Mary Reinholz’s “Exit From Eden” Continues

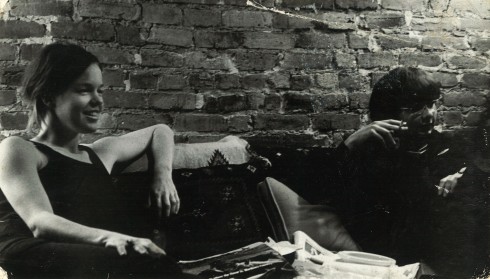

This is Mary (left) with a dark haired yippie friend in East Village, 1970, shortly after returning from a Black Panther convention in D.C.

Chapter 11

“You won the derby,” Jason Slade said in an early morning telephone call to my room at the Chelsea Hotel. His tone was breezy as he explained that I had been picked out of a field of 10 competitors to write a column on women’s liberation for the Daily Bugle’s Sunday magazine. “We like your style,” he added magnanimously, invoking the royal “we“ as if more than one guy in a corporate cubicle had read my writing samples. “Now the fun begins.”

I mumbled something inane. Other writers might have babbled joyously on learning from a top editor that they had been given a forum at a daily newspaper whose Sunday circulation was the largest in the U.S. But unbeknownst to Slade, I was also a fugitive, mainly worried about staying out of jail for offing a man in Arkansas. This column was a feather in the cap of a career girl, but it could bring me into fierce contact with the law. I felt tension gathering, like a metal band clamped around my forehead.

Just the other day, I had heard the crackle of a police radio outside my door. At first I expected the worst: NYPD boys in blue sent by the Feds to arrest a killer girl hiding in a world famous Bohemian haunt. Then I heard a woman sobbing, “It’s my fault,” and a man trying to comfort her.

Curiosity overcame my fear and I walked barefoot into the dimly lit hall, spotting

a beefy patrolman talking to the two people, his back turned to me. A door to a suite was open and I inched towards it. Inside, on a king sized bed, lay the body of a handsome black male about 30 years old, wearing only red shorts, his eyes open in a blank death stare. A hypodermic needle was stuck in his right forearm. The color TV he faced was still playing.

The cop whirled around. “What choolooking at?” he shouted. “Lady, get outta here!”

“I’m a reporter, officer,” I found myself saying. “What happened here?”

“You’re nobody here,” the cop barked. “Get back to your room!”

Now Slade’s voice broke through my reverie of yesterday’s grief and chaos, reminding me of my elevation from nothingness to a prestigious slot in the tabloid press.

“We’re also going to publish your sample column on those death threats against Harvey Jewell as a hard news story in the daily tomorrow, “ he said cheerily. “Nice job, Ryder. A porn king targeted by firebrand feminists. It’ll be on page 3, one of the first things straphangers will read on the subway heading to work.”

His enthusiasm was soothing but the tension remained. I winced when Slade said the pay for my weekly column would be $100 a pop once it started two weeks from next Sunday, but said nothing.

“I’m thinking of calling the column ‘She,’ Slade mused. “My wife suggested, ‘Venus Rising’ but that’s too boho, too artsy—not the Bugle’s style.”

“How about ‘The Feverish Feminist’?’’ I suggested, suddenly getting a case of the giggles as Slade attempted to boil down a mass movement into a word or two.

“Not bad, “he said. “My teenage daughter likes ‘Liberated Dames’ but that sounds like something from the Westminster Kennel Club. The Bugle isn’t really a dog and pony show.”

“Have you considered just plain ‘Bitch?’” I proposed deadpan.

Slade switched to a stern managerial manner. “Ryder, I must remind you that The Bugle is a family paper.We cover crime, government, wars and even sex, especially sex scandals involving powerful politicians and rich people, but we don’t like obscenities. Children read this paper and ‘bitch’ is over the line. You’ll be lucky to get ‘damn’ into your column.”

It was clear that this thin man would decide the name and probably the content of my new column. I could feel anger rising along with a deep desire to muss up his silvery Caesar haircut. While Slade droned on about deadlines (Wednesdays before 5 pm) and repeated the column length ( 750 words), I stared at my brightly colored movie poster on the wall opposite me. It was of the buxom comic actress Mae West starring in her classic 1933 film, “I’m no Angel,” the story of a girl from the wrong side of the tracks who finds success and love in the bawdy crime ridden world of burlesque.

In real life, West was a truly liberated woman who had defied convention early on the vaudeville circuit, fought censorship of her shows and movies during the Depression era and made a fortune. Some of her quotations, many of them double entendres, were collected in a slim paperback book, “The Wit And Wisdom of Mae West,” that I had picked up at a used book store on lower Broadway.

Pressing the phone receiver between my right ear and shoulder, I tuned out Slade and recalled a few shining moments in Los Angeles last summer when Mae West appeared in person during a crowded press conference called to publicize her role in the gender bending camp film, “Myra Breckenridge.” She was in her late 70s but still a statuesque presence who seemed poured into a sequined white evening gown. A white fox fur covered her bare arms.

She stood in the center of a stage, smiling seductively at the assembled print reporters and tv news crews who were hurling questions at her. I was one of them on assignment for The Los Angeles Free Press’ special feminist issue to mark the anniversary of women’s suffrage in 1920.

“What do you think of the women’s liberation movement?” I shouted over the din.

“I’m all for it,” she said into a microphone, her signature sultry voice clear and unwavering.

“In what way?” I yelled back.

“All the way,” Mae West drawled as the media assassins around me marveled in whispers how well preserved this old star was and wondering whether her flowing blonde hair was real or a wig.

Mae West knew the pitfalls of stardom and the glare of publicity. She once said, “There are no bad girls, just good girls found out.”

These were words to remember since Jason Slade seemed determined to have me found out to the world. “You have to get your picture taken before the launch of your column,” he said. “Contact the photo department right away. Take down this telephone number.”

I wrote down the number he gave me, but tried to talk Slade out of a promo that would introduce me to all manner of cops who were known to be devoted readers of the Daily Bugle.

“Can’t you hype the column with a cartoon image of Wonder Woman or the feminist symbol?” I asked him. “I want to maintain a low profile. It’s easier to get information that way.”

“You don’t strike me as the shy type, Ryder, “ Slade said. “But if you’re worried about strangers stalking you on the street, I’ll tell photo to shoot you in profile. Or you can wear a blonde wig and dark sunglasses. You’ll look almost as good as Gloria Steinem in her shades. Did you know that Steinem used to work for a CIA funded group?”

“Yeah, I heard about that part of Gloria’s glorious career,” I said. “And that’s a subject I might want to write about.”

“Go ahead,” Slade said. “I want investigative reporting. By the way, how’s that story on runaways in the East Village coming along? I can pay $500 for that if it works out as a cover story.”

“Coming along, boss,’” I said, “I’ll try to clean up some of the cuss words.”

“You have a bad ass exterior, Ryder, but you’re probably mush inside,” Slade said with a mirthless little chuckle. “I hope to see the story soon before one of those runaway girls gets killed or overdoses.”

***

By afternoon, the early winter sun cast a weak glow of light on the gaunt trees and storefronts along West 23rd Street. It would snow soon. I wrapped a long woolen scarf over my Navy surplus jacket and walked quickly out of the Chelsea enroute to the East Village. I had already interviewed Marshall Grodnik, Sean Collins’ lawyer, who had told me there would be a meeting of runaway girls around 4 pm at his social service agency, The New Way.

There was a sign discreetly announcing the place outside a low rise building on Second Avenue near St. Mark’s Place. There was no lock on the double glass doors and I walked right in. The tall rangy blonde I had already met in Tompkins Square Park was seated in a folding metal chair outside a closed office on the first floor. Her name was Denise and she seemed glad to see me again. The other runaway girls who straggled in eyed me warily.

When about a half a dozen teenagers showed up, a blonde social worker named Elsa appeared and opened up a conference room. After we took seats around a long table, she told the girls I was a reporter for the Daily Bugle and tried to assure them that my story wouldn’t reveal their real names. “ If you want to be in the story, just state your age and where you came from,” she said. “Give any name you want to.”

“No Name is a good enough name for me because I sure as hell don’t want my foster parents to find me,” said a freckled faced girl, age 15, a runaway from Massachusetts. “Not that my parents ever gave a damn. My foster mother once hit me over the head with a baseball bat. I’m not kidding.”

A 17-year-old girl with auburn hair grinned sardonically, revealing a chipped front tooth. “Your mother did that too? Listen, when I was a little kid, my mother used to stuff my head down the toilet bowl. She was an alcoholic.”

And so it went for 45 minutes as the girls exchanged stories of fleeing abusive familes, foster homes and juvenile detention centers, winding up in the East Village where some of them were introduced to life on the streets by pimps, junkies and psychopaths.

“Guys hassle you on the streets but I can run fast and last night, when this dude grabbed me outside my apartment building, I kicked him in the crotch,” said an 18-year-old brunette who identified herself as Jeanne “from Brooklyn.”

Jeanne conveyed an aura of glamour with her dramatic green eye shadow. She claimed she took a job “dancing naked” at a Greenwich Village theater after a stint as an uptown call girl turned violent. “I like it. It’s artistic,” she said.

“You seem to be together now,” observed Denise who looked almost wholesome in corduroy pants and a white cable knit sweater she said she had boosted from Macy’s.

“Not really,” said Jeanne. “Two weeks ago, I tried to kill myself.”

Jeanne, Denise and the other girls in the conference room were clearly different from middle class runaways, their more privileged predecessors in the East Village whose parents searched for them frantically among the crowds gathered for rock concerts and who put up pictures of their missing children in hippie run eateries, record stores and headshops.

Those kids had the option to return to their families any time. But the new runaways in the neighborhood had no such choices. They were throwaways as Sean Collins had said, fugitives like me, bouncing from place to place with no home in sight, lost souls whose stories told of the brutal downside of the American dream.

It was around 5 pm when a plump little girl with curly black hair spoke. She called herself Lily and said she had left her foster home in North Carolina more than a year ago, hitching rides to New York, sleeping on subways and hugging her portable radio, which was soon stolen, and her Steppenwolf records. Within a few weeks in the East Village, she said, men offering her places to stay had raped her.

“I think I’m pregnant,” she said, patting her stomach. “You know, it’s funny. I don’t like sex that much. It hurts me.” Lily looked around the room, her gaze stoic and unwavering. “Today is my birthday. I’m 14. I was living with this one guy for a week. He kicked me out today. But at least he said, ‘Happy Birthday’ when I left.”

On my way out of the conference room, I was nearly in tears and stumbled over a tall man sitting in the hall. He was reading a hardbound book with no cover, his long legs stretched out.

“Excuse me,” I said before realizing the man was Sean Collins.

Sean recognized me and said hello, explaining he was waiting to see Marshall Grodnik. “Why don’t you sit down for a minute.” he said, pointing to an empty folding chair. “What’s your hurry?”

His eyes were intense but kind. They seem to glow amber in the overhead light. Maybe I was falling in love, hallucinating as lovesick people do. I told Sean that the runaway girls had given me a good story and I needed to get back to my room at the Chelsea to write it up for my editor.

“You’re at the Chelsea Hotel now?” he asked, looking puzzled. “I bet that place has more drug dealers per square foot than my entire block on East Fourth Street. Are you living alone?”

I nodded, not mentioning I had a little gun to keep me company in case of emergencies.

“I hear The Chelsea is a really dangerous place to live,” Sean said. “So is the East Village. I always carry this.” Abruptly, he pulled out a pair of brass knuckles from the back pocket of his jeans, the first I had ever seen outside of photographs.

“Good God, where did you get those?” I asked him.

“They must come in handy on the street, but aren’t they illegal in most states?”

“Probably. I got these garbage picking,” Sean said. “You can find treasures in the trash.” He smiled roguishly. “Know anyone who wants to buy an elephant skin lamp?”

The man’s devil-may-care attitude was endearing. I asked him if he had found his book in the trash. He said it was the gift of an old friend and showed me the book, a worn collection of poems from English literature up to the 20th century. “One of my favorites, is The Highwayman, he said. “Would you like me to recite some of it to you?”

I nodded. The Highwayman by Alfred Noyes was one of my favorite poems too.

Sean Collins’ voice was as hypnotic as his deep set brown eyes. “And the highwayman came riding/riding, riding. The highwayman came riding up to the old inn door,” he began, and suddenly I was transported into another world, far away from old New York.

“Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard.

He tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and barred.

He whistled a tune to the window, and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.“

The door to Marshall Grodnik’s law office opened. Sean stopped reading me love poetry and stood up. “Gotta go,” he said. “Gotta get help suing my landlord for that kitchen fire I told you about.”

I blurted a Mae West one-liner. “Why don’t you come up and see me some time?”

“Maybe I’ll do that,” he said. This time his smile was rueful. “Just remember, I’m the kind of guy who goes out to get a quart of milk and doesn’t come back for three months.” Then he disappeared, a dashing married dude who suddenly seemed more elusive than a shadow.

Chapter 12

The next morning my story on the death threat against F.U. publisher Harvey Jewell was published in the Daily Bugle with a screaming headline: “ Radical Women’s Libbers Target Porn King for Execution.”

Richard, the British desk clerk on the Chelsea Hotel’s day shift, seemed impressed by the lurid coverage, which included an old photo of Jewell being carted off to jail in handcuffs on obscenity charges and an older picture of Valerie Solanes, the jailed “girl assassin” and author of the notorious anti-male SCUM Manifesto who had shot and nearly killed Andy Warhol” in 1968.

“Copy Cat shooter on the loose?” inquired the caption.

“Congratulations on your publishing coup, Ms.Ryder,” Richard said respectfully as I passed him on my way out of the hotel for morning coffee and a bagel at the corner automat. He held a cup of tea over his copy of the Daily Bugle, spread open on the desk, and pointed to a cardboard box not far from the hotel’s public pay home. There on a towel squirmed his calico cat’s new litter of kittens, most of them adorable tabbies who had just opened their eyes. I promised to take one after my first check from The Bugle came in.

When I returned to The Chelsea after breakfast, it was close to 9:30 and Richard wanted another word with me. “I have a tip for you but please keep my name out of any story you might do,’” he said, his voice lowering as a young couple, hand in hand, emerged from the left elevator to see the sights of the big city.

“Sure, Richard,” I said. “Shoot.”

Leaning over the desk, he told me he believed that Valerie Solanes had something to do with the death threat against Jewell. “Yes, I know she’s in a women’s prison in Westchester. But she could have dictated those words to a friend visiting her—an accomplice, maybe somebody who lives right here.”

Richard noted that Solanes, a panhandler and a prostitute, had never lived at the Chelsea Hotel but used to hang around in the lobby waiting to talk to guests like Maurice Girodias, who had published her SCUM Manifesto in his Olympia Press three months after she shot Warhol.

I was surprised to hear wild theories from Richard. He seemed so sedate. “Richard, I hope you’re not suggesting that a man like Maurice Girodias would write something so crazy as a death threat against a pornographer. This is a serious guy, an intellectual who opposes censorhship. He’s published banned literary masterpieces like Nabokov’s Lolita and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer.”

“Yes, I know all of that and I’m not accusing Girodias of anything,” Richard said evenly. “But there’s a young woman here, a graphic designer who writes on the side and I saw her talking to Valerie in the lobby a month so before the Warhol shooting. She calls herself Doria Nune. I think she’s a feminist and she may be in cahoots with Valerie.”

“How do you know that?” I said, getting fidgety with his finger pointing. “And so what if she’s a feminist? So what if she talked to Solanes? What does that prove?”

“Again, I must ask you not to quote me,” Richard said. “I’m just guessing, but I think Doria may be a prostitute like Valerie was. Not a street prostitute. Men come to her room and I think she goes on out calls from customers. I could be wrong but maybe you should talk to her.”

For a minute, I wondered if Richard was drunk.

“Why would this Doria Nune go after Jewell?” I asked him. “He’s all about prostitution. He advertises it in F.U. He gets arrested for promoting it.”

“Maybe Harvey Jewell did Doria wrong,” Richard said grimly. “Maybe she wants money. Maybe this could be what’s called a ‘shakedown.’”

Richard described Doria as a smart and pretty girl in her mid to late 20s with brown hair. “She dresses elegantly in velvets, suedes and soft leathers—much too expensive for what I’m guessing she makes from her design work.”

After swearing me to secrecy again, Richard gave me Doria’s room number and said that maybe I could “accidently” bump into her on the sixth floor. Or at the Spanish restaurant El Quijote next door to the Chelsea. “She drinks quite a bit,” he said. “She smokes, and has a sinus problem, due no doubt from too many cigarettes and snorting cocaine.”

Yes, Richard, a quiet man, was a fount of information and probably idle gossip. But back in my room, I made a note to check out Doria Nune. Then I went out again to buy a used copy of Valerie Solanes’ SCUM manifesto. Maybe it would keep my mind off Sean Collins.

***

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

So began Valerie Solanes’ shrewd, sometimes witty and violent anti-male screed, The SCUM manifesto. I finished reading it more than an hour before the next meeting of Media Women Ink.

If nothing else, Solanes was concise: “To call a man an animal is to flatter him; he’s a machine, a walking dildo,” she wrote.

Several lines showed the author’s interest in psychology and biology: ”The male is a biological accident: the Y (male) gene is an incomplete X (female) gene, that is, has an incomplete set of chromosomes. In other words, the male is an incomplete female, a walking abortion, aborted at the gene stage. To be male is to be deficient, emotionally limited; maleness is a deficiency disease and males are emotional cripples.”

This was a twist on the hoary old theory advanced by Sigmund Freud that women felt inferior to men because they suffered from penis envy. Solanes claimed the reverse: men, she said, were afflicted with “pussy envy.” While taking a crosstown bus on 79th Street, I wondered who among the well-heeled dames in Media Women Ink was capable of writing cutting edge street stuff like Solanes’ manifesto. Would any of them go to the trouble of slipping a death threat against Harvey Jewell under the grubby downtown door of F.U.? I raised those questions aloud once I got to Sasha Freed’s elegant upper east side apartment and salon.

“You can be damn sure it wasn’t me,” said Joy Brennan, who was among the first members of Media Women Ink to show up for the meeting. “I just want to put Jewell out of business. I don’t want to kill the creep. Besides, I’m not anti-male like Valerie Solanas. And I’m not gay either like she is.”

Joy was a few pounds lighter than she was when we first met. She carried a plastic bag of celery sticks and stayed away from the bowls of chocolate chip cookies set out on Sasha’s library table. She seemed to have a beef with me.

“I’m glad you got your story published in the Daily Bugle, but unfortunately it perpetuates the stereotype that all feminists are castrating bitches who hate men,” she said. “Personally, I think that death threat against Harvey Jewell was probably a publicity stunt he dreamed up himself to increase circulation at F.U.”

“No, I don’t think so, Joy, “ I said. “He really looked scared when I interviewed him. Noreen Turette was with me and she saw the threat on paper. Ask her.”

“I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if Noreen wrote it,” Joy said, biting into a carrot. She chewed reflectively and considered her nemesis. “But then, Noreen wouldn’t have the guts to do it. Also, she can’t write her way out of a paper bag. That’s why she does interviews.”

Sasha’s salon was beginning to fill up with stylish women arriving in twos and threes. A tiny wraith-like girl no more than 5 foot two inches tall came alone wearing an expensive black leather coat and leopard skin pill box hat. She removed her coat but kept on the hat. It sat like a crown on her head over a sensitive intelligent face framed by short brown hair. Her hazel eyes looked like they could assess a situation.

I nudged Joy, whispering: “Who’s that girl with the pill box hat? She looks familiar.”

“That’s Doria Nune. She was at the last meeting, don’t you remember?” Joy whispered back. “She said she went to dinner at Lutece with Harvey Jewell. She said she got a date with him through a personal ad in New York Magazine.”

“Isn’t she a romance novelist?” I asked.

“She’s also a graphic designer among other things,” Joy said. ” She used to work for Harper’s Bazaar and she lives at the Chelsea Hotel. She’s your neighbor.”

***

Sasha Freed called the meeting of Media Women Ink to order at around 7 pm. A lively discussion soon ensued about feminist publications and whether Helen Gurley Brown, editor in chief of Cosmopolitan magazine, was publishing trash or fodder for emancipated females on their way up in the world.

“Helen is is planning to have a male centerfold in Cosmo,” announced Noreen Turette who had arrived late to the gathering of feminist scribes. “My editor at Cosmo said she wants somebody well built and sexy like Burt Reynolds who’ll look good naked. Of course, he won’t be showing his penis. Helen draws the line on photographing dongs.”

“He can hang it out the window for all I care,” snorted Joy Brennan. “I think Helen Gurley Brown is not much different than Hugh Hefner—she tarts up models as sex objects to be exploited and sells them like she sells all the cosmetics advertised in her retrograde mag.”

Several members of Media Women Ink complained about the Cosmopolitan “style book,”saying it advised writers to insert the names of advertisers into their copy. Others ridiculed the magazine’s breathless prose, its exclamation points, italics and underlinings. Still more attacked “puff and fluff” articles dealing with the importance of wearing your false eyelashes to bed and the discreet art of adultery.

“There’s very little that’s feminist in Cosmo,”said Marjorie Nestle, the gray haired film professor and authority on gun molls in the movies. “It’s the old sexual sell. Helen Gurley Brown used to be an advertising copy writer. She knows how to market sex. But there’s not much other content in her pages worth talking about.”

Sasha Freed disagreed. “Oh, I think there’s more to Cosmo than sex,” she said. “It has a zillion articles and personal essays on how single girls feel being single and how to live alone and like it and how to navigate the dating scene and the job scene. I think Helen Gurley Brown is something of a pioneer. Yes, she’s mainly a businesswoman. But she’s made it acceptable for single women to have a career and a sex life and to talk openly about it. She’s a practical feminist.”

Sasha’s comments seemed to settle the matter. Then, suddenly, Doria Nune spoke, her voice raspy and cynical.

“Look, we live in a sexual world,” she said.“I think women need to be better educated about men and their equipment and we women need to know more about what arouses us sexually. There is no mainstream women’s magazine right now that does that in a straightforward way. Lots of men read Popular Mechanics. Why not a magazine for women that has information on the mechanics of getting great sex? A magazine that has articles on oral sex and how to get your guy to go down on you. I haven’t seen anything in Cosmo like that. Have you?”

Before anyone could answer Doria’s question, Sasha interceded. “Doria is a working on a start-up magazine, ladies,” she said. “It’s called Pink and it’s very progressive in concept. Do tell us about it, Doria darling.”

Doria didn’t hesitate. She said that Pink was a work in progress, a high quality slick magazine that would feature male centerfolds. “But they’ll be treated more like art objects than sex objects. And they’ll have real genitalia. Pink will also address lesbian sex. There will be a column called ‘The Sapphic Sister.’ We’ll have interviews with gay women.”

She paused and withdrew a kleenex from her handbag, dabbing her nose. She seemed to be having trouble breathing. With an effort, Doria continued her presentation. “Pink will have plenty of how-to advice on reaching an orgasm with or without a partner. And we plan on running the latest models of vibrators and various sex toys. We will be candid about masturbation.”

Some of the women in Media Women Ink looked intrigued. Ada Schwartz, the Village Voice writer who was working on a book about the politics of the vagina with an erotic artist who taught classes on masturbation, seemed positively thrilled. A few women were red faced, plainly embarrassed.

Joy Brennan just wanted to know more. “Doria, it sounds good, but some of this stuff you’re talking about—the centerfolds– is just soft-core porn,” she said. “I understand that your magazine will be more explicit than Cosmo. But aside from the articles on sex, how will it be different from Helen Gurley Brown’s magazine?”

“We’ll definitely be more avante garde than Cosmo, and we will make a difference in women’s consciousness,” Doria said. “We’ll have top notch art, photography, fashion, political cartoons, general interest articles, fiction. We’ll talk about role reversals, open marriages, men doing housework and child care.”

She dabbed her nose again. “By the way, I’m looking for people who want to write about women’s sexual fantasies. That will be a monthly feature. If you’re interested, call me.” Doria recited her telephone number twice and stopped talking. I got the impression she was exhausted. But maybe she didn’t want to answer any more questions. I wondered who were her investors and advertisers.

After the meeting, I introduced myself to her as a “sister inmate” at the Chelsea Hotel, and said I’d like to interview her for my new column at the Daily Bugle.

Doria seemed interested. “Call me tomorrow morning around 11:30,” she said with a wan smile. “That’s when I start waking up. We can chat over coffee in my room.”

CHAPTER 13

Around 10 am at The Chelsea, I was busy working on my story about the runaway girls in the East Village when Richard called my room from the front desk. “There’s a woman here who wants to see you,” he said. “Her name is Phoebe Whistlethorpe. She says you used to live with her.”

This was not good news. I told Richard to tell the lady that I’d be downstairs in a few minutes. Then I crumpled up several sheets of copy paper with my rough drafts and tossed them into the hotel’s wastepaper basket. The arrival of Phoebe was a reminder to me of the rules of Karma and the laws of the street: Your sins of omission and commission can rear up and grab you by the throat. There’s no such thing as a clean slate. What goes around comes around.

Quickly I washed my face and slipped into a pair of jeans and a sweat shirt to see my former roommate. I felt a twinge of guilt for having left Phoebe’s flat without telling her of my new lodgings. But the second I faced this woman in the lobby, she made it plain I had good reason to stay clear of her. Her once sunny disposition had disappeared. She was hopping mad.

“There you are—the apotheosis of the feminine mystique,” she said sarcastically, taking in my casual duds with a disapproving glare. “I remember when you went through a well dressed phase in California. But I suppose I shouldn’t expect even a touch of class now that you’re writingfor that fascist rag, the Daily Bugle.”

She sat beneath a huge papier mache angel hanging in the air by a wire from the ceiling of the lobby. At 38, Phoebe looked trim and itching for a fight. Her angular face, its features made vivid with pancake makeup and blood red lipstick, was a mask of hatred. I knew she habored an intense hatred for the man who had rejected her in Pasadena, the man she had expected to marry. Now I was getting my share of malice from her reservoir of rage.

All I could say to her was: “How did you find me, Phoebe?”

“I wasn’t looking,” she said. “But Marsha, the married woman upstairs in my building—remember her?—she reads The Bugle and she showed me your article the other day on Harvey Jewell. It’s garbage and I don’t believe a word of it. I called your editor at The Bugle, and told him I had mail for you. He gave me your telephone number. You forgot to make out a change of address form at the Post Office when you left my apartment in such a hurry. I’d do that today if I were you, because this is the last time I’ll be delivering letters for you. I never want to see you again. We have nothing in common.”

Phoebe dug into her black shoulder strap bag and handed me two letters. I barely glanced at them.

“Thanks, Phoebe,” I said. “I wrote you a note when I left and I don’t know why you’re making such a big deal out of my not telling you where I was going. I was planning to.”

“You could have called me,” she said. “I’m somebody who put you up with no questions asked, helped you get settled, introduced you to the neighborhood and let you have free reign of my apartment. I even cooked dinner for you a couple of times.”

Phoebe really knew how to push the guilt button. But she was right: I should have called her. I tried to come up with a plausible explanation other than my real fear at the time that she would blow my cover to the law with her constant chatter.

“It was nice of you to put me up and I appreciated it,” I said. “But I was mugged on your block when you were away and it seemed time to move on. I wasn’t thinking too clearly when I left and I didn’t know how long I’d stay at the Chelsea. I may be leaving soon.”

Phoebe laughed derisively. “Yes, you seem to have ants in your pants, don’t you? All this business about leaving L.A. because of your old hippie boyfriend and changing your name because of some other guy. You’re a very flighty girl. I told your editor you used to be called Joanna Willowby in California and you were no one he should depend on. He hung up on me, so this man must like you. Are you sleeping with him too?”

It was time to say adios again to this vindictive woman who had issues far deeper than my abrupt departure from her pad. “Please leave now,” I told her, eying the winged paper mache sculpture over her head. “Get the hell out of here or I’ll contact my friends in the Hells Angels to rearrange your face.”

I was just bluffing, but the Angels maintained a clubhouse in the East Village and I knew Phoebe was terrified of those biker boys.

Phoebe stood up, her body rigid with fury. “You’re nothing but an overgrown juvenile delinquent,” she said. “I know you shoplifted for food when you were living at my apartment and you still owe me for your share of the gas and electricity bills. And I think you stole from me. Some of my jewelry is missing. Maybe I’ll file a complaint with the police.” She walked out of the hotel, swinging her leather bag like a weapon.

I doubted she’d visit the cops in the 9th precinct. Phoebe feared and hated police more than the Hells Angels.

Richard had heard at least part of her tirade. “That is a crazy lady,” he said as I passed him on my way to the elevator. “She’s probably going through an early menopause.”

***

One of the letters Phoebe handed me came from Orange Man, my other former roommate now living in what he called a dome –a “hyperbolic parabola, to be precise”–on Venice beach. He enclosed a picture of himself standing in front of his dome, looking like a California surfer boy. His strawberry blond hair had grown longer.

“Hi there Joanna,” he wrote in red ink. “Bet your loving all the high energy in New York and avoiding the muggers and the narcs. I have a confession to make. You took my cherry. Yes, I was a virgin when we first had sex. You probably noticed I was inexperienced our first time, but were too cool to say anything. I was so ashamed that I couldn’t talk about it. But I want to thank you for introducing me to the joys of sex. You were so bold that I overcame my inhibitions. You can be sure I’m pretty picky these days when I choose new partners. You’re built like a brick shithouse, and nobody so far looks or feels like you….”

He continued in this effusive vein but I stopped reading. Now he tells me! I remembered his premature ejaculations but figured he had been smoking too much dope. It never occurred to me that a 28-year-old hippie male was a virgin. I had stereotyped him as a sensitive anti-war activist and writer, failing to see the obvious about his sexual identity when it was staring me in the face. Had I confronted this reality, I probably never would have left L.A. and gotten into deep trouble with Jed Scott on the road. I could have found another roommate to share expenses in Laurel Canyon. Instead, I ran away from my own hillside home and wound up in a pit of urban hell.

Men were such weasels, I muttered, tossing Orange Man’s letter into the wastepaper basket. Then I read the missive in a green envelope. It was from Maxwell Veribushi, my old West Coast comrade who had fled California on a murder rap. He had written me in black ink from Tel-Aviv.

“Dear Joanna, Because I’m moving around a lot, this will probably be my only letter to you this year. I hope you’re finding fulfilling work and true love on the East Coast. I’ve joined the Israeli army, penance for my sins. Dealing with violence every day here has changed my views. I’m becoming a pacifist. I don’t believe there should be wars anymore. But this conflict seems to have no end and I could be blown to bits tomorrow. I want you to know that I’m not running away again. I’ve stopped running. Israel is the end of the road for me.”

Like me, Max had killed a man and ended the comfortable life he had grown up with in America. I knew we would never see each other again. I started sobbing dry tears, my body heaving and doubled up against the scarred desk that the Chelsea Hotel had provided. Then I remembered what Max said when he gave me my little gun during both of our last days in L. A. “You’re an outlaw now. You gotta learn how to endure pain.”

So I returned to my story on the runaways of the East Village. I hadn’t lost everything. At least I still had work to do and people to meet. It was 10:30 in the morning and I would be having coffee with Doria Nune in an hour. She was a lot younger and more interesting than Phoebe and I doubted she’d talk about complaining to the cops if I failed to call her.

The phone rang again. This time Richard told me that a woman named Helene Switzer was on the line. “She says she’s Harvey Jewell’s secretary at F.U.”

“Oh Jesus, Richard, not now,” I said, remembering the middle aged woman with the big polished teeth in Jewell’s reception area at F.U. “I can’t handle another bitch trying to bite my head off.”

“You don’t know if she’ll do that,” Richard said. “Talk to her. Keep it strictly business.”

“Okay, you’re right, put her on,” I said grimacing. “Might as well get it over with.”

As it turned out, Helene Switzer couldn’t have been nicer. “Mr. Jewell was very pleased with your story on him in The Bugle, Ms. Ryder,” she said. “He’d like to talk you some more and hopes you will meet tomorrow for a late lunch at Serendipity. Can you make it at 1:30 or 2:00?”

I told Ms. Switzer that 1:30 was fine by me but would she please tell me a little bit about

Serendipity. I had heard the name mentioned but not much else.

“You must be from out of town,” Helene said. “Serendipity is famous for its foot long hotdogs and frozen hot chocolate. It’s close to Mr. Jewell’s townhouse and he loves this place. He’ll be working at home tomorrow, so it’s convenient for him to meet people there.”

“Oh,” I said, surprised by the porn king’s taste in his neighborhood’s restaurants. “What’s the address of Serendipity?”

“It’s on East 60th Street,but don’t you worry about getting there,” Helene said, her voice almost maternal. “We’ll be sending a car to pick you up at 1 o’clock.”

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.