Fritz Joubert Duquesne: Boer Avenger, German Spy, Munchausen Fantasist

“Col. Fritz du Quesne, a fugitive from justice, is wanted by His Majesty’s government for trial on the following charges: Murder on the high seas; the sinking and burning of British ships; the burning of military stores, warehouses, coaling stations, conspiracy, and the falsification of Admiralty documents.” He carried on hostile operations against the British government in various parts of the world under the following names: Fred, Fredericks, Capt. Claude Staughton, Col. Bezan, von Ricthofen, Piet Niacud, etc. His correct and full name is Fritz Joubert Marquis du Quesne. Prior to the war he was known as Capt. Fritz du Quesne, a big game hunter, author, explorer and lecturer.

-London Daily Mail, May 27, 1919

He is one of the most desperate and daring criminals we have ever had here.

His adventures read like a romance.

– Abraham I. Rorke, New York City Assistant District Attorney,

New York Evening Post, August 21, 1920.

On January 2, 1942, 33 members of a Nazi spy ring headed by Frederick Joubert Duquesne were sentenced to serve a total of over 300 years in prison. They were brought to justice after a lengthy espionage investigation by the FBI.

-Federal Bureau of Investigation, Duquesne Spy Ring, March 12, 1985

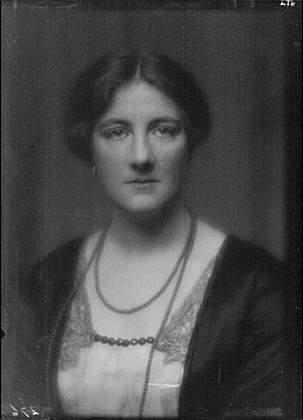

- Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne, Boar soldier, circa 1900

Leslie Evans

Frederick “Fritz” Joubert Duquesne (1877-1956) was a South African Boer who led an astonishing life on both sides of the law. Officer in the Boer army in the war with England, many times an escaped prisoner, pimp, newspaper reporter, foreign correspondent, novelist, spy and saboteur in South America where he blew up British ships during World War I, adviser on big game hunting to Theodore Roosevelt, publicist for Joseph Kennedy’s movie business. He feigned paralysis for five months to avoid deportation to England where he faced execution for the deaths of British seamen. And finally, he was the best known member of the largest Nazi spy ring broken up by the FBI during World War II.

Beyond his real exploits, Duquesne lived under some thirty aliases. He invented and reinvented his past at will, claiming to have been the greatest swordsman in Europe, attaching his ancestry to this or that aristocratic clan that momentarily appealed to him, granting himself military titles and medals, and producing endless accounts of battles, some of which he actually took part in. His most famous claim was to have guided a German submarine to sink the HMS Hampshire in 1916 at the height of World War I, killing Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, Britain’s Secretary of State for War and the head of Britain’s armed forces.

There are two biographies, one adulatory and one disparaging. Clement Wood’s 1932 The Man Who Killed Kitchener calls Duquesne “one of the bravest and noblest men who ever lived.” Art Ronnie’s 1995 Counterfeit Hero dismisses Duquesne for “four decades of spying, fraudulent activities, lunacy, and masquerading.” These wildly differing appraisals tell us at the outset that there is something more here than a cold-blooded German agent, a more interesting outsider.

The two biographies are very different in style as well as content. Ronnie’s is a conventional account, written more than sixty years after Wood’s. It carefully documents its sources with many footnotes and a bibliography. Wood’s book is long out of print and generally sells for $200 or better. I managed to get a copy in poor condition for $80. Wood met his subject only three times, not aware of who he really was until afterward. The first was in 1917 while Duquesne was living covertly in the United States after having escaped from a British prisoner of war camp in Bermuda. Always one for hiding in plain sight, Duquesne was disguised as a mythical Captain Claude Staughton of the West Australia Light Horse, a nonexistent regiment, and was on a national speaking tour across the United States promoting the American war effort. Wood was merely a member of the audience.

Wood spent an evening with Duquesne a decade later as part of a small group in Wood’s hotel room in Port au Prince, Haiti. Duquesne was introduced as Major Reginald Anson of the British army. Wood mentions seeing Anson once more, in Martinique in 1931, but gives no details. Wood passes over his sources evasively. In Port au Prince following the evening where “Reginald Anson” enraptured the company with his war stories, Wood is approached by “an elderly agent of a steamship line.” This unnamed man reveals that Major Anson is secretly Fritz Duquesne and turns over to Wood a large stack of documents and photographs that a friend is said to have collected with the intention of writing a book. The documents are never described further.

The book Wood writes is a fictionalized biography. He cites no sources, provides no index, and fills out what he says he knows about Duquesne with a steady stream of invented description and dialogue – how the birds were singing on a particular day, what people ate for dinner, which way Fritz looked while fording a river, chit-chat among soldiers, descriptions of scenes that come only from his own imagination. Though there was a real Fritz Duquesne and many of the incidents in The Man Who Killed Kitchener can be authenticated from other sources, the book itself I found to be mostly useful for seeing where Fritz, or perhaps Clement Wood, had stretched the truth.

A word on Wood and why he would be particularly sympathetic to Fritz Duquesne. The British fought two wars against the predominantly Dutch Boers in South Africa. The second, 1899-1902, was the most brutal. Discovery of gold and diamonds had led to a large influx of British citizens into South Africa, and a decision was made in London to forcibly dissolve the two small Boer states, the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State, and incorporate their territory into a larger British colony. The Boers put up a fierce resistance, including a prolonged guerrilla war. The British, led by Kitchener, who became commander of the British forces in South Africa in November 1900, initiated a scorched earth policy, burning farms and villages and driving Boer families into concentration camps, the first large-scale use of this device. Some 22,000 children and a smaller number of adults were starved to death in the camps.

While the majority in Britain supported the war, the left wing largely opposed it, on humanitarian grounds, particularly the Liberal Party and the Irish. Neither side paid much attention to the rights of Southern Africa’s black majority. Clement Wood was born in Alabama in 1888. He moved to Greenwich Village, became a socialist, served as secretary to Upton Sinclair, and was a supporter of Sacco and Vanzetti and Tom Mooney. As a militant opponent of British imperialism it is not surprising that he would view Fritz Duquesne as a kind of modern-day Scarlet Pimpernel. That framing of the Boer spy’s career would shift when the Germany he worked for against the hated English came under the control of Hitler’s Nazi Party.

Fritz in South Africa

Frederick Joubert Duquesne was of French Huguenot descent. Catholic France’s brutal wars of religion against the Protestant Huguenots had ended with the Edict of Nantes of 1598 granting legal rights to her Protestant subjects. The edict was repealed by Louis XIV in 1685 and the Huguenots were driven out of the country. Thousands set sail for South Africa in 1687, including many relatives of the French naval commander Abraham Marquis du Quesne. One of their descendants, Frederick L’Huguenot Joubert Duquenne (he changed the spelling to Duquesne in America in 1912), was born on December 21, 1877, in East London on the South African southeast coast. His father was Abraham Duquenne, his mother Minna Joubert. Fritz always claimed that his mother was the sister of the famous Piet Joubert, the Boer commander-in-chief in the second Boer War. Art Ronnie says that he can find no evidence of this connection.

Fritz soon had a younger brother and sister, Elsbet and Pedro. When the children were still young the family bought a farm in Nylstroom (today Modimolle) in the country’s far north. His father was a hunter and trader and often away, leaving the farm in the charge of Minna and Fritz’s old blind grand uncle Jan Duquenne.

At the age of twelve Fritz killed his first man. The main house had a room used as a trading post. One day while his father was away his mother began bartering with a Zulu customer, who attacked her when she would not meet his asking price for goods he wanted to sell. Fritz grabbed the man’s assegai spear and stabbed him in the stomach.

That same year a war party from a Bantu-speaking tribe attacked the area. Hearing of the impending assault, six families set off in ox-drawn wagons for the nearest settlement, at Sand River. Caught on the road, they drew the wagons into a square and fought a long gun battle with the raiders, even coming to hand-to-hand fighting. Twelve-year-old Fritz proved to be one of the best shots among them.

When he turned thirteen Fritz was sent to England for his education, where he spent the next four years. Clement Wood has it that after graduating, Fritz did a year at Oxford, then entered the prestigious Ecole Militaire in Brussels, and had a short stay at the French military academy St. Cyr. Wood says Fritz trained under the prominent fencing master Julian Mercks and became the champion swordsman of Europe. And that he fought eight duels, in three of which he killed his opponent. Art Ronnie says there is no record of Duquesne’s European championship, but that he was an excellent fencer and took part in many matches at the New York Adventurers Club.

Ronnie cites in contrast a 1913 letter from Fritz to Stephen Allen Reynolds in which he says that after his four years in England he was sent to Europe to study engineering, but on the ship met an embezzler named Christian de Vries and the two decided to take a trip around the world. Abraham Duquenne caught up with his son in Singapore six months later and gave him a good whipping. Ronnie suggests that Fritz spent the next three years bumming around Europe, returning home periodically to go on hunting parties. At the age of twenty-one in the summer of 1899 his father called him back to South Africa as the second Boer War was on the verge of breaking out. When he did return he spoke with an upper-class English accent.

Fritz was commissioned a lieutenant and assigned to commander Piet Joubert’s staff. He received a bullet through the shoulder in the battle of Lombard’s Kop in October 1899, where the Boers defeated the forces of Major General John French, who would later be commander-in-chief of Britain’s forces in France during World War I. Fritz was promoted to captain of artillery.

The first Duquesne legend arose in this period. By May 1900 the British were winning the positional warfare and taking the Boer capitals. The guerrilla war was just beginning. President Kruger, before going into exile, is supposed to have tried to ship a million or more pounds of gold and state documents to safety in Europe, dispatching thirty ox-drawn carts headed for the Lourenco Marques seaport in Mozambique. Enroute, Fritz is said to have met the caravan with credentials putting himself in charge. The four white soldiers assigned to the convoy tried to assassinate him and steal the gold. He killed them all. Then all of his native crew, after hiding the gold in caves near the Drakensberg Mountains, were killed by tribesmen. The gold was never recovered. The story persists, though no one can say whether it is true or not.

For a while Fritz led a small commando unit that blew up British trains and sniped at British soldiers. He was captured and escaped twice, once grabbing a guard’s pistol and killing him, the second time, with his hands tied, leaping off a bridge into a river. He became known as the Black Panther of the Veld. He fled to Swaziland, where he was captured. He was shipped to a prison in Lisbon the British were using for prisoners of war. There he seduced the jailer’s daughter and was soon on his way to Brussels, where he met the representative of the now defunct Transvaal Republic. He was sent to England, where he pretended to be a Boer defector. He volunteered for the British army, was given the rank of lieutenant, and sent back to South Africa. There he was assigned to a light cavalry unit.

He soon deserted and became a courier between the small isolated Boer commando units. He ran his own commando group, particularly harassing Kitchener’s scouts, led by Chief of Scouts, the American Frederick Russell Burnham. Burnham in his autobiography wrote, “there were only two men on the veld I feared, and one was Duquesne.” He added: “Much has been written about Duquesne, most of it rubbish. Yet his real accomplishments were so terrible and amazing that they make the yellow journal thrillers about him seem as mild as radio bedtime stories.” Each man was assigned by his superiors specifically to kill or capture the other.

While serving as a Boer courier Fritz was able to make his way to his family farm in Nylstroom.

There he found a scene of utter desolation. His house was burned to the ground. An elderly black servant told him that a party of British soldiers had gang raped and then shot his sister Elsbet. They hung blind old Uncle Jan. And they raped his mother, who was then taken to a concentration camp. He swore a lifelong oath to wage war against the English, and against General Kitchener, who he held personally responsible for the destruction of his family.

Fritz put his British uniform back on and went to the nearest camp, at Germiston east of Johannesburg. He found her there, starving, infected with syphilis, with a syphilitic infant in her arms. He swore he would make the English pay. He never saw her again. Leaving the camp he passed two captains. He shot them both dead.

Next he went to Capetown, arriving in October 1901. He was accepted as a British officer. He recruited twenty Boer sympathizers and made plans to plant bombs at power plants, munition dumps, rail yards, and bridges. He was personally to blow up the reservoir above the town, releasing a huge flood. Typically, the night set for the detonations Fritz put on his best dress uniform and attended a party for the governor of Cape Colony. One of his band turned traitor and Fritz and the eighteen others were arrested.

At their trial all were sentenced to be shot at dawn. That night Fritz was offered his life if he would reveal the Boer codes. He did so, claiming afterward that his version was deliberately inaccurate. The other eighteen were executed on schedule. In the Cape Castle prison, he spent months working with only a spoon to dig away the mortar holding the large stones of the wall in place. On the night he was to escape, he kicked out several loose stones and began to crawl through the hole when a cave-in pinned him to the ground. This made his jailers decide to ship him to a new British penal colony in Bermuda.

On shipboard, while at a stopover in the Azores, some of the prisoners were allowed on deck. Duquesne tried to escape, grabbing an inattentive guard’s rifle and beating him to death with it. He threw the body overboard, but other guards arrived and the chance to get ashore evaporated. As no observer would testify and there was some chance the missing guard had jumped ship, no charges were filed.

In Bermuda, the British had recently established prison colonies on a number of small islands off the coast of the main islands. The incorrigibles were sent to Tucker Island where they were handcuffed fourteen hours a day. There Fritz, while on a prison work detail, met Alice Wortley, daughter of an American businessman from Akron, Ohio, who was serving as Bermuda’s director of agriculture. They were drawn to each other and by a strange route met again later in the United States and married. Always ready to invent self-glorifying details, Duquesne told everyone, including Clement Wood, that Alice was from a long line of English aristocrats and that her father was the governor general of Bermuda. Wood’s book also contains one of Duquesne’s favorite fictions, that Alice helped him escape.

According to Ronnie, a guard promised Duquesne and several others aid in escaping. He unlocked their shackles, then shot the first man to go over the fence. It seems there was a reward for killing escapees. The survivors were transferred to Burt’s Island in Saint George’s Harbor. By this time the war in South Africa was over and the imprisoned Boers were offered repatriation, but on the condition that they sign an oath of allegiance to England. The irreconcilables refused and remained in prison.

On June 25, 1902, on a rainy night Fritz slipped past the wire fence and swam a mile and a half in shark infested waters to the mainland coast. He made it to the home of a Boer sympathizer, who gave him clothes and some money and sent him by boat to Hamilton, Bermuda’s diminutive capital, where he disappeared into the slums by the docks. There he teamed up with a black prostitute named Vera. She was paid 6 shillings a trick, and Fritz pocketed 3 of that for bringing her sailors. The arrangement lasted barely a week when he discovered that one of the clients he had picked up was a steward on the luxury yacht Margaret sailing in the morning for Baltimore. He got the man drunk, took his clothes, and staggered aboard the ship pretending to be drunk. His ruse was discovered the next morning, but by then they were at sea.

The captain swore he would turn Fritz over to immigration when they docked, so Fritz went over the side in Chesapeake Bay. He walked and rode freight cars to Paterson, New Jersey, where he had been told to contact a Boer sympathizer. Alice Wortley, having been informed of his destination by his benefactor in Bermuda, visited him there.

Twelve Years of Civilian Life in America

The Boer network sent Fritz to Manhattan, where, as an undocumented alien, he worked, first as a subway conductor and then as a bill collector the New York Herald. He regaled the staff with his adventure stories and was asked to write a few for the paper. This led in 1904 to a job as a reporter for the New York Sun. Two years later he was made Sunday editor. Between 1904 and 1909 he worked for three major New York newspapers and may have served as a foreign correspondent. He was written up in Men of America (1908), where he claimed that after arriving in New York he had been a war correspondent in Russia, Macedonia, and Morocco, and served in Paris on the staff of Le Petit Bleu. Elsewhere he also claimed to have toured the Congo Free State on behalf of the King of Belgium and gone to Australia where he said he took part in a 1904-1906 expedition headed by Sir Arthur Jones. And finally, he was said to have been in charge of building a string of theaters in the British West Indies for Alice Wortley’s father, S. S. Wortley. Duquesne certainly was a prominent reporter in New York, but Art Ronnie says he can find no evidence that any of these foreign adventures really happened. Fritz did write three novels, one published in Le Petit Bleu and the other two in South Africa.

In those years Duquesne was best known for his many articles on big game hunting in Africa. He was invited to the White House in January 1909 for a two-hour session with Theodore Roosevelt, who was preparing, as his second term ended, to embark on a two-year hunting expedition in Africa. Fritz was one of several such advisers but became well known on the lecture circuit after his presidential audience.

His next adventure was to team up with Frederick Russell Burnham, General Kitchener’s former Chief of Scouts. The two had been pledged to assassinate each other during the Boer War, but now they formed a company together to try to get Congress to authorize importing hippopotamuses into Louisiana’s swamps for their meat, and camels in the far west as draft animals. The country was in the throes of a severe meat shortage and the scheme was endorsed by Theodore Roosevelt and the New York Times. Duquesne on March 24, 1910, testified before the House of Representatives Committee on Agriculture in support of Representative Robert F. Broussard’s (D-Louisiana) bill H.R. 23261 which called for allocating $250,000 to investigate importing large African animals as a potential food source. A short Kindle book has just been published on this project, American Hippopotamus by Jon Mooallem. The Amazon description lauds it as “a historical saga too preposterous to be fiction.” The bill was never brought to the House floor.

In June 1910 Fritz Duquesne married Alice Wortley. They would remain together for nine years, during much of which Fritz was elsewhere. In 1912 he drove a van throughout New York State campaigning for Theodore Roosevelt running for president on the Bull Moose ticket. He published nominally true stories in Adventure magazine along with such authors as Sinclair Lewis, Talbot Mundy, H. Rider Haggard, John Buchan, and Rafael Sabatini. He was a founding member of the Adventurers Club, an association of about forty members limited to “adventurers, explorers, soldiers, travelers, filibusters, soldiers of fortune and other kindred spirits.”

In the summer of 1913, Roosevelt set out on a second expedition, this time to South America. Fritz cooked up some business deals to fiance a trip to follow, raising $5,000 from Goodyear Rubber to search for rubber plants and getting a contract with a small film company to make a documentary on the Roosevelt expedition. Neither of these ever came to anything. He and Alice left for South America in December 1913, taking $80,000 worth of film stock with them. Just before sailing Fritz became a naturalized American citizen. They were in Manaus, the capital of Brazil’s Amazonas state, when World War I broke out. Fritz sent Alice home and applied at the German consulate to become a spy. As a special incentive, his hated adversary Kitchener had been made Britain’s secretary of state for war.

Paid – modestly – by the Germans, Fritz Duquesne virtually disappeared, while around the ports of northern South America there appeared the actor Frederick Fredericks, a middle-aged Dutch botanist named George Fordham, and an old South African Boer named Piet Niacoud (phonetic of Duquesne spelled backward). These fellows drifted from Brazil to Dutch Guiana, Venezuela, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, everywhere with large crates of mineral samples or orchid bulbs to sent on outgoing British ships. Fritz later claimed that twenty-two of them sank, which Clement Wood repeated. Art Ronnie was more skeptical, but certainly some ships sank. Wood says that one of these crates weighed 80 kilos or 176 pounds. During this period Piet Niacoud was a popular figure in British circles in Brazil, making anti-German speeches and giving dramatic readings of literary works.

Already by June 1915 the British minister in Panama learned that Duquesne was working for German intelligence. One the places he was staying in a Brazilian port was surrounded by British agents but he escaped over the rooftops. Once he was captured while planting a bomb on a ship and while being rowed ashore in a smallboat leaped overboard. His last bombing was in February 1916, when he consigned what he claimed was his trunk of motion picture film and sixteen boxes of “minerals” to be shipped to the United States from Brazil on the British ship Tennyson. There was a large explosion and fire at sea halfway to Trinidad. The captain managed to beach the stricken ship but three sailors were killed. The British began a manhunt for Duquesne on a mandatory death sentence charge. British circles in Brazil were shocked to discover that Piet Niacoud was a German agent.

Fritz took off for Argentina, where he contracted with the national Board of Education to produce some educational films. He needed to get back to the United States to buy the film. To throw the British off the scent he faked his death, planting a story in the April 27, 1916, New York Times that he had been killed by hostile Indians while leading an expedition in Bolivia. The Times then ran a long obituary. Apparently he quickly reconsidered, likely because he only had an American passport, and under the Neutrality Act he would probably be immune to British prosecution. Seventeen days after the death notice he got a fake story onto the AP wire, saying he had been victorious in the Bolivian battle and had been rescued, badly wounded, by government troops. He arrived in New York uninjured in early May.

Who Killed Kitchener?

Now we are less than a month away from Duquesne’s greatest adventure, the assassination of British supreme military commander Sir Herbert Kitchener, on June 5, 1916. Duquesne’s version is certainly flamboyant. Kitchener was a larger than life character who played a dominant role in his age. He became famous as Kitchener of Khartoum when he led British forces in the Battle of Omdurman in 1898 that effectively reconquered the Sudan and avenged the death of Major-General Charles Gordon, who had been killed by the Mahdi’s troops in Khartoum in 1884. He was the ruthless commander in South Africa in the Second Boer War, was made commander-in-chief in British India in 1902, made Field Marshal in 1909, and British Consul-General of Egypt in 1911. He was appointed Secretary of State for War at the outbreak of World War I in late 1914. His famous likeness, with the flaring moustaches pointing at the viewer with the message “Wants You. Join Your Country’s Army! God Save the King,” was one of the lasting symbols of the British war effort.

Kitchener was among the first to see that the war would be a long one and British industry had to be mobilized on a war footing for a prolonged period. But by mid-1915, with the war stalemated in the trenches of France and astronomical casualties expended to win a few yards of territory, he began to lapse into silence at staff meetings and was more and more at loggerheads with the civilian government of Prime Minister Asquith. Finally the civilians decided to get him out of the way for a while by sending him on a mission to Russia, where there was fear that the Tsarist government would conclude a separate peace with Germany.

Kitchener departed for Petrograd on the HMS Hampshire on June 5, 1916, from Scapa Flow, base of the main British fleet, in the Orkney islands off the northeast tip of Scotland. At 7:30 pm during a violent storm the ship suffered a massive explosion and sank within fifteen minutes. The lifeboats could not be lowered in the storm. A few large rubber rafts were deployed but of those that made it to the coast they found a steep cliff the refugees could not ascend. Only 12 of the 655 persons on board survived.

Fritz Duquesne’s version of this story had the makings of a pulp thriller. He said that during the twelve days between the report of his death in Bolivia and his supposed rescue he went to the Netherlands, where a Boer Revolutionary Committee working with German intelligence gave him a commission as a colonel. The Germans had learned that a Russian nobleman, Count Boris Zakrevsky, had been assigned to go to England to accompany Kitchener’s party to Petrograd. The Count was kidnapped enroute by the Germans and his papers forwarded to the Boers with orders that Fritz Duquesne was to impersonate Zakrevsky and find a way to assassinate Kitchener.

Wood’s account has Fritz being fluent in Russian, which was not the case, though in Fritz’s telling Zakrevsky was supposed to speak good English. Fritz, dressed up as a Russian officer, is supposed to have met Kitchener in London, accompanied him and his entourage to Britain’s main naval base at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland, and sailed with Kitchener on the Hampshire. Fritz said he dropped self-igniting water torches out his porthole to identify Kitchener’s ship to waiting German U-boats. One of these fired the fatal torpedo. At the last minute Fritz leaped over the side into a raft in the raging storm and managed to navigate the hundred yards to the waiting submarine. He says he was then taken to Germany, where he was secretly awarded the Iron Cross as well as a medal from the Turkish government and made Baron of Brandenburg. Art Ronnie’s search uncovered no confirmation of these awards, but many German records were destroyed at the end of the war. During one of Fritz’s later arrests a photograph was found among his effects in which he is wearing the Iron Cross and medals from Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria. Art Ronnie is skeptical that these were really awarded and not purchased somewhere. Duquesne is supposed to have returned to the United States aboard the German submarine Deutschland, arriving in Baltimore on July 10, 1916.

The official British account had the Hampshire striking a mine laid that morning by the German submarine U-75 commanded by Curt Beitzen.

There were several other candidates for Kitchener’s death. Lord Alfred Douglas, ill-starred lover of Oscar Wilde, said the Jews did it, and that they bribed Winston Churchill as well to misrepresent events in the Battle of Jutland, which took place just before the sinking of the Hampshire, to the benefit of a New York Jewish financier. Churchill sued for libel and Lord Douglas served six months in prison.

Irish Republicans were said to have planted bombs in the hold. And General Ludendorff, joint head with Hindenburg of Germany’s armed forces in World War I, said it was Russian communists who gave the Germans Kitchener’s travel plans.

Fritz did appear in New York briefly, in May 1916, before the sinking of the Hampshire. Using the name Frederick Fredericks he bought $24,000 worth of film with the money he had been given in Argentina and stored it in a Brooklyn warehouse. Two weeks later the warehouse went up in a fiery explosion and the film was destroyed. Alice Wortley filed an insurance claim for $33,000 in Fredericks name with the company that held the policy. She also filed an $80,000 claim on behalf of “George Fordham” with another company, which had issued the policy on the film that had gone down on the Tennyson, the ship Duquesne himself had blown up!

Fritz was not seen again until July 1917, when he turned up in Washington, D.C. He moved on to New York, where he thought it best to become invisible, as usual by an exuberant public display of himself in disguise. World War I was at its height. The United States had entered the war in April. Fritz designed for himself the uniform of an imaginary Australian officer and, complete with swagger stick, presented himself at the offices of a national speakers’ bureau as Captain Claude Staughton of the also imaginary West Australia Light Horse. He claimed an amazing war record: Staughton had fought on the British side in the Boer War, in France and Flanders on the Continent early in World War I, then in the invasion of Gallipoli in the Turkish Dardanelles, not to mention New Guinea. Wounded many times, he was a veteran of every famous battle of the war America had just joined. He proved to be a sensation on a national speaking tour. He was even introduced to George H. Reid, former high commissioner of Australia, who did not suspect the impersonation. Captain Staughton even included some tips for the elucidation of his audiences on how the German spy system worked. A method actor, Duquesne for the time being put aside supporting the Germans and energetically sold American war bonds.

The defrauded insurance companies were still trying to find out who Frederick Fredericks and George Fordham were. They had a good idea it was Duquesne, as his wife Alice was the only identifiable figure involved in filing the insurance claims. And as one of these involved an arson explosion at a Brooklyn warehouse, it put Thomas P. Brophy, New York’s chief fire marshal, and Thomas J. Tunney, head of the Bomb Squad, which had just been co-opted into the military, on Duquesne’s trail. They got a lead when Captain Claude Staughton incautiously made a few pro-German comments to a women who reported him to the FBI. From a set of mug shots she identified Staughton as Duquesne. On December 7, 1917, detectives from the Bomb Squad raided Fritz’s Manhattan apartment and took him into custody. They found extensive newspaper clippings on all the ship bombings in South America, the invoice for the shipment aboard the Tennyson, and a letter of commendation from the Austrian high commissioner in Nicaragua.

Fritz was charged with two counts of insurance fraud, both following suspicious explosions. Britain filed for extradition for murder. Fritz’s first gambit was to feign insanity. He mussed his hair and began babbling. An insanity hearing was held in May 1918. There were two prominent psychiatrists, a prison doctor, a lawyer, and other officials in attendance. Fritz broke away from his guards and ran in screaming, “Bring up the guns! Bring up the guns! I want you men to watch the enemy!” Two of the medical men agreed the Duquesne was insane, the third that he had suffered a psychotic break but was recovering and partly faking. They all agreed that he could not be tried at that time. He was committed to Matteawan State Hospital for the Insane. Alice now divorced him.

He lasted there for five months, when he found his fellow inmates unbearable and suddenly had a complete recovery. He asked for a new hearing, where he pled guilty to attempting to defraud the Stuyvesant Insurance Company, the one with the policy on the Brooklyn warehouse. He did not plead on the other company, which involved the charge of blowing up the Tennyson. The British charges still had priority over mere insurance fraud, and a deportation hearing was held on December 23, 1918. In the middle of the proceedings Fritz collapsed, insisting that he was paralyzed from the waist down. Carried to prison on a stretcher he told the guards, “I don’t see why I should stay here long. There’s nothing can keep me here.”

Several doctors examined him. They stuck needles in his legs and under his toenails. Fritz never flinched. They finally agreed that he was really paralyzed. He was sent to the prison ward at Bellevue Hospital. Someone slipped him a pair of hacksaw blades, and for five months he spent his days in his wheelchair pretending to be bird watching while quietly sawing away at the heavy iron bars. A new hearing on May 19, 1919, approved his deportation to England. On the 26th just after midnight he broke out two window bars, fell to the ground from the second-story window, and staggered away into the night. No one helped him. He was scheduled to be sent to England to face murder charges later that morning.

This time he stayed at liberty for thirteen years. He sent a friend a press release saying that he had been rescued from Bellevue by his cousin, Count Francois de Rancogne, who had driven him to Mexico City. He actually went to Boston, where he started an advertising business under the name Frank de Trafford Craven. The New York police issued a wanted for murder poster for Duquesne. He later claimed that he briefly took a job as a Boston policeman during a police strike, which gave him a chance to destroy the file on him at Boston police headquarters. For years he regularly had friends from all over the world send postcards and telegrams to the New York police, reading “Come and get me,” signed Fritz.

In 1926 Fritz, as Frank de Trafford Craven, went to work for Joseph P. Kennedy, JFK’s wealthy father, who was getting into the silent movie business with a company called Film Booking Offices of America. As part of this job Fritz, daringly, moved back to Manhattan, where he was well known under his real name. In 1928 Kennedy along with David Sarnoff founded RKO pictures. Fritz Duquesne went along as part of the publicity staff.

In 1930 he switched to the Quigley Publishing Company, which put out a string of movie magazines. He gave himself a military title, and called himself Major Craven. He lived well, often told his war stories, including how he blew up English ships in South America during the Great War. On May 23, 1932, the Alien Squad caught up with him and he was arrested in the Quigley building. Fritz insisted he was Frank Craven and it was a case of mistaken identity. They took him away at gunpoint.

The Man Who Killed Kitchener had just been published, so the police called Clement Wood down to the station and showed him their prisoner. Wood, who had met Duquesne twice, in 1927 in Port au Prince, and just the year before in Martinique, insisted it was not Duquesne, but that he had known “Major Craven” for five years, that is, since 1927. This testimony could be seen as suspect.

Fritz was booked for homicide and for being an escaped prisoner. He was defended by Arthur Garfield Hays, who had been one of the attorneys for Sacco and Vanzetti, the Scottsboro Boys, and John Scopes in the famous Monkey Trial. By this time Britain did not want to pursue wartime crimes and withdrew the charges. He was rearrested on the escape charge, but a judge threw it out. Fritz Duquesne was a free man.

Fritz wearing the German Iron Cross, other medals from Germany, Austria, Turkey, and Bulgaria, circa 1930s.

Working for Germany Again

Fritz Duquesne, despite long periods when he was more a newspaperman or publicity agent, was at heart an adventurer and anti-British spy. In his youth that had meant working for Germany. It was a pattern that led to his final undoing. In the spring of 1934 he secretly accepted the job of intelligence officer for the Order of 76, an American pro-Nazi organization, which was then in merger negotiations with William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts. That October the secret was ferreted out by John Spivak, a writer for the left-wing New Masses. Spivak enlisted Duquesne’s Jewish then-girl friend to keep him informed on the spy’s activities. From here on Fritz’s career is beyond the cutoff date for Clement Wood’s adulatory biography. Art Ronnie gives no details of what Duquesne did as intelligence officer for this group, and Duquesne appears to have left them to take a job with the government’s Works Progress Administration in January 1935. In Ronnie’s opinion there is no indication that Duquesne held anti-Semitic views, but he saw the pro-German organizations as being anti-British. “Despite its ramifications, it was quite simply just a job to the amoral and opportunistic Fritz Duquesne.”

The American fascists were incompetent small fry. Fritz was soon to be drawn into the real thing. In 1935 Admiral Wilhelm Canaris became head of the Abwehr, Germany’s division of military intelligence. One of his goals was to establish a network of spies in the United States. He chose for this mission Colonel Nikolaus Ritter, a man who had lived in the United States for thirteen years, where he worked in weaving factories, and was married to an American woman. Ritter had returned to Germany in 1936, was assigned to the Abwehr the next year, and sent back to America in October 1937. Canaris instructed him to make contact with Fritz Duquesne, who he knew of from his work in South America in the last war.

Ritter traveled under his own name, but then went underground, using the name Alfred Landing. He made Germany’s most serious inroads into America’s secrets in meetings with other men before he got around to Duquesne. Ritter’s greatest coup was to get the plans for the Norden bombsight, in its day the most accurate device known for high altitude bombing. He got these from Hermann Lang, a naturalized German who had participated with Hitler in the Munich beer hall putsch of 1923 and now worked for the Carl L. Norden company.

Ritter hid the plans in the wooden casing for an umbrella and on January 9, 1938, personally handed the umbrella off to a German steward and secret courier on the ship Reliance bound for Bremen. Art Ronnie calls this “probably the single greatest espionage coup during that tenuous time before the war,” comparable only to the Americans breaking the German and Japanese codes.

The only other significant intelligence Ritter’s spy ring acquired came from Everett Minster Roeder, an engineer and designer at the Sperry Gyroscope Company. Art Ronnie lists Roeder’s thefts to include:

“[T]he blueprints of the complete radio instrumentation of the new Glenn Martin bomber and, among the Sperry developments, classified drawings of range finders, blind-flying instruments, a bank-and-turn indicator, a navigator compass, a wiring diagram of the Lockheed Hudson bomber, and diagrams of the Hudson gun mountings.”

Ritter had become friends with Fritz Duquesne back in 1931. They reconnected on December 3, 1937. Fritz was a few weeks short of his sixtieth birthday. Ritter enlisted him for his burgeoning network, giving him a check for $100. Fritz began gathering information to be forwarded to Germany.

Probably because of Fritz’s previous notoriety the Ritter operation, after its members were arrested, became known as the Duquesne spy ring. This was very far from the truth. From its inception at the end of 1937 Ritter’s agents in various American cities each acted alone, none, for security reasons, having information on any of the others. This changed when the Gestapo recruited German-born naturalized American citizen William Sebold, while he was on a visit to the homeland. They blackmailed Sebold into becoming a spy, using threats to his family and unearthing of an old police record in Germany that could endanger his American citizenship. They sent him back to the U.S. under the name Harry Sawyer to consolidate and expand the Ritter ring. He arrived in New York on February 8, 1940.

In retrospect it seems stupid of the Gestapo to entrust such a sensitive mission to an unwilling draftee. Sebold, before he even left Germany, on some pretext visited the American consulate in Cologne and told them the whole plan. When he arrived in the United States the first thing he did was contact the FBI, who actually had an agent move in with him for the first eight weeks.

Now Harry Sawyer set about meeting with the few existing agents whose names he began with. He was tasked with setting up a clandestine shortwave radio station to beam his discoveries to Hamburg. The FBI rented a house out on Long Island and set up a transmitter, staffed by German-speaking FBI agents. “Sawyer” told his pro-German confederates that he was himself the radio operator, and no one ever checked. The station transmitted heavily redacted versions of whatever the spies produced, leaving in enough genuine but harmless information to make the operation seem legitimate. Photographs and materials with tables and charts that could not be transmitted by Morse code were entrusted to shipboard couriers – cooks, seamen, and stewards. Harry Sawyer rented a two-room office in Manhattan. One of the rooms was soundproofed and used by the FBI to monitor a microphone bug and to run a 16 millimeter motion picture camera pointed through a one-way mirror.

Compared to the real damage done by Hermann Lang and Everett Roeder, Fritz Duquesne’s assignments seem like science fiction. The Abwehr sent with Sebold a microfiche listing eighteen tasks for him. He was to find out if AT&T had invented a secret ray to guide bombs to their targets; did the Army have a uniform that would repel mustard gas; did the U.S. have antiaircraft shells guided by electric eyes; had the U.S. developed a way to conduct bacteriological warfare from airplanes; did the U.S. Army have a trench crusher machine that could flatten a trench by driving over it. More prosaically Fritz was to tell the Germans if the United States military began large-scale mobilization – something they could read about in the newspapers. And they gave him a list of twenty-three aircraft and plane engine manufacturers from around the country and told him to get information on everything they produced. Fritz had by now promoted himself to Colonel Duquesne.

Fritz, to justify his pay, sent voluminous information through Sawyer, on flight training schools, sailing dates for ships going to England, the American defense establishment. The Abwehr responded, “Tell Duquesne that we are not interested in information that has been published several weeks ago in the New York Times and the Herald Tribune.” He wrote to the aircraft companies pretending to be a patriotic researcher, asking about their facilities and model line, forwarding to the Germans the stuff he got back in the mail. His one piece of valuable news was he somehow got hold of the information that Washington was releasing the plans for the Norden bomb sight to Britain. And he sometimes found out where Navy battle groups were headed. Except for Lang and Roeder, he was producing better stuff than most of the younger inexperienced agents.

Fritz, ever cautious, had met with Sawyer twenty times but always refused to come to the bugged office. Finally, on June 25, 1941, he agreed to a meeting there, where the FBI got him on film. Four days later the feds closed the net, rounding up nineteen German agents in New York and four in New Jersey. The total would run to thirty-three by the time they went to trial. It was billed by the press as “the greatest spy roundup in U.S. history.” Ninety-three FBI agents worked on the case. Fritz was taken in his apartment, by a man who had rented the unit downstairs and pretended to be a friend, who now showed up with two other FBI agents. J. Edgar Hoover branded Duquesne the “most important” of the defendants.

The initial twenty-four were tried as a group. Ten pled guilty, leaving fourteen to go to trial. Fritz was the first defendant to take the stand in the six-week trial that began that September. He mesmerized the jury and the audience with a dramatic and often fantastic recounting of his life story, from the days of the Boer War through his many escapes. He claimed he had been an observer for South Africa in the Russo-Japanese War and had spent ten months in a Brussels hospital for shell shock. He said he could visit Theodore Roosevelt in the White House any time he liked and had been there three or four times in one week. He retold how he had killed Field Marshall Kitchener and said he had been rescued from Bellevue Hospital by members of the Irish Republican Army. He denied, probably truthfully, that he had ever met any of the other defendants except Sebold. He said he thought Sebold was insane because he paid good money for junk, information Duquesne clipped from newspapers. “I sold him a code used by Benedict Arnold in the war between England and the United States in 1776.” Despite the presentation of voluminous evidence of materials he had supplied Sebold for transmission to Germany he insisted that he was not a spy.Fritz Duquesne at his trial, November-December 1941.

Unhappily for the defendants, their attorneys summations were scheduled to begin on December 8, 1941. Pearl Harbor took place the day before. The jury took only eight hours to reach verdicts on all twenty-four defendants. The sentences ranged from as little as fifteen months to eighteen years. Hermann Lang, purveyor of the Norden bombsight, and Fritz got eighteen years. Everett Roeder was one of four who received sixteen years. Most got between five and ten.

Colonel Nikolaus Ritter became the commander of a Luftwaffe Panzer division, then an American POW, and, after the war, a businessman in Hamburg. He died in 1974. Admiral Canaris, while running the Nazis’ principal military intelligence service, secretly plotted against Hitler, at one point proposing to have him declared insane and committed to an asylum. He opposed the Holocaust, recruited many Jews into the Abwehr solely to get them credentials that would get them to safety in Spain. He arranged for the escape of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Yosef Schneersohn from Warsaw, for which the Chabad movement has declared him a Righteous Gentile. He was executed by the Nazis just as the war was ending, for having connections to the attempt to assassinate Hitler.

William Sebold was provided with a new identity and started a chicken farm in California.

Fritz served the longest of any of the defendants. Hermann Lang was deported to Germany in September 1950. All but three of the others had completed their sentences or been paroled by 1950, and the last besides Fritz was freed in 1951. He served twelve years, seven months, and sixteen days, five years of which were in solitary confinement. In his last months in jail he filed one last appeal, claiming that when the FBI had arrested him they had seized a bag of uncut diamonds worth $3 million, and the map to the long-hidden Kruger gold. He was released on September 19, 1954; he was seventy-seven. His health had deteriorated greatly. He fell frequently, was partly deaf, had a dislocated shoulder that was not treated and set badly, and was thought to have dementia. He had had a stroke that left him partly paralyzed. He returned to New York, where a few old friends met him. The city’s Welfare Department placed him in a nursing home.

On December 21, 1955, he was welcomed back to the Adventurers Club for a dinner and talk at the Hotel Delmonico. Some members refused to attend, denouncing him as a traitor, but others wanted to hear one of the last of the founders. His famous voice was almost gone but he regaled them with the old stories, real and imaginary, the Boer War, his escape from Bermuda, Captain Claude Staughton, sabotage in South America, how he killed Kitchener, and his long years in prison. He died of a stroke on May 24, 1956, at the age of seventy-eight.

Hero, fool, madman, villain. He was all of these.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.