost race,’ monument to a ‘language that hat died and is forgotten.’ ….

I read this sonnet a little differently. Eliot referenced the antiquity of the oak symbol in the Bible. Abraham and his people were unable to interpret the oak’s meaning but Mamre – the site of oak worship – was the “apostle of the Indians,” meaning that the Indians for whom the Bible was translated understood the language “that no man can teach.” That is, the language of nature: the oak’s secret that penetrates the heart of the supreme being, the god that lives in the sky, cannot be understood through words. It is Longfellow, I believe, who has lost the language of nature and who yearns for what he is blind to.

The oaks that grow in Newhall Park are powerful architecture that rise from the earth, draw growth from the earth, and create food and shadow. The sky seen through the dark leaves is more intensely blue.

Layport created a series of oak paintings. A print of the one I bought accompanies this writing. This print also is too flat to show what the original shows.

The oak in Layport’s painting shows a squatter oak than those giants that grow in Newhall Park. In the painting, the oak rises like a man’s muscled hand – a hand with golden skin — and the tree lightly casts its dark green leaves, fishing in the sky for the sun.

All of the oaks I’ve seen do not have that golden skin. That color in the painting is more like the color of eucalyptus when its outer bark peels back. The oaks I’ve seen have something more like alligator bark, rather dark, not brown but containing duller grays, browns, and if you look hard, blue. But the painting is of early morning, so it may be that Layport painted morning light transfiguring the bark to a golden color.

Layport’s oak is not a real tree, exactly copied from nature.

His tree is Longfellow’s oak: the spirit tree, god, and also it is the hand of a man reaching and creating. Sometimes, as the light in my house changes, I see the tree differently – as the spirit of humanity, the humanity I prefer to believe co-exists still with its evil side.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.