Photographer Phil Stern Opens His Very Own Gallery In Downtown L.A.

Here’s Phil Stern’s famous picture of Marilyn Monroe, looking scared.

Frank Sinatra lighting JFK’s cigarette

Sinatra’s profile from the rear

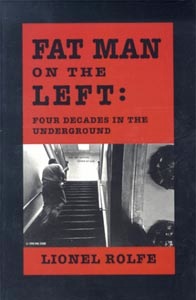

Phil Stern’s photo of Lionel Rolfe from the rear, as used in the book “Fat Man on the Left.” The lettering at the top of the stairs was a bit of Phil Stern fun, way back in those pre-Photoshop days.

By LIONEL ROLFE

The Phil Stern gallery in downtown Los Angeles opened its doors to the general public, a few days later than planned. It’s a small space at 601 S. Los Angeles St., next door to Coles, which claims to be the oldest restaurant in downtown.

The gallery features a collection of photographs of John Kennedy’s inauguration, some of which were in Vanity Fair last month and originally appeared in Life Magazine.

The premiere party for the Phil Stern Gallery was Jan. 20 in a great cavernous room of brick, iron and wood high in the Pacific Electric building where the lighting was perfect, and the crab and salmon hors doeuvres were delicious and the house was packed with mostly beautiful people. Appropriately, it was the 50th anniversary of the inaugural in 1961, the launching of Camelot.

Many of the photos from the premiere will be on the wall of the gallery that just opened, including not only a lot of John Kennedy and the Kennedy clan, but almost all the great musicians and Hollywood stars who attended the gala celebration thrown by JFK and Frank Sinatra as a way of setting the scene for Camelot.

The pictures are incredible not only because Phil Stern is a great photographer, but because Frank Sinatra took him under his wing and got him the inside track. Frank Sinatra dubbed Stern his personal photographer, which got him the ringside seat at Camelot.

Phil Stern has been selling his prints of his photographs for years for thousands of dollars each from his modest home in Hollywood. For example, when Madonna wanted to buy a Phil Stern photograph of Marilyn Monroe, she had to come to his then unkempt tired green-walled box cluttered abode built in the same alleyway where the Keystone cops used to follow each other like lemmings into a lake.

But the truth is only a few of the most dedicated collectors found their way to his home. Most of his business came from New York magazine and book editors and publishers who had long had his number. Most individual collectors purchased prints from the Fahey-Klein gallery, who will keep selling his work.

He doesn’t think they’ll be a conflict between his new gallery and Fahey-Klein.

Phil Stern’s gallery will draw from his newly archived collections on the many subjects he has documented. These exhibits will change from time to time and more, there will be corollary exhibits by other younger photographers whose cause he wants to champion.

Stern has finally gotten to this point in life after spending decades trying to organize his files. Over the years, a number of people had tried to archive his life’s work. Clearly he found some comfort in being surrounded by his photographs unknown by any one but him. He could pull a picture out of a box and talk in great and humorous detail about its story. Long before he became known for his celebrity photos in Life Magazine, he had documented the Great Depression and the Great War of the ’30s and ’40s.

But Donna Lethal a young archivist and author of the forthcoming book, “Milk of Amnesia,” seems to have made progress where nobody else had. She has finally gotten a handle on the giant collection, working with Marc Baker, the gallery’s curator.

Arriving by van, Stern’s son Peter greeted him at the door. Then Peter Stern, Lethal and Baker hovered as Phil Stern walked in with a cane and sat down next to his oxygen tank. He took a few moments to get adjusted, then said nothing for a few moments, and seemed to just look around to get his bearings. After a few more long moments of silence, he dispelled the notion that he didn’t have everything under control. He began by announcing that “everything is wearing on me, including this interview.’

Stern is asked, why a Phil Stern gallery now?

Stern thought for a moment, then said the decision to open the gallery was the result of long conversations between he and Peter.

“This is about my legacy,” he said.

“But you have always said you weren’t an artist. A lot of people now think you are a great artist on the camera.”

“Matisse I ain’t,” he said. Stern doesn’t believe any photographers, including himself, can ever really be called an artist “like say Rembrandt.”

“In my mind a photographer is like a carpenter. He can make a beautiful cabinet and you can exclaim `it’s a work of art,’ but it’s never going to be a Rembrandt,” Stern said.

He then asked his son to get Rupert Murdoch’s The Daily on his iPad. He waited impatiently while the online newspaper loaded. He took a look and snorted with enthusiasm. “My prurient interest is in selling content,” he joked, mostly serious.

He said his best known work is black and white but he has a lot of color shots as well that could be exhibited. A good title for that exhibit might be “Adios Kodachrome,” he said, noting that while the new online newspaper was being launched, Kodak had just announced that it would no longer be manufacturing its iconic film brand. Truely, it was the triumph of the digital over paper and film mediums.

Stern has an almost purposely blue collar way of approaching his world view and perhaps his art, even if he won’t call it such. He broke into photography as a teenager, taking pictures for the old Brooklyn Eagle.

Yet when Life Magazine did an exhibit of the best of its photographs, the lead photo was not a Margaret Bourke-White or an Alfred Eisenstaedt. It was a Phil Stern picture of a tired couple from Oklahoma, trying to cross the border into California in 1939 in their old Ford truck. It was certainly one of the great photographs to come out of the Great Depression. It was 1939 when Stern took the picture for the now long-defunct Friday Magazine. Defeat was written all over their incredible faces. They were well past the point of despair, facing a highly uncertain future. But you knew they would go on, and perhaps even persevere—or perhaps not. This was vintage Phil Stern, the social realist. There was Stern, the lad from Brooklyn, who grew up reading the Yiddish Forward, whose political and spiritual essence was molded by the New Deal and the Depression.

As befits his time, Stern was a political lefty. He had a longtime feisty relationship with John Wayne whose dynamics was based on their political differences. Wayne called Stern a Bolshevik and Stern called him a Neanderthal.

Stern was always a prankster – make of that what you will. One of his favorite pranks was the time when he was in the old Soviet Union and he hunted up the stamp with the biggest, gaudiest picture he could find of Vladimir Lenin, stuck it on a postcard and sent it to his Hollywood pal John Wayne.

An exchange of name calling followed.

Wayne was good enough friends with Stern he allowed Stern to take photographs of him in tight underwear. The clear suggestion showed Wayne exhibiting a high degree of sexual ambivalence in an actor who specialized in playing macho man, and that was the joke of the pictures.

The fact is there is a unique Stern vision that you can say is artistic, or just craftsman like. Either way, it’s a very real vision imbued with hard times and war.

Stern became the official photographer of the Darby’s Rangers. Of the original 1,500 rangers, only 199, one of them Stern, survived. It was Stern who took most of the great combat photos of the North African campaigns of World War II. His photos first appeared in Stars and Stripes. While other photographers waited around headquarters for an assignment to take a picture of a bigwig at an Army event, Stern was on the battlefield. So much so he won a Purple Heart and almost lost his life from his war wounds. There was even a feature movie made of the Darby’s Rangers in which Stern played himself. And, in fact, this is what provided his entree into Hollywood.

It’s been said that Stern made idols out of the ordinary grunt on the battlefield and caught the human side, even the working stiff side, of the greatest of Hollywood’s greats.

He arrived in Hollywood shortly after the war and after a while, became Life Magazine’s man in Hollywood.

The single photo that probably made him the most money was one of James Dean, but another he took of Marilyn Monroe especially told why people paid so much money for his photos. He caught Monroe looking vulnerable and somewhat sad – in no way was it a glamour shot. Instead it was a glimpse into her soul.

Stern also became famous for his photos of James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, John Wayne, Spencer Tracy, and Marlon Brando, among others.

It’s a long way from those two haunted Okie faces to being an official photographer of the 1961 John F. Kennedy inauguration. But it was no accident that along the way, Stern also photographed almost every great jazz musician, because he took all the covers of Pablo Records, a record label owned by jazz impresario Norman Granz. Granz insisted that Stern do all his covers, and because nearly every great jazz musician appeared on Granz’s label, Stern took their pictures.

In Stern’s universe, you see the people behind the celebrity masks. And he was relentless in getting the shot. It was the quality that molded Stern’s photographs and the man himself.

Once, on the New York Street of the Paramount lot, Stern pulled up on his motorbike to shoot a stunt scene. A movie camera had been rigged up to work automatically in a trench over which a stunt driver piloted a pickup truck that was supposed to be several feet off the ground.

So Stern got off his motorbike, picked up his camera, and placed himself squarely in the fox hole with the automated movie camera.

“That was kind of crazy,” someone said to him.

“How else am I going to get the shot,” he said.

Every time Stern took a picture, he was on the battlefield. Death was that intimate a companion to him, which perhaps is why his pictures are also so full of life. Stern was fearless when stalking his photographic prey.

Stern was well into his 70s when he took that shot on the Paramount lot, and now he’s in his 90s, and doesn’t putt around the busy streets of Hollywood on a motorbike any longer. What with age and his need for oxygen, he’s far less mobile than he once was.

His character was, in essence, simple. He was a Brooklyn-born Jewish kid who went to fight the Nazi beast and for him the war never stopped.

Being relentlessly Jewish was a part of who he was. Stern is in no way religious, but it was not accidental that one of the pranks he is proudest of is how he took photographs of famous decidedly very non-Jewish celebrities like Marlon Brando, Alfred Hitchcock, Jimmy Stewart, Bob Hope, Spencer Tracy, John Wayne and Frank Sinatra reading the Forwards, the old Yiddish paper Stern grew up reading.

The first star he asked to hold up the newspaper as if he were reading it was Marlon Brando, who of course didn’t know a word of Yiddish, but was tickled by the idea. James Cagney, who had the map of Ireland written on his face, was another of his models, but the truth was Cagney loved and spoke Yiddish.

For Stern, it was all “theater of the absurd. Theater of the absurd has to be invented by Jews because Jews have the most grist and subject matter, the most pertinent human trauma to supply material for it, because of the nature of their historical predicament.”

Over the years, he has become increasingly grumpy. But people around him don’t seem to mind – even when they are his neighbors, who who help him daily in getting on, they know he is both their grumpy neighbor and a national treasure.