Exit From Eden: More Of Mary Reinholz’s Upcoming Novel

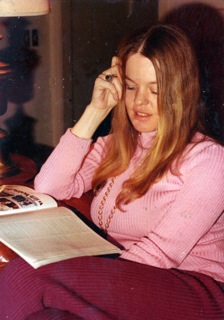

Mary in New York, early ’70s, on top;

the lower picture shows her near the end of the ’70s

CHAPTER FOUR

Junkie town. That’s how a neighborhood in the East Village struck me when I first arrived in New York, swiftly discarding my carefree California ways to survive the spaced out speed freaks, pill poppers and heroin addicts who prowled like the walking dead around this dirty bastion of flower power, so often compared to San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury district.

Here I was, a former west coast golden girl who only a short time ago had driven a convertible through the Hollywood hills, listening to the Beatles and The Beach Boys in wooded rich hippie enclaves, now reduced to a reed thin fugitive hungry for money and connections, stamping through dirty streets littered with condoms, used hypodermic needles, dog shit.

“Be sure you have enough cash on you to give the junkies if they stop you—don’t fight them,” warned my hostess Phoebe Whistlethorpe, a one-time WASP princess who was putting me up at her railroad flat overlooking Tompkins Square Park where the addicts frequently gathered for drug buys. “You can get killed that way.”

She had already shown me how to navigate the subway system, referring to it as the ten circles of hell. Now she recounted how her Marxist landlord had been held up twice and once stomped in the stomach on Avenue A when he endeavored to explain to a couple of Puerto Rican muggers that he understood their rage because they were the victims of class struggle and racism.

Phoebe figured I had been mugged upon my arrival in Manhattan, believing my fib that a “crazy man” high on smack at the Port Authority bus terminal had thrown a punch at me and caused my bruised jaw. I hadn’t told her much about my name change and the fact that I had become another person made insane by circumstance and my own demons. And since Phoebe was a talkative type, she didn’t need to know about the bloody passing of Jed Scott in Arkansas or my carefully concealed unlicensed .22 caliber pistol.

Some of Phoebe’s tips made sense, but I had no intention of giving what little money I had left to junkies. Instead, I adopted a grim “don’t mess with me” expression while checking out my roommate’s drug ravished turf. I would walk purposefully past groups of Latino gang members on Avenues B and C, alert to the rhythms of the street, learning quickly how to sense if someone was following me. It was like developing an primitive telegraph system.

But I let down my guard on an overcast afternoon after getting a clean bill of health from a Japanese male gynecologist who had examined me at the Margaret Sanger Clinic in a westside Chelsea neighborhood. “You clean as a whistle down there,” he said, reading the results of my blood and urine tests from the week before. “ No venereal disease, not pregnant.”

Happiness. I was in a fairly good mood when I left the clinic with a birth control prescription and headed east back to Phoebe’s apartment, my natural paranoia put on hold. A mistake. At some point in my walk I had regressed into California dreaming and longings for my neon-lit paradise lost, not realizing that an Hispanic kid, switchblade thin, had been shadowing me.

Silent in his sneakers, he entered the vestibule of Phoebe’s building as I stood there opening the mailbox we shared. In an instant, the lad thrust a butcher knife at my throat, rasping, “Gimme your money or I’ll kill you.” He certainly got to the point.

Oddly, I wasn’t afraid of him in that moment. In fact, I felt a strong empathy for this kid, another desperate soul on the streets of the Lower East Side who was willing to kill for survival–and the feeding of his habit. Maybe I felt like his mom. He couldn’t have been more than 16, 17 years old, a handsome teenager with a haunted heart-shaped face. Was I attracted to another bad boy? Or was this God’s punishment for my knifing Jed on the road after he raped and tried to strangle me?

As if in a trance, I began picking through the contents of my tote bag. “Can I keep my keys?” I asked the mugger, looking deeply into his eyes.

“Hurry up,” he said impatiently, his gaze now flashing fear, his blade moving to my chest.

Slowly, I extended a $5 bill from my wallet and he grabbed it. “Don’t follow me or you’’re dead,” he said, and bolted out the door.

I waited for a few seconds and then ran outside to get a better look at him, to remember him. He sprinted down East 10th Street, turned a corner on Avenue B and vanished. Back in the vestibule, I froze as terror finally overcame me for the first time in a city where it was not so easy to be invisible, especially if you were a girl alone in a drug bazaar. Hands shaking, I grabbed the mail and opened the second door to the building with my keys. It was a beautiful old townhouse that the Marxist landlord admitted he had bought for a song in an Eastern European immigrant neighborhood mixed with academics and artists. He admitted the newcomers were ruining his property values.

* * *

Holding on to a railing for support, I made my way up the flight of carpeted stairs to Phoebe’s double locked second floor apartment. There was no one at home. She was away on one of her business trips trying to develop a marketing plan for her line of artful products for the home. Her latest creations were bread sculptures that she baked in her tiny kitchen and laid out for decorating on a table in the dining area.

Switching on the track lights, I noticed Phoebe had filled a tray with a batch of doughy girl cherubs with bare bosoms and angel wings cooked and hardened to perfection. They all had smiling faces, bright blue dots for eyes and glitter on the nipples, ready to be hung in a bedroom or living room. Phoebe had left a note telling me to be sure and water the house plants, adding that she wouldn’t be back for a few days because she was staying with her cousin in Connecticut, an investor in her business.

This news didn’t ease my panic and the awareness of how vulnerable I was, too afraid to call the police or the landlord who might ask too many questions. I was sorry Phoebe wouldn’t be around for at least 48 hours even though she often made me uncomfortable. She was 10 years older, an intense domineering babe with a cute figure, a mane of chestnut hair and bitter memories of a man she called “Harold Shit,” who had jilted her a few years earlier in Pasadena where we had first met at a museum where she was teaching art. She was sympathetic when my marriage ended,and I appreciated her hospitality in New York. She was at least someone to talk to.

Now, the dead silence in Phoebe’s flat only added to the fear that had gripped me after my encounter with the kid mugger. I didn’t want to be alone here and was relieved at the prospect of attending my first meeting that night of Media Women Ink, the feminist writers group that Zenia Smith had told me to contact for connections in New York publishing. I was also glad that my .22, snug in its case, was well hidden in a space set apart in the living room with one of Phoebe’s brightly decorated room dividers. I checked my little gun, stroking the muzzle’s hard metal. It felt good.

***

The Media Women’s meeting was at 7 pm on the ritzy Upper East Side and I had several hours to prepare, first taking a relaxing bubble bath. I soaked for about a half hour in the antique claw-footed tub, flipping through the pages of several underground newspapers she kept in a rack nearby, among them the East Village Other, Rat– which covered the Columbia University Strike against the war in Vietnam– and a collection of pamphlets on women’s health and sexuality put together by a Boston women’s health collective.

Soon I discovered that Phoebe’s bathroom reading also included an outrageous sex tabloid called F.U. published by a pornographer named Harvey Jewell who offered hipster humor wedged between centerfolds of naked men and women with gaping genitalia. Semen was the topic of many jokes and much word play.

“Freeze it and Squeeze it,” counseled a sex advice column for women who wanted a kinkier kind of facial. Otherwise, the weekly was about as erotic as closeups of chopped liver at the Second Avenue deli. One of the inside pages featured a drawing of lesbian nudes having at it with Sapphic lip love and the words, “Sisterhood feels good!”

It all seemed like a school boy’s goof. There was a “Dick List” in the back pages, showing a head shot of President Richard Nixon smiling maniacally in the middle of a dart board and a picture supposedly of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’ pudenta with a headline blaring: “Million Dollar Muff!!” New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller were shown with pictures of enormous hard-ons superimposed on the crotches of their trousers.

The front page featured a column by Jewell with a photo of him grinning roguishly and giving the finger to the world. His writing for this issue was an angry rant attacking ” phony women’s libbers for their failure to understand “their own sexual needs.” Jewell then characterized the movement as elitist and “lilly white” run by high falutin feminist authors from the Seven Sister colleges.

“Have you noticed most of these women’s lib leaders are fancy Ivy League writers like Betty Friedan and this Gloria Steinem babe who posed as a Playboy bunny to advance her career? These are frustrated women who want big book contracts and a chance to mouth off about how oppressed they are on television. Where are the secretaries, hairdressers and factory workers for this fake movement?” Jewell asked rhetorically.

This was not the usual sexist spiel from men opposed to the women’s movement. There was energy and conviction in Jewell’s tirade. It seemed strange that Phoebe, who had joined many leftist crusade in California and insisted she was a feminist, would read F.U. even in her bathroom. Then it hit me: She might be thinking of placing an ad in this skin rag for her sexy bread sculptures and a new line of erotic pillows with stitching based on sexual positions in the Kama Sutra. I turned to the ads in F.U. Many were for sex aides, escort services, massage parlors and strip joints in Times Square.

There were also classified ads for employment, including a prominent one, framed in red ink, announcing an opening for “an associate editor” at F.U. ”Applicants must have a college degree, good grammar and an understanding of the adult industry,” the ad read. “English or Journalism majors preferred. Sense of humor and open mind required. Salary negotiable.”

God knows I could use a full time job after several weeks of scrounging for temp work, usually clerical gigs that paid cash under the table. At this low point in my outlaw journey, even F.U. was beginning to look good.

Feeling less traumatized as the afternoon wore on, I rifled through Phoebe’s closet for some decent duds to wear for the meeting of the feminist literati. Phoebe was shorter and a little thinner than me but the fake fur jacket her mother had sent her from San Francisco fit well over her velvet bellbottoms and a yellow satin blouse I had lifted from Lord & Taylor for a job interview. I even put on a little lipstick and blush from the well stocked cosmetics shelf in her bathroom.

It was definitely time for new beginnings. I called up Zenia Smith long distance at her law office in Washington D.C.

“Baby doll, ” she murmured when I announced myself. Her tone was cordial but her words were hardly comforting. “I have news, some good, some bad. The cops in Oklahoma now think the motel thing might be an inside job but I’ve heard the Feds may get involved because of a tip they got in Nashville. Do you know a woman named Thea Resnikoff? ”

Panic resumed. Zenia had sources in and out of law enforcement, and this news was definitely not good. Thea Resnikoff–the hip hairdresser who had drugged and ripped me off for more than $2,000 in cash before I swiped three one hundred dollar bills from her hair salon’s cash register, must have decided to exact revenge by calling the FBI. She had supplied the Feds with Zenia’s California license plate number, but Zenia said she told them her car had been stolen from her former home in the Crenshaw district.

Now Zenia offered her usual bracing counsel. “You’re not out of the woods yet, but don’t forget who you are, a gutsy little girl reporter,” she said. “You are Cassandra Ryder. Play the stereotype of a seasoned lady journalist. Dress the part. Get yourself a what the hell hat, a fedora. If you don’t feel confident, fake it. Being scared is so pathetic.”

CHAPTER FIVE

Sasha Freed, a literary agent in her mid 40s, was hosting the meeting of Media Women Ink. She greeted me at the door of her apartment and salon on East 78th Street near Madison Ave, a chic bohemian presence in sandals, black trousers and a matching black tunic. A simple solid gold pendent hung from a chain around her neck. She held a dark Gauloise cigarette.

We hit it off right away, partly because Sasha had warm memories of Zenia Smith whose name I quickly dropped.

“Zenia is a great character,” Sasha said as we stood in her entry hall chatting. “I’d love to get a book out of her because it would read like comic novel. I remember when she organized a ‘pee-in’at Harvard to protest the lack of toilet facilities for the few female students there. The Harvard Crimson had a heyday with the story.”

Only a couple of other well-coiffed women were in Sasha’s digs, inspecting her collection of African masks and art books by clients. Neither of them looked like the type who would harbor a fugitive. A light rain had been falling when I got off the Lexington Avenue subway line near her place and I asked Sasha if she expected many people tonight.

“Oh yes, she said. “We have some dedicated regulars. Tonight you’re likely to meet Joy Brennan, a plump young woman who graduated from Sarah Lawrence but says she can only get clerical work because of her weight. She sat in at the Ladies Home Journal protest. You probably heard of that action in California: 100 feminists invaded the magazine last March, took over the office of the executive editor John Carter Mack for 11 hours and demanded that he, unh, remove himself and hire a woman to run things.”

Sasha took a drag from her cigarette, inhaling deeply and expounded on how the feminists had laid siege to one of the most respected women’s magazines in America. “Susan Brownmiller, who used to work for Newsweek, was at this action. She’s researching a big book on rape.”

As we awaited arrivals, I told Sasha a little bit about my background in journalism, mainly as a reporter for dailies, explaining I was hoping to meet women working at newspapers and magazines who could recommend good editors to contact in New York. I knew only one or two.

Sasha lit up another Gauloise. “We have quite a few pros,” she said. “There’s Noreen Turette, who interviews celebrities for the slick magazines, among them Playboy because she says it pays well. Marjorie Nestle is a film professor who just wrote a piece for the New York Times about really good gun molls in the movies and she has several contacts at that august rag.”

She blew out a couple of smoke rings. Sasha had a faint English accent, the result, she confided, of living in Britain as an adolescent after her father, once a successful screen writer, was blacklisted during the heyday of the Communist hunting McCarthy era. I had the feeling that Sasha’s last name was a pseudonym and felt a kinship with her. She was hardly a doctrinaire feminist and seemed to look at the scene in her salon ironic detachment.

“You might get a kick out of Ada Schwartz, a medical writer for The Village Voice who is working on a book about what she calls ‘the politics of the vagina,’” Sasha continued with a small wry smile. “She has photos of various vaginas, showing how they’re so wonderfully different in shape and color. Ada is co-authoring her book with Jan Goode, a feminist erotic artist who also runs classes teaching women how to masturbate. Apparently Jan believes you meet the best people that way and you never have to leave the house. Not my cup of tea, but this is definitely a diverse bunch of dames.”

“Charming,” I said, stifling a laugh.

***

By 7:30 that evening about a dozen women had gathered in Sasha’s living room, seated on straight backed chairs and a leather sofa. Some of them were dressed modishly in midi-skirts and Gucci shoes. Others affected the George Sand avant gard literary look with pant suits and men’s shirts.They nibbled on finger food Sasha had set out and sipped coffee from china cups. They seemed to live in a rarified world. There were jokes about Cosmopolitan editor in chief Helen Gurley Brown, author of the best seller “Sex and the Single Girl, who transformed her magazine in a primer on how to catch a man by such strategies as leaving cigar butts behind in ash trays to induce jealousy in a suitor.

One of the most striking women there was Noreen Turette, the magazine writer Sasha had mentioned. She looked like a Cosmo girl with her platinum blonde hair in a pixie cut reminiscent of Mia Farrow’sm her suede mini-skirt and thigh high boots over her black tights. Her mink coat was draped casually over an empty chair.

Noreen caught my attention when began speaking in aggrieved tones about a “pudgy little man ” who had wronged her. Soon it became clear that she meant pornographer Harvey Jewell, the publisher of F.U.

Noreen said was planning to sue Jewell for invasion of privacy and breach of contract because he had printed her name and telephone number in a recent issue without her knowledge or consent. “He wrecked my life for the past week,” she said.“Jewell also published a picture of me in his disgusting ‘dick list” with my face stuffed in a picture of a toilet bowl. All because I didn’t want my name used in a story he published about New York bachelor millionaires and their tastes in women. Jewell thinks writers should be proud to write for F.U. I’m sure not, but freelance writers are like itinerant grape pickers and sometimes you just have to take what you can get. I’m hoping my lawyer will get Harvey Jewell to shake the money tree and settle.”

Noreen’s story hit a nerve with me in my state of penury, but several of the sisters in Media Women Ink appeared to be outraged by her story.

“Sweet baby Jesus!” exclaimed Marjorie Nestle, a graying academic in a floral peasant dress and pale pink granny glasses. “Noreen, why would you, a feminist, even consider being published in that vile porno rag? Yes, I know Germaine Greer wrote something on women’s sexuality for F.U., but she’s a little crazy and likes smut. I think she’s put her brains in her brassiere.”

“Henry Miller likes F.U., and thinks it’s a cosmic joke,” somebody else from Media Women Ink. said. “Of course, he’s a sexist–almost as bad as Norman Mailer,” she went on, naming two of my favorite authors.

“I couldn’t publish my article anywhere else,” admitted Noreen, crossing her legs and looking a little guilty. Her darting blue eyes roved the room for support. “I need every cent I can get because I’m getting a divorce. And my husband Stanley doesn’t want to give me much alimony because I have a career and we don’t have kids.”

There was a murmur of concern from a few members of the group with this revelation, and a look of disgust from an overweight natural blonde packed in khaki pants whom I guessed was Joy Brennan.

She rose from her chair. “Pornography is violence against women!” she shouted. “It’s criminal and Harvey Jewell is just a pimp with a printing press and Mafia distributors. He should be in jail. Noreen, you prostituted yourself by doing business with him. Did you have to kiss his dick?”

“Oh shut up, Joy,” snapped Noreen. “You’re just jealous because you can’t get a date or a job in publishing. And you must be living in a convent because Harvey Jewell is regularly carted off to jail for obscenity and promoting prostitution. And every time he gets himself arrested, the circulation at F.U. goes up. He gets all this publicity and it only helps his claim that he’s a martyr for free speech, Mr. First Amendment.”

“Some martyr,” piped up a petite brunette in fringed buckskins who claimed to be a romance novelist. “He’s loaded. I once dated Harvey Jewell after he answered my personal ad in New York magazine. He picked me up in a chauffeur driven limo and we went to Lutece for dinner. He can be very sweet, like a Jewish teddy bear. But I don’t like his line of work, just his taste in restaurants. He really prefers food to sex.”

Joy Brennan’s look of disgust deepened. “Who cares what he prefers?” she said. “Media Women Ink should take a stand and organize a demonstration calling on the police to shut his sheet down and arrest him and his mobster buddies. And if you don’t like that idea, Noreen, why don’t you pay a visit to Harvey Jewell and make it all better between you two. Wear your favorite push up bra and give him a quickie.”

Noreen gave Joy the finger, gathered up her mink coat and stormed out of the room.

Throughout this heated exchange, Sasha Freed remained silent. Now she stood and spoke firmly. “Ladies, can we keep it civil? We are here to come up with practical suggestions on how to succeed in the male dominated world of publishing and I have an announcement to make. The Daily Bugle, which has the largest Sunday circulation in New York, is looking for a freelance columnist to write about the women’s liberation movement for its weekly magazine. Not much money in it, but if anyone is interested, please speak to me after the meeting.”

Grumblings ensued. “The Daily Bugle is fishwrap, not much better than F.U.,” said Joy. “Always running these inane pictures of Australian bathing beauties from ‘down under” to pander to their working class male readers. It’s a cartoon.”

“You’re right, Joy,” said Ada Schwartz, author of the budding vagina book who described herself as a card carrying member of the American Civil Liberties Union. “But who of us is perfect? The Village Voice publishes sex ads to stay afloat and I bet you want to put them out of business too. You gotta be careful about going down censorship alley. The feminist press shows vaginas too.”

It was a sobering thought. But when Media Women Ink finished its formal business, discussing a recruitment drive and an awards dinner for publications sensitive to feminist concerns, I was the only applicant looking for more information about the Daily Bugle opening.

As several members lingered over glasses of sherry, Sasha beckoned me into her office and produced a business card for Joy Brennan—“She has a ton of contacts”—and another for Jason Slade, the Bugle’s Sunday magazine editor.

“Jason is an import from the Chicago Tribune—and a very smart literate fellow,” she said. “If you get this gig or do other work for him, you should scout out a rumor about the FBI and the feminists.” Her voice dropped to a near whisper. “I’ve heard there are female agents who have infiltrated the New York City chapter of the National Organization for Women looking for fugitives from the Weather Underground.”

The possibility of government spies working their way into NOW, Betty Friedan’s mainstream women’s rights organization, sent a fresh tremor of fear up my spine as I walked hurriedly from Sasha’s apartment. Three members of the militant anti-war Weather Underground had died nine months earlier when the nail bomb they were making in a Greenwich Village townhouse exploded. Two other members, Cathy Wilkerson and Kathy Boudin, had escaped.

Where were they now? Maybe one of them was in Media Women Ink. After all, I was a sister criminal at large who had wormed my way into an upper crust feminist writers group, so anything was possible.

I shuddered in the night chill and wondered if I would ever find a way home again—or any safe place. The light rain was becoming a downpour and I ran towards the nearest subway entrance.

CHAPTER SIX

The next morning, over breakfast at a cheap soul food joint called Eggs and Grits on Avenue C, I scanned the Daily Bugle and found it a concise and irreverent rag. Lots of blaring headlines about the budget crisis, the drug trade, married local pols in “love nests” with beautiful mistresses and an editorial calling for reviving the electric chair to dispatch cop killers. “Dust off old Sparky!”.I chuckled. The tabloid was like a parody of yellow journalism from 1930s. Its Sunday magazine probably paid more than the daily for features and maybe I could interest Jason Slade in my writing some longer pieces for him if he didn’t pick me for the columnist gig.

Already I had my eye on the runaway kids I’d see camping out in Tompkins Square Park, sometimes sleeping alongside winos and homeless men next to trash can fires to keep warm at night. It could be a big story. Where did they come from? How did they survive as fugitives like me? They were pictured in some media accounts as the disaffected children of wealthy parents, but the boys and girls I was spotting seemed rougher and tougher than their privileged peers who attended concerts at Fillmore East on St. Mark’s Place. Some of the girls were tomboys, dressed in jeans, cowboy boots and heavy Navy surplus jackets.The scruffy long haired boys were similarly attired and carried walking sticks that clearly doubled as weapons.

It wasn’t hard to talking to these kids in Tompkins Square Park because I looked like an older version of them. I struck up a conversation with one of them, a tall blonde, after breakfast. She said she was 17 and claimed her single mother abused her. “She once banged my head up against the refrigerator. She was a very nervous woman,” the girl said, pausing to take a drag on her cigarette. “Eventually she threw me into detention facility upstate and I broke out of there. I came here and got into prostitution,” she went on. “Had to. I had a pimp. But one morning I woke up staring at his gun in my face and I split, coming down here. I have friends here. And I know what to do if I need food or clothes.”

She drifted off, a wraithlike presence in a thin woolen dress and a fur stole that her pimp probably bought her. I took a seat on a park bench, glancing at the Daily Bugle again. There was a story about a “gin mill massacre on Avenue A,” about 50 yards away. I had walked by the tavern earlier, wondering why tables and chairs were overturned when I peered into the windows. The Bugle reported that five people had been killed there in the early morning hours during a drunken melee with knives and guns. New York. Not a nice town. I should fit right in.

A couple of Latino kids raced by, one of them joyously holding aloft a stolen radio like a trophy. There were no uniformed cops patrolling from the 9th precinct five blocks down on East 5th Street. They never bothered me on the street because I blended right in with the denizens of my adopted neighborhood. On this day, I felt secure, maybe because it was a sunny morning and people seemed to accept me here. I gazed at the squirrels climbing up the park trees and hoped the pigeons swooping overhead wouldn’t relieve themselves on my shoulder.

A lanky dark-haired dude in jeans, clean shaven and close to my age, walked by with his rangy black dog who seemed to have some German Shepherd heritage. He sat down on the other end of the park bench and asked if he could look at my newspaper when I was finished with it.

He was polite, even respectful for a change of pace. His dog abruptly began running around the park and frolicking with other canines on the loose. Wordlessly, I passed my copy of the Daily Bugle over to him and noticed he quickly began searching the want ads. A few minutes passed in silence and I asked him. “What kind of work are you looking for?”

“Handy man work,” he said, looking up at me. He had deep set brown eyes and his gaze was not a leer. “I’m pretty good at fixing things. I also do carpentry.”

“Maybe you can try the carpenter’s union,” I said, having once been a union shop steward during my first newspaper job out of college. I looked at his hands. He had long sensitive fingers. He seemed alert and competent. His body wasn’t hard to look at either.

He smiled and said he always had meant to join a union but admitted, “I have problems with authority. I used to fight all time with my father.”

“How come you’re out of work?” I asked him, trying not to sound too much like an aggressive reporter lady.

“To be honest with you, I just recently got out of prison,” my benchmate said. He paused and looked at me evenly again. ‘The charge was assault on 14 police officers.”.

As he spoke, I stared at him in awe and admiration. A street fighting man! “That’s impressive,” I blurted.

“Oh I was drunk at the time,” he said modestly.

We chatted some more and he identified himself as Sean Collins, originally from New Jersey and said he lived a few blocks away in an apartment recently damaged by a kitchen fire. “My wife and son are staying with her parents in Brooklyn while I fix up the place,” he explained, talking like we were neighbors.

Collins withdrew a cigarette from a pack of Lucky Strikes from inside his jacket and offered me one. I declined. I had stopped smoking in California and wouldn’t touch weed for fear I’d get busted in New York. I said as much to this attractive stranger, and told him about getting mugged,. admitting my worries about running out of money. I even joked that I might have to resort to holding up a convenience store. Maybe he’d like to Clyde to my Bonnie?

He chuckled. “You know the old saying, ‘Don’t do the crime if you can’t spare the time.”

It was easy to like Sean Collins and his dog, a friendly fellow named Mistake. I told Collins my new name and my interest in writing a story about runaways in the East Village.

He nodded.

“Except they’re not called runaways these days,” Collins said.”They’re called throwaways and sometimes they go to a social service agency near St. Mark’s Place called The New Way. Check it out. There’s a lawyer there that I see. He’s helping me sue my landlord for the fire.”

Yes, Collins appeared to be a true fighting Irishman and definitely my kind of guy. I had the feeling I’d see him again. Even a married man with a dog couldn’t be all bad.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Back in Phoebe’s quiet shadowy apartment , I put in a call to Jason Slade’s office at around 10 am, identifying myself as a candidate for the freelance opening to his secretary. Amazing how mentioning Sasha’s Freed’s name got her attention so quickly.

“Oh yes,” she said. “ Mizz Freed told us about you, Mizz Ryder. Let’s do this on Friday when the magazine has already gone to bed and things are less crazy around here.” She told me to come to the Bugle at 11 am and we said goodbye like ambassadors.

For a couple of minutes, I paced the living floor shouting “Thank you, Jesus!”and then rushed to Phoebe’s bathroom library, again scanning the pages of the East Village Other and the Village Voice. Both had coverage of the women’s movement in New York: stories about consciousness raising and speakouts on rape and abortion held by groups with names like Redstockings and New York Radical Women, the same groups whose members had organized the1968 feminist protest against the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City. They had attacked the “mindless boob contest” and crowned a live sheep with the title of Miss America. And they had dumped cosmetics, bras and girdles into “a freedom trash can.”

The event drew major media and touched off the women’s liberation movement nationwide but it was old news now and I needed something fresh to interest Jason Slade for my interview with him in two days. I fished out Joy Brennan’s business card from my wallet and called her at a law office on The Avenue of the Americas.

Joy seemed glad to hear from me. She had just come back from a coffee break and was apologetic about her screaming match with Noreen Turette the night before.

“Hope my rants didn’t turn you off our group,” she said. “Usually I don’t get so nasty, but that Noreen is such a phony . She calls herself a ‘feminine feminist” and thinks she’s better looking than Gloria Steinem.”

“She does seem full of herself,” I agreed. “But I really want to know what you’re doing these days. I know you don’t like The Bugle, but—“

Joy made it clear she had just been in a bad mood after tangling with Noreen. “The Bugle isn’t that horrible and you gotta start somewhere when you’re new in the city. By the way, Noreen was right about a couple things. I can’t get a job in publishing. And I can’t get a date either. It’s my weight. I’ve been overdosing on chocolates ever since my mother died two years ago. But you don’t have that problem and a column in the Bugle can get you started in New York. You could be a star.”

No point telling Joy that my goal wasn’t stardom; just a chance to do my work and avoid becoming a bag lady or winding up in prison.

“I’d like to write about your battle with the bulge,” I told her, choosing my words carefully so as not to offend her. “It’s a feminist issue too.”

Joy said she wouldn’t mind so long as I didn’t use her name. And she had story ideas of her own. “I belong to a group called W.O.W.—Women Office Workers. So many of us are sick and tired of being treated like office wives by male bosses. We don’t want to wash out their socks or send lingerie to their mistresses. I can put you in touch with some of our members and they’ll tell you stories about how guys play grab ass in the office. I know one secretary who was sodomized at her desk working late at night. ”

Joy was no friend of free speech, but she was given me a good tip. “Thanks for this,” I said. “Do you think that secretary would agree to being interviewed?”

“Maybe. Look, I can’t talk much longer,” Joy said. “Stay in touch. If you don’t get the column, you can always get a job as a temp. Can you type?

“80 words per minute on good days,” I told her.

“Terrific,” Joy said. “Law firms always like floaters who type fast.”

***

It was a cloudless Friday morning for my interview with Jason Slade. I walked quickly past the druggies and runaways in the East Village, past head shops selling drug paraphernalia and the hippie clothing boutiques touting sex, rock and revolution enroute to East 38th Street and Second Avenue which was 30 short blocks to the Daily Bugle’s midtown building. I had on a thrift shop tweed jacket and black pants and hoped Phoebe’s black beret, similar to what Faye Dunaway wore in “Bonnie and Clyde,” gave me a enough pizazz to pass muster as an intrepid reporter with a top editor.

Inside my shoulder bag were a few writing samples and a resume, but Jason Slade waved those away after he greeted me with a handshake in his small 7th floor office far removed from the bustling city room, explaining that he was interested only in how I would write for The Bugle’s Sunday magazine.

“Sasha Freed told me you’ve written on the women’s liberation movement for both the Los Angeles Press, an underground newspaper, and the Los Angeles Times, a respected broadsheet that appeals to an affluent audience. We’re none of those animals,” he said. “We’re a tabloid that focuses on working class folks in the tri-state area. I’d like the magazine to be a poor man’s New Yorker, but that ain’t easy.”

I guessed Slade to be about 35, a thin man in pale blue shirtsleeves held up with red suspenders. He had prematurely gray hair and bright blue eyes. He spoke in brisk preppy accents that reminded me of an English professor I had at UCLA who lectured on 19th century novelists. A nice man, but why wasn’t a woman in charge of selecting a columnist who would write a feminist issues? It turned out the column was Slade’s idea.

He gestured to a chair opposite his desk, which held a bust of Alfred E. Newman, the Mad Magazine mascot, and the words “What –Me Worry?” At least this editor had a sense of humor, always a good sign. He didn’t waste time on chit chat, making it clear what he wasn’t looking for.

“As you probably know, New York City is on the brink of bankruptcy, there’s a drug epidemic , a high homicide rate and police corruption. I want strong stories in a column that will appeal to contemporary women who are worried about their jobs, their health, their safety and their future. But you would have to walk a fine line. We have a lot of Roman Catholic readers and you don’t want to get involved in an emotional zoo by attacking anti-abortion advocates as “fetus fetishists” as one women’s libber did recently. And nothing on the bra burners or crazies like that woman Valerie Solanes who shot Andy Warhol. Most of the feminist leaders— Betty Frieden, Bella Abzug– have been done to death. So what have you got that’s new?”

When I mentioned the group W.OW. and the travails of secretaries getting hassled by bosses who wanted domestic and sexual services along with typing and shorthand, Slade looked interested. “That could work,” he said. “What else?”

“Well, there could be a feminist protest against Harvey Jewell, the porn King who publishes F.U.,” I said hesitantly. “I’ve heard about a woman writer who may sue him.

Slade perked up considerably. “Oh something on Jewell and the feminists would be great! See what you can get! I mean you might even want to do an investigative piece–maybe get job with him like Gloria Steinem got a job posing as a Bunny at a Playboy Club and then write about it! Our readers would love an expose on F.U.”

For a moment he seemed lost in a fog filled with visions of tabloid scoops for his poor man’s New Yorker, and then abruptly returned to being strictly business.

“Anything else, Ryder?” he asked, using my fake last name if to reassure me he was a man who believed in gender equality.

“There’s a rumor that the FBI has sent undercover agents into the New York offices of NOW, Betty Friedan’s group, looking for female fugitives from the Weather Underground,” I blurted, suddenly desperate to connect with this quirky character. He was beginning to seem like a skinny Santa Claus. But I’d have to be a good girl.

Slade’s eyes gleamed. “A story like that would definitely get attention if you can nail it down,” he said. “What are you working on now?”

“A story about runaways in the East Village,” I said. ‘Some of the girls are getting forced into prostitution and the boys are becoming drug runners. I’m just getting started.”

“A story on the runaways could be a cover for the magazine, so keep at it and try not to get yourself killed,” Slade said. ” In the meantime, send me three sample columns on the women’s libbers and what they’re up to, 750 words each, and we’ll send you a check for for $300 even if we don’t use them. The deadline is next Friday, and you’ll be competing with 10 other applicants. Can you deliver?

I nodded, unable to speak. As he stood up from his swivel desk chair and escorted me to the door, I noticed Slade was wearing snakeskin loafers. I was enchanted and stumbled into the city room on my way to an elevator bank, practically oblivious to the mostly male reporters banging out copy on their typewriters. A stout balding man, apparently the metro editor, chomped on a cigar and suddenly shouted, “Where’s the god damn memo on the god damn fire in Brooklyn?”

For a few brief moments, I felt at home.

#

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.