$4 Gas Is Only the Beginning

By Leslie Evans

Republicans and Democrats are scrambling in a blame game over the skyrocketing price of gasoline, which is rapidly approaching the historic highs of the 2008 oil shock. As of April 29 pump prices for regular had topped $4 in thirteen states and crested $3.90 in eleven more. The April 23 Christian Science Monitor carried the headline “Obama faces trouble with $4 gasoline.” The story led off: “Polls show Americans blame Democrats more than Republicans for $4 gasoline prices, and President Obama’s poll numbers show it.”

Of course, Americans traditionally hold incumbents responsible for any bad thing that happens. New Jersey governor James F. Fielder was voted out of office in 1916 as punishment for shark attacks off the Jersey shore. And drought-stricken states throughout the twentieth century voted against incumbent presidents who failed to make rain.

Things aren’t made easier by a Republican and Tea Party establishment that lives on a different planet, where global warming is a hoax, oil is an inexhaustible gift from God to Americans as a reward for their exceptionalism, and all we need to do to put cheap gas in the tank is to “Drill, Baby, Drill!”

Without belaboring the rebuttal here, U.S. oil companies are already sitting on leases on millions of acres of land that they don’t drill because wells are expensive and they have no good reason to think there is oil underneath. After all, more then 1 million wells have been drilled on American soil and in shallow offshore seas. The companies pretty well know what is out there.

And even if we desecrate the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the best informed entity on the subject, in its 2008 report projected that if work began promptly in the nearly year-round ice-bound region it would be ten years before any oil appeared and production could hit 780,000 barrels a day by 2027, declining steadily after that. That is not going to put much of a dent in U.S. daily oil consumption of 21 million barrels a day.

Unhappily, President Obama’s counterpunch has been more symbolic than real. He has called for rescinding tax breaks for oil companies, which are reporting record profits from the run-up in crude prices of the last year. The idea that American oil company profits are the root cause of rising gas prices, though loudly trumpeted by the Democrats and much of the liberal media, is simply not true, and while comparatively big profits may be reprehensible, the notion that cutting them by government action can have any noticeable effect on the price of gas is living in a past that has been gone for forty years.

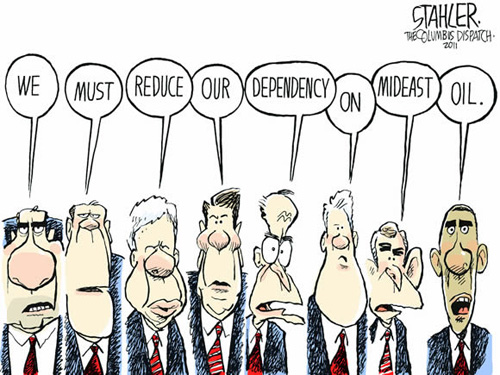

At best you would have to say that all wings of the political establishment are in determined denial. In January the ever-optimistic U.S. Energy Information Administration, which is supposed to know the most about this stuff, predicted that there was only a 10% chance that gas would hit $4 by the end of the summer driving season in September.

Who Owns the Oil? Not Americans

The past that Obama and apparently many Americans seem to be thinking of was the era of the “Seven Sisters,” when privately owned — mostly American — oil companies dominated the global petroleum industry. This lasted from the mid-1940s to the 1970s. The famous seven were the Americans – Standard Oil of New Jersey, Standard Oil of New York (now ExxonMobil), Standard Oil of California, Gulf Oil, and Texaco (now Chevron) – joined by two from other countries, Royal Dutch Shell, and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now BP). In 1973 the Seven Sisters controlled 85% of the world’s petroleum reserves.

Today the six largest privately owned oil companies are BP (United Kingdom), Royal Dutch Shell (Netherlands and UK), Total S.A. (France), and only three American corporations: Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and ExxonMobil. The six together control only 6% of world oil and gas reserves. The balance has shifted overwhelmingly to foreign, state-owned companies. State owned companies control 77% of world reserves, led by Aramco of Saudi Arabia, which was pumping 8.2 million barrels a day (mbd) in 2010 with a claimed capacity of 12.5 mbd, followed by National Iran at 3.5 mbd, Petroleos Mexicanos (2.9), Iraq National Oil (2.5), Petro China (2.3), Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. (2.3), Kuwait Oil Co. (2.3), and Petroleos de Venezuela (2.2). ExxonMobil is the only publicly traded company that even makes the top ten, at 2.5 mbd. Other significant players include Russia and Nigeria. (Forbes, July 9, 2010)

Clearly the U.S. oil companies have only extremely marginal ability to affect the price of oil or gas, and no tinkering with their tax status is going to change that. This is another measure of the relative decline of the United States as a world power, also testified to by the long series of lost, stalemated, or indecisive wars of the last generation.

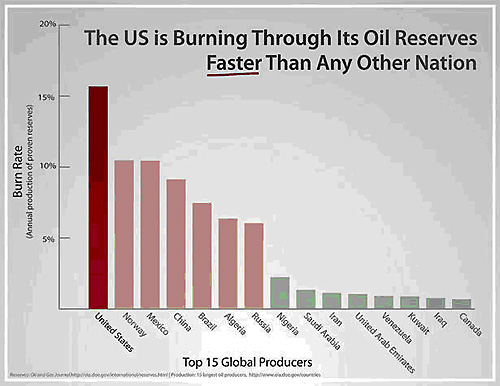

So when we come in for a reality check we find that the United States produces and has reserves of only about 2% of world oil. That tail is not going to wag the dog of world fossil fuel prices. It consumes 25% of world output, about half from imports. It makes up the difference by pumping out its existing supplies at a far greater rate than any other major oil producer, for which future generations will pay the price.

Supply, Demand, and Peak Oil

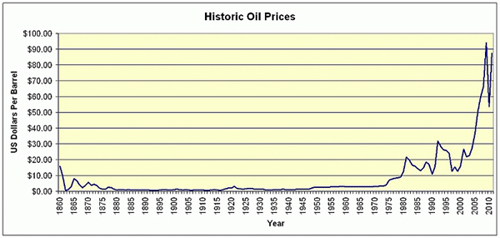

Gas prices in turn depend on the price of crude oil, and that has been rising rapidly. Crude oil sold for about $3 a barrel for some 65 years, from 1880 through 1945. It rose marginally to about $5 a barrel for the next thirty years, until the OPEC oil embargo of 1973, when it began to spiral upward. It hit $21 a barrel in 1981, then roller-coasted down to $10 in 1990, followed by another spike, to a little over $30 a barrel that year following Saddam Hussain’s invasion of Kuwait and the outbreak of the First Gulf War, only to turn downward again a few years later. What is striking, however, is that each trough is higher than the last time and each peak sets a new record.

The present huge upward curve began in 2000. It topped out in 2008 when crude oil briefly hit $147 a barrel, probably contributing as much to the U.S. and world financial collapse as the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

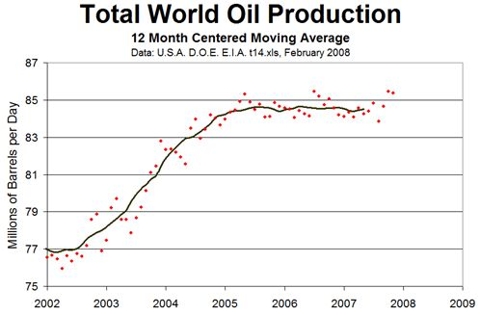

What has happened is that world demand has risen faster than supply. Worse yet, global output plateaued in 2005. Wikipedia summarizes: “Worldwide oil production, including oil from oil sands, reached an all-time high of 73,720,000 barrels per day in 2005. By 2009, production had declined to 72,260,000 barrels per day.” This defies the standard economic model that big increases in sale prices will bring more product to market. Can’t do it if it ain’t there.

The cause is the once-controversial phenomenon called peak oil. It was first proposed by Shell oil geologist M. King Hubbert in a 1956 paper. Hubbert discovered that output from any given oil well followed a bell shaped curve: rising to its highest point when about half of the total oil had been extracted, and declining steadily thereafter, with a substantial portion of the second half unrecoverable. Further, the first half of the output was the easy part, with the second half deeper, more difficult to recover, and more expensive.

Eventually on the downhill side you hit the Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI) limit. Simple crude oil out of a fresh well gives you about 100 to 1 return. That is, it took only the equivalent energy of one barrel of oil to harvest 100 barrels. That has dropped in the U.S. today to one barrel invested to harvest only three barrels of return. Small wonder that the cost of oil has gone up. But at some point on each oil well, even when there remains a large amount of oil in the ground, EROEI falls to one for one. That is the point at which efforts to get the last part of the oil stop. It is why most figures on so-called oil reserves are grossly misleading, as they are to some degree guesses to begin with, and at best include the large percentage of unrecoverable oil ruled out by the prohibitive energy costs that would be needed to extract the product.

Hubbert in 1956 predicted that U.S. domestic oil production would peak between the late 1960s and early 1970s. That is exactly what happened, with U.S. output going into irreversible decline, leading to the U.S. going from self-sufficiency in oil to dependency on imports, particularly from the Middle East. Production in the continental 48 states peaked in 1970. Alaska’s famous Prudhoe Bay wells peaked in 1989. And production in the shallow parts of the Gulf of Mexico peaked in 1998.

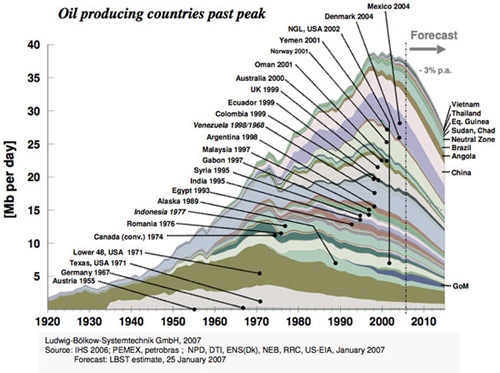

But Hubbert’s curve works not just for a single well or country but globally. And more and more official sources have concluded that global oil peaked in 2005. Below is a graph showing the dates when 24 oil producing countries peaked and went into decline. The graph is from the beginning of 2007. The process has continued unabated since, with Saudi Arabia essentially the only significant oil producer with a fairly persuasive claim to have any available excess capacity, and that is not much on a global scale, amounting to a claimed 4 mbd. The Saudis promised at the beginning of the Libyan revolution to increase their output to cover the loss of about 2 mbd from Libya, but they have actually been able to produce only about half of that.

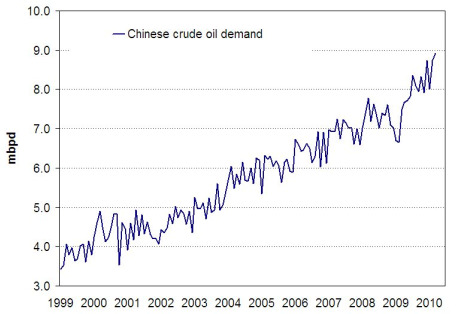

The other side of the coin is the rapid rise in world demand on an engine that is stuck in neutral. There have been slight declines in use in Western Europe and the U.S. through conservation and efficiency improvements. But demand growth has simply shifted to the developing world. China alone increased its daily oil use from 3.5 mbd in 1999 to 9 mbd in 2010, this alone more than eclipses the whole of Saudi Arabia’s claimed excess capacity.

Unwillingness to Recognize That Resources Are Finite

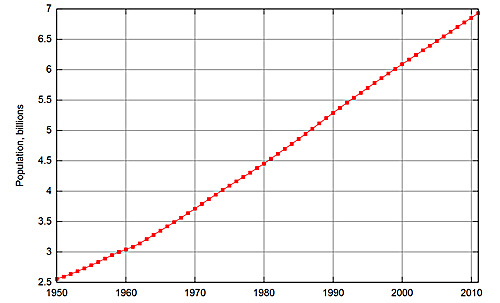

While fossil fuels are finite — the decayed remains of prehistoric plant materials that took millions of years to turn into oil — human population has been growing at exponential speed, from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 7 billion in 2010. Add industrial development and a rise in living standards to that, and world demand for fossil fuels has been increasing dramatically while production has stagnated. In most producing countries it has in fact declined, often by very large margins.

For understandable reasons politicians of any stripe do not want to be the bearers of vastly bad news. Denial becomes an obligatory part of the profession. And that is what we have gotten. While officialdom mostly avert their eyes, there has been a small coterie of whistle blowers who have been trying to wake the country up. They tend to refer to themselves as the peak oil community. These include James Howard Kunstler, whose “ The Long Emergency ” lays out one of the most pessimistic scenarios, where oil decline and astronomical price increases shatter modern civilization altogether and we return to the life of the nineteenth or even eighteenth century, with vast loss of life along the way as modern agriculture collapses due to prohibitive costs of transportation and oil-based fertilizers.

Other figures include the prolific Richard Heinberg, where you might look at his “ Peak Everything: Waking Up to the Century of Declines ” or his large and comprehensive volume coedited with Daniel Lerch, “ The Post Carbon Reader: Managing the 21st Century’s Sustainability Crises .” Along similar lines is “ The Ecotechnic Future: Envisioning a Post Peak World ” by John Michael Greer. Then, among the least apocalyptic of this school, there is Jeff Rubin’s “ Why Your World Is About to Get a Whole Lot Smaller .” Rubin limits his prediction to the collapse of globalization and most air travel due to high fuel costs, leading on the positive side to a revival of American manufacturing industry. For ongoing current news one of the best sources is the Energy Bulletin website of the Post Carbon Institute.

Remember as you read in this literature that no one is talking about oil running out. It doesn’t have to do that to become too hard to get and too expensive for the uses we have built our civilization on, particularly cheap car and truck transport.

To be frank, pioneers are sometimes outsiders who champion several fringe ideas at once. Kunstler warned repeatedly that the Y2K computer clock threat would crash the world economy, and he was a vitriolic critic of suburban sprawl on esthetic grounds long before he had the idea that gas prices would turn the hated suburbs into wastelands.

Richard Heinberg was a personal assistant to the famous crank Immanuel Velikovsky, who wrote numerous books trying to prove that catastrophes described in the Bible such as Noah’s flood were real and were caused by drastic changes in the orbits of other planets in the solar system — in living human memory. Heinberg is also a 9-11 Truther.

John Michael Greer, who writes admirably clear and factual books on fossil fuel depletion, leads another life as a self-proclaimed Arch Druid, where he has a long beard, dresses in ankle length white robes, and writes books claiming that magic and magical beings are real.

Happily Jeff Rubin has more plausible credentials, having served for twenty years as Chief Economist for CIBC World Markets, the investment banking subsidiary of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce.

Heinberg’s “Post Carbon Reader” presents contributions by 36 authors, many of whom are tenured professors or the heads of established nonprofit agencies, above any suspicion of bizarre agendas.

If some of our path breakers have something a bit kooky about them, in the last year a number of long-reluctant official agencies have begun to confirm the peak oil community’s worst fears. Â One of the first was the U.S. military. The UK “Guardian” reported April 11, 2010:

“The US military has warned that surplus oil production capacity could disappear within two years and there could be serious shortages by 2015 with a significant economic and political impact. The energy crisis outlined in a Joint Operating Environment report from the US Joint Forces Command, comes as the price of petrol in Britain reaches record levels and the cost of crude is predicted to soon top $100 a barrel.

“‘By 2012, surplus oil production capacity could entirely disappear, and as early as 2015, the shortfall in output could reach nearly 10 million barrels per day,’ says the report, which has a foreword by a senior commander, General James N. Mattis.”

Most notable has been the turnabout by the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Paris-based intergovernmental advisory body for the OECD countries. The IEA had long been accused of doctoring its figures under pressure from the United States to present an unreasonably optimistic picture. Then, in November 2010, in its World Economic Outlook, it dropped a bomb, predicting that “Crude oil output reaches an undulating plateau of around 68-69 mb/d by 2020, but never regains its all-time peak of 70 mb/d reached in 2006.” Whoa! after years of denying there would be any supply problem for crude for decades to come, the IEA now announces that world crude production peaked back in 2006, with a total output that would never be reached again!

The IEA tried to soften the blow with projections that the shortfall would be made up by gas liquids, tar sands, and other unconventional (and very expensive) sources, claims that were widely regarded as improbable. It capped its peering into the future with a prediction that crude oil would reach $113 a barrel — in 2035! On April 27, 2011, Brent crude was selling for $125, twenty-four years ahead of schedule and already $12 over budget.

NOTE: There are two international standards for oil prices. The conventional one for the United States is West Texas Intermediate (WTI), set at oil storage depots in Cushing, Oklahoma. This is the amount usually cited in the American media for current oil prices. The other, European, price, based on the UK’s North Sea wells, is called Brent crude (for a well named for the Brent Goose). Normally the spread between the two is about 75 cents, but in the last year it has grown to more than $10. It is widely accepted that the WTI price (on April 27 at $112) is artificially low due to limited storage in Cushing, which is overfilled. Large parts of the U.S. pay the Brent price, not the WTI price, including the Gulf of Mexico states and the West Coast.

The unraveling by one-time peak oil skeptics has continued. Ronald Stoeferle of the Erste Group, the leading financial provider in the Eastern European Union with more than 50,000 employees, reported on March 14 on oilprice.com that “the British Department of Energy and Climate Change is collaborating with the Ministry of Defence and the Bank of England on a study about the consequences of peak oil.” He added that “peak oil is not just a chimera of doomsday prophets, scaremongers, and congenital pessimists, but rather imminent reality,” citing a report that 64 countries “have already reached their maximum production levels.”

Stoeferle then cites a recent study by a German government think tank warning of the risk of a “tipping point” in which “the economic system would tip over.” He summarizes the risks the German government study considers possible:

-The Western industrialised powers lose their influence

– Dramatic shifts of political and economic balances of power

– Massive reduction of mobility

– Further erosion of trust in governmental institutions and politics

– Negative impact on democracy, since a systemic crisis would create “space for ideological and extremist alternatives to existing forms of government”

– Possible partial or full failure of the markets, which could result in a regression to barter trade

– Shortages in the supply of essentially important goods, such as food, and famine as a result

– Price shocks in practically all areas of the industry and in almost all stages of the value chain

– Banks would lose their basis of business, since companies with low creditworthiness would not survive

– Loss of confidence in currencies, as a result hyperinflation, and return to barter trade on local level

– Mass unemployment and state bankruptcies

This vision is hardly less apocalyptic than the most pessimistic scenarios of James Howard Kunstler and Richard Heinberg.

Retired CIA analyst Tom Whipple, who has specialized in the study of peak oil since 1999, looked at the future in his February 17, 2011, column in the Falls Church News-Press (Falls Church, Virginia):

“With declining quantities of fossil fuels, and the likelihood that renewable forms of energy cannot be developed and expanded quickly enough, continued worldwide economic growth is unlikely. While countries that are self-sufficient in fossil fuels and those able to get a lock on a share of fossil fuel production (most likely the Chinese) will be able to grow for a while. Eventually, however, they are certain to encounter other constraints. At the minute fresh water and food seem poised to follow fossil fuels into scarcity, but there are many other natural resources that soon will be too expensive for common use.

“Taken together, the decline and eventual near cessation of fossil fuel production and that of many other minerals, disruption in global weather patterns, and the growing food and water scarcity will constitute the third great transition [the first being agriculture, the second the Industrial Revolution]. Unlike the previous transitions in which life arguably got better for some, if not most, of the world’s peoples, any upside to this transition seems to pale in the face of what is to come. Obviously the seven billion of us are going to have to shrink to some more sustainable number. Some demographers are already arguing that this might be under 1 billion.”

Small wonder that virtually every prominent politician sees leveling with the public on this one as a career ender.

What Can Be Done?

It’s when you start to think about what can be done that you really get why the politicians won’t touch this one but just keep hoping the worst will hold off until they are out of office, or better yet, have made it to the end of their lives ahead of the storm. It is true that, while the storm looks to be beginning right here and now, there is always some chance that the decline will be put off for a while, and the downward slide will be slow. But the end is pretty clear and even an optimist is not likely to plan for it being more than a century away. World population, heavily dependent on fossil fuels for transportation, heating, electricity, and food production, is climbing toward an estimated 9 billion. Arable land is being eroded, global warming is already disrupting harvests, water tables, many of irreplaceable one-time deposits of “fossil” water, are being over pumped, and the price of oil keeps climbing.

Even uranium, if we were to choose to go the nuclear route after Fukushima, is within decades of exhaustion. And so far only oil — and liquified natural gas at steep costs — can be pumped into a gas tank. Solar and wind power have extremely low return on energy invested, depend on oil to manufacture and transport the equipment, and are not going to run any airplanes or ocean going cargo ships.

There are things that can be done, so long as there remains a substantial amount of oil available. These are mostly fossil fuel extenders rather than true replacements. But they are steps that should be taken, in fact should have been taken thirty years ago. One step would be to build or re-build a nationwide system of electric railways and street cars. Electricity can be and is generated in large quantities by natural gas and, with its ecological overhead, by coal. Both of these are finite as well, and probably have less than a century to go, but they will be around for a while after the oil has become too expensive for ordinary passenger cars and many other of its customary uses.

America needs to begin replacing, or at least supplementing on a large scale, the agribusiness model of food production. Organic farming, apart from its health claims, has the great virtue that it does not depend on fertilizers made with fossil fuels (mainly natural gas). As oil becomes more expensive and more restricted in its allowable uses America will need to reverse the flight from the land that was one of the major demographic transitions of the twentieth century. Today’s economy in which a huge portion of the population do not produce any tangible product is possible only because of the expenditure of the huge equivalents of human energy stored in finite, one-time deposits of fossil fuels. As these tangibly decline, standards of living will decline as well, and a far larger proportion of the population will have to be committed to the production of food and physical commodities.

Living space will also have to be redesigned. The incomprehensibly large investment in automobile-enabled urban sprawl with its concomitant long commutes in private automobiles of the post World War II period will prove to be too expensive to maintain. Higher density city and small town cores will become the new norm, with much of the abandoned suburbs being returned to the farmland they had concreted over. Urban front and back yards will be dedicated to raising food in the pattern of the Victory Gardens of the last world war.

One dead end that unfortunately has been endorsed by the Obama administration is ethanol. Declining arable land, droughts and fires, and the rising cost of fertilizer are causing rising food prices, already putting the very survival of a large part of the world’s population at the mercy of a single bad global harvest. Diverting corn and sugar from the food supplies of poor nations to fill the gas tanks of rich ones is an unconscionable act.

Every U.S. president since Nixon has pledged to wean the country from dependency on foreign oil. So far this has been mostly just talk. A formidable obstacle to ending the paralysis in U.S. energy policy is the continually reinforced evidence of the solidity of our civilization. Like the citizens of Eternal Rome, it seems so established, so predictable, so real as to be unshakable. Surely it will go on, if not forever, than at least for our lifetimes, even for those of us who are pretty young. A good antidote to that kind of mesmerizing thought process is Jared Diamond’s 2005 book “Collapse.” He traces the unanticipated and unexpected collapse of several mostly small ancient societies. The Polynesian inhabitants of Easter Island, having come from the Western Pacific where a more lush growing season saw palm trees growing faster than people harvested them, got in the habit of chopping down the trees in their new home at the same rate, for firewood, for building materials, and to make ocean going canoes. Over time the more barren Easter Island couldn’t keep up. There were fewer and fewer palm trees. When the last tree was cut and there was no wood to make ocean going canoes for fishing the population collapsed to a tiny handful of survivors. What do you suppose the Easter islander was thinking when they cut down the last tree, or the next to last one?